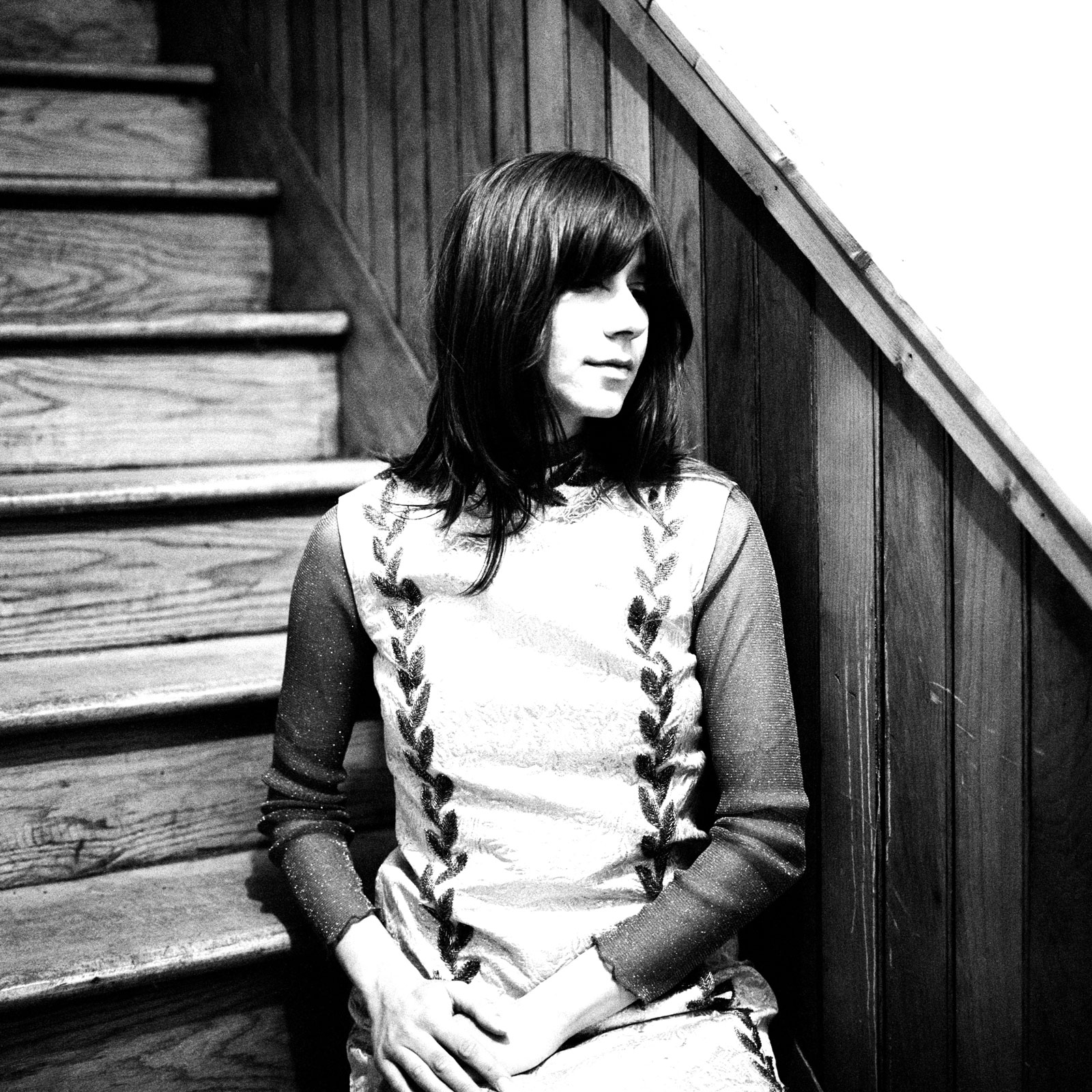

In the last ten years, Haley Fohr, a composer and vocalist who usually performs under the name Circuit des Yeux, has created an extraordinary musical language. Built around her haunting alto voice, which in its low register seems as though it should emanate from the tomb of an ancient mystic rather than from a woman in her late twenties with an active Instagram account, Fohr’s compositions have a disorienting, anachronistic-seeming power. Cloaked in a warm haze of analog tape and antique reverbs, her records sound like they could have been made at any point since the late 1960s. They share traits with psychedelia, the acoustic guitar patterns of folk music, and even the dirges of doom metal, and are impossible to place within any particular genre, style, or era.

In songs like “A Story of This World,” from her 2015 album In Plain Speech, the mellotron-like distorted flutes and fingerpicked guitars could be mistaken for Led Zeppelin; in other songs, such as “Paper Bag” from 2017’s Reaching for Indigo, a quasi-minimalist vocal pattern evokes the avant-garde composer and vocalist Meredith Monk. Despite Fohr’s sonic experimentation and her refusal to be locked into a particular style, it is her preternaturally deep voice that has most amazed listeners, inspiring comparisons to genre-defying male singers like Scott Walker and Tim Buckley, as well as female singers like Nina Simone and even Billie Holiday. Yet none of these analogies fully captures her restless artistry, so evident in her recordings and live performances, in which she constantly upends her listeners’ expectations, veering into shocking bouts of noise or deploying stunning new vocal techniques two or three octaves away from where she started.

“Songs” would seem an oversimplified term for Fohr’s creations, implying the preeminence of melody and lyrics. Her lyrics tend to suggest mental states or hint at stories, and while they can be powerfully resonant, the lyric never takes priority over the musical framework she builds around it. Fohr occasionally writes something that resembles an indie rock song with defined verses and choruses, such as “Fantasize the Scene,” but that song suddenly gives way to a surprise coda with a haunting string ensemble arrangement. Other songs contain melodies that never quite repeat, harmonic progressions that veer off course, and rhythmic shifts that call the basic perception of musical pulse into question. Fohr excels, in fact, at such manipulation of rhythmic patterns, sometimes played on acoustic instruments, sometimes generated through electronic means: murky, toy-like keyboards, glistening analog synthesizers, warbling tape echoes creating rich waves of distortion.

Reminiscent of Miles Davis’s controlled use of his trumpet, Fohr revels in the negative space created by the absence of her voice, letting the hypnotic layers of instrumental sound build tension and intensity. On the seven-minute-long track “A Story of This World,” after intoning the Benjamin Franklin-borrowed lyrics (“For the want of a nail…”), her voice drops out for almost three minutes, leaving woodwinds and strings to keep the psychedelic atmosphere flowing. When her voice reappears, it is transformed into a holler, then a yodel, then an otherworldly Yoko Ono-like ululation.

Fohr took on the name Circuit des Yeux while still a teenager in Indiana in 2008, when she began making gritty bedroom four-track cassette recordings and posting them on Bandcamp, a streaming website favored by underground artists. By 2010, she was touring and recording relentlessly. After making records for elite labels like Thrill Jockey (In Plain Speech) and Drag City (Reaching for Indigo), and expanding her touring around the globe, she has started to receive commissions from European cultural organizations. One of these, from the Leeds International Festival and Opera North in the UK, led to her performance of an original score for the 1923 silent film of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé at the Art Institute of Chicago on August 24.

The film of Wilde’s doom-laden biblical adaptation, directed by Charles Bryant and starring Alla Nazimova, can appear kitschy to a modern audience, rife as it is with stereotypes and melodramatic silent film acting. Fohr reimagines the movie as a framework for a modern multimedia performance. In Salomé’s story of a young woman whose beauty and talent are the catalyst for bloodshed, Fohr has created a nonverbal #MeToo-era meditation on femininity, desire, and power.

In interviews and in her own writing, sometimes through social media, Fohr has expressed a keen awareness of the fraught gender dynamics involved in being a female performer. She told the UK music magazine The Wire, “I often tour alone, and no one listens to you when you’re a young woman by yourself.” Some of her grim tour experiences have been documented in extremely intimate detail on her Twitter feed. Her determination to achieve autonomy in an art form and career in which women are often subjected to sexist stereotyping and outright harassment has parallels in Salomé. Men discuss a young woman and force her to perform for them; she expresses her desire for John the Baptist and she is killed. Fohr writes in a program note on her label’s website:

Advertisement

This is a story about a woman who is yearning to be heard, but is denied the road of truth. When I see Salomé’s need for John The Baptist I see a woman’s need to be heard, not desired. When I see Salomé dancing the seven veils—an action forced onto every woman at some point in her life—I see a woman utilizing the only tool at her means, the male gaze. When I see Salomé order the head of John The Baptist, I see a woman committing her own societal suicide through a powerful act of anarchy.

In her adaptation at the Art Institute of Chicago, Fohr transformed her usual musical approach. Her guitar was strikingly absent. Instead, she composed Salomé for a small ensemble of viola (Whitney Johnson), upright bass (Tyler Damon), and percussion (Andrew Scott Young), and stationed herself behind a table of electronic devices, which she used to loop her voice and further transform its pitch and timbre, trigger samples, and create feedback effects. Echoing the use of negative space on her records, she waited a long time before singing. The arrival of her voice, after a long opening of organ-like chords and string drones, had a mystical, almost cantorial intensity. With the silent film projected behind the musicians, Fohr showed exquisite control of her musical elements, carefully balancing the many colors of her voice, reserving its full force for the climactic moments of the film, like Salomé’s dance. Her heavily processed whispers, suggesting the muttering of John the Baptist in his cistern prison cell, were ghostly enough to transform the film into a horror movie.

Words were also powerfully absent from the piece, and not just from her lyrics. Fohr deleted the text from the intertitles of the film, leaving empty black spaces in their place. These black rectangles gave the film a broken rhythm that was reflected in Fohr’s use of silence in the music. The counterpoint of black visual interjections against the opening drone was another example of Fohr playing with tension through surprising rhythmic juxtapositions. Without even the introductory cards to provide expository information like names of characters, Fohr seemed to be pushing viewers toward ambiguous readings of the story, letting the characters define themselves wordlessly through facial expressions and actions.

Paced more like a play on a stage than a regular film, Salomé’s scenes run long, and frequently devolve into leisurely shots of Nazimova, her hair elaborately styled, swooning or pouting. Fohr dealt with the extended duration of the piece (roughly double the length of her albums) by breaking her music into long blocks of time. She transferred the repeating patterns she usually plays on guitar or synthesizer to the ensemble, often establishing an ostinato, or a texture, and letting it play at length with little variation. She alternated between ensemble sections and solo sections for her voice and electronics, saving the moments when she sang with the ensemble for high points—notably, Salomé’s dance of the seven veils, reaching a level of operatic vocal intensity that finally reflected the best-known musical adaptation of Salomé, that of Richard Strauss. Not even the accompanying images of King Herod’s orchestra of dwarves (a bizarre touch not found in Wilde’s play) could undercut it.

As the story reached its fatal dénouement, Fohr chanted the name “Salomé,” the only recognizable word she pronounced during the entire performance. A snare drum rang out a funereal pattern, and low feedback pulsed. These sounds continued for a few seconds past the end of the film, sustaining the violent energy of Salomé’s execution, as if venerating her doomed bid for artistic freedom and desire. In such moments, one could imagine Fohr following the path of composers like Mica Levi and Colin Stetson who, though working outside the Hollywood establishment, have composed acclaimed scores for films. But why should Haley Fohr necessarily follow their example? Her quest to determine her own fate has already made her an independent artist who possesses a remarkable voice together with a strong sense of its power to move, disturb, and astound listeners. As composer and as performer, she can go anywhere she desires with that voice.