After, when the sea will curl violently

They will say: “it is the fatal conscience of that girl,

She had many sins because she always lived in verse

And what you do on earth, on earth you pay for.”

—From “After,” by Julia de Burgos

In 1928, when Julia de Burgos was fourteen, Hurricane San Felipe devastated Puerto Rico. The Category Five storm left not a single building unscathed, least of all the wood casita in a mountain barrio in Carolina where De Burgos was born. Three hundred people died in what would be, for the next ninety years, the most violent storm in the island’s history. Julia de Burgos did not record her experience.

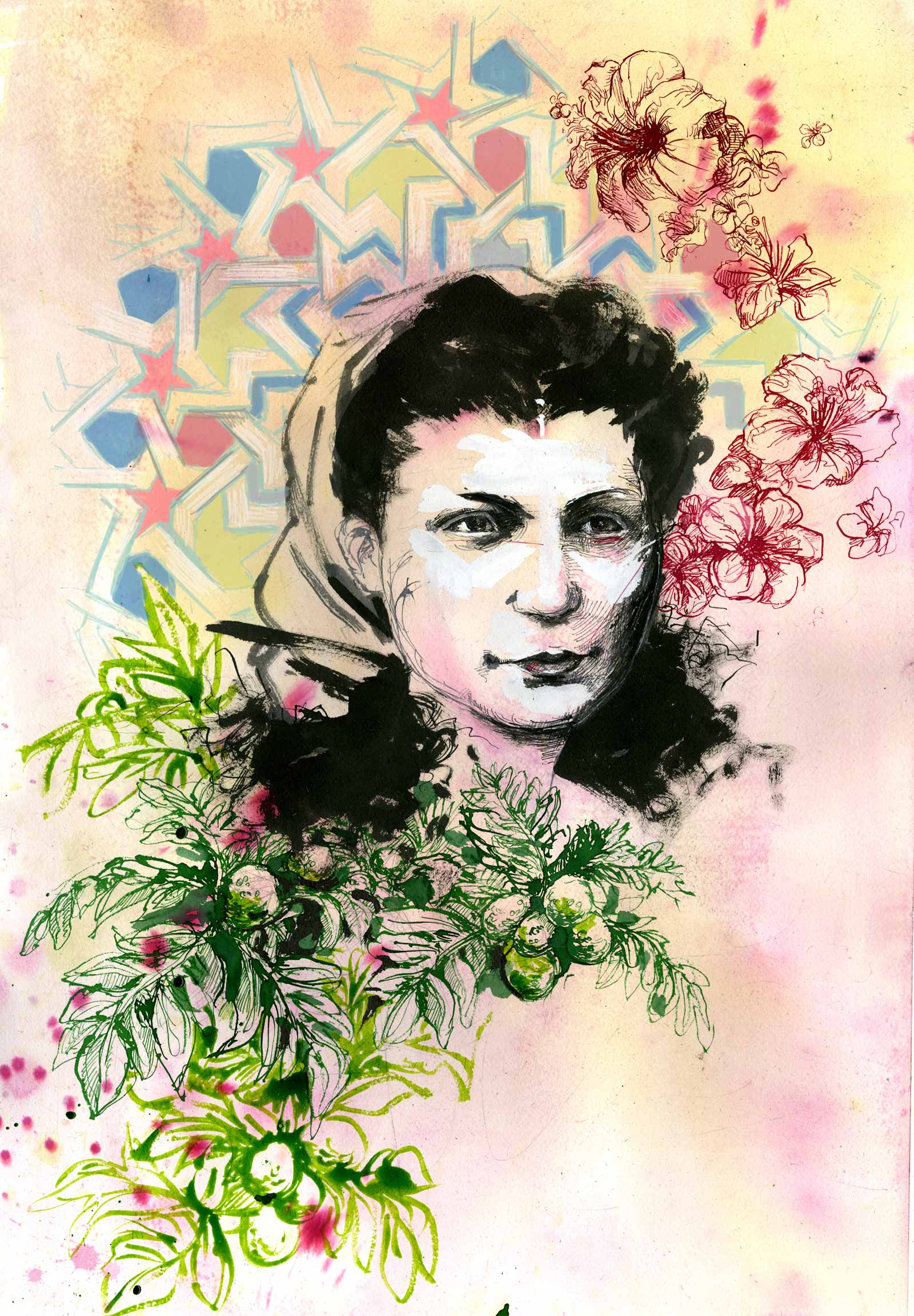

Puerto Rico’s most famous poet and greatest literary figure, De Burgos is as significant a cultural icon for the island commonwealth as the artist Frida Kahlo is for Mexico. Every line of De Burgos’s verse is imbued with passion, feminist self-assertion, and love of homeland. As with many female artists, De Burgos’s life story added to her legend, though her romantic life and untimely death threatened to overshadow her work by turning her into an allegorical figure for the patria’s humiliations. Yet, outside of Puerto Rican communities, she is largely unknown despite the fact that her poetry, while firmly rooted in place, addresses the universal human subjects of love, war, and self-creation.

De Burgos’s life spanned Puerto Rico’s full entrenchment as a colony of the United States, while her public life as a writer took place against the backdrop of the twentieth-century’s global conflict between fascism and democracy. The problems Puerto Ricans face today, as their impoverished island fights for survival in an era when the international order seems to be coming apart, are the legacy of the struggles De Burgos faced. In January, I traveled to Puerto Rico with my father, carrying a copy of Julia de Burgos’s letters, visiting the places she had lived, trying to hear her voice.

*

I am a child grown piling rubble

of stolen innocences,

a bloodied child furling screams

with all the tatters of my hills.

—From “Countryside 2”

The central square of Carolina, Julia de Burgos’s hometown, is empty. Over 250,000 people have left the island since Hurricane Maria hit last fall, driven out by poverty and lack of electricity, to sleep in FEMA-funded hotel rooms and to work far from home in places like poultry-processing plants in South Dakota. Their departure recalls the mass migration to the US, spurred by the Depression, that occurred in De Burgos’s generation.

“Julia is one of the premier figures of literature, and she surpasses the borders of Puerto Rico,” said Irma Santiago Torres, director of the town’s archives, whose antechamber boasts two giant paintings of De Burgos. I leafed through laminated copies of the letters Julia wrote to her sister, Consuelo Burgos, who was a lawyer and Communist organizer. The archive’s binders were thick with announcements of honors, conferences, and centenaries for De Burgos. February 17 (her birthday) is Julia de Burgos Day in Carolina. Her likeness has appeared on a postage stamp and in a mural by Yasmin Hernandez. In Puerto Rico and the US, her name adorns two parks, six monuments, seven buildings, five schools, a shelter for battered women, and an arts center in East Harlem’s El Barrio, opposite a wall showcasing a mosaic of her face. During her final days, De Burgos wrote to her sister: “It honors and satisfies me that while the government of this country repudiates me for struggling for the welfare of humanity, including its own people, my Puerto Rican gente honor and protect me, materially and spiritually.”

In 1914, the year of Julia’s birth, the area around Carolina was sugar cane country. Charles Allen, Puerto Rico’s first US-appointed civilian governor, had spent his career after politics ruthlessly advancing the interests of the American Sugar Refining Company until it had swelled to become the largest such in the world. On the island, his political appointees showered the company in tax breaks and land, transforming Puerto Rico’s existing system of land tenure, in which individuals owned diverse small farms, into a US-dominated monoculture. Carolina’s current suburban sprawl conceals the town’s history of violent labor strikes by machete-wielding cane-cutters, which earned it the nickname El Pueblo de los Tumba Brazos, or Arm Hackers’ Town.

De Burgos was born into a family so poor that disease and malnutrition killed six of her siblings. Yet she grew up reading Don Quixote and Kierkegaard, and began writing verse while still a child. Her father, Francisco Burgos Hans, worked at odd jobs, while her mother, Paula García, cultivated their tiny parcela. Paula was half African, a heritage Julia defiantly celebrated. No image of Paula García survives. Vanessa Pérez Rosario, author of Becoming Julia de Burgos, told me that her sole photo may have been lost in the devastation of San Felipe.

Advertisement

Julia’s country childhood gave her two things: an affinity for Communism and a connection to Nature, which became her chief muse. During the illness of her final years, it was to Puerto Rico she longed to return:

All the flowers… are open, awaiting my arrival, and they clothe beaches of the most beautiful blue, to receive my life, whole and healthy like before. I want to spend days by the sea, burning myself in the sun like we did in our juvenile days, and to be able to return and see my river, with the same tranquil and yearning eyes as I did when I was its bride.

Fat hunger cuts the dreams

of emaciated creatures

who did not know how to die

when they stumbled on their cradle.

—From “From the Martin Peña Bridge”

In 1927, Pérez Rosario told me, Julia de Burgos moved, unaccompanied, to live with a wealthier family in Río Piedras, though the details of this arrangement are not known. Unlike the elite literary ladies whom she later encountered, she would not have been expected to receive an education. “Women of her social class did not go to high school, nor college,” said Pérez Rosario, and yet, De Burgos did. A photo in Carmen Lucca’s Julia’s Diary and Other Simple Truths shows her leaping over a hurdle during gym class. The photo brings to mind Julia’s lines, from “To Julia de Burgos”: “the wind curls my hair, the sun paints me.” After graduating, she signed up in 1931 for a two-year teaching certificate course at the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras.

Would such a route to self-improvement still exist for the Julias of today? In 2017, Puerto Rico’s fiscal oversight board announced $300 million in cuts to the University of Puerto Rico’s budget; the announcement was followed by a two-month-long student strike. Julia Keleher, the US-born head of Puerto Rico’s Department of Education, currently plans to close nearly three hundred schools, nearly a third of those in Puerto Rico, as well as to introduce charter schools to the island. In Maria’s aftermath, public schools, lacking power, stayed shut until parents in several towns took over the buildings themselves. On March 5, teachers from Naranjito, the mountain barrio where De Burgos herself had worked as a teacher, marched against these closures.

Río Piedras is far emptier than it was in De Burgos’s day. When I visited, Paseo de Diego, a once bustling shopping street, was mostly vacant, showing the effects of a decline that began in 1996, when a gas-line explosion destroyed a six-story building in the town center, killing thirty-three people and wounding sixty-nine others. Río Piedras’s graffiti provide a visual lexicon of rebellion: portraits of Puerto Rico’s indigenous Taíno people, long-imprisoned independence fighter Oscar López Rivera, guns and pigs gorging on dollars. Beside these murals, drug addicts lounged, cats scampered, and lush gardens veiled Puerto Rican houses constructed with pleasure-loving brio—their Doric columns fatter than Classical rules would allow, their rejas (iron bars fixed over windows) wrought into exuberant starbursts. The beauty of these dwellings is distinctly un-American. In the US, urban planners would condemn these houses as too sensuous for the working-class people who inhabit them, and contemporary architects would sneer at their builders’ embarrassing delight in ornamentation.

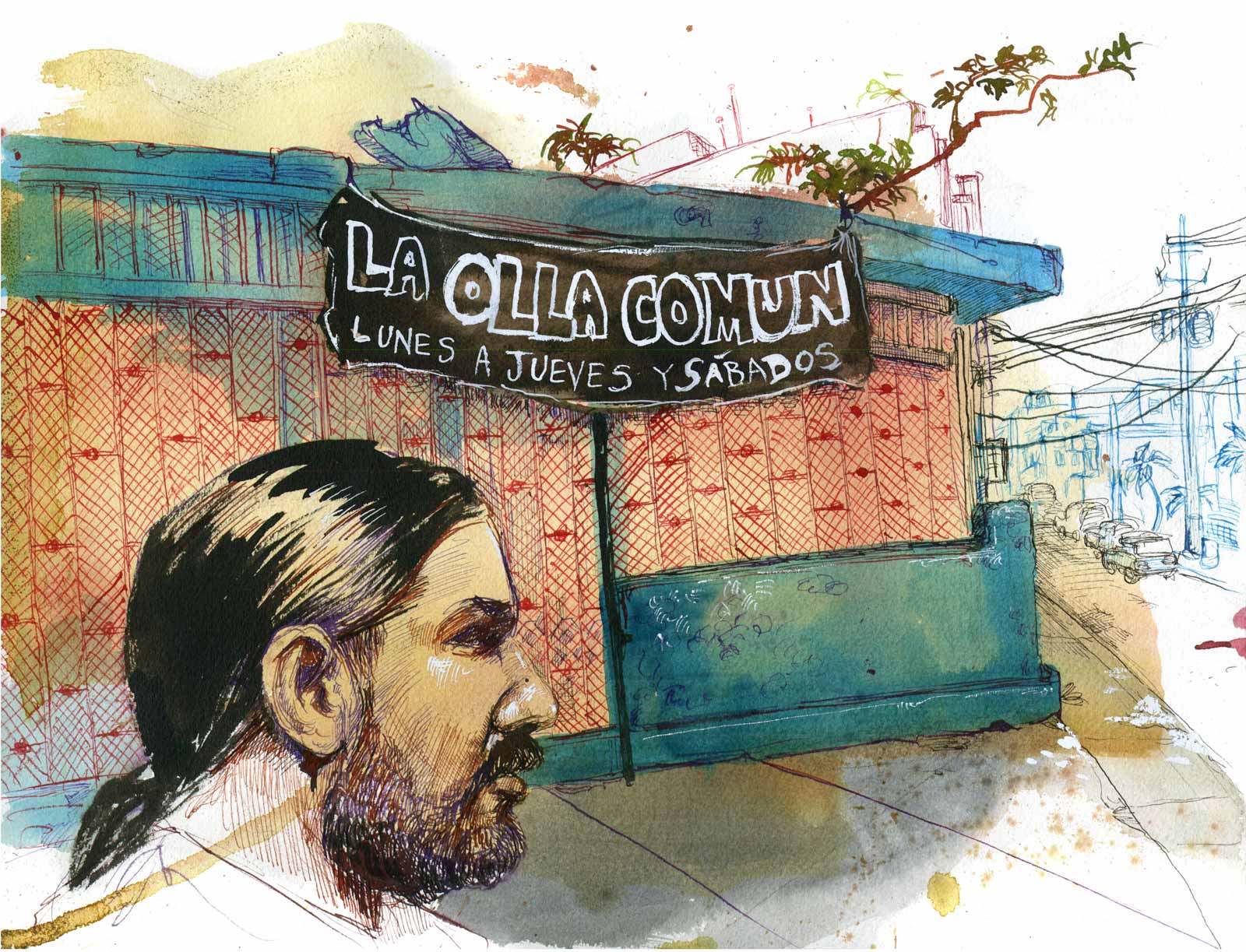

In a neighborhood bookstore, Librería Mágica, shelves sagged beneath the weight of books by Puerto Rican authors unknown outside the island: great castles of words written in Spanish that exist here alone, their colonial writers cut off from the supply chains that would get them into the bookstores of Mexico City or Madrid, but kept, by their use of Spanish, from widespread distribution on the US mainland. A few blocks farther is La Olla Común, the mutual aid center, one node of a network that sprang to life after Maria, in the vacuum created by the local government’s incompetence and the federal government’s negligence. Months after Maria, as many as sixty people still lined up for a free breakfast every weekday morning, brought there less by the hurricane than by the slow-rolling economic disaster that preceded it.

“The people who work in the mutual aid centers lost their jobs, their houses,” said Scott Barbés, a labor organizer who worked at La Olla Común. “Their families left, but they decided to stay and fight.” Like many Puerto Rican activists, he came to see Maria as an opportunity. The word “colonialism” reentered daily vocabulary. In the mutual aid centers, Puerto Ricans could practice a prefigurative politics of independence—handle their own affairs, build power, and rid themselves of the self-contempt that their colonial status had fostered in them.

Advertisement

Back in 1930, University of Puerto Rico students found a political vehicle for such aspirations in the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, and De Burgos became the secretary general of its sister organization, the Daughters of Freedom. The party’s president, Pedro Albizu Campos, was a brilliant Harvard-educated lawyer, deeply influenced by Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising, who returned to Puerto Rico intent on freeing the island from American sugar trusts and colonial rule. A devout Catholic, Albizu infused nationalism with an uncompromising commitment to armed resistance, martyrdom, and sacrifice. “Conqueror of prisons, liberator of courses, perpetual burier of all chains,” De Burgos hailed Albizu in a poem; and when the young nationalist Rafael Suárez Díaz fell to his death during clashes in the San Juan capitol building, De Burgos eulogized him. “Your immaculate offering is the first wick / that will ignite the bonfire of the revolution.” Though an atheist, De Burgos sounded Christian only when she wrote about politics.

After graduation, De Burgos worked a series of jobs. The closest she ever had to a résumé was a list of employment references she supplied to the FBI, when she was interrogated as a suspected nationalist and Communist. (Her sister Consuelo, called to a hearing of the House of Un-American Activities Committee, refused to recognize its jurisdiction.) But De Burgos’s list for the FBI gives dates that contradict other evidence; it may be best understood as an attempt to fit a poet’s fluid life into the government bureaucracy’s rigid expectations. After my father and I left Río Piedras, we followed the list to the site of her first job, in Ponce, Puerto Rico’s second-largest city.

The sea sometimes ascends the gravestone of the hills.

There it is green sky, as if wanting to rise to my hands.

—From “Presence of Love on the Island”

Ponceños have a saying. “In Puerto Rico, there is Ponce. The rest is parking.” It is a seigniorial city, whose pastel architecture brings to mind the macaron parlor of Marie Antoinette’s hallucinations. Layer cakes of filigreed stucco, with walls painted like cotton candy and sky. Here, in 1933, De Burgos managed a milk station for the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRRA). President Roosevelt had established this New Deal era agency, along with the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration (PRERA), to address the rampant poverty the Depression had inflicted on the island. The unemployment rate had ballooned to 60 percent, and Albizu was leading strikes against the American trusts that owned the railways, the electricity utilities, and the cane fields. The Roosevelt administration hoped the PRRA would inoculate workers against nationalism, but many in Washington criticized the agency as a socialist-inspired handout.

While it was more Keynesian than socialist, the PRRA was markedly different from today’s PROMESA, the US program meant to address Puerto Rico’s economic crisis. The PRRA electrified the Puerto Rican countryside—which now languishes in the dark. The PRRA attempted to reduce the power of colonial interests in the economy and break the US control of the sugar industry, while, under PROMESA, public assets will be sold off to private, non-Puerto Rican interests. The PRRA employed 60,000 people, while PROMESA plans to lay off large numbers of state employees. The PRRA was a welfare-state cash infusion; PROMESA is bringing crippling austerity measures.

Ponce seems almost deserted now, a casualty as much of failed economic policies as storm damage, its beauty rotting from abandonment—like a Caribbean Venice before the charter tours started coming. When I walked around taking notes, two old men stopped me, to ask if I was scoping the place out for real-estate developers—he meant the vultures who would displace them. The first man, a Vietnam veteran, scoffed that America would let him die for the country, but not allow him to vote for its president. The other man was the nephew of Filiberto Ojeda Ríos.

Ojeda was the commander in chief of Los Macheteros, an armed group that has fought since 1976 for Puerto Rican independence by methods that include bank robberies and attacks on the US military. In 2005, the FBI surrounded Ojeda’s home in Hormigueros and threw a flash-bang grenade through his door. Puerto Rico’s Commission for Civil Rights called for an investigation; Ojeda’s wife claimed the FBI had fired the first shots. In the shootout that followed, the FBI pumped Ojeda’s home with bullets and left the seventy-year-old to bleed out while agents cordoned off the building.

Ojeda’s nephew reminisced to my father about a July afternoon three decades ago when their family picnic was interrupted by police vans, heading to a mountain called Cerro Maravilla. A police informant had lured two young nationalists up to the mountaintop, with a plan to set fire to the communication towers there as an act of protest. It was an ambush. On the mountainside, five police officers executed the men while they were kneeling. One of the two was the son of Puerto Rico’s great novelist Pedro Juan Soto. The Macheteros drew inspiration for their armed resistance from this massacre.

Though every Puerto Rican kid learns about Julia de Burgos in school, the stories of her fellow nationalists are kept out of the classroom. “Children are ignorant,” Ojeda’s nephew said. “You need to fight for the patria. In this moment, after Maria, we can wake up.”

Río Grande de Loíza!… Blue. Brown. Red.

Blue mirror, fallen piece of blue sky

naked white flesh that turns black

each time the night enters your bed;

—From “Río Grande de Loiza”

After the spell in Ponce, Julia de Burgos worked as a schoolteacher in rural Puerto Rican towns: Salinas on the coast, Comerío, and Naranjito in the mountains. The US Department of Education designated a scant three hours a day for Puerto Rican education; the remaining time was devoted to preparing boys for the cane fields and girls for the garment factories. The rooms were spartan, the children boisterous. De Burgos described her teaching philosophy thus:

Carry yourself seriously but speak with a sweet voice. Humiliate no one, since, as you know, adolescence is characterized by unbridled self-love, and when a teacher shines light on the good qualities of a child, it does much more than focusing on their vices.

After Maria, I saw artists doing work in the same sorts of mountain barrios: Lizaimi Rivera Rivera, a circus performer, who hauled supplies up to Comerio each Thursday with the community group Coco de Oro; Chemi Rosado-Seijo, whom I met in Naranjito’s Barrio Cerro, where he had been an unofficial artist in residence since 2002; and his colleague Rebekah, a punk musician and veteran of student protests and occupations.

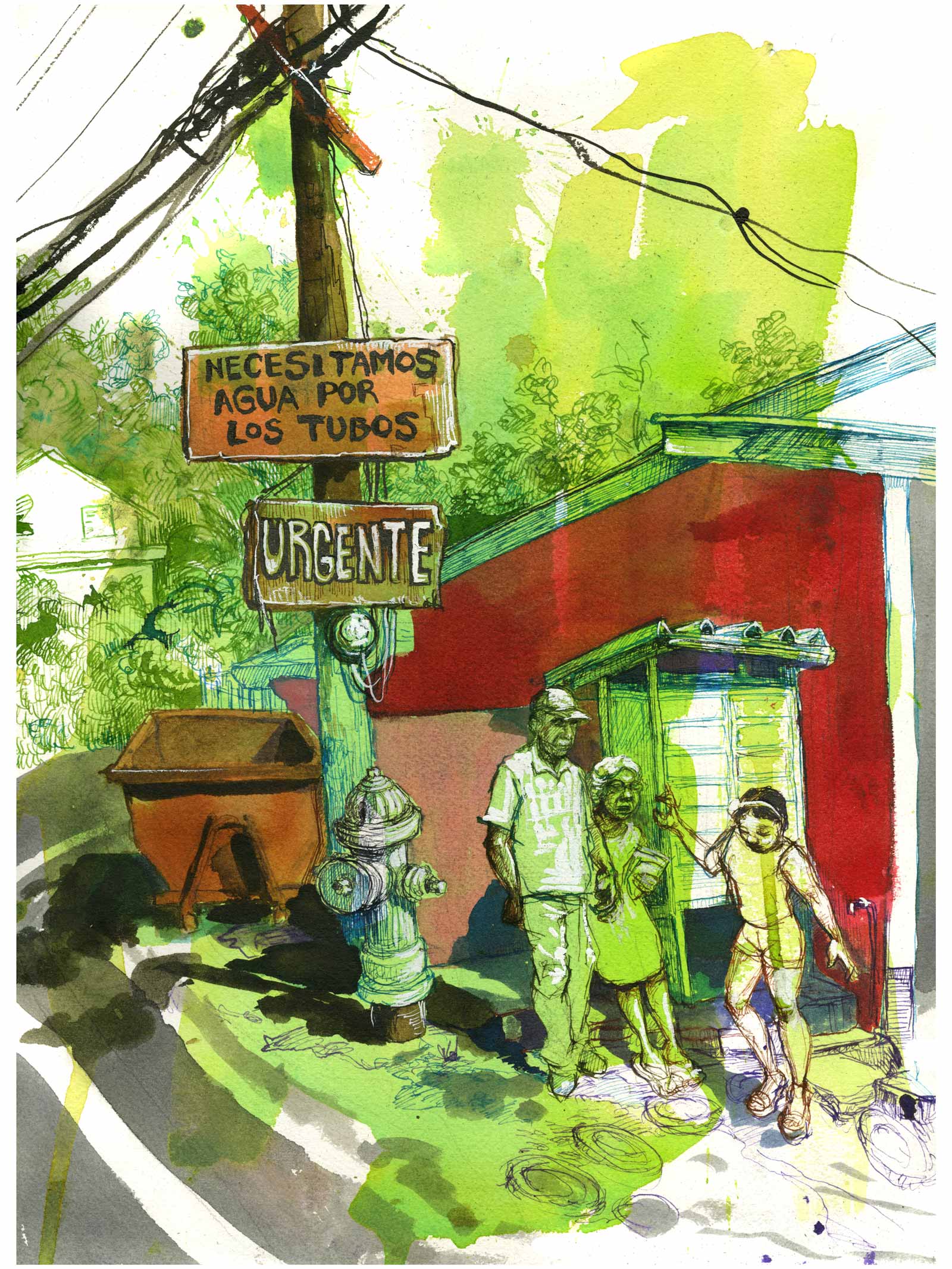

Barrio Cerro’s houses spill, favela-style, down the mountain. There was no running water when we visited; both electrical power and running water were sporadic even before Hurricane Irma last year. People had prepared for the storm, but not for the three weeks they would be trapped in the barrio by hurricane debris and mud too deep for even their horses to cross. The central government melted away and was, by necessity, replaced by community solidarity action. The barrio organized itself to cut down trees, gather trash, watch the kids, wade through the mud into town. In the first days, Rosado-Seijo collected tarps and generators donated by Nuyoricans. By January, he was focusing on rebuilding, not survival. There were workshops to give, and the community center needed solar power. How could they use gravity to get running water to people’s homes?

Electrical crews are already leaving Puerto Rico, and many mountain barrios will never have their power restored. FEMA pays little or nothing for the damage in the barrios, forcing people to leave their ruined homes. Take Rosa Luz, a nurse who had spent her entire fifty-six years in Barrio Cerro. She has a son in Florida and a lifetime of work behind her. Maria tore off part of her roof. Rain leaks through the tarp her brother stretched over the hole, the dampness spreading mold inside. Her house is empty except for water barrels and a shrine to the infant Jesus.

“House looks good,” FEMA said at first, before they blamed the damages on her. She had to sign a form swearing not to make false statements, on pain of arrest. During the months-long bureaucratic battle, she wept and lost weight. When FEMA finally sent a letter refusing to pay for repairs, she tore it up in rage. “It is God’s plan,” she told me, several months later. “We must accept everything with love.” The rain beat on the blue plastic tarp, which buckled but held.

… Puerto Rico

clings to my lips and in sobs clamors for you,

the stars of the North mocked its name,

humiliated its flag. They took the homeland away!

—From “To Rafael Trejo”

In Naranjito, in 1934, De Burgos published her first poem and married her first husband, a nationalist journalist named Rubén Rodríguez Beauchamp. The same year, doctors amputated her mother’s leg to deter the spread of cancer. And De Burgos embarked on her first of many tours, traversing the island by shared taxi, reciting her poetry to raise cash for her mom.

In 1936, when the Spanish Civil War was in bloody efflorescence, De Burgos and her husband moved to Old San Juan. On the island, another war raged between the US government and the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. In 1935, police gunned down four nationalists in Río Piedras. The next year, in retaliation for the killings, two nationalists, Hiram Rosado and Elías Beauchamp, assassinated the local police chief, Colonel E. Francis Riggs. Before cops killed him and his partner at the San Juan police headquarters, Beauchamp gave the cameras a jaunty salute. He was a cousin of De Burgos’s husband.

A month and a half later, a federal grand jury indicted eight nationalists, including Pedro Albizu Campos, on charges of trying to overthrow the government. De Burgos was on the committee to free the prisoners. Among the defendants were the famed poets Clemente Soto Vélez and Juan Antonio Corretjer—the latter was De Burgos’s lifelong friend. All those indicted received jail terms of between one and seven years.

On Palm Sunday, 1937, nationalists held a parade in Ponce to celebrate the anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico. The permit was cancelled at the last moment, but a small crowd marched anyway: girls holding flowers, nationalist cadets in their military uniform of black shirts and caps. The police opened fire. Their bullets continued to fly uninterrupted for a quarter of an hour, after which police hunted down stragglers. By the end, twenty-one lay dead, and over a hundred were wounded. It is not clear whether the mayor of Ponce or the US-appointed governor, Blanton Winship, ordered the attack.

The same year, De Burgos left Beauchamp. In Catholic Puerto Rico, this was one of many demerits attached, even after her death, to her name.

*

Today I want to be a man. Climb the adobe walls,

mock the convents, be all a Don Juan;

abduct Sor Carmen and Sor Josefina,

conquer them, and rape Julia de Burgos.

—From “Pentachrome”

When I visited four months after Maria, Viejo San Juan was slowly stirring to life. The Ateneo, Puerto Rico’s oldest cultural institution, finally reopened. The tourists started to filter back to old San Juan, drinking mojitos and taking snapshots of the Puerto Rican Tourism Company, housed in a building that was once La Princesa prison, which held so many nationalists in solitary confinement.

Here, De Burgos had supported herself by writing newspaper articles and plays for School of the Air, a radio show funded by the Department of Education. The translator of her poetry, Jack Agüeros, claims she was fired for her nationalist beliefs. But by then, she was on her way to becoming a legend. Mentored by the poet Luis Lloréns Tores, she published a flurry of work.

I imagined De Burgos in 1937, as she walked through the doors of the Ateneo to win her place in San Juan’s literary scene. I saw her dark hair against the cool white walls, the geometric tiles that evoked Spain’s Almohad dynasty. I could picture how she had had to fight.

De Burgos did not get along with most Puerto Rican literary women, pale daughters of the elite who couldn’t abide the expressive genius of the jíbara (the country girl). Eminences like Nilita Vientós Gastón, who became the Ateneo’s first female president, Isabel Cuchí Coll, later director of the Society of Puerto Rican Authors, were, to De Burgos, members of what she called “the innumerable line of gratuitous enemies of all sorts,” gossiping about her in life, slamming her work after death.

The year De Burgos separated from her husband, she self-published her first poetry collection. Another came in 1938. She toured the island selling copies. Despite her enemies, prizes piled up. She recited her work at the late-night gatherings of the poet Luis Palés Matos’s artistic circle. She counted as admirers Pablo Neruda and Juan Bosch, who was later president of the Dominican Republic before his overthrow by a US-backed coup. She was young, free, beautiful, and aflame with her literary power. Even the Ateneo held a night in her honor.

Into this milieu walked a socialist aristocrat, medicine salesman, and heartthrob to San Juan’s literary mean girls, the Dominican revolutionary Juan Isidro Jimenes Grullón, as if sent to smash up her world.

She had first met him in 1938 at one of his lectures in San Juan. Like many exiled dissidents, he would spend decades trotting around the globe, trying to hustle support by recounting his country’s traumas. Two days after that first meeting, she recited poems for him during a private meeting at Hotel Roma. He was impressed.

Grullón was some ten years her senior and a grandson of a two-time Dominican president. After graduating from the Sorbonne, he toured Europe, meeting Benedetto Croce and Henri Bergson. In 1934, he participated in a failed plot to overthrow the brutal Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. He spent a year in prison, for part of which he was forced to work as a slave in Nigua, where he saw fellow inmates die from torture and disease. Grullón was exiled from the Dominican Republic in 1935. In 1939, when his friend Juan Bosch formed the Dominican Revolutionary Party, he was a founding member.

Grullón was handsome and fastidious—he would later bemoan the harm his liaison with De Burgos had done to his social and professional standing. From the start, his parents did not approve. Their investigations revealed “that Julia was a great poet, but she was not a woman attached to the traditional values of home and family… [and] she had a tendency to dipsomania,” Grullón said in one of the interviews he later gave about her. During his later years, he liked to paint a picture for the press of De Burgos’s naïve talent and uncontrolled sexuality, and how each night, in the tiny rooms they shared, she stayed up till dawn scribbling her “Song of the Simple Truth” to him. Though Grullón outlived De Burgos by three decades, he would never forget the three years he spent as the love of her life.

*

I want to become the size

of God

to start a world

anew.

—From “Tardy, Without Wounds”

In January 1940, Julia de Burgos left Puerto Rico to follow Grullón to New York. She was bemused by the crowds obediently in step to the rhythm of traffic lights, and by buildings that reminded her of military barracks. Articles celebrated her in the Spanish press. She threw recitals. Parties were held in her honor. But literary glamor seldom comes with a paycheck. For a $25-a-week wage, she went door to door, collecting information for the US Census, then hiked down the inhospitable, sleet-driven streets to sleep on a cot in the hallway of a friend’s apartment. When Grullón left for Cuba, she gladly followed.

Her letters to Consuelo reveal many Julias. The woman in love. The sister, sending money home. The radical concerned with the Soviet Union, Puerto Rican independence, and the progress of the war. But there’s another Julia, less often mentioned, perhaps because careerism is a sin for women and for artists. The Julia of 1940 was a young writer on the make, ever more famous by her own design. She demanded copies of her press, plotted her events, gloried in her prizes, savored each compliment paid to her by every famous member of the literati. It was an absolute necessity, this Julia wrote, that she publish a book a year.

De Burgos and Grullón spent two years shuttling between Havana and the country towns where Grullón hawked medicines, outrunning Trujillista plots and financial precarity. He worked on his fourth book. She took classes at Havana University, with the ambition of earning four degrees in five years. She studied French, Latin, and Greek. She wrote. Despite Grullón’s professional envy and romantic jealousy, she carved out her place in bohemian literary life.

“I am happy in love, but a sword is always suspended above my head,” De Burgos wrote to Consuelo, the sword being Grullón’s family. Grullón’s mother sent defamatory letters to the Dominican community in New York and berated her son about the unsuitable, awful Julia.

On June 8, 1942, she left Grullón. Four months earlier, De Burgos’s favorite writer Stephen Zweig had committed suicide in Brazil in despair over Nazism. She, too, was mired in a personal abyss. So long as Grullón’s parents lived, he would never marry her. “To save something beautiful you must destroy it, so it does not fall, limp and degraded, from our miserable human hands,” she wrote. She left the man but decided to stay in Havana. Three weeks later, he presented her with a one-way plane ticket to Miami, boarding that afternoon. She had to leave behind most of her books, one of her frequent regrets in a life of so many male-induced displacements. According to Grullón, the CIA confiscated her passport when she landed.

*

You are like your world, selfish; not me

who gambles everything betting on what I am.

You are the ponderous lady very lady;

Not me. I am life, strength, woman.

—From “To Julia de Burgos”

She could have gone back to Puerto Rico, but she did not. The government crackdown had scattered her nationalist comrades, and perhaps she did not want to give those Ateneo ladies the satisfaction of her heartbreak. She returned to New York, where she made the best of it. Lacking the money to continue her education, she recited her poetry at El Barrio tertulias (gatherings) and wrote about culture for Pueblos Hispanos, the Spanish-language weekly in New York edited by her old friend Corretjer. When Grullón came back to New York to reclaim her, she had a new lover, a musician named Armando Marín.

The FBI file on Julia de Burgos begins in 1944. “Alcoholic” was listed as one of her “peculiarities.” The next year, she worked as a clerk in the Office of Intra-American Affairs, during a miserable stint in the D.C. suburbs, where she’d moved with her then-husband Marín. The FBI interrogated her. She was fired from her job and blacklisted.

She returned to New York, where she promised Consuelo “to continue, with more strength than ever, with what destiny put in my heart and in my pen for my people and for the other peoples of the world.” But, Pérez Rosario told me, after Pueblos Hispanos closed, Julia lost her platform. After 1945, she mostly disappeared from the published record. The newspaper articles that once celebrated her were replaced by swelling files of FBI reports.

What was truly to blame for her decline? Was it thwarted ambition? Government surveillance? Poverty? Her knack for stirring up jealous gossip? The racism and sexism any brown woman would have faced? In New York, she worked blue-collar jobs: power press operator, sales clerk, seamstress. She stormed out of a factory after fighting with fascists, quit a newspaper because the director was reactionary. Her marriage collapsed in stages. She drank. She had boyfriends. This kind of hard-living, fast-loving bohemianism might have been acceptable for a Hemingway; not so much for a Puerto Rican woman.

In 1948, cirrhosis forced her into the first of a series of long-term hospitalizations. Famously, she put “writer” as her profession on the intake form for Bellevue. Staff crossed it out and wrote in “suffers from delusions.” In the hospitals, her skull was measured. She was experimented on, injected with hormones, confined to a wheelchair, exhibited to medical students. The nurses exclaimed over her kinky hair.

She kept writing. Every time she was offered a ticket back to Puerto Rico, she declined.

In 1953, six weeks out of the hospital, Julia de Burgos collapsed on a Harlem street near Central Park, and died. She was thirty-nine years old. She carried no ID and, with no one able to identify her body, was buried in a potter’s field on Hunt’s Island. After a month of inquiries, her friends in Puerto Rico located her, had her body exhumed, and brought her home at last to Carolina.

During my visit, I could not see the memorial De Burgos’s hometown had built for its most famous daughter. It was closed because of damage caused by Hurricane Maria.

*

As I visited the places De Burgos had lived, I asked people about her significance after Maria. Some seemed surprised by the question, but others answered effusively. “She is part of our history of resistance,” said Stephanie Nieves Rio, a social work student who volunteered at La Olla Común. In moments of fear and uncertainty, she explained, Puerto Ricans needed be able to find people like Julia de Burgos in their history and see that neither their pain nor their struggle was new. “There is also the power that her words still have,” Nieves Rio went on. “When one reads them aloud, the whole world stops and listens.”

“I grew up with my mom unexpectedly reciting her poetry,” said Elizabeth Yeampierre, executive director of UPROSE, New York’s oldest Latino community-based organization. She explained:

I am my mother’s only daughter. She wanted me to be strong, independent and to study. My mom cleaned apartments, drove taxis and worked as a superintendent of a building. She wore overalls and long hair and she recited all of Julia de Burgos’s poetry. [Yeampierre quoted several lines of “To Julia de Burgos.”] This paragraph defies the expectations of men. Puerto Ricans are defying all expectations.

Some Puerto Ricans have seen De Burgos’s life in New York as a fall from Eden. But New York was always a hotbed of Puerto Rican nationalism, and indeed, the birthplace of Puerto Rican flag. Ramón Emeterio Betances, father of Puerto Rico’s independence movement, helped found the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico during one of his stints in the city, while, Luis Muñoz Marín (Puerto Rico’s first native governor and persecutor of the nationalists) idled years away on liquor and poetry in Greenwich Village. For Latino male intellectuals, a stay abroad was de rigueur. How else could they acquire the requisite perspective, worldliness, and polish? But while a man might leave the homeland, a woman was the homeland, and for her to go abroad was a ravishment or a betrayal.

My father told me that Americans used to say Muñoz Marín was too big for his tiny island. The statement drips with colonists’ condescension, of course, but it rings true for Julia de Burgos in a way it does not for Muñoz Marín. Julia de Burgos was driven out by the largeness of her talent, aspiration, and desire. The tragedy was that New York was too small for her, as well. America, in the early 1940s, had no space for a Latina woman of five-ten, her skin bronze and hair curly, her background working-class, her love life complicated, her politics leftist, her pride unbroken, and her talent confrontational and startling. De Burgos did not break because she left home. She broke because the world was too constricted for anywhere to be her home.

Back on the island, my father and I stood on the beach in Piñones, next to a shack selling bacalaitos, the salt cod fritters he remembered from years before. I pictured Julia as she had been at twenty-five, boarding the ship bound for New York—her bag heavy with books, her head full of plans for literary triumph. This same journey is a migration that Maria has forced upon hundreds of thousands of other Puerto Ricans. She would never return. Will they?

All quotations of Julia de Burgos’s poems are taken from Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos, translated by Jack Agüeros, published by Northwestern University Press (1995).