Shortly after the architect and theorist Robert Venturi died on September 18 at the age of ninety-three at his home in Philadelphia, I was asked by a design journalist if I still stood by the opening sentence of an article I wrote for the New York Review in 1997: “Among all living American architects, only two—Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi—now seem unquestionably assured of a permanent place in the history of their art form.” “Yes,” I replied, “I certainly do,” but with a touch of mischief added, “Only now I’m not so sure about Gehry,” a reflection of my increasing disillusionment with much of that architect’s output since he completed his Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles fifteen years ago.

However, by 2007, when I collected that essay, along with sixteen others I’d done for the Review, for the first volume of my Makers of Modern Architecture series (the third installment was published a week after Venturi’s death), I had revised my original opening:

Among all American architects since Louis Kahn, who died just before the final quarter of the twentieth century, only three—Frank Gehry and the husband-and-wife team of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown—by the end of the century seemed guaranteed a permanent place in the history of their art.

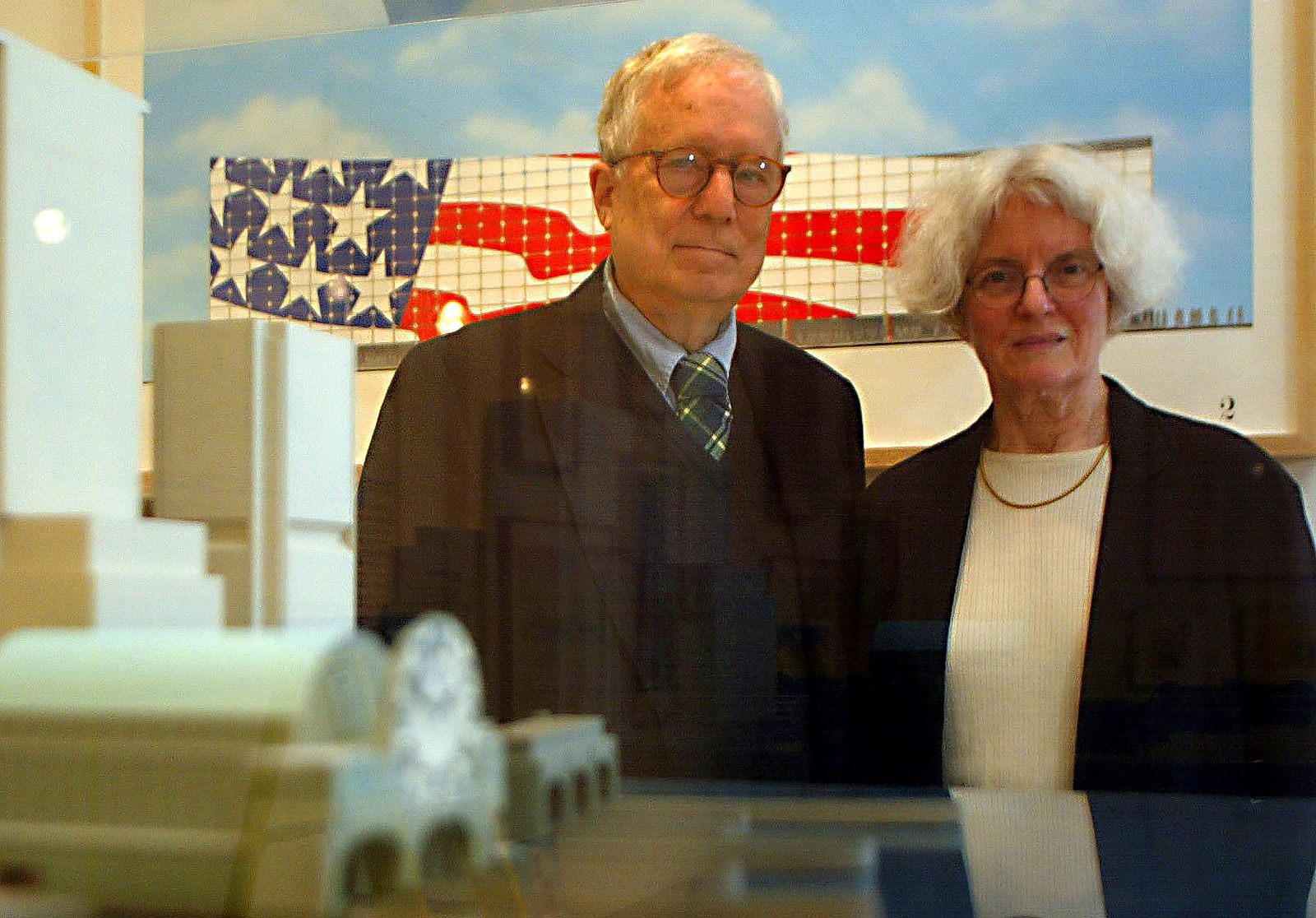

This change reflected my gradual understanding that Scott Brown—Venturi’s chief collaborator from the time she joined his Philadelphia office in 1969, two years after they married, until he retired in 2012 as he was affected by the Alzheimer’s disease that took his life—had been given far too little credit in their partnership. This occurred even though Venturi himself always took great pains to stress that she was no mere helpmeet, but instead a full co-creator, an assertion that for many years fell on deaf ears.

The unfortunate misapprehension to the contrary was given unintended credence when the 1991 Pritzker Prize was awarded to Venturi alone. The sponsor’s explanation for this snub was that the award was created to honor individuals, not firms. (That position was reversed in 2001 when the Swiss team of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron was chosen, and twice since then, it has been bestowed on multiple-partner practices.) Regrettably, Venturi and Scott Brown, who were eager to benefit from commissions that often result from winning the accolade, accepted the humiliation, although she declined to attend the award ceremony. Some observers felt they should have outwaited the Pritzker jury until their being overlooked as a team became a scandal, but they feared the parade would pass them by.

As the partners’ historic stature loomed ever larger, support grew for retroactive conferral of the award on Scott Brown, but a 2013 online petition in support of that was rejected by the Pritzker committee with obtuse officiousness. This was not the least of their problems, for the pair was widely held to be most important not for their architecture at all but for their hugely influential writings, which include his seminal Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) and the controversial Learning from Las Vegas (1972), written by Scott Brown, Venturi, and their younger associate, Steven Izenour.

But the two were, in fact, responsible for several of the most singular buildings of our time. Among them are his Vanna Venturi house of 1959–1964 in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania, whose famous split pediment was an architectural “shot heard round the world”; their Sainsbury Wing of 1986–1991 at the National Gallery in London, which channels the spirit of the Florentine Renaissance to exalt the paintings it displays; and their Capitol of the Department of Haute-Garonne of 1992–1999 in Toulouse, France, an under-appreciated masterwork of Mannerist sophistication and civic engagement.

These assignments were the antithesis of the couple’s less frequent but more provocative and newsworthy riffs on electronic signage and quirky roadside oddities. Most celebrated was their enthusiasm for the Big Duck poultry stand of 1931 in Flanders, New York. Scott Brown likened this masterpiece of ferroconcrete folk architecture to the aggressively sculptural constructs of late Eero Saarinen and mid-period Paul Rudolph—the “duck” she and Venturi rejected in favor of their preferred form, the “decorated shed.” This was a generic, boxy enclosure fronted by a billboard-like façade that announced a building’s function through pattern and graphics, and permitted greater flexibility thanks to its undifferentiated volume.

Prime examples of this concept were two big-box stores: their Best Products Showroom of 1973–1979 in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, its exterior walls adorned with a Warholian floral print, and the Basco Showroom of 1976–1978 in Philadelphia, with the company’s name spelled out in thirty-four-foot-high cutout letters that towered in front of the banal single-story structure like the famous Hollywood sign; both works have been demolished. More enduringly, the decorated shed format turned out to be ideal for the several science facilities they designed, where future functional demands are largely unpredictable and so benefit from such forgiving and adaptable internal configurations.

Advertisement

Their work on college campuses across the country, the largest portion of their oeuvre, displayed a pragmatic common sense that they were rarely credited with by those who saw them and their designs in cartoonish terms. The most strident of those detractors was Tom Wolfe, whose bestselling 1981 neoconservative diatribe, From Bauhaus to Our House, heaps as much scorn on Venturi as it does on Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Gropius, and other founders of the Modern Movement. Tellingly, Scott Brown merits not a single mention from this arch chauvinist.

The officiant at Venturi’s ecumenical funeral, which was held in a Quaker meetinghouse near Philadelphia, was Father John McNamee, a retired Roman Catholic priest who had been the de facto client for the firm’s 1968 renovation of the city’s Byzantine-style St. Francis de Sales Church, a commission that sought to promote innovations in worship decreed by the recent Second Vatican Council. The architects’ massive freestanding altar faced worshippers and was flanked by a lectern and a high-backed chair for the celebrant; these coolly Minimalist designs were executed in white Plexiglas.

Laterally suspended above them was a sinuous, bell-curve of white neon to demarcate the sacred space. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the church’s mainly working-class parishioners saw this hovering light sculpture (akin to contemporaneous work by avant-garde artists including Dan Flavin) neither as a luminescent halo nor as symbolic of the Holy Spirit descending upon them, but associated it instead with beer signs in bars and delis. As Father McNamee told me, brides in particular disliked the way the neon light made them look, and insisted that it be switched off during their wedding ceremonies; the fixture was eventually removed.

Venturi and Scott Brown’s use of such vernacular materials in their buildings, which often had a purposefully flat affect, was widely misunderstood. Their irreverence sometimes alienated less imaginative clients and disqualified the couple from certain kinds of commissions. But rather than being ironic and condescending, the partners’ commercial and quotidian borrowings represented their belief that “Main Street is almost all right,” and that there is much to be learned from popular taste. Their support of a more egalitarian, inclusive approach to high-style architecture might have been their most important accomplishment.

Although several obituaries called Venturi the father of Postmodernism (or, in the case of London’s Daily Telegraph, the movement’s grandfather), he and Scott Brown rejected that association wholeheartedly, even though Venturi’s first book is considered the foundational text of Postmodern architecture. As he put it in a 2000 interview, “Freud was not a Freudian… Marx was not a Marxist, we are not postmodernists.” Obscured by that label, they felt, was the strong social motivation that informed so much of their housing, university buildings, and museums, the basis of their professional practice and the lion’s share of their work that was built.

They much preferred to be called Pop architects, which correctly linked them to the American artists of the 1960s with whom they had so much in common. Venturi’s only contemporary rival as a draftsman was Claes Oldenburg, and the two of them commanded not only a breathtaking fluidity of line in their drawings but also an antic love of outrageous shifts in scale from the miniature to the monumental. With James Rosenquist, Venturi and Scott Brown shared an instinctive understanding of the visual power of commercial advertising, as well as his eye for arresting juxtapositions of incongruous but rhyming images. And their greatest Pop counterpart was Andy Warhol, who, like them, possessed a keen social insight beneath a seemingly insouciant surface sensibility that might be termed profound superficiality.

One of the consuming questions in architecture during the mid-twentieth century was whether or not what was once known as the building art could be reoriented from the technological preoccupations of the High Modernists and focused on more humane and aesthetic concerns. Venturi and Scott Brown, along with their teacher and employer Louis Kahn, did more to bring about this change than any of their peers, and the importance of what has, as a result of their all living there, been called the Philadelphia School, continues to influence the built environment in countless ways.