It came to be a core belief held by the American public and media that Barack Obama was a self-creation who had stepped out of nowhere. In a racially divided society, for some the idea that he belonged to no tribe made it possible to vote for him. For his detractors, of whom Trump and his birther movement were the most visible, the belief provided an opportunity to claim that Obama was not a true American. Indeed, he cut a solitary figure: parents and American grandparents dead, no full siblings; what else there was of his family lived in Kenya, which might as well have been the moon to many Americans. Marriage to Michelle gave Obama what he appeared to lack, a family and a community, though his Kenyan ancestry meant he was a member of the African-American community by adoption rather than birthright.

Against the backdrop of the fantasy of normality to which American (and not just American) popular culture subscribes—that is to say, the insistence that all but a few grow up in the same town and live there all their lives—Obama’s story appeared unusual. The truth is that his grandparents made the move to Hawaii (after several moves around the country), doing what millions of Americans before them have done and continue to do: searching for better opportunities. One result is that families become stretched over distance and time until the links between uncles, aunts, cousins, and generations are broken and reformed with new generations in new places.

Even so, the stand-out fact of Obama’s biography remained and remains that he had been born of a Kenyan father and a white mother. “No life could have been more the product of randomness than that of Barack Obama,” wrote David Maraniss in his 2012 biography of the former president. This, though, is the case only when his life is viewed from an American perspective. From an African perspective, the tradition of sending young men to study overseas, as was the case with Barack Obama Sr., is a familiar and longstanding one. In 1852, William Wells Brown, the American playwright, fugitive slave, and abolitionist, noted that he might meet half a dozen black students in an hour’s walk through central London. Some sixty years before that, in 1791, the Temne King Naimbana (of what became Sierra Leone in West Africa) sent his son John Frederick to England, for reasons of political expediency (he sent another to France, and a third to North Africa to acquire an Islamic education). Tragically, John Frederick never made it home, but died on the return passage.

In the second half of the twentieth century, geopolitical events—the end of empires, the rise of nationalism in African countries, the cold war, communism, and the second “red scare”—would see an exponential rise in the numbers of Africans sent to study overseas. So the meeting of Obama’s parents came about more as the unintended consequence of political policy than by random chance. For me, Obama’s story is remarkably familiar. My parents met under very similar circumstances. My father was born in 1935 in Sierra Leone; Barack Obama Sr. was born in Kenya in 1936. My mother was white and British; Obama’s mother was a white American. Both women met and married the men who would become our respective fathers when those men were selected to study at university abroad—a story Obama relates only briefly in his memoir Dreams from My Father:

My father grew up herding his father’s goats and attending the local school, set up by the British colonial administration, where he had shown great promise. He eventually won a scholarship to study in Nairobi; and then on the eve of Kenyan independence, he had been selected by Kenyan leaders and American sponsors to attend a university in the United States, joining the first wave of Africans to be sent forth to master Western technology and bring it back to forge an new, modern Africa.

Obama was wrong about one thing: his father was not in the first wave of students sent overseas to master Western technology, though he was in the first wave of Kenyans who were sent to America. Up until then, most African students had been destined for Britain and, starting after World War II, to the Soviet Bloc and China. In fact, the adventures of this generation of Africans would one day inspire a genre of literature, collectively known as the “been to” novels, exemplified by Ay Kwei Armah’s Fragments, No Longer at Ease by Chinua Achebe, and Ama Ata Aidoo’s Dilemma of a Ghost, fictions that told of the challenges both of leaving the motherland for the West and of return.

Advertisement

*

My father’s insistence that only a British boarding school was able to provide an education good enough for his children had me in tears at Freetown’s Lungi Airport three times a year as we waited to board the plane to London. My father was unyielding, reminding us constantly of the value of the enterprise we were undertaking and about which I didn’t care in the slightest. Paying for our education came before buying a house, before foreign travel, before everything. My father’s own story was both extraordinary and yet, in its own way, entirely typical of the changing times in which he was born. The son of a wealthy farmer and a regent chief from the north of Sierra Leone, Mohamed Forna had won a scholarship at an early age to Bo School, “the Eton of the Protectorate,” as it was known, many miles from home in the south of the country.

At the time, Sierra Leone was a British colony, though one that was never settled by whites, who, unable to tolerate the climate, died in such droves from malaria and tropical illnesses that the country was dubbed “the white man’s grave.” British fragility made a crucial difference to the style of governance Britain chose to adopt in West Africa. Instead of a full-fledged colonial government such as existed in Kenya, where the climate of the Highlands was suited to both coffee and Europeans, in Sierra Leone the guardians of empire relied instead on a system of “native administration.” Bo School was founded by the British for the sons of the local aristocracy, who, according to plan, would play a leading role in governing Sierra Leone on behalf of the British.

Generally, the British were cautious about allowing their colonial subjects much in the way of book-learning. The colonial project had begun with a great deal of hubris, talk of a civilizing mission and the belief that Britain could create the world in its own image. Education was a part of that mission. But by the time Lord Lugard, the colonial administrator and architect of native administration, became the governor of Nigeria in 1912, he was sounding warnings against “the Indian disease,” namely the creation, through education, of an intellectual class who would embrace nationalism. Burned by the threat of insurrection elsewhere in the Empire, though still intent on pursuit of an administration staffed by local talent, the British allowed a few Africans just enough education to create a core of black bureaucrats, but no more.

Sierra Leone’s beginnings were a little different from those of Britain’s other African holdings. In the late eighteenth century, British philanthropists had established settlements there of people freed from slavery, many of whom had fled from America to Britain following Lord Mansfield’s 1772 ruling that protected escaped slaves. As part of this social engineering experiment, schools and even a university were established in the capital, Freetown. Fourah Bay College, established in 1827, was the first institute of higher education built in West Africa since the demise of the Islamic universities in Timbuktu. Elsewhere in Britain’s African dominions, and in the early days of empire, most educational establishments were built by evangelically motivated Christian missionaries, and they were tolerated but not encouraged by the colonial administration.

In Kenya in the 1920s, precisely what Lugard feared began to happen: missionary-educated Kenyan men established their own churches and challenged white rule. The locals had a name for Western-educated Kenyans: Asomi. Harry Thuku, the father of Kenyan nationalism (whose story is narrated in Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s tale of the Mau Mau rebellion, A Grain of Wheat) was one such. In their churches, Asomi pastors accused the missionaries of distorting the Bible’s message to their own ends and preached an Africanized version of Christianity, and the Asomi founded associations to represent African interests and built their own schools in which pupils were imbued with a sense of patriotism and pride.

Still, whatever resistance Britain’s Colonial Office offered to the idea of the educated native, by the later days of empire, faced with ever-growing demands for colonial reform, the British began to build a limited number of government institutions, with the intention, in the words of the Conservative minister Oliver Stanley in 1943, of guiding “Colonial people along the road to self-government within the framework of the British Empire.” Any future form of self-governance was intended to create the basis for neocolonialism and a bulwark against the threat of communism.

Shifts in British attitudes, however, were soon outstripped by African ambitions. One million African men had fought on the Allied side during World War II, and those experiences had broadened their worldview. Many had learned to read and write—among them, Obama’s grandfather, Onyango, who, according to Obama family lore, traveled to Burma, Ceylon, the Middle East, and Europe as a British officer’s cook. Whether Onyango knew how to read and write English before he was recruited is unknown; it is possible, though unlikely. By the time he came back, however, he was able to teach his young son his letters before sending him to school. In Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama recounts Onyango’s surviving sister and his great aunt Dorsila’s memories of his grandfather: “For to [Onyango] knowledge was the source of all the white man’s power, and he wanted to make sure his son was as educated as any white man.”

Advertisement

Across the continent, emerging nationalist movements were gaining ground. For them, literacy followed by the creation of an elite class of professionals were the necessary first steps toward full independence. The courses on offer at the government colleges were restricted in subject and scope (syllabuses had to be approved by the colonial authorities) and the colleges themselves could admit only limited numbers of students. Energized and impatient, a new generation refused to wait or to play by the Englishman’s rules. With too few opportunities on the continent, they set their sights overseas, on Britain itself.

Few had the means to cover the costs of travel and fees. There were a limited number of scholarships available through the colonial governments, mainly to study subjects the local universities were not equipped to teach, such as medicine. A lucky few found wealthy patrons; others still were sponsored by donations from their extended families, and sometimes from entire villages. The Ghanaian nationalist and politician Joe Appiah, father of the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, ditched his job in Freetown without telling his employers and bought himself a one-way ticket on a ship bound for Liverpool, hoping to get by on his luck and wit.

*

My mother Maureen has a particular memory of my father. On April 27, 1961, the day Sierra Leone became a self-governing nation, he got roaring drunk at a sherry party held by African students at the premises of the British Council in Aberdeen. The couple had married at the registry office in Aberdeen one month before, in a ceremony attended by their friends among the West African students. On the way home, on the top deck of the bus, my father lit six cigarettes and puffed on them all at once. “But Mohamed, you don’t even smoke,” my mother had protested. And my father replied: “I’m smoking the smoke of freedom, man. I’m smoking the smoke of freedom.”

In the decades between the two world wars, Britain emerged as “the locus of resistance to empire” where anti-colonial movements were shaped by the growth of Pan-Africanist ideals among artists, intellectuals, students, and activists from the colonies. The Kenyan writer and activist Ngũgĩ wa’ Thiong’o, commenting on his arrival in Leeds in 1964, remarked to me:

For the first time I was able to look back at Kenya and Africa, from outside Kenya. Many of the things that were happening in Africa at that time, independence and all that, were not clear to me when I was in Kenya but made sense when I was in Leeds meeting other students from Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, students from Australia, every part of the Commonwealth, students from Bulgaria, Greece, Iraq, Afghanistan—we all met there in Leeds, we had encounters with Marx with Lenin, and all that began to clarify for me a change of perspective.

Among those elites who gathered there, driven by, and driving, the desire for self-rule, were Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Michael Manley, Marcus Garvey, C.L.R. James, Seretse Khama, Julius Nyerere, as well as a number of African Americans, including Paul and Eslanda Goode Robeson. In London, anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist ideas were shared and enlarged, spurred by a shared experience as colonial subjects in their homelands and as the victims of racism and the color bar in Britain. “They were brought together too by the fact that the British—those who helped and those who hindered—saw them all as Africans, first of all,” writes Anthony Appiah. And so those who may previously never have identified themselves as such began to do so and explore the commonalities of race, racism, and nationalism. And out of those conversations arose new political possibilities involving international organizations and the opportunity for cultural exchange.

Arrival in Britain brought with it many shocks for the colonial student. Whereas before they were Sierra Leonian and Temne, Luo and Kenyan, Hausa and Nigerian, suddenly they were simply black, subject to all the attitudes and reactions conferred by their skin color. Signs declaring “No Irish, No Dogs, No Blacks” were still common on rental properties during my father’s time in Scotland. My mother told me of the insults my father endured in the street—directed at her as well, when they were together. Later, my father’s second wife—my stepmother, who also went to university in Aberdeen and vacationed in London, staying in the apartments of other African students—recalled the gangs of racist skinheads who arrived to break up their gatherings. “Somebody would run and call for the West Indians,” she told me, their Caribbean neighbors being more experienced in fending off such attacks. In a reversal of the immigrant dream story, Sam Selvon’s 1956 novel The Lonely Londoners tells the story of black people arriving in the 1950s in search of prosperity and a new life, only to discover cruelty and misery.

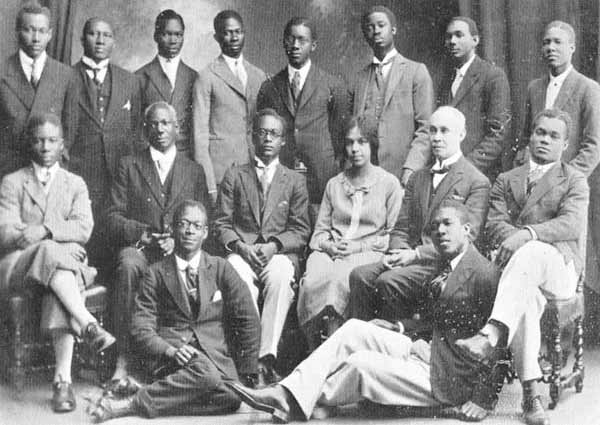

In order to confront the challenges of their new lives, as well as to keep abreast of political developments back home, the colonial students organized themselves into societies and associations. One such was the hugely influential West African Students’ Union, or WASU. If London was the heart of resistance, then WASU was its circulatory system. My father and his friends were all WASU members, as was every former student of that time from a West African country to whom I have ever spoken. WASU was the center of their social, cultural, and, especially, political life. It also “functioned as a training ground for leaders of the West African nationalist movement,” wrote the historian Peter Fryer; indeed, both Kwame Nkrumah and Joe Appiah were among the leading names who served on WASU’s executive committee.

Unnerved at the pace with which calls for independence were gathering, the Colonial Office kept a close eye on the students’ activities. In London, the department funded two student hostels, which aided the many students whom the color bar prevented from finding decent lodging (and also kept the students conveniently in one location). The civil servants also spied on the African students through MI5. A tug-of-war was taking place within the Colonial Office: on one side were the “softly-softlies” who favored an approach designed to promote good relations with the future leaders; on the other were the hardliners concerned that Communist ideas might take root among the rising generation. Such was the fear of Communist-inspired insurrection in West Africa that Marxist literature was banned and travel to Eastern European countries restricted in those countries.

The colonial administrator Lord Milverton once described WASU as “a communist medium for the contact of communists with West Africans” through the Communist Party of Great Britain. Then-parliamentarian David Rees Williams even accused the Communist Party of using prostitutes to spread its message and called for restrictions on the numbers of students entering the country from the colonies. Though MI5 did not go so far as to keep individual files on all the students, they did do so for the most visible leaders like Nkrumah, whose phone they tapped.

Certainly, there were Marxist sympathizers among the WASU leadership and the African student body in general. Ngũgĩ wa’ Thiong’o talked to me about his road to Marxism, which began during his student years in Leeds, when he saw poor whites for the first time and witnessed, during the student demonstrations in Leeds, white policemen turning on their own, a “vicious crushing of dissent.” Julius Nyerere turned to socialism during his time in Edinburgh, returning to Tanzania in 1952 to become a union organizer and later the first president of a new, socialist republic.

By the 1960s, with the colonies gaining independence one by one, and China and the Soviet bloc beginning to offer their own scholarships, the softly-softly approach had prevailed within Britain’s Colonial Office. The administration of the students’ affairs was handed over to the British Council, which began a diplomatic charm offensive. Before they even left home, students on government scholarships were offered induction seminars on what to wear and how to conduct themselves in the homes of British people, and shown films on how to navigate the challenges of daily life. In one of these films, entitled Lost in the Countryside, a pair of Africans abroad (dressed in tweeds, they emerge from behind a haystack) are instructed firmly: “Do not panic! Find a road. Locate a bus-stop. Join the queue [and there in the middle of nowhere is a line of people]. A bus will arrive. Board it and return to town.” Once the students were in the UK, the British Council arranged home-stays for those Africans who wanted an up-close experience of the British (some 9,500 said they did). My stepmother recalls being advised never to sit in the chair of the head of household, a faux pas of which she has retained a dread all her life.

And finally, there were social events at the Council’s premises in various British cities. At a Christmas dance in the winter of 1959, my father, a third-year medical student at Aberdeen University, approached a young woman, a volunteer named Maureen who was helping to pour drinks for the party, put out his hand and said: “I’m Mohamed.”

*

If the attitude of the British authorities toward the West Africans was one of wavering welcome, the attitude toward the East Africans, Kenyans in particular, was even more complicated. In 1945, there were about 1,000 colonial students in Britain, two thirds of whom came from West Africa and only sixty-five of whom came from East Africa. In Kenya, a simmering mood of rebellion had by the 1950s given rise to the Mau Mau, a movement that explicitly rejected white rule and gave voice to the resentment against colonial government taxes, low wages, and the miserable living conditions endured by many Kenyans. The Mau Mau, which found its support mainly among the Kikuyu people who had been displaced from their lands by white farmers, demanded political representation and the return of land. Facing armed insurrection, in 1952 the British declared a state of emergency, and tried and imprisoned the nationalist leader (who would later become the first president of Kenya) Jomo Kenyatta, who had returned to his homeland from London in 1947.

Upon Kenyatta’s imprisonment, Kenyan nationalists turned to the United States for support. The activist Tom Mboya, a rising political star who in 1960 featured on Time magazine’s cover as the face of the new Africa, became the strongest voice calling for independence in Kenyatta’s absence. In 1959, Mboya began working with African-American organizations—in particular, the historically black private and state colleges, as well as civil rights champions such as Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Jackie Robinson, and Martin Luther King Jr.—and toured the United States talking about black civil rights and African nationalism as two sides of the same coin. His aim was to raise money for a scholarship program to bring Kenyan students to the US. Over two months, Mboya gave a hundred speeches and met with then Vice President Richard Nixon at the White House. By that point, independence for Kenya was a matter of when, not if—after all, Ghana had already attained independence—and it looked very much as though Britain was deliberately refusing Kenyans the help they needed to prepare for self-governance.

So here was Mboya offering the United States a foothold of influence in Africa, which Britain, even against the backdrop of a cold war scramble for the allegiance of African nations, was too churlish or too arrogant to secure. Although Nixon stopped short of agreeing to meet Mboya’s request for help, the Democratic candidate for the 1960 presidential election John F. Kennedy did do so, and his family’s foundation donated $100,000 to what became known as the “African student airlifts,” the first of which had taken place in 1957.

Mboya was a member of the Luo people, a friend of Onyanga’s, and sometime mentor to his son, Barack Obama Sr. On his own initiative, Obama Sr. had managed to secure himself an offer from the University of Hawaii, and this won him a place on a later airlift in 1959. Here was a young man with an excellent brain, and here, too, was a new dawn on the horizon bringing with it a new country—Obama Sr. saw himself as part of it all. The writer Wole Soyinka, who himself studied at Leeds, England, in the 1950s, had a name for them, the young men and women who came of age at the same time as their countries; he called them the “Renaissance Generation.”

Just as the West African students bound for Britain had been coached in what to expect, so the Kenyans were briefed on arrival in the United States, including about the prevailing racial attitudes they should expect to encounter there. The world-renowned anthropologist and now director of the Makarere Institute of Research Mahmood Mamdani, who traveled to the US on a 1963 Kenyan airlift, recalls being told it would be “preferable for us to wear African clothing when going into the surrounding communities because then people would know we were African and we would be dealt with respectfully.” Under colonial rule, Kenyans certainly did not share the privileges of whites; even so, for many African students the daily indignities of racial segregation in America came as a shock. At least one was arrested for trying to buy a sandwich at a whites-only lunch counter, and some of those studying at universities in the South were prompted by their experience of Southern racism to ask to be transferred to Northern colleges. As had been the case for their counterparts in Britain, a close eye was kept on their activities. Returning from a trip to Montgomery, Alabama, Mamdani got a visit from FBI agents; he recalls that they asked if he liked Marx, to which Mamdani replied in perfect innocence that he had never met the man. Informed that Marx was dead, he replied: “Oh no! What happened?” And as he told me in our conversation many years later: “The abiding outcome of that visit was that I went to the library to look up Marx.”

Obama Sr.’s choice of the University of Hawaii was, in many ways, an unfortunate one. Hawaii was more cosmopolitan than other parts of the United States and he did at least escape some of the racist attitudes that confronted other African students, but he was far from all the debates, meetings, lobbying, and activism about independence that were taking place at the universities and historically black colleges on the mainland. When the opportunity arose, he chose to continue his studies at Harvard—and part of the reason was undoubtedly that he wanted to get closer to the action. In 1961, Kenyatta was released from jail; two years later, Kenya declared independence. When all that happened, Obama was still a long way from home—just as my father was when Sierra Leone won its independence.

In time, Ngũgĩ would return from Leeds, and Mamdani from the United States. Ngũgĩ was by then a published author, having abandoned his studies to write Weep Not, Child. Mamdani went on to teach at Makarere University, which became the venue for the famous 1962 African Writers’ Conference, and he helped to transform it from a colonial technical college into a vibrant university. One of the few women on the airlift, Wangari Maathai, flew back home from Pittsburgh in 1966, later to found the Green Belt Movement, an initiative focusing on environmental conservation that today is credited with planting fifty one million trees in Kenya and for which Maathai would be awarded a Nobel Peace prize. Still, for Kenya, as for every one of the new African nations, independence proved a steep and rocky road. Five hundred students who had earned their degrees overseas returned home, a significant proportion of them the American-educated Asomi. They would become the educators, administrators, accountants, lawyers, doctors, judges, and businessmen in the new Kenya. Despite the best efforts of Tom Mboya and his supporters, Kenya had only a fraction of the college-educated young professionals it needed.

*

Eight years after he had left Sierra Leone, my father returned. His elder brother had died and his family wrote that Mohamed was needed at home. By then, he was a qualified medical doctor, with a wife and three children. The year before, Obama Sr. had also returned home after the US government declined to renew his visa. Medical students and those who went on to higher degrees, especially, had found themselves away for long periods, as much as a decade. Unsurprisingly, in that time, many of the men had formed romantic attachments with local women. If those relationships were frowned upon in Britain, they were illegal in much of America. Loving v. Virginia, the case before the Supreme Court that finally overturned the ban on interracial unions, was not decided until 1967. When the Immigration and Naturalization Service declined Obama Sr.’s request to remain in the country, his relations with women were reported to be part of the problem. Already, he had fathered one child with Ann Dunham, a son also named Barack, but that marriage was over, and he had formed a new relationship with another white woman, Ruth Baker.

In Britain, the authorities, though they did not encourage such unions, did not intervene except, notably, in the case of Seretse Khama, heir to the Bangwato chieftaincy in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and Ruth Williams. This was at the behest of white-ruled South Africa, whose government would not tolerate an interracial marriage within its borders. Jomo Kenyatta had a child, Peter, with his British wife. I used to pass Peter in the corridors of the BBC, where for a time we both worked; he was in management, while I was a junior reporter awed by the prestige of his last name. The marriage of Joe Appiah to Peggy Cripps, the daughter of the Labour politician Sir Stafford Cripps, was one of the most high-profile unions of the day that also happened to be a mixed marriage.

Of Ann Dunham, first wife to Obama Sr. and mother of the future president, a childhood friend would later say: “She just became really, really interested in the world. Not afraid of newness or difference. She was afraid of smallness.” The same could be said of my mother, Maureen Christison. Aberdeen was simply too small for her. The African students represented a world beyond the gray waters of the North Sea. In the Scottish writer Jackie Kay’s Red Dust, her 2010 memoir of her search for her Nigerian father who studied in Scotland in the 1950s, her father overturns conventional wisdom in remarking how popular the male African students were with the local girls. The men frequently came from aristocratic families—both Appiah and Khama were royal, and my father was the son of a regent chief and landowner. “You must remember,” a contemporary of my parents observed during the time when I was researching my own memoir of my father, “they were the chosen ones.”

In 2017, in a New York Times op-ed assessing President Obama’s foreign policy legacy, Adam Shatz noted that Obama was “A well-traveled cosmopolitan… seemingly at home wherever he planted his feet. His vision of international diplomacy stressed the virtues of candid dialogue, mutual respect and bridge building.” Obama’s cosmopolitanism was rooted in several places: the fact of his Kenyan father (though not his immediate influence, since Obama Sr. was gone from the family before Obama was old enough to remember him), and later his painstaking search to assemble the pieces of his birthright, would do much to extend his vision. But before all of that, it was his mother, Ann, who instilled in him the foundations of his internationalism. She rehearsed for her son the version of his father’s story that Obama Sr. told of himself: that of the idealist devoted to building a new Kenya—albeit that in reality he was an unreliable husband and father, whose career came well short of his own expectations. It was Ann who remained true to that vision of a new world, who easily made friends with people of different nationalities, who subsequently married an Indonesian, and took her son to Indonesia to spend a formative period of his childhood, where she spent many years running development projects. My mother Maureen never returned to Scotland after the break-up of her marriage to my father. She married again, to a New Zealander who worked for the United Nations, and spent her life moving around the world, in time building her own international career within the UN.

Both women entered an international professional class, a group that the British historian David Goodhart disparagingly describes as the “anywheres”: people whose sense of self is not rooted in a single place or readymade local identity. If Obama’s search in Dreams from My Father was a quest for his African identity, it was also, and conversely, an attempt to discover whether he could ever be a “somewhere,” whether that somewhere was a place (in time, he would choose Chicago) or a people, part of an African-American community.

His next book, The Audacity of Hope, became, by contrast, a plea for complexity. Of his extended family of Indonesians, white Americans, Africans, and Chinese—in which I find a mirror for mine: African, European, Iranian, New World, and Chinese—Obama writes: “I’ve never had the option of restricting my loyalties on the basis of race or measuring my worth on the basis of tribe.” Obama knew and understood that he had more than one identity, that all of us do. Anthony Appiah credits his own avowed cosmopolitanism to his father Joe’s relaxed way with people from different worlds. I believe my father thought that his children would grow up to be both Sierra Leonian and British, a new kind of citizen, a new African, comfortable with our place in the world.

For all the hope, there were bitter disappointments as well. Shortly after Obama Sr. returned to Kenya, his mentor Tom Mboya was assassinated. Obama Sr. would lose himself to drink and die in a car crash. My father arrived back in Sierra Leone to a government openly talking of introducing a one-party system, a threat to his democratic ideals. As politically opportunistic leaders across the continent quickly realized how easily the newborn institutions of democracy could be subverted to personal gain, the returning graduates would find themselves forced to confront the very governments they had come home to serve. In Ghana, Joe Appiah was jailed by his former good friend Nkrumah; Ngũgĩ wa’ Thiong’o would be imprisoned for sedition against the Kenyan government and then exiled; in Nigeria, Soyinka encountered a similar fate. My father was jailed and killed. Many would pay a high price for the privilege of having traveled beyond Africa, for coming of age at the same time as their countries, for working and dreaming of a Renaissance yet to come.

How many times in my own travels in this world have I come across one of them, the chosen, of my father’s generation? There’s a quality of character they wear, whose origins I have come to understand. They carry, alongside a worldly ease, a sense of duty, of obligation and responsibility, that imbues all they say and do. Unlike the generations that followed, they never saw their own future beyond Africa. I try to imagine an Africa if they had never been, and I cannot. There are those the world over who decry the failings and weaknesses of the post-independence African states at the same time as many in the West—after Afghanistan, after Iraq, and facing assaults on their own democratic institutions—have slowly come to the realization that nation-building is no simple task, that democracy takes more than a parliament building. The generation of Africans to whom the task fell of creating new countries knew, or came to know, that alongside the desires and dreams, and the promise of a new-found freedom, they had been set up to fail. Their real courage lay in the fact that they did not surrender, that they tried to do what they had promised themselves and their countries they would. They went forward anyway.