The summer of 1937, the American model-turned-photographer Lee Miller, along with her ex-lover, Man Ray, and his Guadeloupean girlfriend, Ady, sailed to Southampton from France. Instead of then traveling on to London, as might be expected, they headed southwest to Plymouth, to meet up with Miller’s latest paramour, the British painter (and soon to be co-founder of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London) Roland Penrose. He and Miller had met only a few weeks earlier, at a Surrealist costume ball.

Just that night, Miller had arrived back in Paris after three years’ living in Egypt with her husband, the wealthy industrialist Aziz Eloui Bey. What had begun—after a whirlwind romance and a speedy marriage in a Manhattan registry office—with the promise of an exotic adventure eventually began to stifle Miller, and she longed to be back in the City of Light, where she’d lived, loved, and, most importantly, worked in the late 1920s. Man Ray had taught her everything she needed to know about photography before she set up her own studio in Montparnasse, thereafter relocating to New York.

From Plymouth, Penrose immediately whisked the trio down to Cornwall for what he called a “sudden Surrealist invasion.” He’d rented his brother’s house, Lambe Creek, for the best part of a month, and had invited a host of friends to join him: Paul and Nusch Éluard, E.L.T. Mesens, Herbert Read, Eileen Agar, Joseph Bard, Max Ernst, and Leonora Carrington. This was precisely the artistic milieu Miller had been longing to return to.

Gathered together in the second room of The Hepworth Wakefield’s excellent new show “Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain,” in West Yorkshire, is a selection of candid snaps both Miller and Man Ray took during their Cornish adventure. Most arresting is Miller’s photograph of an all-but-nude Carrington reclining in the sun, eyes closed, a smoldering cigarette clutched between the fingers of her left hand, with Ernst sitting behind her, his veiny hands clasped over his lover’s bare breasts, his head resting lovingly on hers, one half of his face hidden in a cushion of her thick, curly dark hair.

This sudden Surrealist invasion is integral to the story told in the Hepworth exhibition. It’s the beginning both of Miller’s engagement with British Surrealism, and of the life she and Penrose went on to build together. After her divorce from Bey, the couple eventually married in 1947, the same year their son Antony was born, after which they lived in East Sussex. Their house and gardens at Farley Farm became, and remain to this day, an unofficial gallery space for their work and that of their friends. Images taken there evoke the same carefree, communal living as seen in Cornwall, an existence in which extraordinary art—both in its making and its display—and everyday life are seamlessly intertwined. Miller’s 1953 photograph shows Henry Moore cheekily hugging his Mother and Child sculpture on the lawn; and in the image just next to it in the exhibition, Antony Penrose and Moore’s daughter Mary play together on the grass in front of Mary’s father’s work.

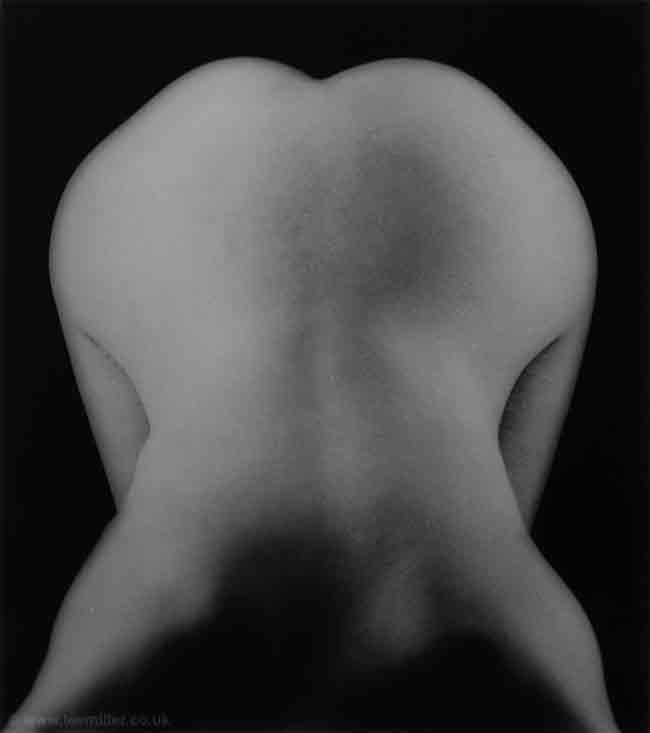

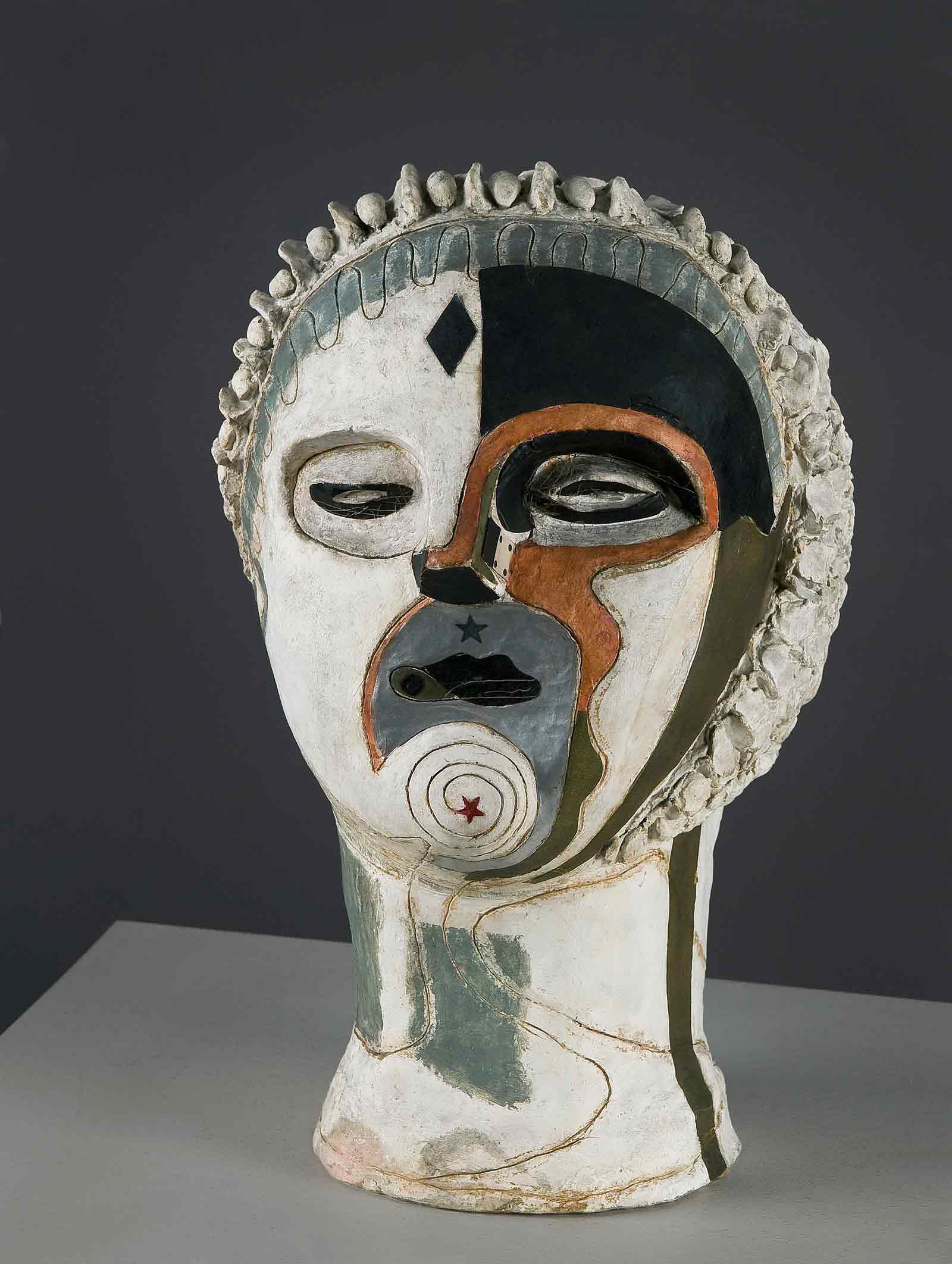

Ernst’s poster for the first International Surrealist Exhibition (1936) at London’s New Burlington Galleries hangs on the wall adjoining that of the Cornwall invasion scenes. René Magritte’s The Future of Statues (circa 1937), a plaster head painted as a blue sky covered with clouds, is hung up high, watching over the other works. Dalí and Edward James’s immediately identifiable Aphrodisiac Telephone (Lobster Telephone) (1938) sits in a vitrine, behind which a series of Penrose’s eerie pastel-hued paintings adorn the wall. His sculpture, The Last Voyage of Captain Cook (1936/1967)—a plaster female torso entombed inside a steel cage of a globe—stands in pride of place as you enter this second room, the largest of the exhibition’s three spaces.

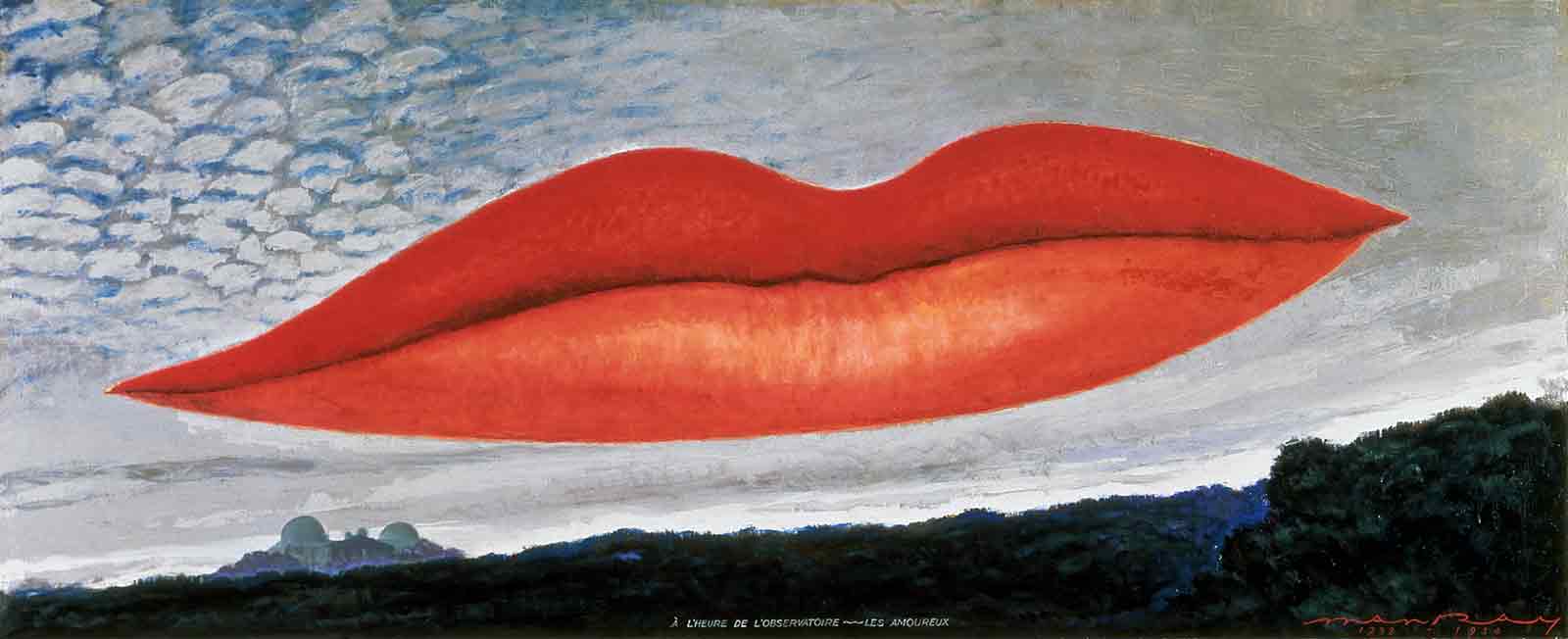

Much of the work here isn’t by Miller, not least because she herself didn’t show anything in the 1936 exhibition, though she was present—it was her luscious red lips that floated in the cloudy sky in Man Ray’s A l’Heure de l’Observatoire – Les Amoureax (1932–1934/1970); instead, it’s the output of her contemporaries that take center stage. There’s a cabinet of original issues of the London Bulletin—the pre-eminent publication of British Surrealism, which ran from April 1938 to June 1940—as well as paintings by Ernst and Carrington. It’s a selection that’s been carefully considered; it doesn’t overwhelm, but it does convey both substance and scope. The exhibition’s curator, Eleanor Clayton, has pulled off the near-impossible feat of breathing fresh life into Miller’s now immediately recognizable images, not an easy task given the previous exhibitions that loom large in recent memory. Clayton also achieves the necessary balance between shining a spotlight on Miller—acknowledging, too, Miller’s truly astonishing life, soon to be fictionalized in Whitney Scharer’s forthcoming novel The Age of Light—and illuminating the broader world within which she worked.

Advertisement

There’s perhaps no better symbol for this than the very first piece in the show: Man Ray’s Object of Destruction (1932), a metronome, with a paper cutout of a photograph of Miller’s eye attached to the ticking arm. Conceived in the immediate aftermath of his and Miller’s painful break-up, it came with the following instructions: “Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.” A loud, and insistent “tick-tock, tick-tock” provides the exhibition’s soundtrack (though to avoid driving anyone to distraction or madness, it is played only in short bursts). The piece represents Miller as subject, but Clayton has cleverly prevented this being our take-away by surrounding the walls of this first small room with examples of Miller’s own early work, images taken during her Parisian apprenticeship with Man Ray. Miller’s eye is the emphasis here—this is an exhibition about what she saw, not what others saw in her.

The show dissects both the trope of Miller-as-muse and the female body-as-object more generally in a series of swift, sharp slices. Behind the Object of Destruction are Miller’s uncanny photographs of two severed breasts, Untitled (Severed Breast from a Radical Surgery in a Place Setting 1 and 2) (circa 1929). Carved by medical students in an operating theatre but served up here on china plates complete with place mats and cutlery like something out of a macabre version of Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook (1932), the diptych inspires a gruesome double-take. Move into the next room and Miller’s lips in A l’Heure de l’Observatoire – Les Amoureax, (another work Man Ray made following their break-up) are impossible to miss. Just as Miller used her time with Man Ray to learn to be the artist rather than the subject—“I’d rather take a photograph than be one,” she famously declared—it seems that the end of their affair necessitated for Man Ray a figurative disembodiment of his one-time muse. First her eye, then her lips; he broke her apart bit by bit.

Images of the fragmented female body continue to be found throughout the exhibition. A familiar aspect of Surrealist art, of course, but all the more uncanny when viewed through Miller’s camera lens, images like Untitled (Woman with Hand on Head) (1931) and Floating Head, Mary Taylor (1933) subverting the traditional photographic portraiture of the period. In both, Miller reduces beautiful women to lone appendages, like creatures one might encounter in a sideshow of circus horrors. Also recreated here is Le Baiser, Miller’s long since lost contribution to the “Surrealist Objects and Poems” exhibition that Penrose organized in 1937 at the London Gallery: a wax arm, the sort one would have found in a manicurist’s salon, wearing a bracelet of false teeth. Miller, who had returned briefly to Egypt at the point, sent Penrose instructions for its creation, their correspondence a heady cocktail of creative and sexual passion. “I shall love to choose a hand as nearly like yours as possible,” he wrote to her in November, “and decorate it with teeth as nearly like mine as possible.”

The third and final room holds Miller’s works made during and after the war—we see, for instance, Miller’s scrapbooks for the ICA’s 1953 exhibition “Wonder and Horror of the Human Head,” which prefigured Pop Art’s merging of high art and popular culture. And it is here that we encounter the most surreal work of all, an image so famous that it’s been reprinted over and over since it first appeared in the July 1945 issue of Vogue: a photograph of Miller scrubbing away the grime of battle in the bathtub of Hitler’s Munich apartment, taken the day news of his suicide was broadcast to the world.

Advertisement

With this culmination, the exhibition encourages us to view Miller’s astonishing photojournalism as more than just documentary evidence. She ignored the ban on women journalists in combat, documenting the liberation of Paris and, later, the German surrender. She was one of the first reporters to enter Dachau and Buchenwald, where she photographed a heap of corpses to create an image that was without precedent for a publication like Vogue, which published it in the June 1945 issue, under the title “Believe It.”

Vitrines in the center of the room displaying various issues of Vogue from this period bring to mind the artistry of Miller’s elegant fashion photo shoots, juxtaposed with her images of the all-too-real hellscapes of Europe. That she moved so effortlessly between two such contrasting subjects demonstrates the impressive range of her vision. When it comes to the latter, although there’s no attempt to disguise the horror of what she sees, her Surrealist eye makes her the perfect observer, both of the banality of evil evoked in her carefully composed bathtub image, and the utter senselessness of the destruction all around her: her description of houses “crushed like hardboiled eggshells” in her report from Berchtesgaden and Munich “Hitleriana,” is more evocative than many of the more straightforward eyewitness accounts. Then again, that’s exactly what this endlessly fascinating exhibition reveals—that Miller was a woman who saw things differently.

“Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain” is on view at The Hepworth Wakefield through October 7.