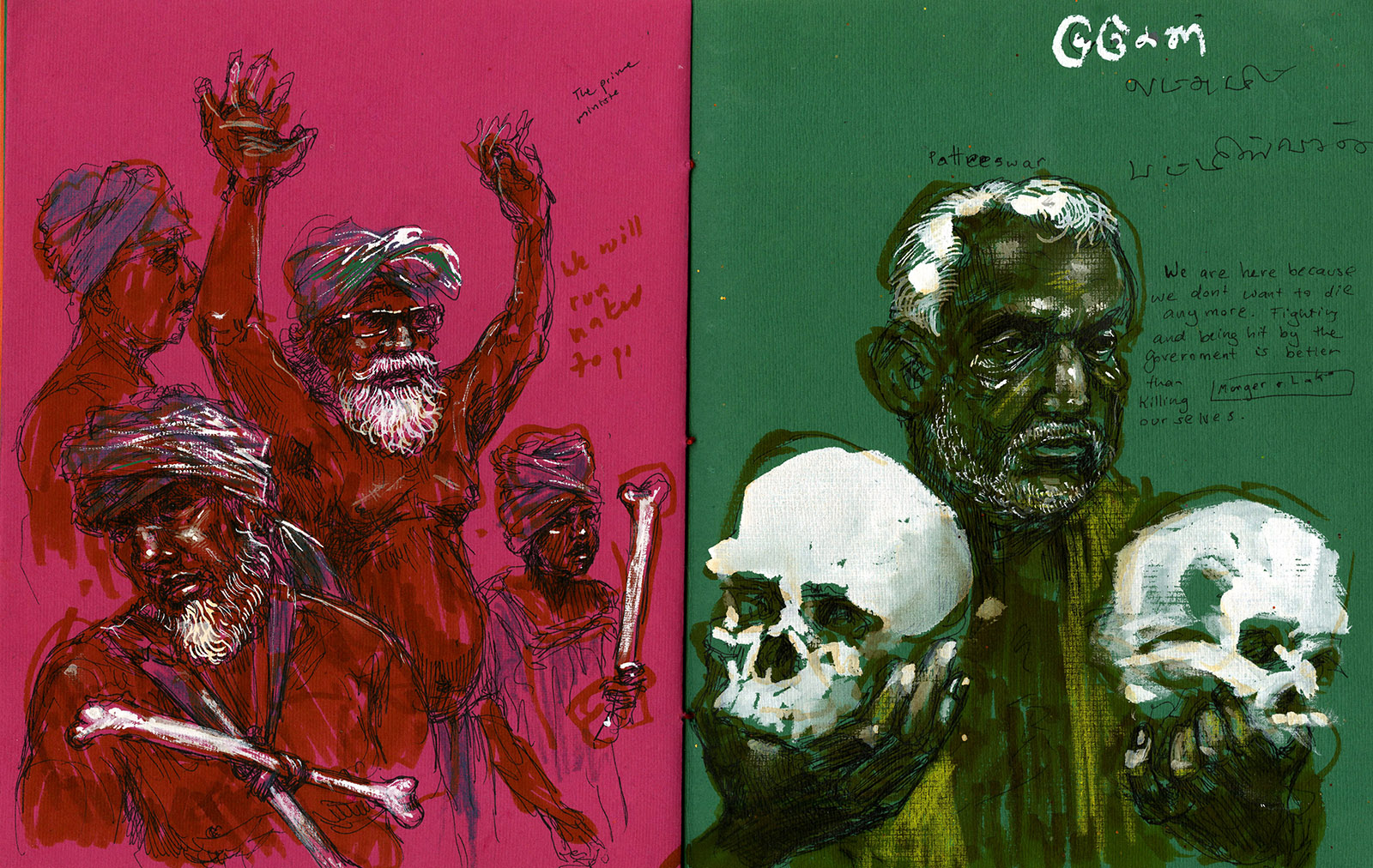

Potteeswaran, a rice farmer, said he was holding the skulls of Murugesan and Laxmi, a couple from Trichy in Tamil Nadu, who had killed themselves over a bank loan they couldn’t repay. “When the bank seized their land, they saw no other solution,” Potteeswaran said.

In April 2017, more than 150 farmers from Tamil Nadu sat for almost a month at Delhi’s protest hub of Jantar Mantar. They sat buck-naked, holding the bones of neighbors who had committed suicide, and bearing dead rats and grass in their teeth.

“In 2016, Tamil Nadu saw its worst rainfall in 140 years,” said Aiyyakannu, who led the farmers’ protest. “We wanted to symbolically shame our leaders into action.” They were back this time with farmers from five delta districts devastated by the Gaja cyclone.

New Delhi, India—Tens of thousands of farmers marched through the city in the last week of November. They came on trains and buses from all over India, and spent a cold night in a convention ground named for the dramatized Ramayana epic it annually hosts. The next day, their stomachs half-full on roti and tea that Delhi’s Sikh temples and student unions donated, they walked to Parliament Street. In a city choked with unbreathable air, they spoke in eight languages of failed crops, erratic rains, and their precarious lives.

Last week, a similar conversation was had in climate talks in the heart of Polish coal country. There, away from their electorate, world leaders uttered their worst fears out loud. Is our planet lost? How do we fight climate change? Diplomats negotiated global agreements for emission reduction, while US President Donald Trump tweeted triumphantly about how “ridiculous and extremely expensive” the Paris agreement was. Many politicians in rich countries are still focused on the least they can do, and are eager to use the Yellow Vest protests against French President Emmanuel Macron to make the argument once again that people are not ready for climate action.

But the farmers who marched into Delhi are. Agriculture in India relies heavily on rain and temperature in the growing season; farmers here are highly sensitive to climate. They have already felt the beginning of the apocalypse in the form of dried-up wells, declining yields, and mass migrations of people. Costs are mounting, while real farm income per cultivator has grown less than half a percent annually. An Indian farmer today earns under 20,000 rupees (about $280) a year on average, a quarter of India’s per capita annual income. According to official statistics available up to 2016, more than 320,000 farmers and farm workers have committed suicide since 1995.

Average rainfall has decreased in India and extreme events have become more frequent. Floods and cyclones devastate crops, but the seasons are also getting drier and drier. The monsoon comes later, and departs sooner. Studies show that the extent, duration, and intensity of monsoon droughts in India have grown since the mid-1950s. This is connected to reduced rainfall, which in turn is due to the narrowing temperature difference between the Indian Ocean and the Indian landmass. More farmers than ever are killing themselves over damaged crops.

More than two thirds of Indian farmland is irrigated by groundwater, which is fast running out. Taking a water break outside the Mahatma Gandhi memorial on the way to Parliament, Mallikarjun S. Doddamani said that every farmer in his village had dug at least two borewells in the past decade. Most are dry. He was from a southern district seeing its third year of drought. “The land is now like a beggar’s shirt—full of holes,” he said. After investing in four borewells in his six acres, Doddamani is now left with a 400,000 rupee ($5,500) loan he can’t repay.

Food insecurity, indebtedness, water scarcity, and depressed incomes underscored nearly every farmer’s story. Ramsingh Bharadwaj had traveled for thirty-six hours on foot, by bus, and finally by train from coal-rich central India to demand land titles for his community of indigenous forest-dwellers who both forage and farm. “As coal mines expand, we have lost both the forest and our access to whatever is left,” he said. On his phone, he showed me a picture of his lentil harvest, coated in black coal dust.

Climate change affects the rural poor the most. Karu Manjhi, an elderly Dalit farm worker from Bihar, had prepared a question for Prime Minister Modi: “How do you like it that a farmer in your country cannot feed his own grandchildren even one meal a day?” Manjhi’s two grandsons and three granddaughters ate rice with watery lentils at the government school, because he couldn’t afford to grow nutritious food in his one-acre homestead farm, now divided between two sons (63 percent of farmland belongs to marginal farmers owning less than 2.5 acres). “We all grow only one variety of rice because that’s the one the government guarantees a price for. One flash flood, and it’s all rotten.”

Advertisement

Each region and community had a different horror they couldn’t shake. They had waged their local battles, but the most generous state responses were short-lived fixes. Loan waivers to the drought-affected, flood relief, and insurance schemes do offer some assistance, but they don’t rethink what is grown, what farmers earn, and how water is used.

So the farmers had brought their bodies—ravaged by work, unaccustomed to television cameras after years of neglect, and weary from walking miles—to the seat of power. In a rare moment, landowning upper castes allied with landless farm workers; even if their interests often clash, they knew their destinies are linked. The farmers demanded a three-week special session in Parliament to discuss the agricultural crisis. Apart from laws on farm credit and remunerative prices, they wanted a debate on the water crisis and sustainable practices, in particular.

“We are the weather wanes, watch us closely,” said Laxmiprasad Verma, a farm worker from Varanasi who marched with his youngest son, eleven-year-old Naineeta. As thousands chanted “Marenge nahin, ladenge!”—we will not die, we will fight!—the farmers redefined themselves as the protagonists, not the fatalities, of the climate change story.

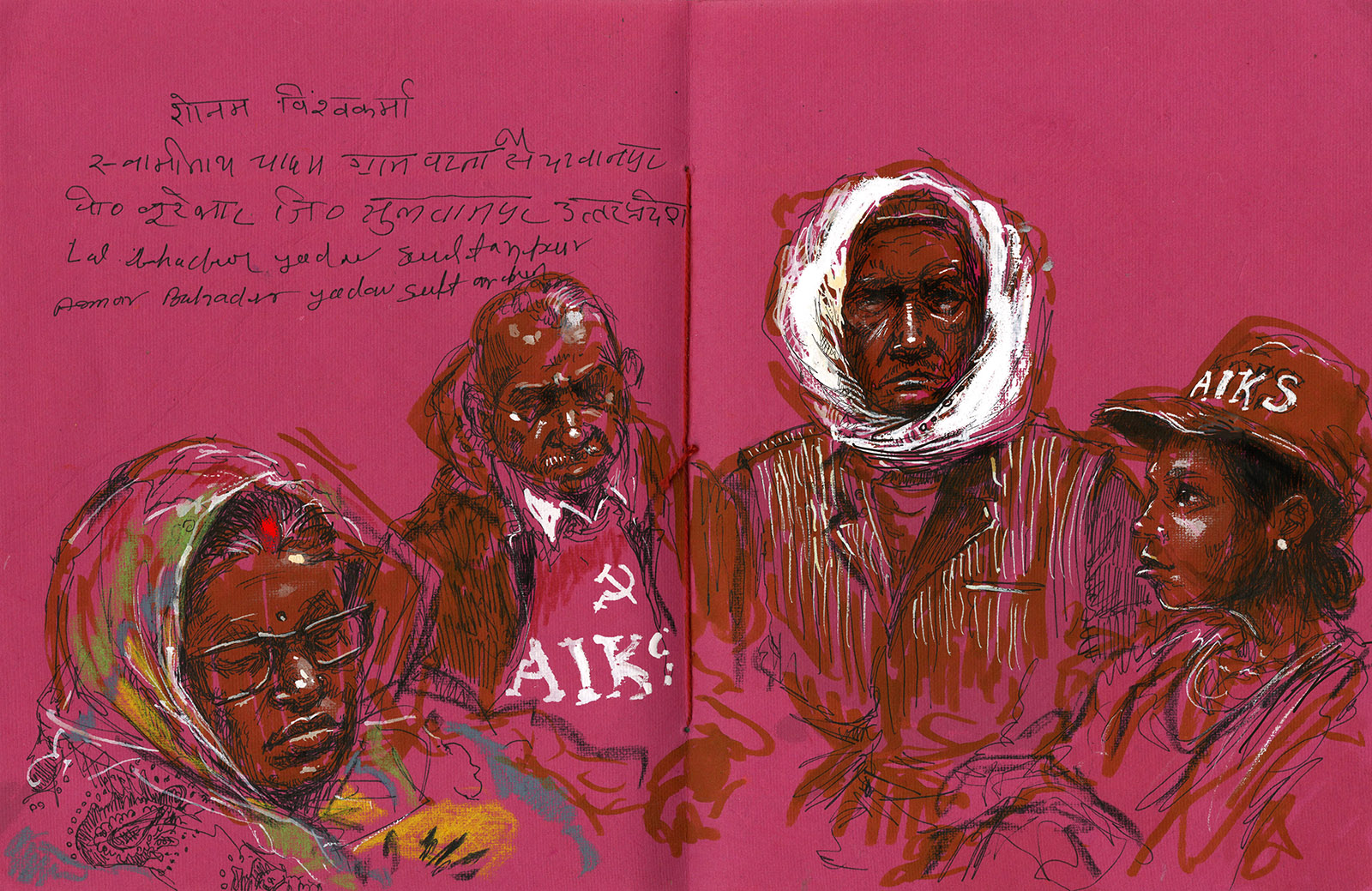

Around 200 farmers’ unions nationwide organized under the large umbrella of the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, but each district had been mobilizing on its own since August. The leading group was the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), a farmers’ union with Communist roots, but many of them were non-political, helping village associations bargain for better prices, decide what to sow, how to access markets, and push for subsidies and land reform.

Rajkumari, from Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, is a member of All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA), the women’s wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)—she called it aid-wah, pronouncing it like a Hindi word. This forty year-old has never heard of Marx; she panicked at the word “Maoist.” Politics, for her, is a form of self-actualization. “We women are taught to go hungry when food is scarce—that was the first thing I unlearnt,” she said. “Then I realized, I sow and harvest paddy, I care for cattle, I collect pots of water for the house. Why shouldn’t I get equal wages and land rights?”

“We just keep working harder and harder, spending more and more on wells or seeds or technology. But does all this work?” asked Mukhtayar Singh from Punjab. As the protesters awaited police permission to march, Singh walked around trying to speak to farmers from other states. Perhaps they had found other ways to adapt?

Most farmers, though, aren’t really changing their methods to adapt to a warming climate and water scarcity. Instead, they are boring into the ground 200 feet to find water—but, even at that depth, they often find none. Or they’re growing conventional crops that have guaranteed government prices, even though they use too much water and provide fewer nutrients. Rice and wheat are seriously affected by climate change but still dominate cultivation.

When nothing works, the farmers scrape together their last pennies to send their sons and daughters to school, to college, to the nearest cities. Fifty-seven-year-old Rulda Singh prays that his sons will never have to wield a plough. Nearly 8 million people had quit agriculture in the decade ending in 2011, the year of the last Indian census. Indebted farmers and out-of-work farm laborers are pouring tar, carrying bricks, or cleaning mall floors—they’re fading into the anonymity of the vast urban working class. India is producing more food than ever, but has about 24 percent of the world’s malnourished, and is far from tackling chronic hunger. “I eat wheat, maybe my kids will eat steel,” said Rulda Singh, laughing.

“What do they do in America? On TV, all their farmers are plump and rich, and their department stores seem so full,” Mukhtayar Singh said. “Maybe I should just go to America.”

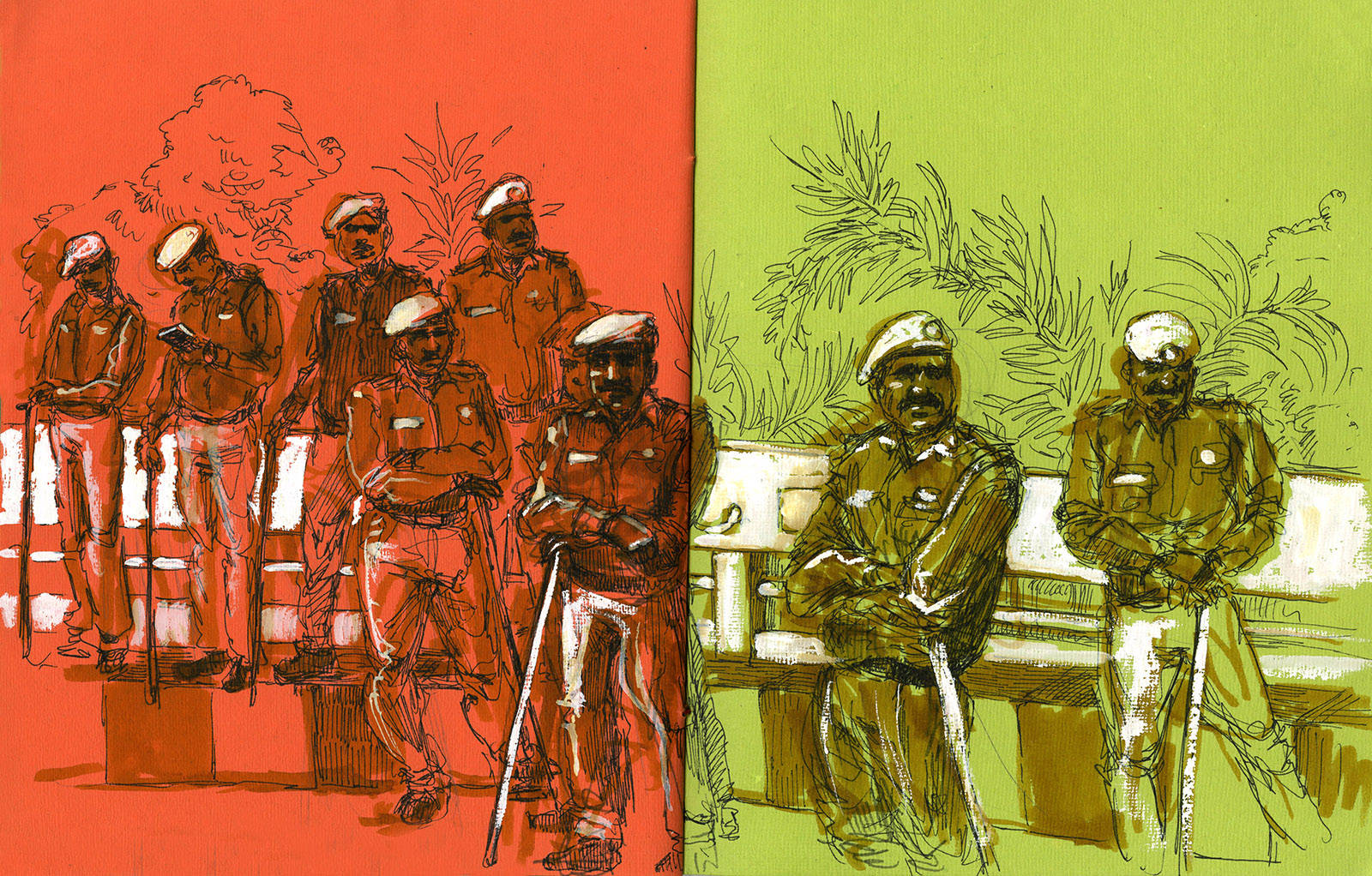

All public demonstrations in India need a police permit, and the Delhi police delayed granting one till the Sunday morning of the rally. They issued traffic advisories about routes to avoid during the two-day rally. About 3,700 police personnel and paramilitary forces lined the route. The sight of the yellow barricades and forbidding blue vans reminded forty-five-year-old Ramanamma from the southern state of Andhra Pradesh of the blast of water cannons on her back some years ago. At the time, her village had been demanding that the loans of tenant farmers like her be written off.

Farmers’ protests had almost doubled in two years—from 2,683 incidents in 2015 to 4,837 in 2016—and they continue to erupt. Tear gas and water cannons are regularly used against demonstrators. Last year, police firing with live ammunition killed six farmers at one protest. In March, about 35,000 farmers, most from indigenous tribes, walked more than 130 miles over seven days to Mumbai, demanding land entitlements. In north and west India, farmers dumped tractor-loads of onions and milk in town squares, showing their disgust for the prices they were forced to sell them at.

Advertisement

Women from southern Telangana walked with portraits of their fathers, brothers, or husbands who had drunk pesticide—the nearest available poison for a farmer drowning in debt. Banks tend to refuse loans to small farmers and farm workers, so they borrow from their friendly neighborhood moneylender at 300 percent interest. After her husband killed himself, Krishnamma received some modest compensation from the government. “The very next day, three debtors arrived at my doorstep—I gave them everything.”

The good news for Krishnamma is that she has held on to her three acres of land. The Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture, a nationwide informal network of 400 diverse farm organizations gave her training in sustainable farming. Today, instead of growing cotton and rice, she grows eggplant and chickpeas, which are more climate-resistant, or may even thrive in warmer weather.

Others from Karnataka practice “zero-cost farming,” in which they use hardier heritage seeds they can obtain for free. The Kerala government promotes share-cropping among marginal farmers, especially women, and incentivizes organic produce. At the Delhi rally, a handful of villagers from desertified Rajasthan were explaining watershed management to others from Bihar, which sees entire families of smallholders and farm laborers migrating. Even in the midst of the sloganeering and politicking, all that these protesters had on their minds was the future of their farms.