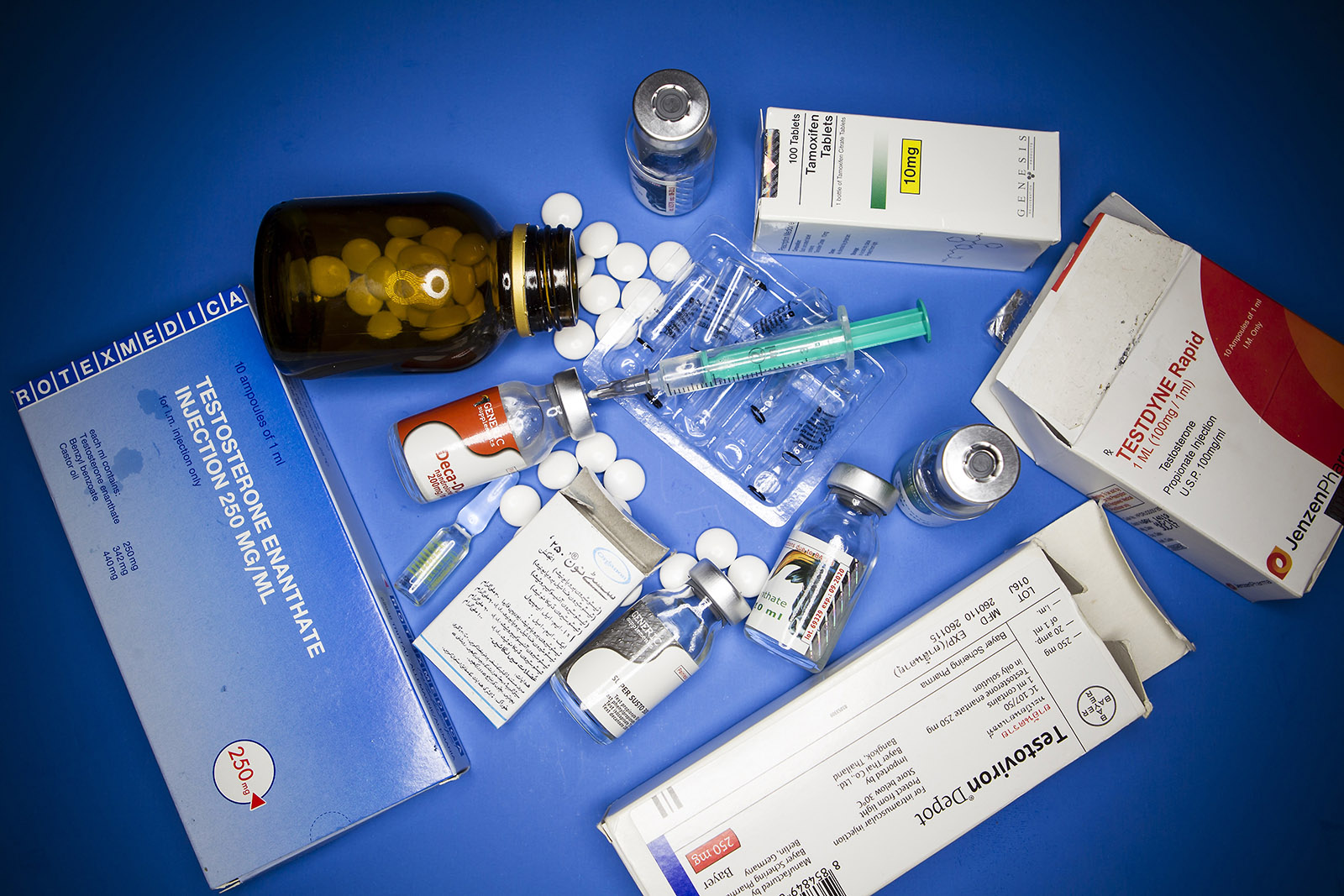

We live in a time of testosterone. Although the US Food and Drug Administration has approved testosterone products only for men with low levels resulting from a handful of medical conditions—and despite no observed increase in this population—prescriptions for “T” (as the hormone is colloquially known) rose over three-fold in the US (and a staggering twelve-fold globally) from 2000 to 2011, prompting a federal warning about potential abuses of the hormone and the risk of cardiac events it could cause. The $2 billion worldwide industry represents a fraction of T’s total market, however, as an untold number of other users acquire it from sources outside conventional medical channels and institutions. T’s powers—actual or ascribed—are in unprecedented demand.

Testosterone has been culturally endowed with aspirational, almost magical, qualities since before the hormone was first synthesized in 1935. Scientists told the first and most important stories about this hormone. One of the earliest came from a sensational speech delivered by the eminent physiologist Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard at a meeting of the Société de Biologie of Paris in 1889. He reported the miraculous effects derived from an elixir of blood, semen, and “juice extracted from a testicle, crushed immediately after it has been taken from a dog or a guinea-pig,” which he self-injected, eager to reverse “the most troublesome miseries of advanced life.” The first injection, he told the crowd, produced “a radical change,” including increased physical stamina, “facility of intellectual labour,” and a markedly longer “jet of urine.” The greatest effect by far was on his “expulsion of fecal matters.” Despite what appeared to be great promise, editors writing in what would become The New England Journal of Medicine quickly cautioned against the “silly season” that might ensue, warning that “the sooner the general public, and especially septuagenarian readers of the latest sensation understand that for the physically used up and worn out there is no secret of rejuvenation, no elixir of youth, the better.”

Brown-Séquard was building on the idea that testicular tissue contained the substance responsible for strength and virility, even for masculinity itself. In the decades that followed, scientists dedicated to uncovering the cause of observed sex differences looked where they understood them to be rooted, in the gonads. Unable to study testosterone directly because it had yet to be isolated in the laboratory, scientists castrated animals and observed which functions and tissues were affected, focusing on what they considered masculine effects such as mounting behavior in rodents. They then sought to restore the observed effects by implanting bits of testicular tissue. If the affected functions were restored, they attributed those changes to the glands and their secretions. But early experiments with so-called sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone) yielded findings that researchers described as “strange,” “paradoxical,” and “anomalous,” not least because the hormones were not sex-exclusive, and because their functions went well beyond determining sexual characteristics; testosterone, for example, influences many biological processes in all humans, including heart function, liver metabolism, and bone development.

These puzzling and contradictory findings did little to undermine the idea that testosterone was the “male sex hormone,” the molecular driver of all things masculine—a notion that still finds widespread support among sources as varied as researchers at the National Institutes of Health and reporters for The New York Times. That the hallmarks of testosterone have been yoked exclusively to men, and that the hormone’s effects credited as the primary drivers of sexual development and sex differences, are less a function of science than of ideology.

Even before its laboratory synthesis, this “chemical messenger of masculinity,” in the words of a Dutch researcher, was in search of a market. In the early part of the twentieth century, men who faced physical decline associated with aging sometimes subjected themselves to radical interventions in hopes of restoration (seeking to be a younger iteration of themselves), or transformation (seeking to be the person they wanted to be). No idea was too outlandish or overreaching. Injections of testicular extracts from guinea pigs, as well as grafts and implants of testicles from goats and chimpanzees were purported to remedy an astonishing range of ailments and conditions, including senility, dementia, diabetes, TB, acne, paranoia, and gangrene. Though some of these claims did have a basis in the scientific knowledge of the era (and, importantly, would later provide a foundation for hormone replacement therapy in clinical medicine), today we know that such procedures could not have worked. In some of the “transplants,” for example, the organ was simply sutured to other tissue.

Nevertheless, doctors hocked their procedures and newspapers heralded the amazing results including a “fountain of youth” in a newly-established chimpanzee breeding colony that would “place glands within reach of all”; journal articles reported patients with improved eyesight, increased appetite, and “a feeling of buoyancy, a joy of living, an increased energy, loss of tired feeling, increased mental activity and many other beneficial effects.” Beyond the doctors’ offices that men frequented in search of the miracles that could be had, pharmaceutical companies and their marketers, as well as researchers, elaborated with the aid of popular writers the many alchemical powers T was reputed to hold.

Advertisement

In the more than eight decades since the hormone’s isolation, testosterone’s appeal has expanded for reasons that go far beyond its supposed powers of rejuvenation. The universe of people using T, and the reasons for which it is used, transcend the categories “men” and “low testosterone,” respectively, by such magnitude that it is mind-bending even to list, let alone sort, them. Men, women, teenagers, the elderly, the healthy, and the sick all take T; and they do so to mitigate symptoms (lack of energy, depression), to boost attributes (muscle mass, vocal pitch, confidence), or to halt decline (brain fog, diminished sex drive). T is used to intervene not only in the “diseased” body, but also to optimize a desired state of being. People likewise take T to affirm their gender identity or to be read differently by others—menopausal women, flaccid men, and “gender hackers” included. Bodies are sculpted, and psyches are, too. T has become a powerful technology for the production of subjectivity, the most consequential of which is gender.

As a synecdoche and a vehicle for masculinity—its very nickname conveys a punchy charisma—T embodies longings of all possible dimensions and gravity. But the shared wellspring of those desires almost always involves a quest for masculinity and its signifiers, offering hope for what it might enact and enable. A magical substance with a padded résumé, T also remains a potent steroid with occasionally unpredictable effects that only sometimes align with these aspirations. Thus the transformations that testosterone effects, whether intended or not, can also elicit fear and disappointment. T has its own agency.

One of the more striking contemporary narratives in what we might call the T genre—stories that chronicle the use of T and uphold the hormone’s reputation— is Andrew Sullivan’s 2000 piece in The New York Times Magazine, “The He Hormone.” After being prescribed testosterone to counter HIV-related hormonal declines, Sullivan documented with both amazement and precision the changes his body and mind underwent: “I can actually feel its power on almost a daily basis.” He reported weight gain, a bulkier neck and chest, increased energy and strength, improved mood, and an “appetite in every sense of that word expanded beyond measure.” The changes were so immediate and dramatic and, dare I say, stereotypically masculine that he was prompted to generalize his personal experience to all men, ascribing the changes to T and thus to nature:

It affects every aspect of our society, from high divorce rates and adolescent male violence to the exploding cults of bodybuilding and professional wrestling. It helps explain, perhaps better than any other single factor, why inequalities between men and women remain so frustratingly resilient in public and private life.

The experience was evidently so profound that, more than a decade later, Sullivan was still reflecting that T “correlates very highly with what we think of as culturally masculine attributes: physical strength, risk-taking, competitiveness, ego and the constant desire to fuck.” He concluded that “the power of testosterone as a hormone should never be under-estimated… It reveals what we cannot deny about our nature.”

Put another way, the uneven distribution of these traits (thanks to higher or lower testosterone levels) is what propels men to the top of the social hierarchy and relegates women to second-class status. Testosterone, in this telling, explains male dominance as a phenomenon entirely determined by T.

What Sullivan is, of course, doing, as many others have done before and since, is telling stories. Stories about bodies and behavior, about gender, and about T that reinforce gender ideologies and assumptions about gender difference. These stories propagate false facts despite being based on embodied effects—many of them from individuals who are themselves taking T, but with plenty of corroboration from scientists, doctors, marketers, and influencers, all of whom have particular stakes in T’s powers. Though they may differ in their specifics, these stories share a resolute assuredness about the hormone’s effects that seems to foreclose more critical questions about the hormone and its capacities. They are stories that reinforce shop-worn ideas of male-female difference and attribute those differences to T.

The durability of these accounts is what recently encouraged Ira Glass, the host of the NPR show This American Life, to dust off “one of our very favorite shows,” which first aired fifteen years earlier, “about testosterone and just how much it determines our fates and our personalities.” The episode had included an almost comic laundry list of T’s greatest hits. In one segment, the producer interviewed Griffin Hansbury, a psychoanalyst specializing in gender and sexuality, who had taken T to the point of having what the producer characterized as “the testosterone of two linebackers.” Hansbury, like Sullivan, recounted a vivid change immediately after starting T: “Everything I looked at, everything I touched turned to sex.” And so a “big, shuddering, warm” Xerox machine became erotic, as did a red Mustang convertible that caused a “jolt in my pants, this very physical, visceral, sexual reaction.” The producer joked, “Testosterone didn’t just turn you into a man. It turned you into Rush Limbaugh.” Hansbury was sensitive to this, and troubled by it, saying, “I felt like a monster a lot of the time. And it made me understand men… And I would really berate myself for it.” And yet, he said, it made him feel like a man.

Advertisement

Women also tell these stories. In a first-person narrative in The Washington Post a few years ago, a woman described what happened when her doctor added testosterone to the hormones she was taking after her hysterectomy. Her narration, like Sullivan’s and Hansbury’s and many of the most animated accounts of being on T, was written very soon after the drug was first administered. She described looking at men as they passed her in an airport, after only two weeks on T: “I wanted to do them all. Men—young and old, thin and heavy, coiffed and shaggy… Not all rated attractive, but I found the idea of sex with each captivating.” The doctor had not mentioned the “constant sexual distraction. Or the irrational anger,” such as her rage at herself for dropping a fork, and at the mailman who “carelessly slammed a box onto the front steps.” When the woman went back to her doctor to describe her experiences, the doctor said, “Now you know what it’s like to have your brain bathed in testosterone.” Or, as the author put it, “What it’s like to live like a man.”

These testimonies share a sealed and confident view of T’s powers. By contrast, Maggie Nelson, writing in The Argonauts, a memoir filled with meditations on gender, laid bare an initial uncertainty about T’s capabilities, its potential effects, and its role as a necessary tool for masculinization or masculinity. Nelson related how her partner, the artist Harry Dodge, who “is happy to identify as a butch on T,” had chosen to take testosterone in addition to undergoing top surgery:

I suddenly remembered scouring the teeny print of a Canadian testosterone information pamphlet (Canada is light-years ahead of the United States on this front). I had indeed been trying to figure out, in a sort of teary panic, what about you might change on T, and what would not… you had begun to lay the groundwork to have top surgery and start injecting T, which causes the uterus to shrivel. The surgery didn’t worry me as much as the T—there’s a certain clarity to excision that hormonal reconfiguration lacks.

In her account, Nelson doesn’t specify the changes she fears, but that she is both uncertain and scared about the hormone’s effects while also cleaving testosterone from masculinity beautifully captures T’s complexity. “You’ve had a beard for years and already pass [for male] 90 percent of the time without T,” she writes. To many others, for whom T is ripe with overdetermined investments and desires, hormonal reconfiguration does have all the clarity of excision that Nelson pointed to regarding surgery. Where Sullivan is certain, Nelson is much less so. “As it turned out,” she concludes, “my fears were unwarranted. Which isn’t to say you haven’t changed. But the biggest change of all has been a measure of peace.”

What testosterone actually does to and for an individual is complex. When people want to know what T does, they usually start with the gender of the person using the T. What does T do for men? For women? This approach tends to assume that people within a given group take T for the same reasons or want the same results. It also assumes that the hormone will have similar effects in bodies within those groups. T’s effect for a given individual is inflected by that body’s particularity and history: its age; its current level of, including past exposure to, the hormone; the effects of habituation over time; the quantity, location, and sensitivity of androgen receptors; and the presence of other hormones. All these factors, many of which vary in response to social and environmental stimuli, play a part, as do dose and exposure to that dose over time.

When T is taken at higher doses some physical changes are likely, but T is more like a plated meal than a buffet: no one individual gets to choose precisely what changes it produces. As one friend who had started T said to me, “Let me know if you find a way to get the big muscles and keep the head hair!” It can fail people no matter how much they take, no matter how much they desire some effects but not others. For all the dramatic changes Hansbury experienced when taking T, he concluded that T let him down: he felt he had been more masculine as a “butch dyke.” He described asking people, “What kind of a guy am I?” The answer was not what he had hoped for:

They see a nerd, which I never was before. I was always really cool and popular and hip and whatever. And now I’m 5’ 4”, and I work out, but I’m not real muscular. And I’m pretty small. I’m pale-skinned, and my hair has started to thin, and I’ve got glasses. And of course, I’m also the sensitive guy now. I used to be the butch dyke, and I was seen as very aggressive. And I was more masculine in many ways—outwardly, anyway—before testosterone.

Clinical encounters often involve tempering expectations. As Ronica Mukerjee, a nurse practitioner who specializes in working with transgender individuals, told me, it’s important for those considering T to be aware of the unpredictable changes such as “whether people gain hair or lose hair, whether their body fat redistributes in a phenotypically cis-male pattern, and if their muscle mass significantly increases or not.” This uncertainty can be especially troubling if one’s reason for taking T is to be perceived as more masculine. Like Nelson, Mukerjee understands masculinity as independent of T. “For almost all trans masculine patients,” she told me, “the assertion and understanding of their selves and bodies as masculine happens regardless of testosterone initiation. But the lack of institutional and social acceptance for masculinity, without the addition of testosterone, can be part of the complex reasons that they initiate T.”

What T actually does cannot be easily separated from what one wants it to do. How do you ask a substance to make you more masculine or to give you a masculine trait without imbuing the changes that substance makes with your idea of masculinity? Even some of the earliest T experimenters wondered about what Brown-Séquard called “auto-suggestion without hypnotization.” There is no reason to think that ideas and ideals of masculinity are immune to the placebo effect. This doesn’t mean that what T does is entirely imaginary or unknowable, but it does mean our knowing should be far more nuanced than it is. Despite masterful appeals from the pharmaceutical industry, among others, to specific desires, such as increased libido, people approach T with different goals and desires. When people take T for its association with masculinity, it makes sense they would foreground and highlight what they understand as its masculine effects.

Consider, for instance, that we tend not to hear any of the magical stories of dramatic transformation from people who’ve been taking T for twenty years. Are the effects less noteworthy or just less novel? Do people settle into whatever changes took place, over time rendering them less remarkable? Or is it that we only hear from those who are most excited, most vocal? In the case of Hansbury, fifteen years later, does the Xerox machine still thrill?

I put these questions to Hansbury. He compared his experience to a young man’s passing through puberty: the tracking and noting of every feeling, behavior, and physical change, but also the curiosity and eagerness to see how these changes shaped how he was seen and how people interacted with him. This echoed what Sullivan described when he revisited the topic: “Twenty years ago, as it surged through my pubescent body, [testosterone] deepened my voice, grew hair on my face and chest, strengthened my limbs, made me a man.” But there is a crucial difference, Hansbury noted, between going through puberty and starting T. In the case of puberty, your peers are going through the same process as you are, which gives the experience a structure and context that is absent if the changes are happening only to you at age thirty.

The familiar stories have dominated to such an extent that it can be easy to miss any other version that doesn’t fit the master narrative. After starting T, Hansbury said in the radio interview, “I became interested in science, I found myself understanding physics in a way I never had before.” Even the interviewer squirmed at this—the interview subject had “reinforced a lot of stereotypes that we’ve almost dispelled with.” But there is a magnetism in these stories that seems irresistible. The uncanny correlation of taking T with suddenly understanding physics might slip by as yet another effect of T—except for how far-fetched it is. Rae Rosenberg, who self-describes as “genderfluid, femmy trans man” and who has also taken testosterone for about eight years, commented, “Maybe [Hansbury] caught a late-night Carl Sagan special, or got lost in a Wikipedia vortex on string theory. Maybe it’s just normal for people of all genders in their early twenties to find that they develop new interests.” Maybe it wasn’t T at all.

One of the most entertaining of contemporary T stories has been written by the gender theorist Paul B. Preciado, who, in his book Testo Junkie, recorded a year-long experiment of taking T in what he calls “DIY bioterrorism of gender.” Preciado, a keen and critical observer of both self and society, argues outright that “testosterone isn’t masculinity. Nothing allows us to conclude that the effects produced by testosterone are masculine.” And yet, this memoir is brimming with what one reader characterized as “bro-y braggadocio” that largely affirms the connection between the two. T created “excitation, aggressiveness, strength,” Preciado wrote, and an “explosion of the desire to fuck, walk, go out everywhere in the city.” It’s only by paying attention that the unexpected arises—such as the changes Preciado experienced in the domestic sphere: “testosterone compels me to tidy up and clean my apartment, frenetically, all night long… a profound and efficient sorting.” This is probably the first account of housekeeping mania attributed to T, not least because the dominant T story has never associated masculinity with domesticity.

What we know scientifically is not an adequate foundation for what people think T does for them. Take, for example, the recently-published testosterone trials in elderly men, which were conducted after the National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute expressed concern about the rapidly increasing number of men using testosterone and asked the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) to examine what was known about the risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation. Despite decades of widespread use, the IOM found insufficient evidence to conclude whether taking T improved libido, vitality, or cognition—and was equally inconclusive on any dangers it might pose. Conducted by medical researchers across twelve US communities, these double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, randomly designated elderly men to receive either T or a placebo for one year. The findings were almost the opposite of what we would expect: the effect on sexual function, physical function, vitality, and cognition were largely unremarkable; cardiovascular risks were raised. T did help with anemia and increased bone mineral density, but those are far less sexy, as it were, and not what has fueled the hormone’s popularity.

How, then, to reconcile these findings with the stories of raging libidinal improvement in middle-aged men? I don’t mean that T is immaterial, imaginary, or ineffectual, or that our scientific or experiential knowledge of T is completely false. Testosterone, in human beings, is necessary for health and well-being. But testosterone’s diverse aspirational powers are such that taking T is, at some level, an imaginative act. The experience must be powerful, heady, thrilling, all-consuming; and a person who is taking T knowingly seeking certain changes is someone highly attuned to any shift. The idea of feeling more “masculine” may be more powerful than the hormone itself—not least because T raises tricky questions about what the historian Joan Scott has called “the evidence of experience.”

Scott challenges the way that first-person experiences are often viewed as unassailable, beyond the reach of critique. “What could be truer, after all,” Scott asks, “than a subject’s own account of what he or she has lived through?” Scott argues that there is a danger in viewing personal narratives as incontrovertible evidence for the “fact of difference,” since doing so naturalizes the difference and obfuscates how our very experience is structured by social and historical forces and the interpretive frameworks we derive from them. There is no experience outside these constitutive conditions. This is no less true for our understanding of what T does.

In Andrew Sullivan’s generalization, for example, one might question his jump from his individual experience to that of all men, and then further to social structures. That is, from experiencing more masculine characteristics to his inference that testosterone therefore provides the biological basis for male-female hierarchies. There is a tautology embedded in his conflation of masculine traits with the social status they ostensibly confer. It is one thing, though, to say that testosterone exaggerates traits often associated with men, who are at the top of most traditional social hierarchies, and quite another to assert that it is testosterone that puts men there in the first place.

In Testosterone Rex, the psychologist Cordelia Fine argues that it is the way in which risk-taking and competition are defined and measured that gives the impression that men “naturally” excel in certain fields, and women don’t. It isn’t that women don’t compete or take risks—anyone defining competitiveness as exclusively masculine has never seen a mother trying to get her kid into the “right” school—it’s that researchers have conceptualized risk in traditionally masculine ways, focusing on entrepreneurial behavior, extreme sports, and sports betting, to name a few examples. Whereas, for women, Fine says, “quit[ting] or scal[ing] back your job when children arrive is a significant economic risk. Going on a date can end in sexual assault. Leaving a marriage is financially, socially and emotionally risky. In the United States, being pregnant is about twenty times more likely to result in death than is a sky dive.”

Nevertheless, upon hearing these stories, some want the hormone to bring about not a physical or behavioral change, but a social one. Løchlann, a friend in their forties (who goes by the pronoun “they”), has a slew of reasons for taking T, among them to “be taken seriously and paid what my male colleagues get.” They said this partly in jest, but it was also born of a deep and longstanding frustration about discrimination that I, too, feel. The gender differences that Sullivan and others take for granted as natural are social facts rooted in long histories of oppression, discrimination, and marginalization. It’s easy to see what would be attractive about the idea that a patch or pill can eradicate these problems for a given individual. When I point out to Løchlann that this locates the solution to a structural problem in an individual body and does nothing to lessen the broader effects of the gender hierarchy’s male and masculine bias, their answer was understandable: “That’s what I’m after. I’m so sick of being a second-, third-, fourth-class person. I’ve been trying to upset the gender hierarchy for fifty years. I’ve done my bit.” I get this, too.

Here, then, T is understood as a substance that can be leveraged for its presumed power to rectify inequity. This goal is reasonable considering T’s history of use by middle-aged men who seek to reinforce the conventional ideals of masculinity that, in turn, enable men to maintain their privileged position in the gender hierarchy. The problem with this view of T, though, is that by suggesting that bodies, rather than society, are the basis for differences that are used to justify gender inequities, it effectively dooms collective efforts to address those inequities and absolves those in power of their responsibility for sustaining them.

As the variety of people using T continues to expand, so do new possibilities for bodies, experiences, and subjectivities. In other words, even as T is used to shore up traditional ideas of sexual difference, it also destabilizes such difference. What if everyone had access to this “masculinity”? What could this chemical accomplish? What would masculinity even be? Preciado posits that T has the potential to smash the gender binary because it enables the expression of masculinity in bodies assigned female at birth. But as Hansbury also told me about his days as a butch dyke: “Female masculinity does not give you male privilege in our heteronormative, gender-conforming society. It doesn’t lead to a pay raise. Store clerks didn’t want to help me; they avoided me.”

For all the exciting ways that testosterone may be used to disrupt gender, can these expanded uses fully “seize the technology without buying the ideology,” as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English asked in their 1971 book Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness? A broader range of people taking T certainly complicates binaries of sex and gender, but to what extent will the result be to undo naturalized assumptions about gender difference and to what extent will it reaffirm the primacy of—and T’s coupling with—masculinity?

Sullivan recently raised the stakes when he accused feminists and their supporters of sidestepping natural male dominance: “in our increasingly heated debate about gender relations and the #MeToo movement, this natural reality—reflected in chromosomes and hormones no scientist disputes—is rarely discussed.” The cumulative effect of seeing these links asserted time and time again is what lends the nature argument its solidity. The T story has a perennial cycle that has proven exceptionally hard to interrupt, continually invoking views that remain widespread despite decades of incisive critique—everything from why women are underrepresented in STEM to why men are incarcerated more than women. But a constantly diversifying group of people taking T cannot by itself mitigate the problems of inequality that get pinned to T. Redistributing testosterone molecule by molecule will never dismantle regimes of power, but neither will the wholesale refutation of T. Demoting and disrupting its centrality in ideological conceptions of masculinity would make room for something better, though. And even that would be revolutionary.