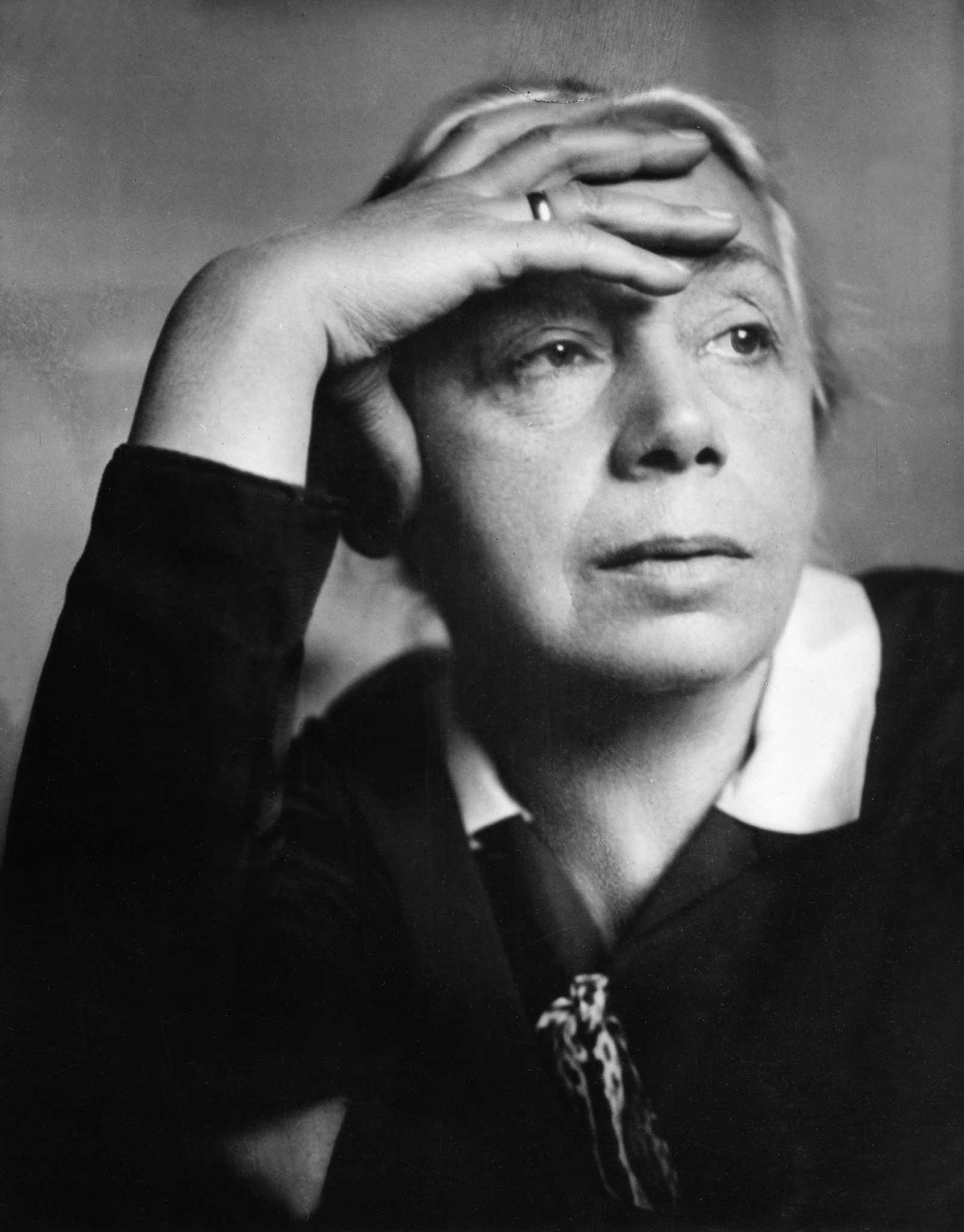

On November 9, 1918, extra editions of newspapers flood the center of Berlin. One of them, from the socialist Vorwärts, falls into the hands of Käthe Kollwitz as she is strolling in the Tiergarten. “The Kaiser has abdicated!” says the banner headline. At this point, the sculptor and graphic artist—the daughter of a bricklayer from Königsberg—is fifty-one years old and married to Dr. Karl Kollwitz. The two of them live in her home city, in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg. A round-faced woman with straight hair kept in a knot, she records her gloomy impressions in her diary.

As she reads the newspaper article, Kollwitz walks along the Siegesallee to the Brandenburg Gate, where thousands of people have gathered and are moving toward the neighboring Reichstag. The crowd is so thick that Kollwitz has no choice but to follow the flow. In front of the massive entrance to the Reichstag, which is crowned with the inscription “For the German people,” the crowd stops. A group of men can be seen on the balcony. “Scheidemann!” murmur those in front to those further back. Then thousands fall silent as the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann, now a minister without portfolio, begins to speak: “What is old and rotten has collapsed. Militarism is over!” He then makes a historic declaration: “We must ensure that the new German republic we will establish is equal to any threats. Long live the German republic!”

The cheering seems as though it will never end. When at last the masses do calm down, a soldier and a sailor speak from below the portal, followed by a young officer who tells the crowd, “Four years of war weren’t as bad as the struggle against prejudice and everything outdated.” The officer waves his cap and cries out: “Long live free Germany!”

Kollwitz lets herself be dragged along by the crowd to Unter den Linden boulevard, where red flags fly over the heads of demonstrators. Soldiers tear the cockades from their caps and throw them to the ground, laughing. “That’s the way it truly was,” Kollwitz writes in amazement. “You experience it, but you can’t really believe it.”

At that moment, her mind is filled with the image of her youngest son, Peter. He was just eighteen when he enthusiastically marched off to war in 1914. From the front, he sent letters full of heroic phrases that sounded as though they’d been copied from official military announcements. But then, a few weeks later, a black-rimmed envelope edged in black lay in her mailbox. It was as though a hole had opened in the ground and swallowed her. Today, on the founding day of the republic, Peter is again with her. “I think if he were alive, he would join in,” she writes. “He too would tear off his cockade. But he isn’t alive, and when I last saw him and he looked his best, he wore his cap with the cockade and his face was gleaming.”

Elsewhere in Berlin on that same day, a completely different new state is proclaimed. This time the speaker is the socialist Karl Liebknecht, and the setting is the Hohenzollerns’ Berlin Palace, “the very window where the Kaiser always spoke.” In contrast to Scheidemann, Liebknecht speaks of a radical socialist republic—not a “German” one. The two rival declarations reveal the dangerous tensions within the socialist movement, the schisms between the more moderate Social Democratic Party (SPD), the far more leftist Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), and the emerging revolutionary “Spartakusbund.”

The situation in the city is extremely precarious. Rifle shots regularly crack in the streets, machine-gun salvos rain down over squares, and even cannon fire can be heard. Over and over, crowds disperse in a panic only to regroup again, as if drawn together by magnets. The workers’ council formed by the revolution, it is said, is planning public executions to discourage looting.

On November 11, 1918, Käthe Kollwitz receives the “terrible news” of how the Compiègne negotiations have ended. That evening, as celebrations continue in Paris, New York and London, a “deathly silence” pervades the streets of Berlin. Fear begins to spread, and people stay home. Now and again, gunshots echo through the deserted streets.

*

In Berlin, rumors are going around that the former Kaiser Wilhelm has been murdered. Käthe Kollwitz hears them on November 12, 1918, as she is accompanying her friend Constance Harding-Krayl in her search for a job. At the post-revolutionary police directorate on Alexanderplatz, the two of them become acquainted with the bureaucratic labyrinth of the new regime, where no one knows anything, no one is accountable, and where everyone gets sent from one office to another without getting what they want.

Advertisement

When Kollwitz and her friend give up in frustration, a guard at the main entrance refuses to let them leave through the main entrance because they don’t have identity papers. They have to exit the building through a back door. Their description of the government offices evokes Heinrich Mann’s novel Man of Straw, which will appear for the first time in German in a couple of days. A Russian translation had been published as early as 1915.

The streetcar is completely packed as Kollwitz makes her way to her studio—these days, the train stations are jammed full of soldiers returning home. She’s heard that in the troop trains coming from the front, men have regularly been crushed to death. In the middle of the pushing and shoving on the streetcar, there’s an old woman with a crate containing a cat that meows softly. “The cat was spooked by gunshots and fled into my house,” the woman says. Now she, too, has had all she can take of gunshots and is fleeing to the countryside with the cat. The people around her laugh, amused.

Ever since the collapse of the old regime, Kollwitz has hoped that socialism would win the day, but now she is unable to ignore the realities of the situation. She thoroughly rejects how the communist Spartacus brigades are behaving and decides to keep her distance from them, in part because she realizes how resistant the general populace is to such a radically different social order. Employing violence in order to erect a socialist state against the will of the majority of Germans seems to her a contradiction in terms.

She tells herself to be patient, have faith in the democratic path of a constitutional convention, and hope that Germans will “gradually grow into socialism… although it’s somewhat disappointing when you think you can feel something and you’re told you’ll have to wait.” But will those “who can only stand to benefit if socialism is implemented” be prepared to wait? Or will they now try everything in their power to strike while the iron is hot?

The defeat of the army, the ignominious abdication of the Kaiser, and the end of the Reich have left a vacuum. In Germany and elsewhere, the forces of order that had previously held together governments and whole societies have weakened or collapsed completely. Revolutionary movements of various stripes are exploiting the new opportunities. Suddenly, it’s possible to call thousands of people to the streets or stand on a balcony and declare a new regime.

In Germany and elsewhere, many people wonder how it is possible to restore the stability of the old world while giving it a new foundation. The German Reich and several of the former member states of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires are on the verge of chaos. The great challenge in this situation is how to create a new, broadly recognized central authority and place in its charge the bureaucratic workings of the state, as well as the police and the military.

On November 20, along with thousands of other Berliners, Käthe Kollwitz squeezes herself into the main hall of Potsdam station. The train she and her husband, Karl, are so anxiously awaiting is late. When it finally arrives and the homecoming soldiers pour out of the carriage doors, the platform is cordoned off. Kollwitz climbs up some steps and scans the gray faces of the returnees with a hammering heart. At last, she spots Hans in the crowd. He sees her, too, and waves. Mother and son soon fall into one another’s arms.

Back at home, Hans’s seat at the table is decorated with flowers, and there’s wine with the meal. They drink to his return, to “Germany’s life and future,” and raise a glass as well to the memory of his brother, Peter, whose seat will remain forever empty. It’s strange how little pain there is now in remembering Peter, Kollwitz thinks. She used to believe the wounds would never heal. But that’s no longer true.

Should they unfurl the German flag from their window to greet the homecoming soldiers? And if so, which one? Kollwitz discusses the matter intensely with her husband. Ultimately, they decide on the red-white-and-black banner of the German Reich, the “dear German flag.” But they add a red streamer symbolizing the republic and a pine bough wreath for all “the ones who will never return.” Kollwitz is not alone in these sentiments. Many of her friends have also lost children.

*

You can feel the “terrible divisions today,” Kollwitz notes in her diary. There are daily mass protests, demonstrations and violence in Berlin. Even those crippled in the war are putting their wounds on public display and taking their demands to the streets, chanting: “We don’t want pity—we want justice!” The social democratic movement is about to split, and the Allies have refused to enter into peace negotiations or even deliver food to Germany until a democratically elected government is in place.

Advertisement

In her heart, Kollwitz supports the communist groups without whom the war would not have ended or the Kaiser been driven from power. Like the radical leftists, she hopes the revolution will continue rather than settle for the status quo. But her head knows that Germany is on the verge of breaking apart. “They will have to put down [the Spartacists] to get themselves out of this chaos, and to an extent they’re right to do that,” Kollwitz writes. It hurts her to think like this and to oppose those who risked being mowed down by machine guns to fight against war and hunger.

Christmas Eve brings tear gas and machine-gun fire to central Berlin. People are killed and wounded in both the army and the “people’s navy division,” which has holed up in the stables of Berlin Palace and taken a prominent Social Democrat named Otto Wels hostage. In the final days of the year, the Communists quit the council of people’s deputies, officially completing the schism within the Social Democratic Party. On December 29, the streets around Unter den Linden are packed as the Spartacists and the moderate socialists stage simultaneous demonstrations. Kollwitz loses sight of Hans in the crowd. It’s all she can do to extract herself from the aggressive pushing and shoving of the crowds.

On New Year’s Eve, Kollwitz takes stock. At least her family is reunited, and all of her loved ones who were spared by the war are in good health. “But peace is still not at hand,” she frets. “The peace will no doubt be very bad. Yes—there’s no more war. But you could say that, in its stead, we now have civil war.”

*

In early January 1919, the artist watches with growing concern as the conflict between the various revolutionary factions escalates. “Here in Berlin, there are strikes wherever you look,” Kollwitz notes in her diary. “The electric lighting is gone. It’s said that the water supply will be cut off because workers at the water company are on strike. We’ve filled our bathtub to the brim.” As the city infrastructure breaks down and people can no longer obtain basic necessities, far-leftist groups go on the offensive. They are determined at any cost to prevent the formation of a social democratic republic, and wish instead to impose a socialist republic of soviet-style councils.

On January 5, an agitated Hans returns from a demonstration, at the end of which, he reports breathlessly, the editorial offices of the mainstream socialist magazine Vorwärts were occupied. Material intended to influence opinion at the national convention was taken into the street and set on fire. The editorial offices of other social democratic and centrist publications have evidently also fallen into the hands of the revolutionaries. “There are no newspapers left except Freiheit and Rote Fahne,” he says, naming two radical leftist publications.

The Social Democratic government has to use special flyers to communicate with the populace and call upon Berliners to stage counter-demonstrations. On January 6, Käthe and Karl Kollwitz join masses of people who take to the streets in defense of the infant republic. They lose track of each other in the crowd. When an exhausted Karl finally returns home, he brings a shocking bit of news: “The government has no weapons.” They’ve all been confiscated, he adds. Yet that night, they can hear cannon fire. Who is shooting, if the government has no weapons, Kollwitz asks herself. And where is Hans?

Her remaining son comes back home late at night, excited, tired but unharmed. Thinking out loud, he wonders whether he should join the government’s troops. Kollwitz asks him if he means “with a weapon,” and he answers, “Yes.” That night, Karl ventures out into the city once more and sees people battling for control of the police directorate.

On January 11, news goes round that the offices of Vorwärts have been liberated. Kollwitz assumes that this is the work of government troops, but it soon becomes clear that other forces are at play. The government has freed Vorwärts with the help of the “Freikorps Potsdam,” an illegal militia of former frontline soldiers, who are using weapons they kept from the war—flame throwers, mortars, and machine guns—against the revolutionaries. That night, the police directorate is retaken.

Kollwitz is growing more tense: “I’m very downcast, even though I agreed that the Spartacists had to be put down. I have the uneasy feeling that it’s no coincidence these troops are being deployed and that the reactionaries are on the march. What’s more, the use of raw violence and the shooting of people who should be comrades are horrific.” In the days that follow, counterrevolutionary movements become increasingly visible. At an event at Zirkus Busch, the red-white-and-black Reich flag is unfurled, but without Kollwitz’s red streamer and pine boughs. Men sing “Hail to Thee in the Victory Wreath” and “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.” Some 150 people will ultimately lose their lives in the Spartacus uprising.

On January 16, just as the waves of violence seem spent, there is further shocking news. The leaders of the newly founded German Communist Party, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, have been murdered. For Kollwitz, this is a “dastardly, outrageous” act. Could the government be behind it, she asks herself?

It is scant consolation that the elections for the national assembly, against which the Spartacus uprising was aimed, do indeed take place a few days later. Kollwitz is among those who cast their ballots on January 19. It’s the first time in her life she’s been allowed to vote—the republic has instituted universal women’s suffrage. “I was so looking forward to this day, and now that it’s here, I feel a new indecision and halfheartedness,” Kollwitz writes. “I voted for the majority socialists… In my heart I’m further to the left.”

*

Liebknecht and thirty-one others are buried on January 25. Kollwitz has been asked by his family to make sketches of the hero of the German Left and proceeds to the morgue early that morning. “He was lying in state amidst the other coffins,” Kollwitz writes. “Red flowers were laid around his forehead with its gunshot wound, his face was proud and his mouth was open slightly and twisted in pain. His expression was somewhat surprised.” Meanwhile, people have gathered for a massive funeral procession in the city, beginning in the working-class district of Friedrichshain. Masses of people, too many to count, walk behind the coffin. Kollwitz stays at home working on her sketches, but Karl and various friends tell her about the great number of people who turned out, the pushing and shoving even at the open grave, and Liebknecht’s widow, who got so upset she fainted. They also relate how Freikorps militias kept a tight watch over the march all along the route.

“How small-minded and wrong all these measures are,” she writes. “Berlin, or at least a major part of it, wants to bury its dead. That’s not a revolutionary matter. Even between battles there are hours of calm, in which the dead are laid to rest. It is ignoble and outrageous to have soldiers and paramilitaries harass Liebknecht’s followers all the way to his grave. It is also a sign of the government’s weakness that it has to condone such harassment.” Still, Kollwitz must have known that the moderate republic she, too, favored would have been toppled had the Freikorps not intervened. In this sense, she, too, is a co-signatory to the pact that the new German republic has concluded with the devil.

February 6, 1919, would have seen Käthe Kollwitz’s son Peter turn twenty-three. That date and the memories she associates with it appeared in her dreams the night before. Now, on the day itself, Kollwitz takes out some sketches she made during the war for lithographic prints. In one, the artist depicts herself as a mother protecting her children, Hans and Peter, by embracing them in her arms. It’s a simple, almost spare image. As Kollwitz works away, the violence continues in the city, and more fathers and sons die.

*

Käthe Kollwitz is happy for the harbingers of spring in May 1919, but she’s dismayed by the harbingers of peace. “The swallows are back again!” she writes. “Returning from an art academy meeting, I walked down Unter den Linden… Everything was wonderful. The sky was full of light, the foliage was still delicate, and everything looked as if transfigured. I felt again that Berlin was my home, the city I love… And now we’re threatened with such a terrible peace. The palace still hasn’t been repaired. The balcony from which the Kaiser always spoke is shot half to smithereens, and the entrance badly damaged. A symbol of crushed majesty.”

The news from Versailles brings fresh unrest to Berlin, just as the city is beginning to settle back into its everyday routine. In May, masses of people are once again on the move on the streets of the city center. Public opinion is anything but unanimous. There are demonstrations for and against accepting the Allies’ terms of peace, and in a situation this divided and emotionally charged, confrontations are inevitable.

Kollwitz doesn’t take part in any of the public demonstrations. She’s too busy trying to capture the experience of the time in her art: loss, death, sadness, and starvation are her subjects. But she finds it incredibly difficult to work. She used to be able to concentrate for hours, becoming engrossed in her creations. Now she feels nervous and worried, and her works seem inadequate even before she has finished them.

On June 29, 1919, the newspapers announce that the new government has signed the peace treaty. How Kollwitz once longed for this day, and how bitter it now appears. “I thought about this day so often,” she writes. “Flags hanging from all the windows. I considered long and hard what kind of flag I would put out and concluded that it should be a white flag with big red letters spelling out: peace. Garlands and flowers were to dangle from its shaft and tip. I thought that it would be a peace of reconciliation, and that the day on which it was proclaimed would be a day of ‘sobbing recognition’ among people crying tears of joy that peace had arrived.” Kollwitz does, in fact, feel like crying, but not from joy.

Still, what option does she have other than to carry on? Her husband has to care for increasing numbers of patients, many of whom suffer more from general privation than from any specific illness. Kollwitz herself has commissions. Life must continue. She begins to clear out her dead son’s room, so that her mother, who’s suffering from dementia, can move in. “This is such sorrowful work,” she sighs. In a red cabinet, she finds Peter’s painting kit, his sketchbooks and examples of his keen mind, liveliness and talent. “His room was sacred,” Kollwitz writes. Now it will become profane.

In 1933, Käthe Kollwitz watches as the Nazis, who will later classify her art, too, as “decadent,” assume power. In 1940, her beloved husband Karl dies. A committed pacifist, Kollwitz suffers through World War II, but doesn’t live to see another peace. Having been bombed out of her apartment, she moves to the town of Moritzburg, near Dresden, where she dies on April 22, 1945, a few days before Nazi Germany’s capitulation.

This essay is adapted from The World on Edge: The End of the Great War and the Dawn of a New Age, published by Macmillan.