Today, photography’s ubiquity makes it hard to imagine the infancy of the form, when creating just one image was a painstakingly delicate process. In 1843, Anna Atkins, daughter of the prominent British scientist John George Children, began work on her book of photograms (the full edition of which would include over 400 prints) documenting specimens of British algae, what is now considered the first book to be fully illustrated with photography and the first use of photography for scientific documentation. Two exhibitions at the New York Public Library’s Schwarzman Building, “Blue Prints” and “Anna Atkins Refracted,” celebrate this astonishing historical achievement, as well as the legacy of Atkins’s work for contemporary artists.

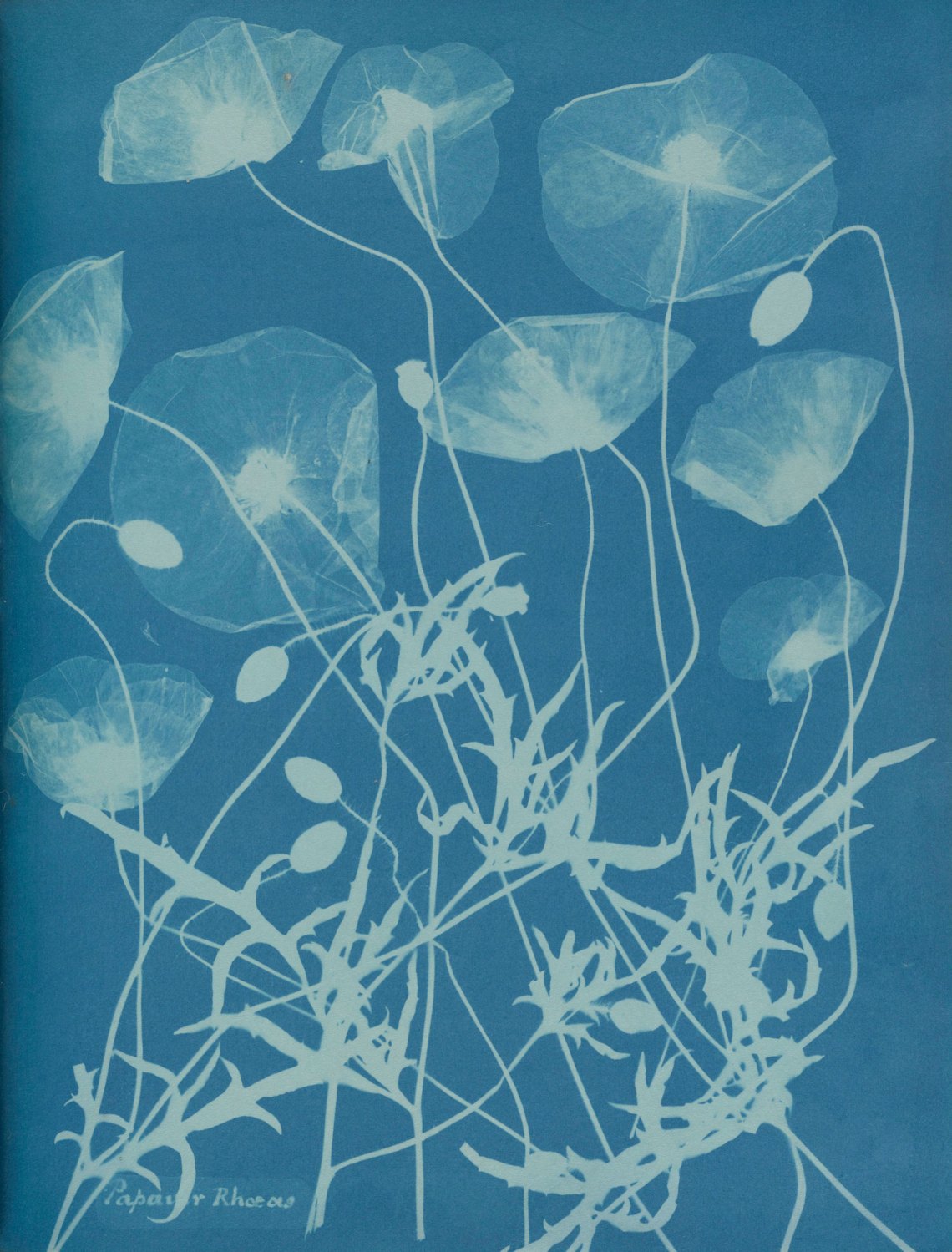

Exposed to her father’s scientific research and colleagues at a young age, Atkins developed a passion for nature, science, and drawing from life. As an adult, she practiced lithography, watercolor painting, and became enthusiastic about botany, a rare acceptable scientific pursuit for women, becoming a member of the Botanical Society of London shortly after its formation. Atkins’s project grew out of her interest in artistically and accurately documenting the natural world. She began printing around the same time Henry Talbot made public his own development of printed photography and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced his development of daguerreotype photographs. Photographic advancement was in the air, but not in the form we are now familiar with. Atkins’s own method was the cyanotype, today more commonly known as the “blueprint,” developed by her father’s close friend Sir John Herschel in 1842. The process is fairly simple compared with other photographic methods, as it involves only two chemicals—ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide—brushed onto paper, which is then left to dry in the dark, and used as the surface onto which a negative is printed to make a photograph. Alternatively, an object can be placed on the paper to make a photogram. When exposed to sunlight the chemicals bind as a water-insoluble dye, which, when oxidized, gives a cyanotype the deep blue tones it is named for.

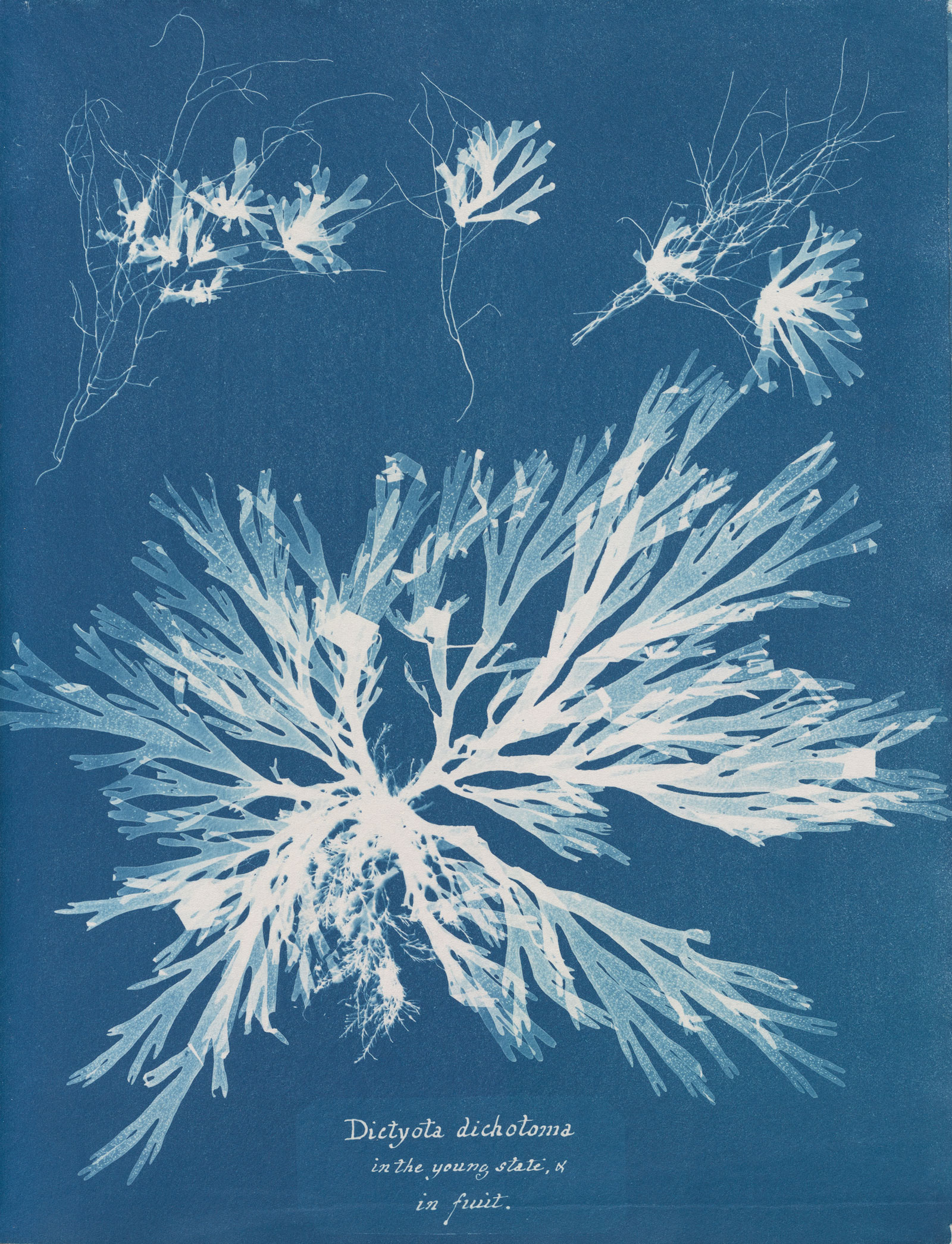

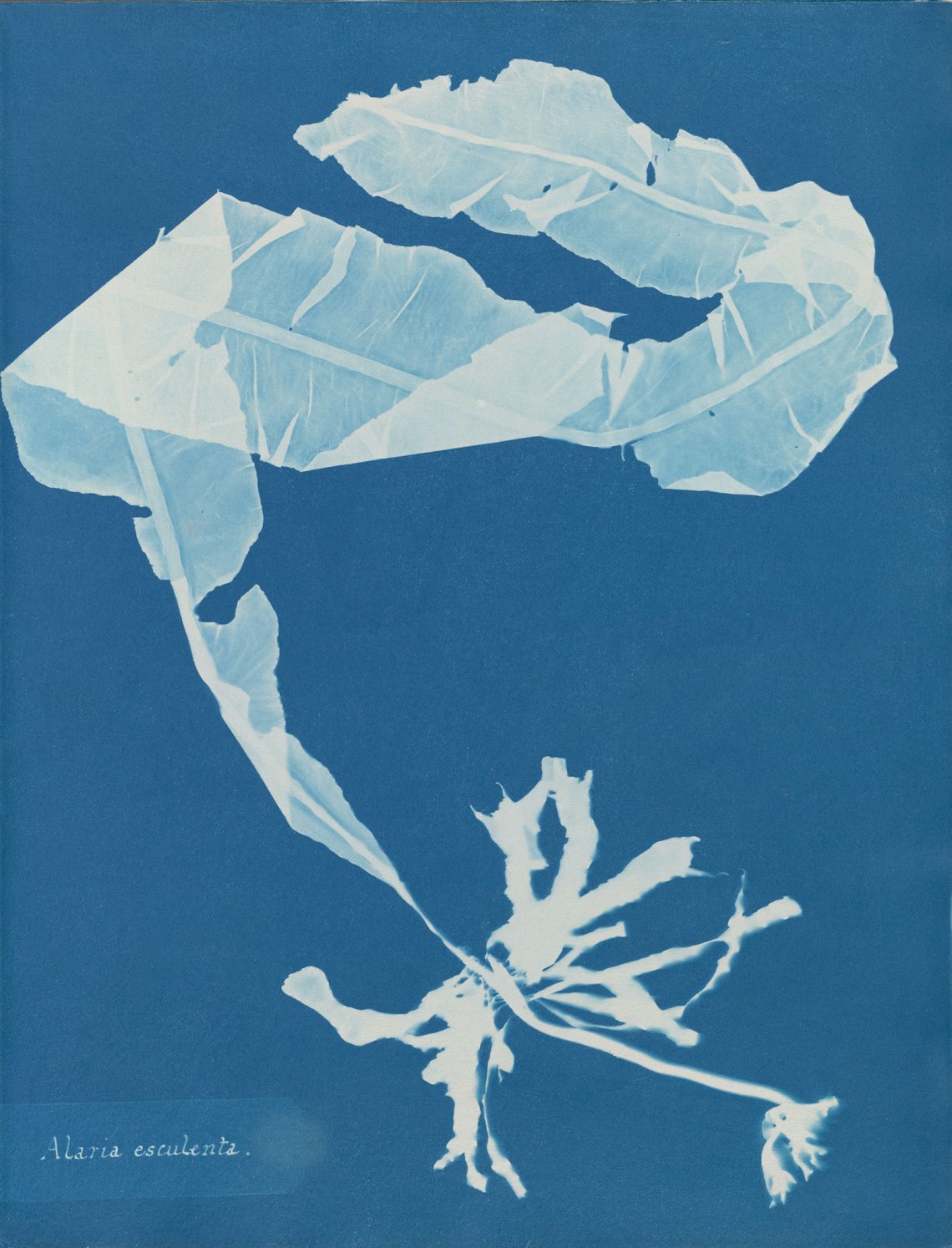

In a dimly lit gallery in the library, “Blue Prints” gathers letters, published writings, prints, and several volumes of British Algae spread open on stands in glass cases. The books are carefully displayed on mounts with the thick rough-edged blue pages stacked against each other. The walls are also lined with prints from several disassembled volumes of Atkins’s algae book and later album Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns. But the emphasis of the exhibition is on the publication of Photographs of British Algae (1843–1853 or 1854), which took ten years to complete, as well as her later collaborative experiments with cyanotypes made with her close friend Anne Dixon. The clarity and number of Atkins’s exposures demonstrate remarkable technical skill and attention to composition. Each page was printed by hand, with the dried algae delicately arranged close enough to the paper to produce a sharp print without damaging the specimen.

The algae, silhouetted against the blue paper, writhe and loom menacingly over the page, proudly attesting to their nickname “flowers of the sea.” Some specimens appear as wispy scraps about to be brushed away, like the thin clustered strands of Polysiphonia violacea or Banoia fusco-purpurea. Others, such as the thick leaves of Humanthalia lorea, look more like spring onions with shoots curling and flowing toward the top edge of the page. The tenebrous, intimate space of the library gallery serves only to enhance this mystical quality.

In addition to creating delicately hand-cut pages, Atkins hand wrote the names of each specimen below the image and on detailed “Table of Contents” pages, recording the names first on transparent paper that then served as a negative to be printed on multiple pages. This reinforces the intimacy of the book and also makes it “the first book in any field—in any country—to be printed using photography to replace typesetting and conventional means of illustration,” Larry J. Schaaf notes in the expanded edition of Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins, originally published in 1985 and republished to accompany the exhibition. “She capitalized on the flexibility of photographic printing by designing the titles in her own special script,” Schaaf writes. “The letters appear to have been formed from delicate strands of seaweed, and while actual specimens could have served for this, she may instead have applied her skill as a draftsman to the task; they may possibly even be a hybrid, with written letters embellished with strands of actual algae.”

Advertisement

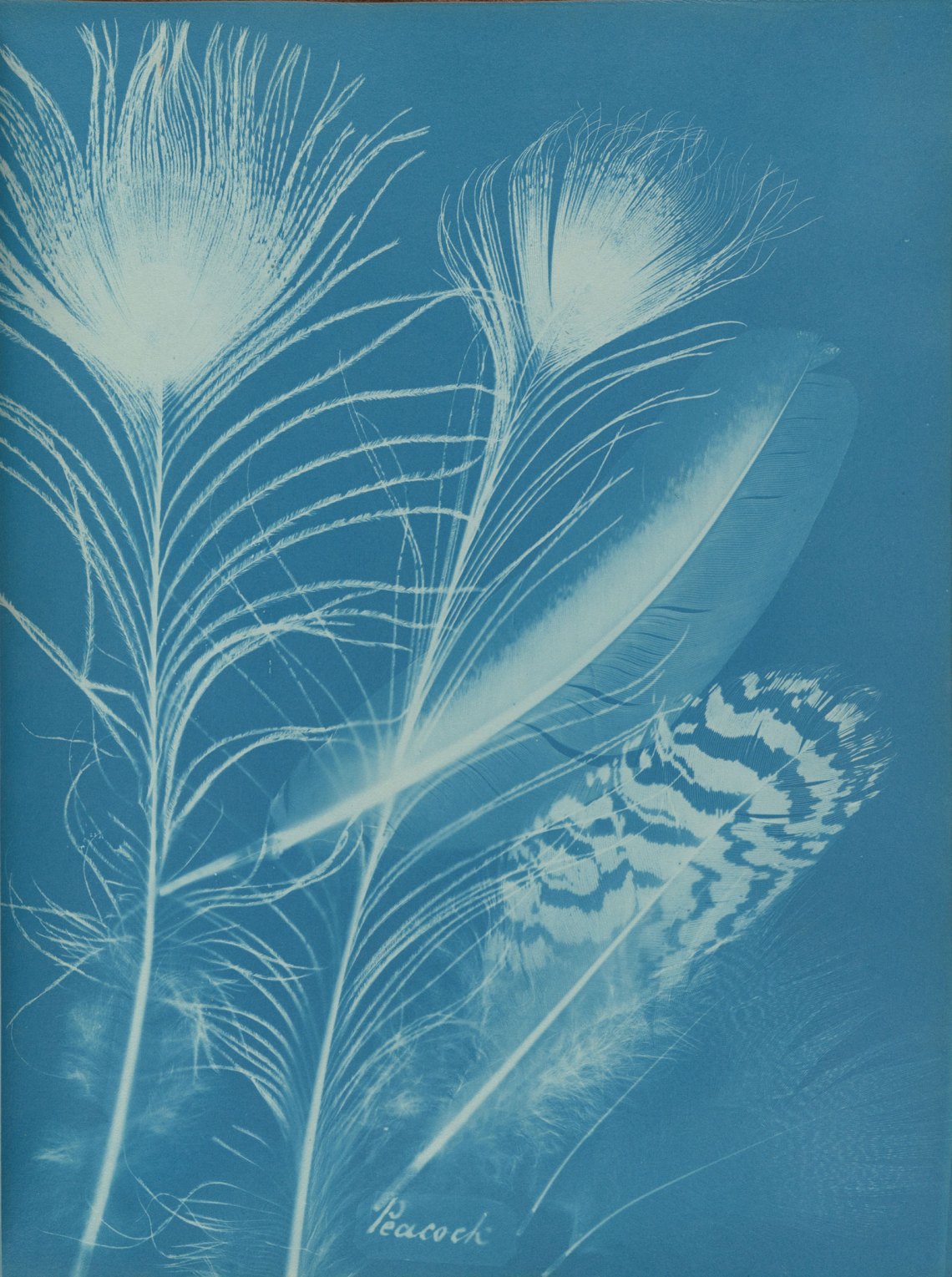

While British Algae is the focus of both the exhibition and Sun Gardens, Atkins’s most creative work came after its completion, when she turned her focus to working with Anne Dixon to make cyanotypes of ferns, produced as an album, and prints of lace, peacock feathers, and other decorative materials. These are more expressive than the scientific style of the algae portraits. In her later prints, oats and guinea fowl feathers fill the whole page, even running off the edges, in full and complex compositions.

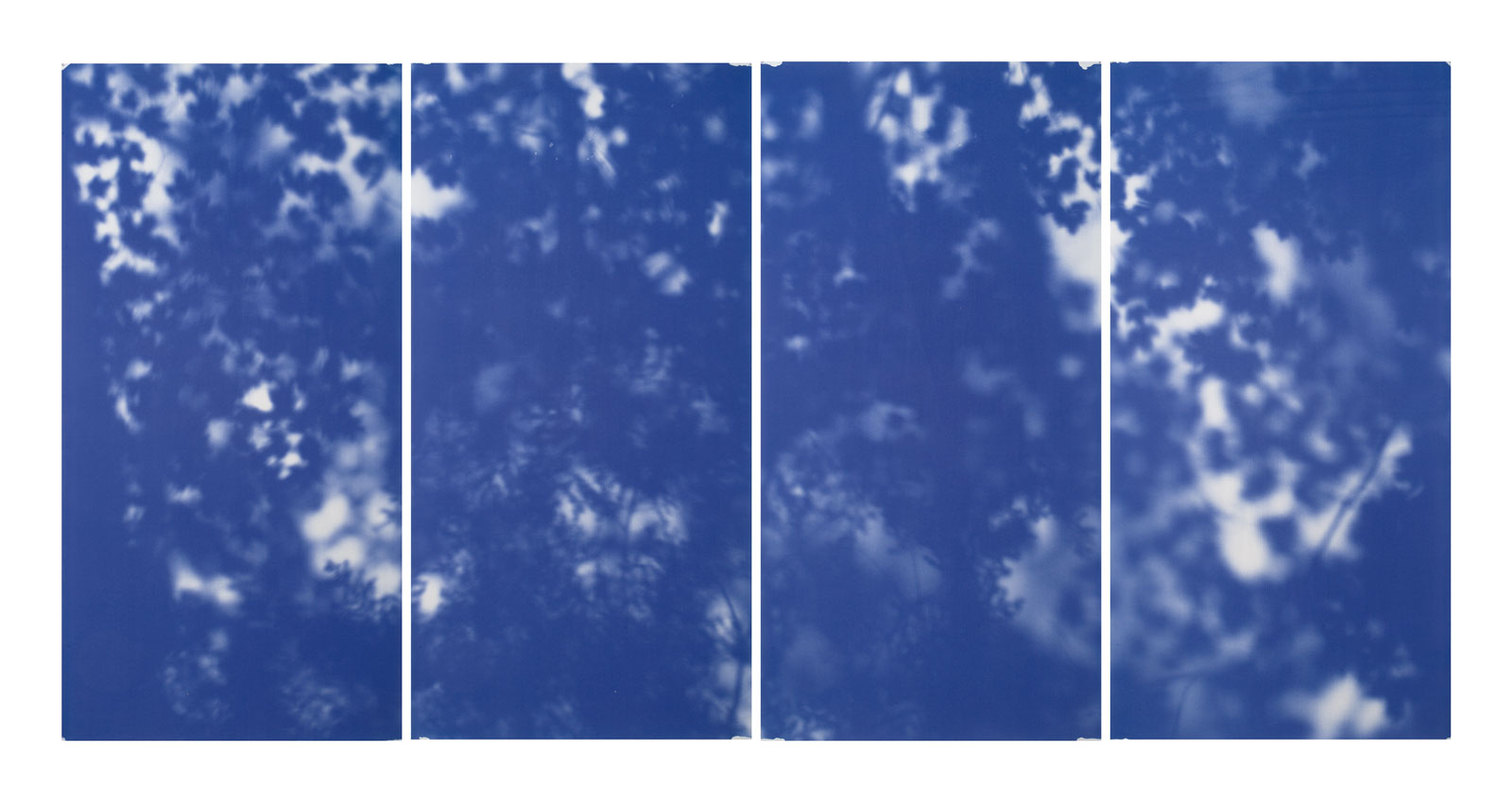

“Anna Atkins Refracted,” in the upstairs galleries of the same building, displays the work of more than a dozen contemporary artists influenced by Atkins. Some of these artists make work that directly reference Atkins’s methods: Meghann Riepenhoff’s series of cyanotypes with collaged algae, titled For Anna, evoke Atkins’s composition and subject matter with the addition of physical specimens placed directly onto the prints. Penelope Umbrico puts a more contemporary twist on the cyanotype, scanning the discarded screens from phones and computers and transforming the images using the “cyanotype” Adobe Photoshop filter to create images that share the same color palette as Atkins’s prints but document the angular geometric forms of our daily lives rather than the fluid organic sea materials that preoccupied Atkins.

Atkins’s achievements, like those of many Victorian women, were largely forgotten after death in 1871 and remained unknown for years. In 1895, The Photograph Naturalist mentioned her accomplishments with cyanotype printing; in 1990, she was granted an entry in the Missing Persons volume of The Dictionary of National Biography; and in 2015, she was honored by a Google Doodle to celebrate her 216th birthday. But the republication of Sun Gardens and the exhibition of her work marks a major effort to enhance her artistic legacy and acknowledge her contributions to scientific publishing and the history of the printed book.

At the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, “Blue Prints” is on view through February 17, and “Anna Atkins Refracted” is on view through January 6.