Colour is strength, Strength is Life.

Only strong harmonies are important.—Emil Nolde

Edinburgh in Festival time. Street theater and jugglers, crowds streaming down Princes Street. A hint of autumn—“arctic air,” the weathermen call it—the gray city awash with light under pale blue skies.

These are the perfect conditions in which to see the radiant exhibition “Emile Nolde: Colour is Life,” at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. The building was once the city orphanage and the founder’s memorial claims he was followed to his grave by “100 wailing orphans”—somehow, you expect them to appear in the echoing corridors. The Nolde show, too, feels disconcerting, oddly haunted. How can one place this vital, revolutionary Danish-German artist, this great colorist whose paintings are so bold and sensual, yet who often was so virulently anti-Semitic, even joined the Nazi party, yet was subsequently banned as a painter making “degenerate art”?

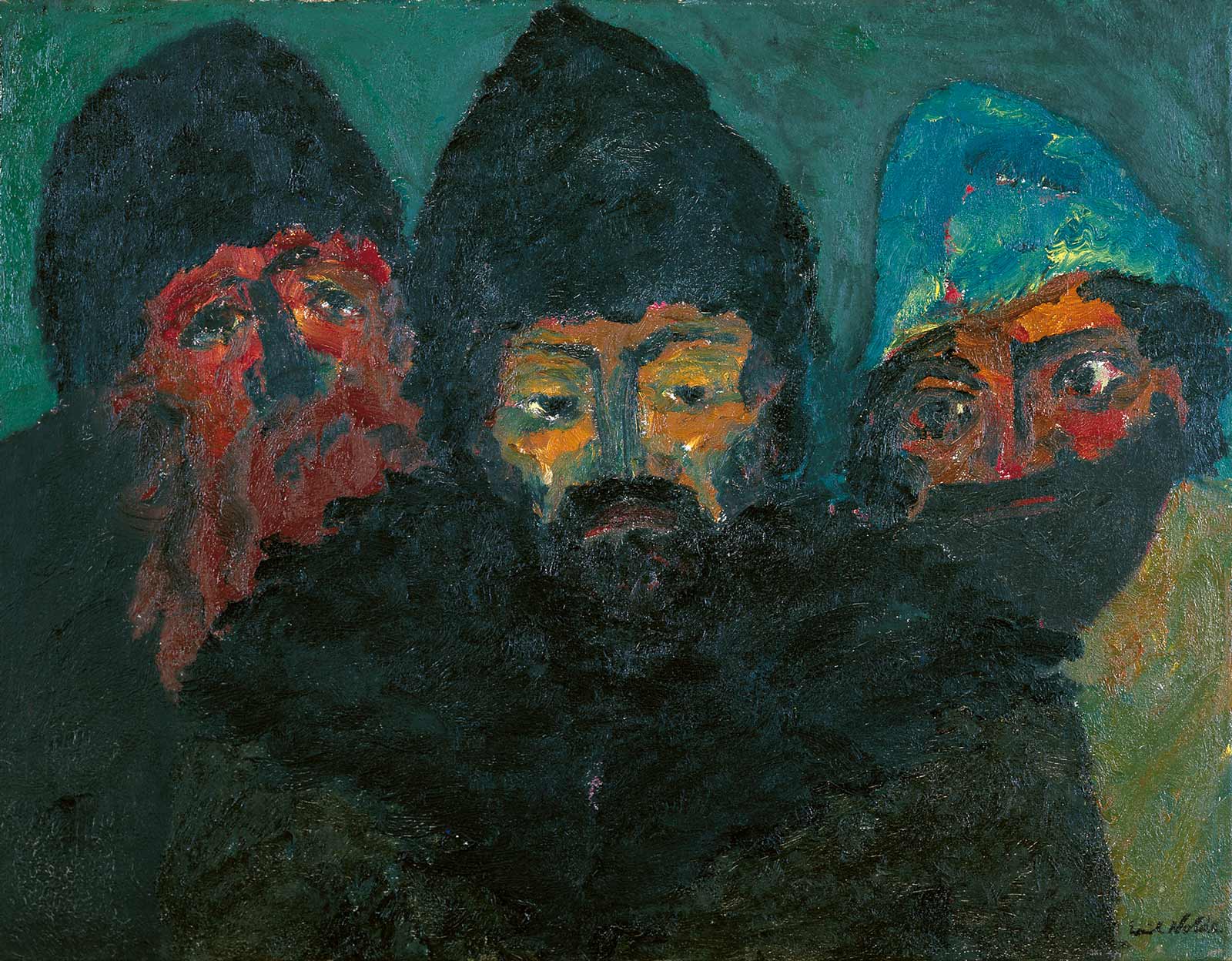

Profoundly influenced by Van Gogh and later by Munch, Emil Nolde (1867–1956) rejected Impressionism—which catches the external impression of a scene—in favor of Expressionism, which tries to convey the artist’s inner response, using exaggeration and distortion to delve into the nature of being. Yet Nolde seems to go even further, to be in love with the “expressiveness” of paint itself, its power to manipulate emotions, to delight, inflame, provoke. You can see this in two contrasting paintings from 1908. One is Market People, where a group of men with hunched backs and broad faces cluster around a tall, prophet-like speaker, perhaps a preacher, in a warm yellow robe. The second painting, Farmers, shows the same group, but the faces are wrenched, the shapes elongated, the preacher’s robe an acid green, changes that shift the mood from somber realism to something sinister and strange.

The farmers embody one enduring preoccupation of Nolde’s work: his native region of Schleswig, the flat, marshy lands just south of the Danish-German border. His father was German, his mother Danish, and in 1902, when he married the Danish Ada Vilstrup, he exchanged the family name of Hansen for that of the village where he grew up, a mark of his passionate identification with the soil. After World War I, when the area was ceded to Denmark, he took Danish citizenship, yet saw his art as German. In the second volume of his autobiography, Jahre der Kämpfe (Years of Struggle) he wrote that in the troubled times after the First World War, he was greatly exercised by “The question of what was German, what was Danish, occupied me during this restless time.… I loved my country and stood without envy or anger looking North and Southwards. Denmark had given me a much loved life partner, Germany the profound beauty of its music and fine art.” He was always on some border-line.

Later, he celebrated his homeland with lonely landscapes and tumultuous seascapes, like Ruffled Autumn Clouds (1927), in which sun pierces through dark clouds, and land merges with sea, the eternal, unchanging element. He painted milkmaids with their pails, villagers at the inn, family members and neighbors: in Farmer’s Sons (1915), two boys in their best suits, with cropped red-gold hair, stare out with piercing blue eyes. In Brother and Sister (1918), a couple with their heads close together suggest a mysteriously close alliance. In Blonde Girls (1918), the girls next door shimmer among the flowers: their pale beauty thrilled him, Nolde said, yet their slashed red lips hint at a certain hostility, a sense of danger—a disturbing, ugly detail that demands our attention, typical of his visceral, physical painting.

As a young man, Nolde worked as a woodcarver and furniture designer. He began painting seriously in his thirties, after visits to Paris and Munich, and in 1906 was invited to join the Dresden group “Die Brücke” (The Bridge), who admired his “tempests of color,” and whose aim, as stated in a woodcut manifesto, was to “call together all youth” and “to obtain freedom of movement and of life for ourselves, in opposition to older, well-established powers.” He stayed with these artists for only a year—he was always a loner, a free spirit. After a tumultuous spell with the avant-garde Berlin Secession, the progressive art group that had championed Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and a show with Kandinsky’s “Der Blaue Reiter” group in 1912, he worked alone.

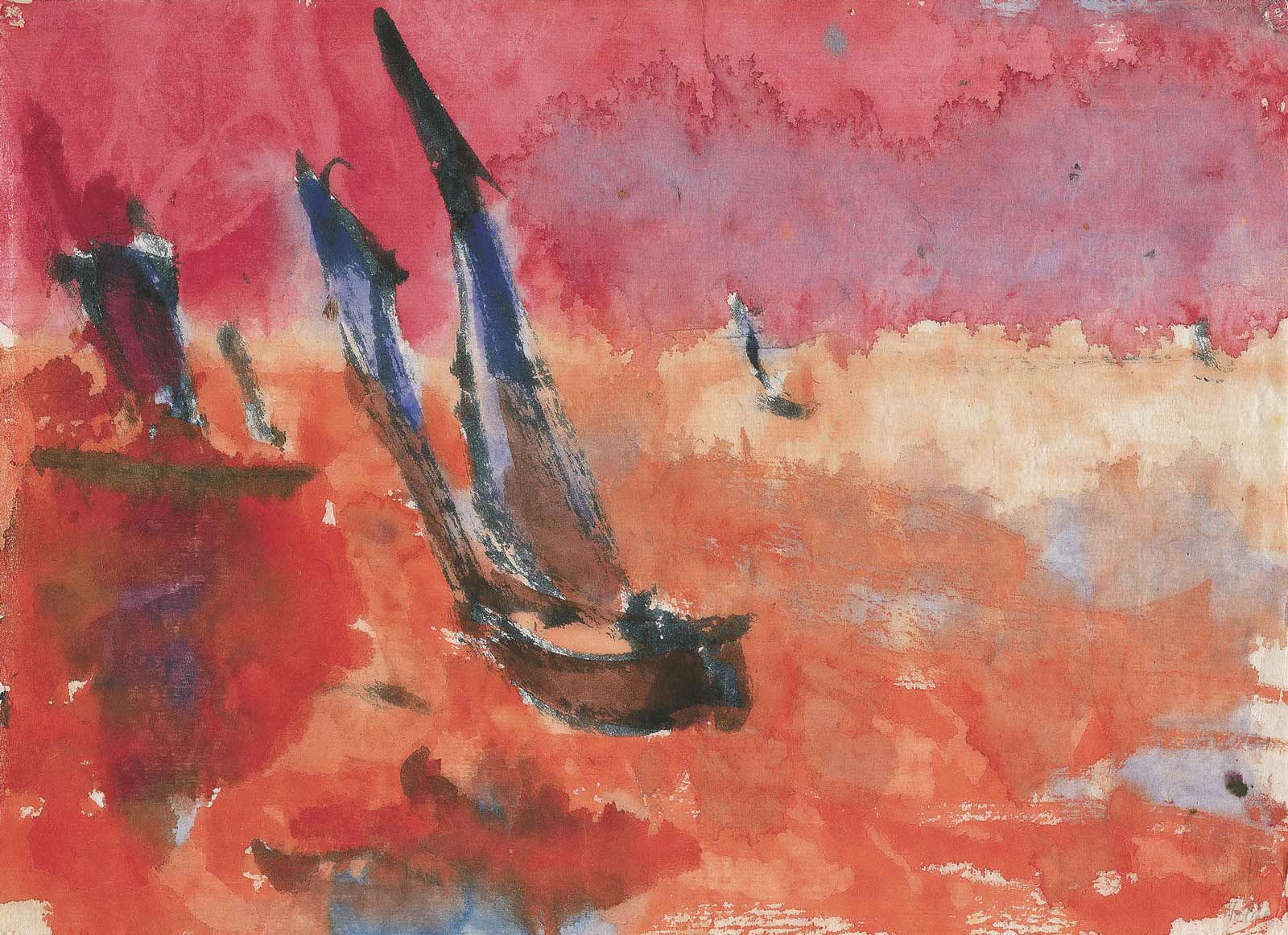

Nolde’s regional loyalty was related to his interest in cultural—and spiritual—identity, and his search for an elemental, primal way of life. A fierce critic of colonialism, profoundly interested in other races and cultures, he studied and drew at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, and in 1913 he and Ada joined an official trip across Russia and China to the South Seas. Enthralled, he wrote that he only had to raise his eyes from the paper to find “the richest, uproarious, flowing life.” His portraits and dreamlike sketches of boys swimming in clear water are full of admiration for the people’s dignity and grace—they may be patronizing in their Gauguin-esque idealism, but they are entirely free of the racism he showed toward the Jews in his own country.

Advertisement

The delicate side of Nolde’s art is found, too, in fluid sketches of Chinese junks, like Junk (in full sail) (1913), and in his etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts. With their rhythmic economy, the prints are in a different register from his oil paintings. It’s odd, in a show defined by the idea of color, to find so many evocative works in black and white, like the ink drawings and etchings of tugs in Hamburg harbor, magical flurries of lines, puffs of white smoke against dark posts and tall buildings. But in print-making, too, he used color to alter perception: he printed one lithograph, Young Couple (1913), in sixty-eight different color combinations, the mood shifting subtly with each variation.

Every winter, Nolde and Ada exchanged their sober Frisian life for Berlin. Nolde’s rapid, light watercolors and drawings of cabaret artists like Singer (in a green dress) (1910–1911), and his sketches of society women in elaborate hats, feel full of amusement and affection. But in his paintings, the cafés and theaters become lurid, lustful places, sites of decadence and corruption. In Candle Dancers (1912), the girls whirl in a red and purple out-of-body frenzy. In Slovenes (1911), a couple with exaggerated features stare glassily at the drinks before them. In Party (1911), two predatory men lean back to eye a woman wafting by.

Nolde’s paintings often seem to seethe with desire and conflict. The passionate urgency comes from the paint itself, from the broad brushstrokes, the gouging pallet knife, the thick layering of color that makes a work bewildering close up, yet dramatically formal from a distance, when the underlying structure and strongest lines become visible, springing out from the dense, swirling surface. This gives his religious paintings, in particular, a turbulent charge. Raised by a devout farming family, Nolde claimed that the Bible was the only book in his house growing up. In a catalogue essay, Keith Hartley quotes Nolde’s childhood memory of lying flat on his back in a cornfield, feeling that this was how Christ lay when he was taken down from the cross: “and then I turned over with a vague belief that the whole, wide, round, wonderful Earth was my beloved.”

In 1906, he painted himself as the Free Spirit, prophet and outsider, and in his later paintings, sacred and profane collide. In the erotic Ecstasy (1929), a woman lies naked, nipples taut and legs splayed beneath a blue crucifix held by a flame-haired figure. Is this Christ’s conception, as Nolde claimed, or a mystical, sexual vision? In Paradise Lost (1921), Adam and Eve are squat Primitive statues. But in Martyrdom II, painted in the same year, a pair of grotesque, gloating Jews laugh in front of the Crucifixion, their huge faces larger than the cross. This kind of crude blame for the death of Christ, stemming from the ferocious Lutheranism of Nolde’s background, helped to fuel the horror of the Holocaust.

In 1911, ten years before he painted Martyrdom, Nolde was outraged when the Berlin Secession rejected his religious paintings and blamed a critics’ conspiracy against innovative German artists led by the Secession’s president, Max Liebermann, and the influential dealer Paul Cassirer, both of whom were Jewish. In the 1920s and 1930s, he became an acclaimed painter and a member of the Prussian Academy, but anti-Semitism snakes through his writings, and his art. He joined the Nazi party in 1934, a move often explained in terms of his hope that Hitler would make Expressionism the national “German art.” In this, he was brutally mistaken. The mammoth exhibition of “Degenerate Art” in 1937, which showed works by Picasso, Mondrian, Chagall, Kandinsky, and Nolde’s friend Paul Klee, as well as German artists like Grosz and Kirchner, included over thirty of his works. Over a thousand were confiscated from galleries, more than any other artist. Nolde was appalled, remonstrating with Goebbels, “My art is German, strong, austere, profound… I have always given precedence to my belonging to Germany, actively fighting and confessing my loyalty to party and state at every opportunity.”

Nolde was banned from exhibiting and even from buying artist’s materials in 1941. In a curious way, this freed him: in his artistic banishment, he painted over a thousand small watercolors, what he called his “Unpainted Pictures.” In these fragile works on paper, rarely shown in public, mythical beasts rear up, grotesque figures embrace and dance, and flowers bloom in luminous glory. Creatures and faces, landscapes and skies are drenched in ravishing, intense color washes, wet-on-wet, staining the paper. Colors, Nolde wrote, “have a life of their own, crying and laughing, dream and joy, hot and holy, like love songs and sex, like hymns and chorales!”

Advertisement

In his last years, Nolde retreated to his Frisian homeland with his young wife Jolanthe, whom he’d married in 1948, two years after Ada died. Then in his eighties, he was returning to the land he had evoked so vividly in Landscape (North Friesland) (1920), in which dark clouds pile high, streaming over the red farmhouse and flat plains. We feel the lonely beauty, but also the threat, the darkness, and rage—the combination that makes Nolde’s work so powerfully raw and so unforgettable.

“Emil Nolde: Colour is Life” is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two) through October 21.