tell them we are descendants

of the finest navigators in the world

tell them our islands were dropped

from a basket

carried by a giant

tell them we are the hollow hulls

of canoes as fast as the wind

slicing through the pacific sea.

“Oceania” is not the historical, ethnographic show that Western museum-goers might expect. At the entrance a shimmering wave of blue material cascades from the ceiling. Titled Kiko Moana, this flowing wave uses ancient techniques of weaving, embroidery, layering, and cutting, but it’s a contemporary work in polyethylene and cotton, created by four Maori women from the Mata Aho Collective in New Zealand who have also compiled an online archive of stories about the supernatural spirits of the waters. Old and new technologies meet.

A constant oscillation between tradition and modernity runs through the exhibition, organized jointly with the Musée du Quai Branly—Jacques Chirac in Paris, which brings together objects from over twenty European museums as well as from New Zealand. The curators, Peter Brunt and Nicholas Thomas, insist that the arts of the Pacific should not be seen as idealized historical objects. Instead, their “real meaning” lies in the successive transactions from the eighteenth century to today—as gifts, objects of trade, and trophies of anthropologists and collectors. If this feels like a saga of plunder, “Oceania” makes it clear that exchange is a two-way process, and although the show marks the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s first voyage in 1768, its focus is not on Western expeditions but on the indigenous art of the diverse island cultures themselves.

For the islanders, the sea is their home: most dwellings are built on the water, except for those of communities in the uplands of the largest islands. But the ocean is also a road. Tahitian cosmological charts show the ancestors sailing star canoes across the heavens, the creator god Ta’aroa making his body into the first canoe and his descendants skimming over the waves to bring groups of islands up from the deep.

The actual canoes displayed, floating against deep blue walls, are objects of strange beauty. A shark-fisher’s canoe from Wuvulu, north of New Guinea, dug from the trunk of a breadfruit tree, has piercing finials echoing the shark’s fins. Nguzunguzu, a figurehead from a nineteenth-century war canoe from the Solomon Islands, stares out into the room, holding a pigeon, valued for its ability to fly straight to other islands over great distances. Weather charms, woven around stingray spines, conjure up the great navigators from the Marshall Islands, whose exquisite stick charts, delicate assemblages of wood and fiber and cowrie shells, were mnemonic devices to help them navigate the swells and currents.

The settlement of the Pacific Islands began around 30,000 years ago, but the origin of their varied yet connected cultures stems from the time of the Lapita peoples, who settled the archipelagos of Melanesia and Polynesia around 1350 BCE, finally reaching Hawai’i in the north, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, and New Zealand in the south between 800 and 1200 AD. One striking wooden figure from Aitutaki in the Cook Islands represents an ancestor who arrived in the canoe of the navigator Ru. Her head-to-foot tattoos tell of the founding canoes, but also of the birth channel and the ways of learning to be a woman—different forms of beginning.

Ancestral memory and ritual have always been central to island life and, at the opening of this exhibition, representatives from across Oceania joined a procession across London to perform ceremonies blessing the works on display. One room, titled “Making Places,” is filled with emblems rooted in place and community. Decorated beams carry carved birds and fish, while extraordinary gable sculptures cast shadows on the walls, including a slim, painted figure from Lake Sentani in West Papua mounted on a huge fish. In all places, at all seasons, the spirits appear, embodied in dynamic carvings, shields, armor, and ceremonial dance wands, clubs and costumes and dramatic masks, like the huge-eyed Kavat mask of the Baining people from New Britain, Papua New Guinea.

Advertisement

The sense of mana, a spiritual power or force connected with authority, is strong in these pieces, and the gods take many forms. Moai Havas from Rapa Nui, is a black, pock-marked hulk of basalt: the name can mean “dirty,” “rejected,” or “lost,” and it’s hard not to feel that this mournful figure, collected on Easter Island in 1868, should return to join its fellows. Other startling images range from the tubular ’Oro, from the Society Islands, woven in coconut fiber, or the fierce, lavishly carved Ki’i from Hawai’i to the austere, startlingly modernist-looking Tino aitu from the Caroline Islands. One can see how the sight of these figures, then labeled loosely, along with Indigenous African works, as “primitive art,” exercised such a powerful influence on European artists like Picasso, Modigliani, Brancusi, and Henry Moore. Their simplicity and boldness, mask-like faces and robust forms—entirely at odds with Western convention—set these European artists suddenly free, as if launched into an entirely different mode of expression and power.

That potent artistic exchange, leaping between cultures and reworking ancient forms in a new present, is in tune with the dynamic of art within Oceania itself. The exhibition illustrates the long tradition in which families, friends, communities, and islands have exchanged gifts: necklaces in whale ivory, shells, and seeds, patterned and decorated barkcloth, and patchwork quilts. These exchanges brought prestige, eased negotiations, and cemented relationships, and it was in this spirit that islanders lavished gifts on the strangers who arrived in the eighteenth century, including the amazing, baffled-looking images of gods, created of feathers, given to Cook in Hawai’i on his final voyage in 1779. Sadly, such gifts failed to conquer tensions: Cook would die soon afterward in a skirmish at Kealakekua Bay. During his three voyages of “discovery” from 1768 to 1780, forty-five islanders had been killed in violent encounters, while many more died of the new, imported diseases, which continued to taint later gifts of friendship.

In 1824, the Hawai’ian King Kamehameha II brought the blazing ʻAhu ʻula feather cloak to England as a gift to King George IV, hoping to strengthen diplomatic ties, but before they even met, Kamehameha and his queen, Kamāmalu, contracted measles and died. Disease is a theme of Lisa Reihana’s hour-long video panorama, In Pursuit of Venus [Infected] (2015–2017) . Stretching along an entire wall, the installation reworks Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, twenty wallpaper panels of Cook’s voyages designed by the French painter Jean-Gabriel Charvet around 1804–1806. Using haunting sound, the video sets animation and scenes acted out by living islanders against the vivid wallpaper background, overturning any notion of benign encounters that still linger from the Romantic period of the wallpaper.

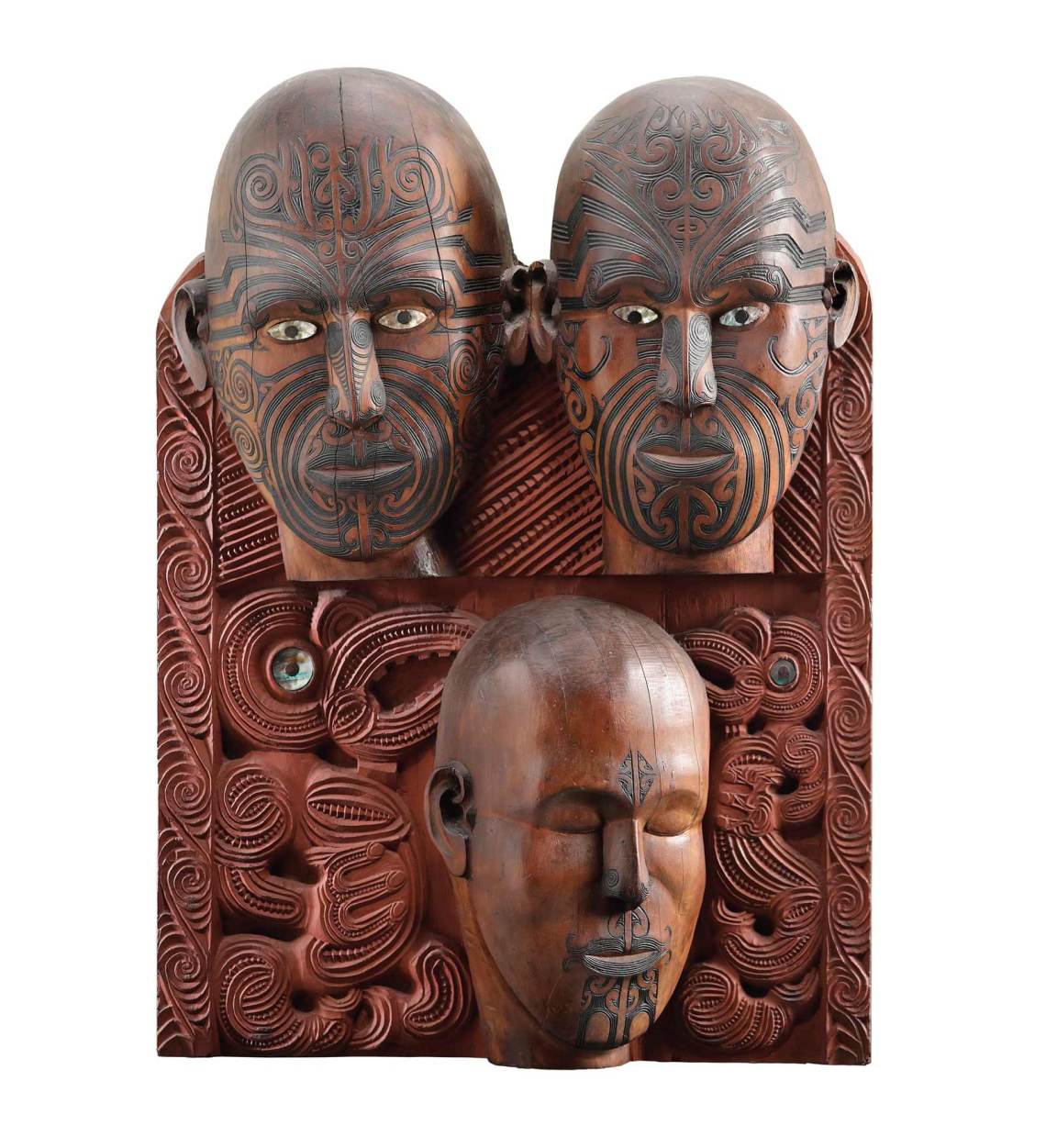

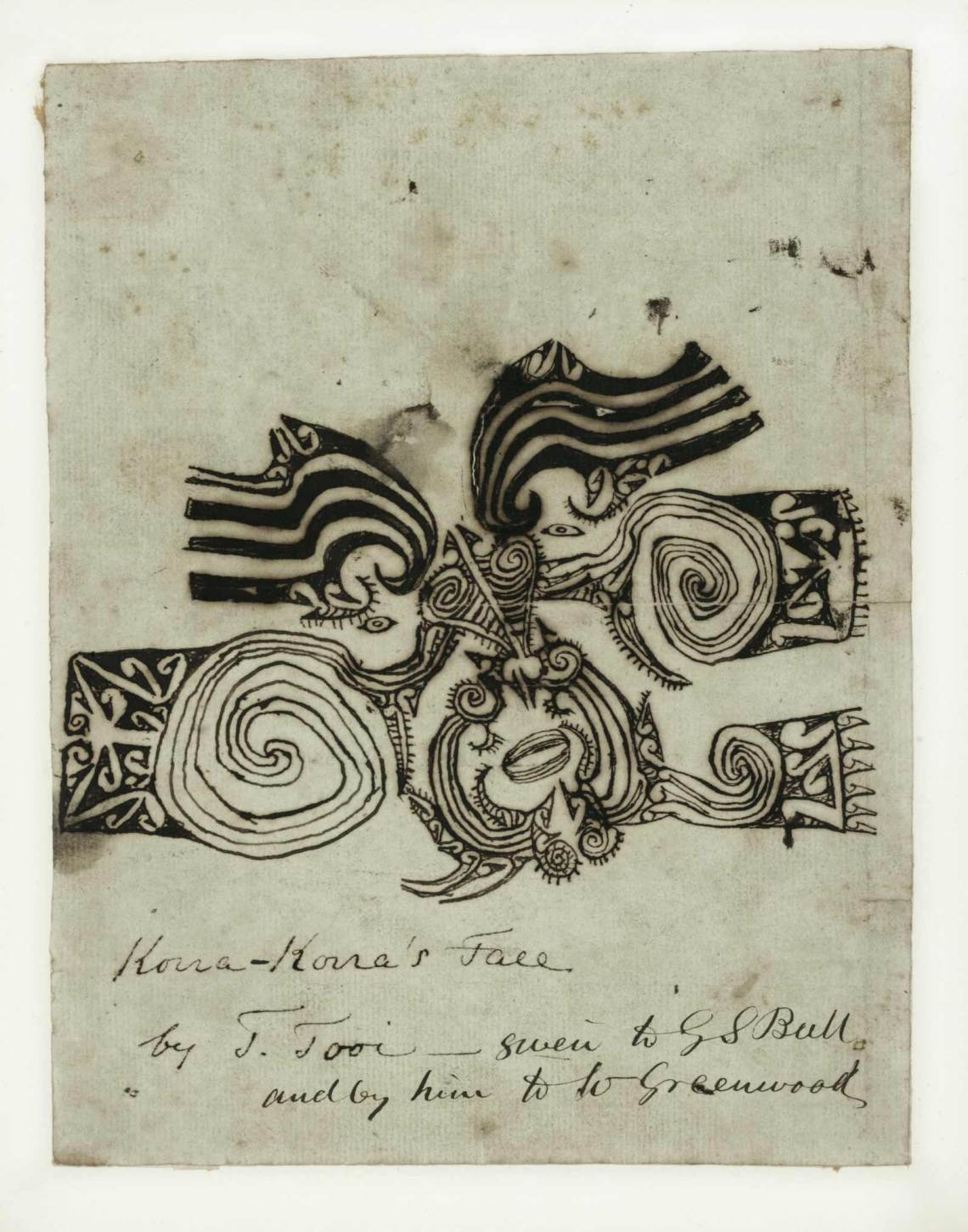

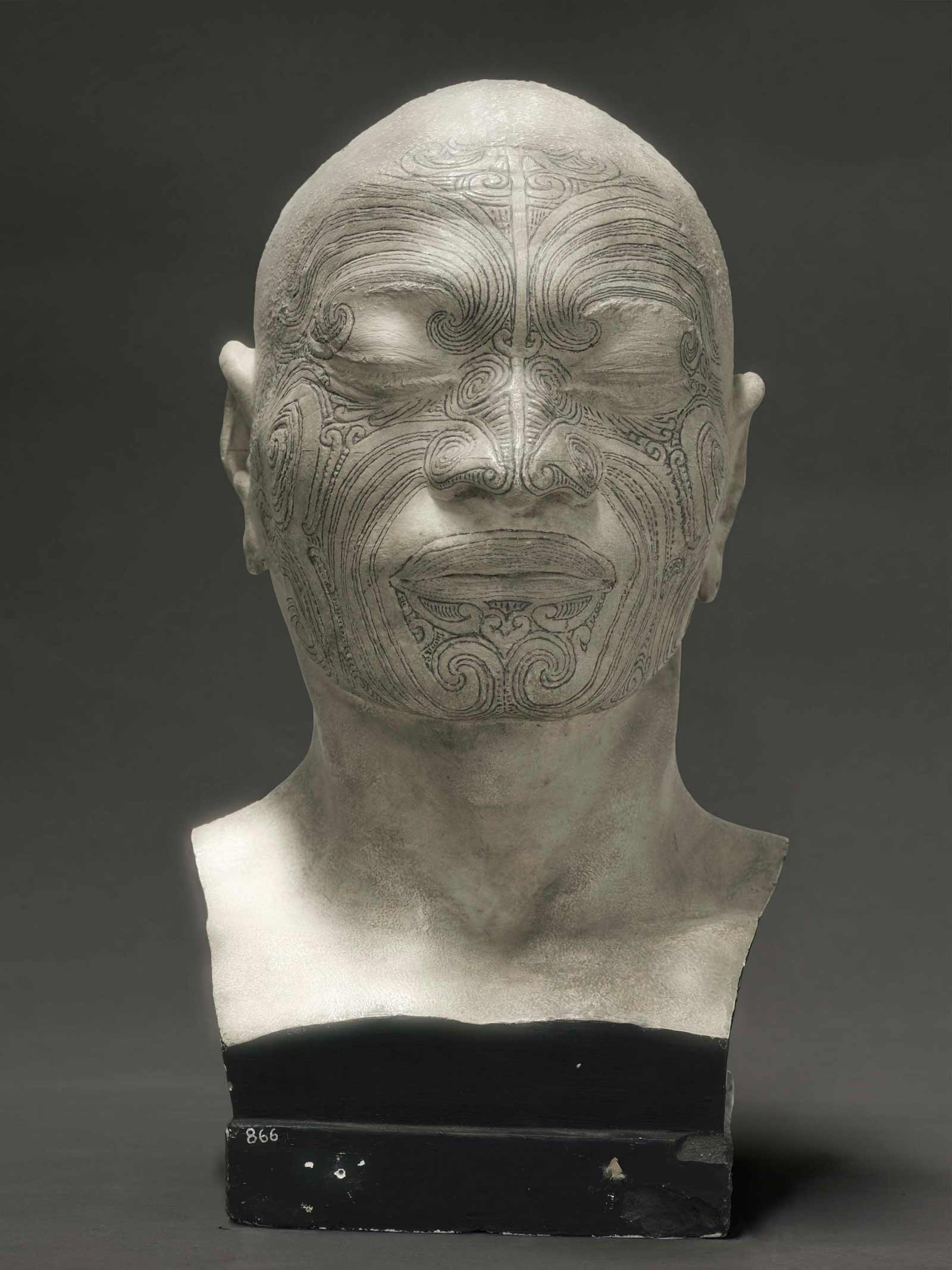

The years of colonization, entangling Oceania with the politics, commerce, and beliefs of the West, also filtered into its art: in a late-nineteenth-century Ngatu barkcloth from Tonga, the British flag joins stylized birds and traditional markings. Across the room, a Maori Madonna and child from the same period has glinting shell eyes and deeply incised tattoos. Art can cross boundaries of all kinds. Island rituals of mourning commemorated the dead while protecting the living from the lingering shades of the departed. To achieve this, the Pacific islanders created malangan, carved and painted forms that were used in ceremonies, performed sometimes years after a death, to release a soul. A fish malangan from New Ireland shown here, with glowing patterns of ochre and black, has narrow, hooded eyes and backward-curving tusks. A smaller fish swims alongside, and a tiny human figure sits in front, perched on the fish’s long tongue, ready to be launched into the afterlife. Conversely, the recovery of past lives is movingly demonstrated in Fiona Pardington’s The Pressure of Sunlight Falling (2010), a set of huge photographs of mid-nineteenth-century life-masks transformed by a subtle use of light so that one feels surrounded by living forms, emerging from darkness.

The far-flung archipelagos face new threats, as climate change brings rising sea-waters to encroach on their shores. The final room of this stunning exhibition returns us to the twenty-first century with John Pule’s vast painting, Kehe tau hauaga foou (To all new arrivals) (2007), where clouds and vines shower down over drawings of war and gods share in the continuing conflict. “Oceania” is a powerful demonstration of art’s capacity to fight the tide of loss, honoring tradition, reclaiming places, histories, and identities, and opening the way to the future. By celebrating the unnamed artists of the past, and those who continue to make work of strength and beauty, the show carries the freight of the sea-tossed Pacific story.

Advertisement

“Oceania” is at the Royal Academy of Arts in London through December 10.