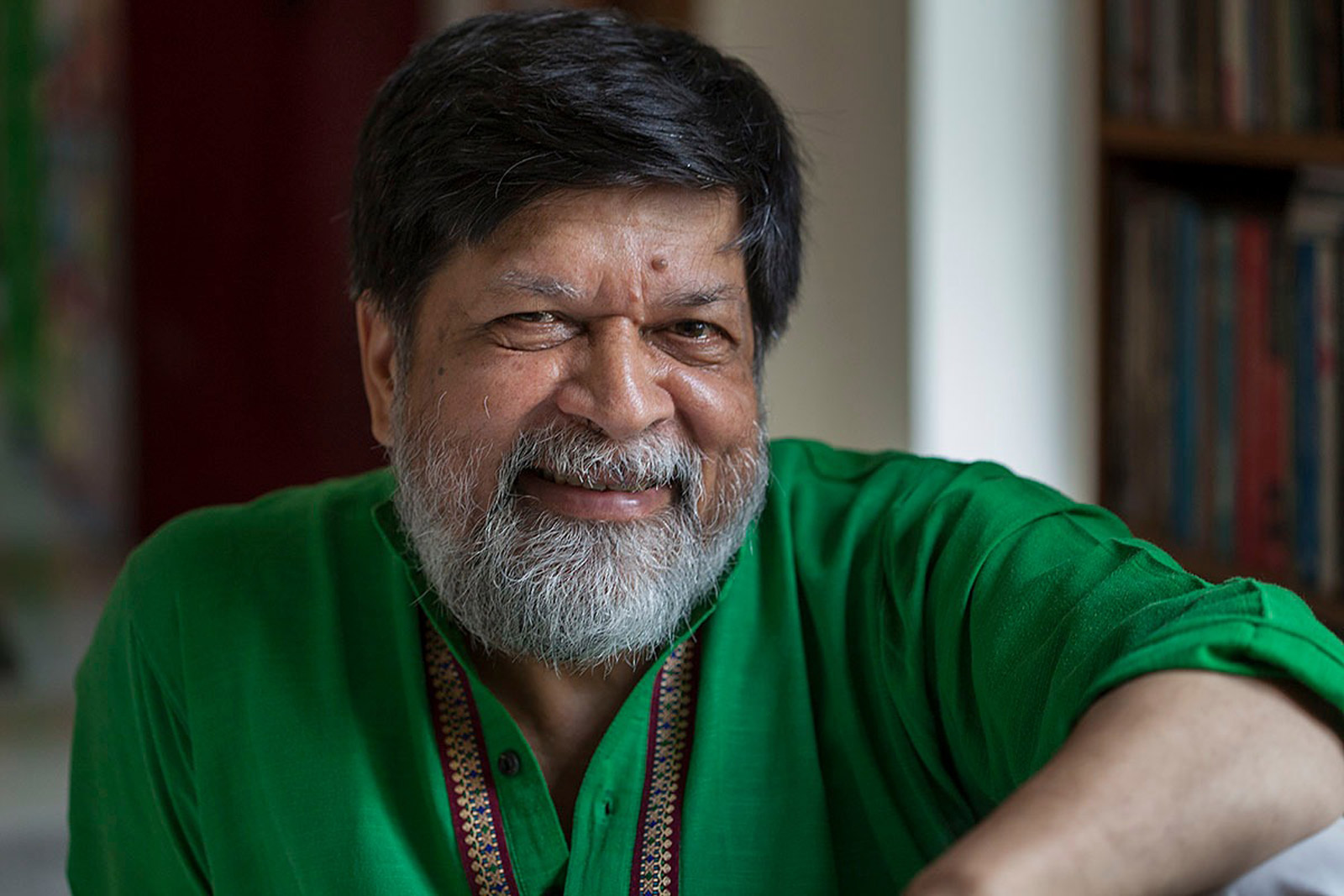

The renowned photojournalist Shahidul Alam is supposed to be in New York on October 28 to receive a humanitarian award from the Lucie Foundation, which honors photographers every year. Alam is a worthy recipient. His career goes back to the mid-1980s when he returned from Britain to his native Bangladesh with a doctorate in chemistry and, noticing his home in political turmoil, decided to record the democratic struggle to end General Hussain Muhammad Ershad’s autocratic rule with a camera.

Through his lens, he went on to capture the human drama around him—children growing up in poverty but displaying joy and resilience across the country; human rights defenders fighting for minorities, including the Chakmas and the stateless Rohingyas being driven out of Myanmar; and the spirit of Bangladeshi lives confronting great adversities—working in brick kilns, in garment factories, in makeshift ship-breaking facilities along the coast.

Alam’s 2011 memoir is called My Journey as a Witness, and he has been an exemplary witness for his nation. At the Drik photo agency that he set up in Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, Alam maintains an important archive of images of Bangladesh’s liberation war of 1971, when the country gained independence from Pakistan. And through Pathshala, the photography school in Dhaka that he also runs, he has trained hundreds of young photographers in South Asia.

There is no guarantee, however, that Alam will be able to attend the ceremony. Late in the evening of August 5, about thirty-five plainclothes security officers raided Alam’s home in Dhanmondi, an upscale area of Dhaka, and arrested him. The police masked the building’s closed-circuit cameras—a necessity in a city where crime is rising—and confiscated the earlier footage. When he was taken to court the next day, Alam was limping, and as he was taken away, he shouted to journalists, saying he had been beaten up while in custody: “My bloodstained shirt was washed and put back on me.”

Alam’s legal team managed to appeal to a higher court, which ordered that he be taken to a hospital and examined by a physician who can investigate torture. But over the weekend, Alam was moved to another jail and charged with spreading rumors and hurting the image of Bangladesh. On August 13, UN human rights experts called for his immediate release, but as of this writing he is still imprisoned.

Hours before his original arrest, Alam had given an interview to the Al-Jazeera network in which he had criticized the government crackdown on students who were protesting against worsening road safety. Earlier that day, Alam had gone out to see their protests and had begun photographing the unrest when men whom he described as “goons” smashed his equipment and chased him away.

The students had taken to the streets because of a July 29 incident in which the driver of a private bus, competing with the driver of another private bus to pick up passengers near a stop, had rammed into a group of students who were attempting to cross a major road, killing two of them and injuring twelve others. Road safety is notoriously poor in Bangladesh. According to the national committee to protect shipping, roads, and railways, 7,397 people died on Bangladeshi roads last year, and the figure for this year had already reached 2,471 in June. Driving standards are lax, with many unlicensed drivers, a high proportion of unroadworthy vehicles, poorly lit highways, malfunctioning traffic signals, and ill-maintained roads.

The government seems to have abdicated all responsibility for this state of affairs. Angered by the recent deaths, thousands of students, including some children in school uniforms, blocked roads and demanded to see drivers’ papers, letting pass only those whose documents were in order.

Students in Bangladesh have a long history of political activism. In 1952, they were at the vanguard of the movement to recognize Bengali as the official language of East Bengal, then a province of Pakistan, sowing the seeds of the independence movement that led to Bangladesh’s split from Pakistan in 1971. In December 1970, the Bengali-led party the Awami League secured an absolute majority in East Pakistan’s parliamentary elections. While the Awami League represented the strong Bengali nationalism that had emerged with the language movement, the party embraced secular-democratic values. Its charter called for greater autonomy for East Pakistan, a demand that was anathema to the politically-dominant West Pakistan. The military ruled Pakistan at the time, and instead of accepting East Pakistan’s election outcome (in which the Awami League, which had fielded candidates only in East Pakistan, surprised the military leadership by securing an absolute majority, which would have meant letting it form a government), Islamabad sent troops in March 1971, even as negotiations between the federal government and the Awami League were still going on.

Advertisement

The Pakistani authorities arrested Awami League politicians and pro-independence political opponents, and carried out a massacre in which hundreds of thousands died. The mass-killing began at the university campus in Dhaka; the first victims were students and academics. Many students joined the Mukti Bahini, as the Bangladeshi liberation movement was called, and with the support of Indian armed forces, waged a guerrilla war. Some ten million refugees escaped to India. Pakistan attacked India itself in December 1971, giving India the legal justification to intervene militarily, and two weeks later, Pakistan surrendered, paving the way for Bangladesh’s independence. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Awami League leader in Pakistani jail, was released; he made a triumphant return to Dhaka and formed a government, promising to secure Bangladesh as a secular, liberal republic. (The current prime minister of Bangladesh and leader of the Awami League, Sheikh Hasina Wazed, is his daughter.)

Mujibur Rahman was assassinated in 1975, and chaotic months followed. In 1977, General Ziaur Rahman took over as president. He, in turn, was assassinated in 1981, and General Hussain Muhammad Ershad declared himself president the following year. Once more, in 1990, it was the students who led the protests that challenged autocratic rule. As the popular uprising against him grew, Ershad was forced from office by, among others, Sheikh Hasina. (After Ershad’s ouster, the presidency became a largely ceremonial post; executive power lay instead with the prime minister, in a parliamentary system.)

This summer, students’ demands were for something far more modest and straightforward: safer roads. But the government of Sheikh Hasina did not appreciate their show of defiance. As the current student protest entered its second week, on August 3, young men belonging to two ruling party-affiliated leagues, Chhatra (students) and Jubo (youth), disrupted the demonstrations. Armed with machetes and sticks and wearing helmets so that they couldn’t be identified, they began attacking students and journalists to break up the protests. Alam witnessed all this and began recording—and then told Al-Jazeera what he’d seen.

And so the government arrested him. In theory, Bangladesh recognizes freedom of speech, but in practice, it places restrictions on it. In recent years, the government has significantly circumscribed what can be said openly. Since 2015, there has been a series of murders of secularist and atheist bloggers by Islamist extremists in Bangladesh, yet the government would not outright condemn the killings. Instead, Awami League supporters cautioned such bloggers to avoid offending religious sentiment.

International condemnation of Alam’s arrest has been swift. Groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and PEN International (whose Writers in Prison Committee I chair), as well as writers like Noam Chomsky and Arundhati Roy and the photographer Raghu Rai, have all registered protests against Alam’s arrest and called for his release. But the government seems to be hardening its position.

Sheikh Hasina’s son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, made a confusing statement suggesting that just because Alam is prominent and famous does not mean he can incite students with impunity. But Alam incited no one. Meanwhile, the preliminary police investigation, which must be filed before Alam can be charged, ascribes statements to Alam that he has not made. In his Al-Jazeera interview, Alam outlined a long list of the government’s shortcomings. He mentioned bribery, which has been rising, and questioned the government’s accountability on the grounds of its doubtful electoral mandate. The Awami League owes its current parliamentary majority (234 seats out of 300) in large part to the major opposition parties’ boycott of the last elections.

New elections are due soon, but the opposition is in disarray. One leading opponent, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, is effectively leaderless, since its head, former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia (widow of General Ziaur Rahman), is in jail on corruption charges. To that, add the deadly toll of extrajudicial killings in a so-called war on drugs (more than a hundred people summarily executed in recent months); and a rising number of disappearances of political dissidents, at the hands, many suspect, of shadowy government-linked agencies.

In this political environment, in which Hasina faces virtually no challenge to her rule, the government feels empowered to stifle all forms of dissent. Those who even appear to stand in the way, including a former chief justice, other opposition leaders, and certain journalists, are criticized by ruling party supporters and politicians as “collaborators,” a slur that tries to tag them as opponents of Bangladesh’s independence movement. One prominent critic of the government, Mahfuz Anam, editor and publisher of The Daily Star, faces dozens of politically motivated lawsuits.

The government’s anxiety is surprising, considering it faces no real opposition. Hasina is probably calculating that, aside from criticism from some NGOs, the international community won’t bother her because her government has performed the important task of providing asylum for hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees who recently fled murderous persecution in neighboring Myanmar. With nearly 800,000 displaced Rohingyas now in southern Bangladesh needing to be looked after, none of the major donor countries—the US, the EU, and Australia—want to alienate Bangladesh. Nor is Hasina likely to come under any pressure from Bangladesh’s closest regional ally, India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is facing elections there in a few months, and he wants to crack down on Bangladeshi migration into Assam, which neighbors Bangladesh. Modi would also like to expel some 40,000 Rohingyas elsewhere in India, a decision human rights lawyers have challenged in Indian courts; if he succeeds, Bangladesh would likely be the refugees’ ultimate destination. Finally, although her government has done little to protect secularist bloggers, Hasina presents herself to the international community as its partner against fundamentalist terrorism.

Advertisement

Hoodwinking international donor countries and suppressing internal dissent, Hasina hopes to be re-elected virtually unopposed. Noisy students, witnesses taking photographs, and critical journalists have been warned.