When I was about ten or eleven years old, it was common at my boys’ school to make a loose fist, insert one’s nose into the hole it made, while stroking the top of it with the index finger and, at the same time, make a kind of “groo, groo” sound with heavily rolled “r.” The occasion for doing this was when a request for the loan of something like an eraser, sweet, or small amount of money was refused. What it signified was that the potential lender was mean, stingy, and, by implication, “Jewish.”

This would be in the mid-1970s. The school was in Hampstead, London, at the time not quite the haven for the tasteful ultra-rich it has become, but still mostly affluent, with a heavy tinge of liberalism in the air. One of the peculiarities of the area was the number of psychiatrists and psychoanalysts who lived or practiced there: Freud’s house in Maresfield Gardens (now a museum) was around the corner, as was the Tavistock Centre, training ground for generations of shrinks. The population, then, of bien-pensant intellectuals could have been transplanted to Manhattan without feeling discombobulated. And yet.

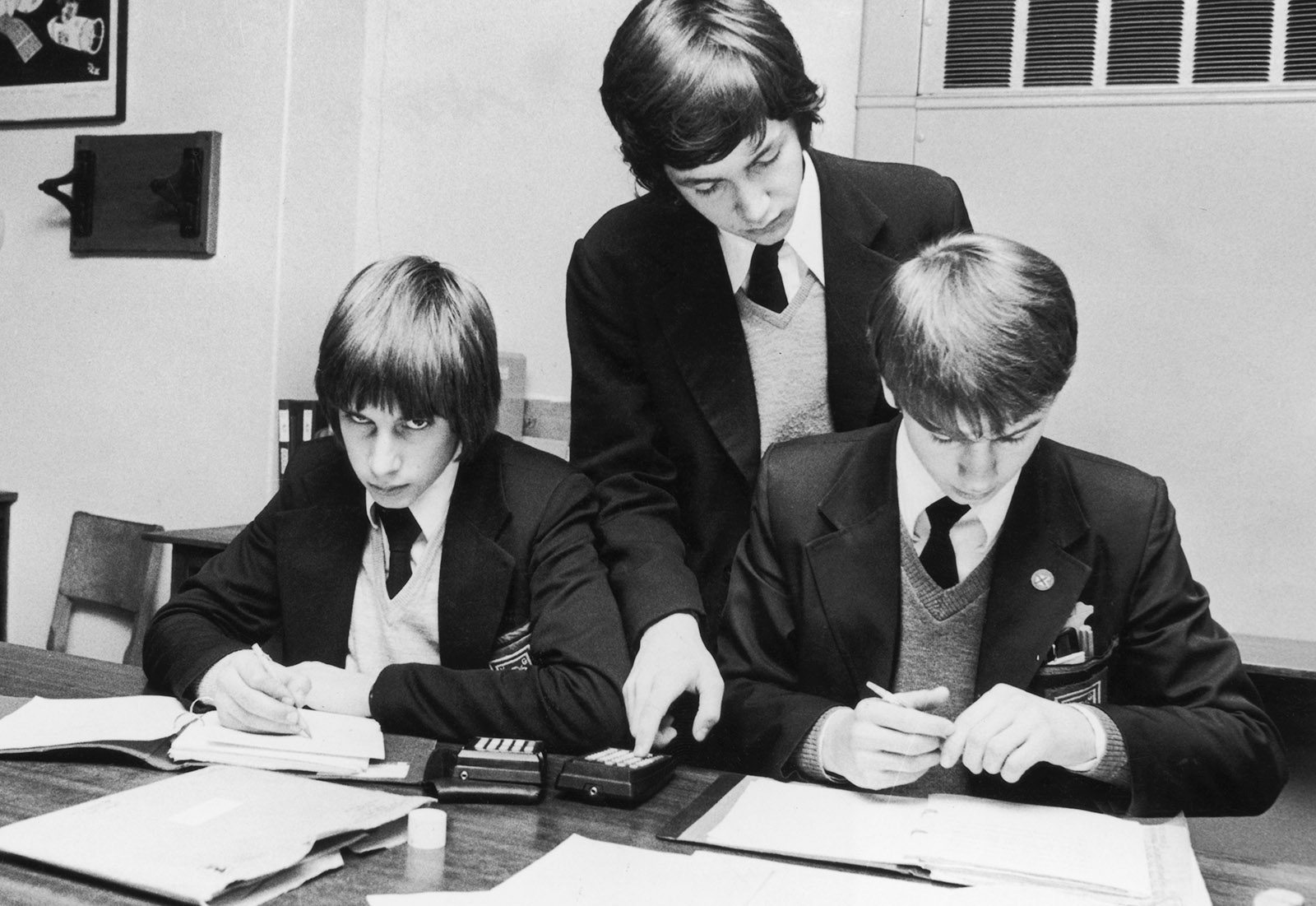

The school I went to was called The Hall, and competed with Arnold House, a mile to the south, to be the best preparatory school in the area. The Hall and Arnold House were private. Current fees for pupils, who can start at the age of four, are around £6,500 a term for day attendance. What they were when I started in 1968, when I was five, I don’t know. The school, founded in 1889, was big on tradition: its uniform is unchanged from when I was there, with its blazer—deep pink with black piping and a Maltese Cross (not actually a Maltese Cross, but that’s what we called it) on the breast pocket—making us, we felt, an obvious target for children from less privileged backgrounds.

For we were indeed privileged: the sons of businessmen, senior doctors, politicians, and peers. Among our number, in my class alone, were the son of the Liberal MP John Pardoe (his first name I do not remember, for pupils at this kind of school always addressed one another by their last names), and two peers’ children, whose first names I can remember for they were both memorably, if in different ways, horrible: Brer Ruthven (yes, “Brer”), the son of the future Tory arts minister “Grey” Gowrie, and Robin Russell, the second son of the Marquess of Tavistock, owner of Woburn Abbey and most of Bloomsbury. At the age of thirteen, the more able would take exams from our forcing houses for the grand destinies of Eton, Westminster, and Winchester. The Hall’s motto was Hinc in Altiora, “from here to higher things.” We were an elite, we were told, and believed it.

My time there was miserable. It left me with a feeling that marks me to this day, some four decades later: that I would never really fit in. Maybe this was because I had detected something bogus about the Establishment—or, more likely, it had detected something bogus about me, something alien, something Not Quite British. My mother was American, and when we went on holidays, I traveled on an American passport. The more obvious indicator, though, was my surname. Based on it, my nickname won’t be difficult to work out, the reptilian attendant characteristics—green, slimy—used as secondary ammunition.

When we were about eleven years old, we were handed by our well-meaning Religious Studies teacher a book called, if I remember correctly, Things That Matter (not to be confused with the book with that name by Charles Krauthammer). This differed from all our other textbooks in that it dealt with contemporary, or recently historical, socio-political matters, and it contained photographs, extremely rare for textbooks of the time. Its main purpose seemed to be to inform us of the evil potential of human nature. So, from then on, we became Holocaust-aware.

And it was around the same time that those playground taunts about Jewishness—that “groo, groo” gesture and talk of hoarding “shekels”—changed their tone. This caricature, so crude as to seem medieval, disappeared from the scene, to be replaced by something more nuanced, but perhaps more sinister. One of the things about The Hall was that many of its pupils were of Jewish ancestry; yet even Jewish pupils were not necessarily above using this taunt. After we fed on the fascinating horrors of the camps in Things That Matter, a certain calculation began to creep in: Who among us was Jewish, or Jewish enough?

I can recall the exact spot on the playground where the exchange occurred: in response to a question about my Jewishness, I answered, “I’m not Jewish,” to which came the retort, “Well, you’re good enough for the ovens.”

Advertisement

Technically, according to the Nuremberg Laws, my interlocutor was incorrect. Mischlinge zweiten Grades, or one-quarter-Jewish, would in 1935 have made me still eligible for German citizenship—though it would have been an uncomfortable time, I suspect. However, I was not Jewish, and although I knew there was Jewishness in my ancestry, I had never considered the question until then. I was raised in the milk-water, lukewarm embrace of the Church of England. I went to Sunday School as a child and colored in pictures of Jesus and lambs. (My parents were not religious at all.)

Yet, I came to realize, I looked Jewish. Or, if not Jewish, very much Not English. I had dark hair, dark brown eyes, thick lips, a larger than average nose, and, though this was common at the time for gentile and Jew, I was circumcised. (In communal showers, we all got a good look at each others’ cocks.) I was also one of the smallest in class, obviously happier with a book than a football—in fact, never more wretched than on a playing field in winter.

And then there was the name. It is, and there was no getting around this, a Jewish name. (These days, people often assume, until corrected, that I am called “Lazard,” as in Lazard Frères, the banking firm established in the mid-nineteenth century by three French-Jewish brothers; this is a problem in itself for it involves a presumption of great wealth that is inaccurate enough to be almost funny.)

Our next-door neighbor’s son, Arthur Duke, was Jewish, but he didn’t look it. And Duke—could there be a more English name? He also was not obviously brainy. We played cricket and football in his back garden, my cricket slightly better than his, his football considerably better than mine. He invited to me to his bar mitzvah, which remains one of only two times I have seen the inside of a synagogue. He didn’t talk about the preparations much, but apparently had to learn a big speech by heart. I thanked providence that I had not had to endure the same duty.

And that, for the next two or three years, was the extent of my involvement with Jewishness—until we get to my next school. At the age of thirteen, I moved on to Westminster School. Founded, officially, by Elizabeth I, but with roots in the tenth century, this was the kind of school that The Hall bent the knee to. It sits just across the road from the Houses of Parliament, right next to Westminster Abbey. Westminster was mostly a boarding school, and had its own fearsome rituals, like the Greaze, in which a boy from each class competed for a piece of a huge pancake tossed by the cook over a high bar in the main hall; it was a violent, lawless scrimmage, watched by the whole school (about 500 of us), until the boy who emerged with the largest morsel at the end of the mayhem would be deemed to have won and would receive a piece of Maundy Money, or a golden guinea, from the dean.

The archway framing the steps leading to this hall was carved with names of former pupils, dating back, if I recall correctly, to the eighteenth century, a legitimized graffiti whose message was “you can get away with this kind of thing here, if you’re the Right Sort.” The school’s position regarding the Establishment went even deeper than history and proximity. It involved living, and potentially endless, ritual. The Queen’s Scholars, an elite group, were allowed to watch parliamentary proceedings; when a new monarch is crowned, they take part in the ceremony, and shout “Vivat!” You get the picture.

As, at the age of thirteen, I didn’t want to board, I was sent to a house called Ashburnham, which, I soon learned, was where they put the misfits. It was slightly set apart from the school, and the boys placed there were those not destined to become, as all the others were supposed to be, future diplomats and senior civil servants; they were often the children of foreigners, or at least people with foreign names, or ambitious members from the lower slopes of the middle class, wealthy enough to pay the fees, but not, you know, of the Right Sort. My best friend was the son of a brick merchant.

One of the subjects I elected to study in the Sixth Form was German, and so, what with one thing and another, the Jewish business came up again. On the cusp of my sixteenth birthday, our class was packed off for six weeks to a school in Munich, to stay with German families while their offspring came and stayed with ours. At that time, the consciousness of Nazi atrocities was well embedded, and we had moved on to jokes about Not Mentioning the War, in gleeful reference to John Cleese’s performance in an episode of the sitcom Fawlty Towers. We were somewhat wrong-footed when our first lesson in a German school, notionally a math lesson, began with the directive: “Today, we will talk about our War Guilt.”

Advertisement

The German boys assigned to guide us were themselves keenly aware of historical ironies. I was told, deadpan, by one of them, that the father of the family I was staying with had served as a tank commander in an SS regiment on the Eastern Front, a tidbit of information that I suspect was deliberately chosen to give me the heebie-jeebies. (I file this under the heading “Relatively Sophisticated Schoolboy Humor,” as opposed to “Malice,” on the grounds that the German pupils I met were, without exception, generous, decent, and funny.) And as it turned out, the Meeses were kindness itself. One evening, Frau Meese announced that we were having ham for dinner and looked mortified on my behalf. It took me a few seconds to work out what she was driving at, but I assured her that was fine by me. The rest of the time, apart from lessons, was spent learning how to drink liter-sized Steins of Munich beer, including at the Hofbräuhaus, just round the corner from the Bürgerbräukeller where, we were told, Hitler had staged his putsch in 1923.

It was around this time, back at school, that The Conversation happened. During one of our dangerously unsupervised art classes, run with terrified laxity by a nervous young woman, I noticed I had been quietly surrounded by a group of three boys of my age, all of them Queen’s Scholars. I can remember their names.

“Lezard?” asked one. “Are you Jewish?”

“No,” I said, “I’m not.”

“Well then, you won’t mind saying ‘Jews are the scum of the earth, and up with Adolf Hitler.’”

“I’d rather not.”

“Go on, just say it. They’re only words.”

At this point, I contemplated saying those words. I ran them through my head. I wanted the situation resolved, and entertained the possibility that compliance would do so. But I knew it wouldn’t, and that I would have been shamed, in their eyes and mine. Then again, these boys, the elite of the elite (I hope you can imagine the look on my face as I type those words), were those whose acceptance I wanted. Not craved, but wanted. They were cool, at the apex of the school’s hierarchy.

One of the boys, whom I will call A—, didn’t have much of a character; tall, with glasses, slightly more acne than was normal, he was the kind of person whom I can picture with ease as a senior functionary in government. The second one, whom I’ll call P—, surprised me by his taking part in this little show. He was beefy but jovial, with a good wit and, I thought, a capacity for friendliness. In fact, I had thought we were friends.

Standing apart was one whom I will call C—. C— was another matter. Stringy and aloof, with a mop of blond hair and a don’t-give-a-damn charisma, he acted as if he were cleverer than everyone else, and he generally pulled it off. I cannot confidently state the degree of C—’s complicity with his friends (for the three of them were, generally, inseparable). I have a fancy that he may even have rolled his eyes, as if in rebuke or exasperation. What I mainly remember thinking was something along the lines of “Well, if this is the best this system can produce, then I want no more part of it.” However—and here is the terrible thing—I cannot be entirely sure that I refused to say those disgusting words. Let me say, for the sake of my own peace of mind, that I did not do so. But I want to raise a doubt, because it is important.

Once one has escaped from a place, one revisits it only in dreams, or in the involuntary burps of memory, or by chance. On one occasion, I saw A— walking down a London street, looking, to my satisfaction, shambolic and distressed; and once, in the visitors’ register of a Moroccan hostel, I saw C—’s name. But I thought no more about him until, in 2001, he helped to found the Stop the War Coalition.

The Stop the War Coalition was founded in response to America’s reaction to September 11, when it became immediately obvious that George W. Bush’s administration was going to use the attack as a justification for invading Iraq; the march it organized in February 2003 against the invasion remains the largest protest in the UK’s history. A huge cross-section of the country applauded the coalition’s aims, including me.

Since then, though, the clear stream of left-wing conscience has been muddied. The Socialist Workers’ Party, an offshoot of the left that C— once belonged to, has been tainted by accusations ranging from sexual exploitation of its female members to anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, the Labour Party is thrashing about trying to extricate itself from a similar charge, and its leader, Jeremy Corbyn, has made a very poor job of convincing the majority of British Jews that he is not an anti-Semite himself.

As for the Stop the War Coalition, it has come under fire for printing on its website (before removing them) denunciations of Israel that shade into straightforward, old-fashioned Jew-hatred. At the same time, there have been almost numberless recent incidents throughout Britain in which Jews have been insulted specifically for their Jewishness. It is as if something that every respectable, decent person had considered dead and buried had only been sleeping. There are increasing numbers of attacks, verbal and physical, on Jews in this country, as is the case around the world. The Jewish community center in Hampstead, JW3 (a pun on Hampstead’s postcode, NW3), has security guards. Even before the mass shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue by an avowed anti-Semite named Robert Bowers, Jewish communities in the US, the UK, and elsewhere in Europe were taking measures against a wave of anti-Jewish hate speech, vandalism, and attacks.

My friend the novelist Linda Grant, herself a Jew, likes to claim that I am, in fact, Jewish. She points, whimsically, to several factors: my bookish, cerebral nature, my dislike of exercise, my particular sense of humor, my poor dancing, my upbringing in St. John’s Wood and East Finchley, two of the most Jewish areas of London. If I’m honest, I find myself flattered that she considers me one of her own—though it is also teasing because she knows it makes me uncomfortable, the feeling that I am claiming something that’s not mine. And not too long ago, I went out with a woman who developed the same conceit, and whenever she talked about Jews, or of one of her many Jewish friends, she would use the phrase “your people.” This was a lot less funny, because she wasn’t Jewish herself.

And so I find myself in the strange position of being someone who is becoming very personally alarmed at anti-Semitism without actually being Jewish. Should the worst come to the worst, and I’m not fingered—though I can’t be sure I wouldn’t be—what would I do? Would I stand up and wear a metaphorical yellow star out of solidarity? I might not have a choice. The sad or alarming fact is that many people carry their own Nuremberg Laws in their heads, and these are perhaps not as pseudo-scientifically nuanced as the original ones to make a distinction between Mischlinge zweiten Grades and Jude.

Yet I can claim no close, direct kinship with Jewish culture, whatever anyone thinks. Only sympathy and appreciation. An ancestor of mine, Captain Arthur Gower Lezard, has a grave in Bienvillers Military Cemetery in northern France (he was killed in action in 1916), and his headstone has a prominent Star of David on it. I now post a photo of it on social media every year on Remembrance Day. Doing so makes it harder for me to say, “I’m not Jewish,” which is perhaps one of the reasons I put it up there.

So what am I? I do not strongly identify as English, especially since the Brexit referendum; I now live in Scotland. But my accent is English, I went to those schools which, for many, represent a plush ideal of Englishness. I listen to BBC Radio 4, would be uninterested in a heavenly afterlife if it did not contain an English country pub, and cherish my membership in the Marylebone Cricket Club above pearls. But are these the shibboleths of the native, or the kind of thing an outsider is meant to do in order to consider himself accepted?

There was a sketch performed by the comedy troupe Beyond the Fringe many years ago, in which Jonathan Miller (still with us, thankfully) said that he wasn’t really a Jew, just “Jew-ish.” That got a laugh in the 1960s; a shocked laugh, perhaps, but that was what was aimed for. Whether it would get a laugh these days, I am not sure. Every single Jew I know, and I know plenty, observant or not, confesses nowadays to being suddenly very aware of their Jewishness, and alive to the potential reaction it can provoke from both the right and, more worryingly (given its professed antiracism), the left. I, too, have been the target of anti-Semitic abuse in the last two years. If someone like me, with only the haziest notion of what the Torah or the Talmud are, can be such a target, I wonder at how much hatred is out there, waiting to boil over again.