In 1976, James Baldwin released what is perhaps his most novel—and most often forgotten—book: Little Man, Little Man, a curious, hybrid-genre composition without precedent in his body of work. A few years earlier, his little nephew, Tejan, had asked Baldwin—Uncle Jimmy—to write a book about him on one of Baldwin’s visits to New York to see Tejan’s family at 137 West 71st Street. At the time, Baldwin was spending most of his days in a residence in the southern French village of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, so whenever he made the transatlantic trip to drop by his American family’s home, friends, kin, and strangers would simply appear at the door like moths to a lantern, seeking an audience with the great writer, and soon the apartment’s air would be thick with the sound of voices and music and sweet-pungent with the scent of whiskeys and wines.

Tejan and his sister, Aisha, liked to spy on the events; they had learned that their uncle was not simply popular in the neighborhood, but, as the siblings would boast to their friends and schoolmates, he was “an Author,” with a capital “A” that betokened Baldwin’s celebrity. One day, Tejan claims in the foreword to a lovely new edition of Little Man, Little Man—published last year at the urging of Baldwin scholar Nicholas Boggs, who co-edited the book—he caught his uncle by the arm. “Uncle Jimmy!” he yelled repeatedly. “When you gonna write a book about MeeeeEEE?”

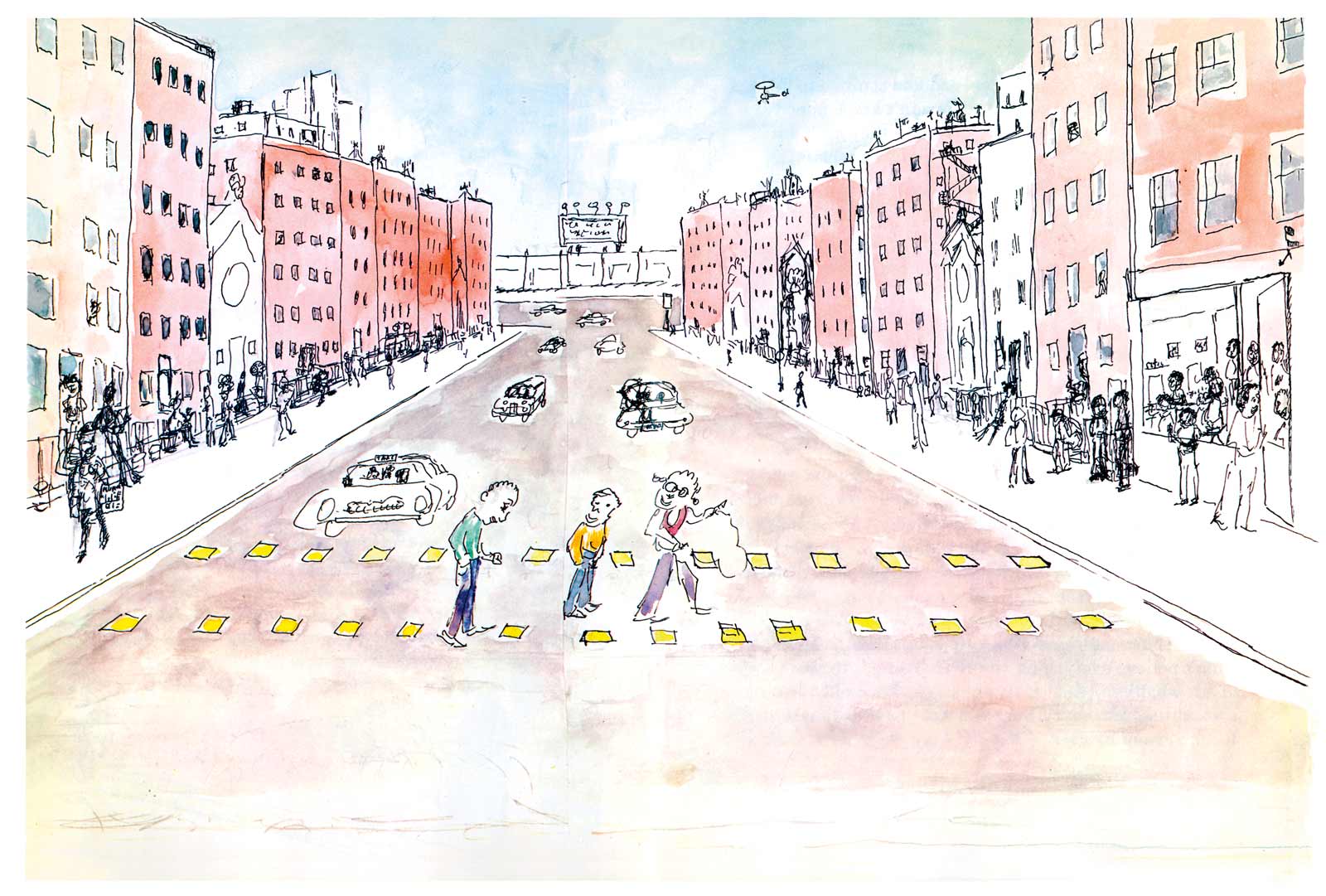

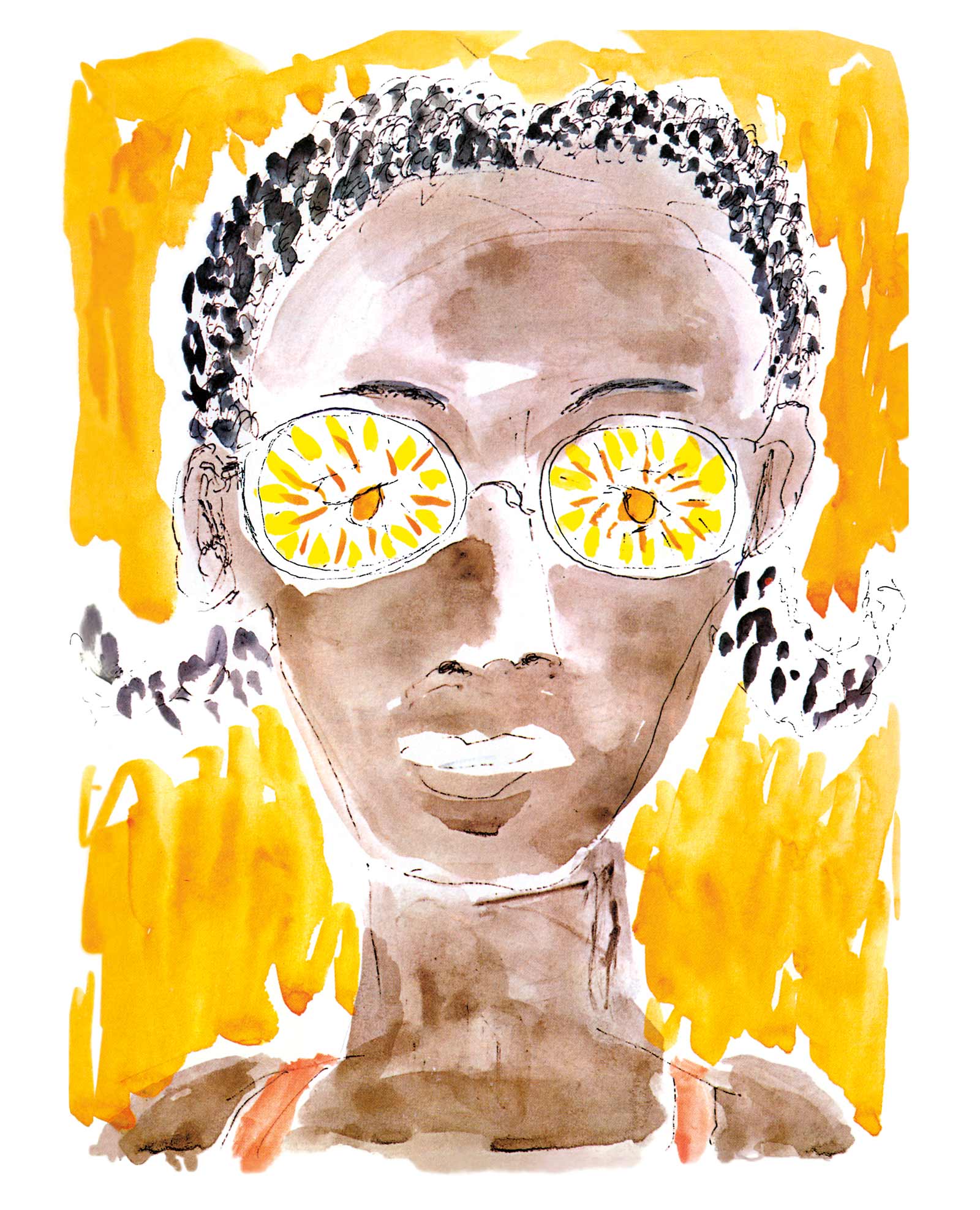

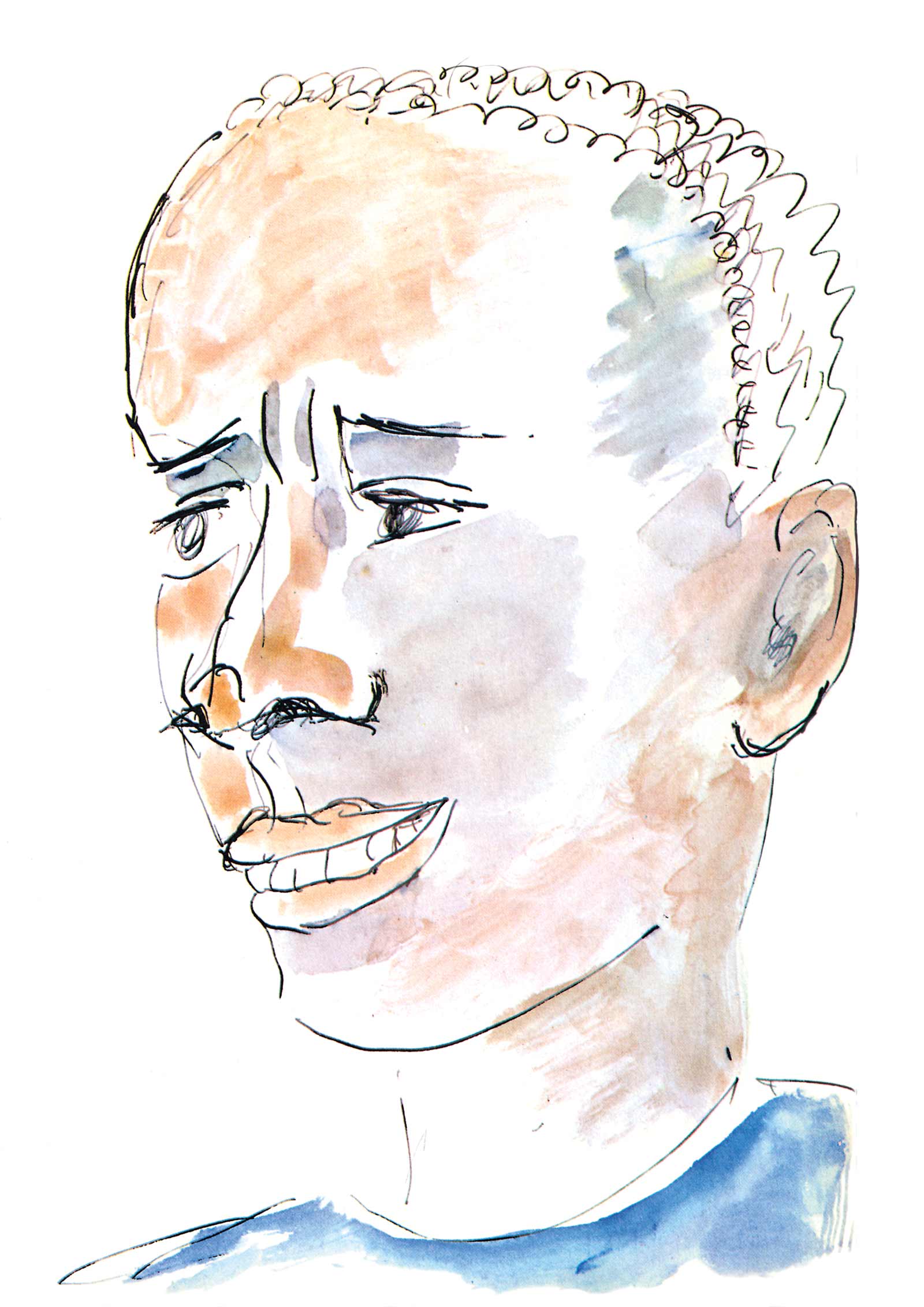

To everyone’s surprise, Baldwin finally did just that, crafting a remarkable book that follows a young boy named TJ—a stand-in for Tejan—through Harlem, along with a boy called WT and a bespectacled girl nicknamed Blinky. The book was illustrated with beautiful watercolors by the French artist Yoran Cazac, one of the men Baldwin was closest to in France, and was written in a childlike version of black American vernacular. Subtitled “A Story of Childhood,” the American edition described it as a “children’s book for adults and an adults’ book for children,” making explicit its extraordinary multiplicity: for kids and yet not for them, not unlike the way that Gabriel García Márquez’s best-known short stories, “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” and “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” are both subtitled “tales for children” in spite of their at-times-dense referentiality.

The ambiguity was well-earned. Little Man, Little Man defies conventional expectations for both children’s and adult’s literature, functioning, ultimately, as a liminal work that straddles the borders of both genres. In its lack of linear narrative, refusal to conform to standard English, and the sometimes wild, distorted art that accompanies it, Little Man, Little Man seems distinctly Modernist in sensibility for all that it still appears, at first glance, to be an ordinary children’s book. Clearer, however, is that it represents the artistic culmination of Baldwin and Cazac’s multilayered relationship, a collaboration that resulted, in Baldwin’s words, in a literary-artistic “celebration of the self-esteem of black children.” This statement doubtless resonated darkly for Baldwin, who had told a French journalist in 1974 that “I never had a childhood. I was born dead.” In a way, then, this story—both lighthearted and tinged with suggestions of violence—is also, perhaps, a missive from Baldwin to his younger self, describing a vision of childhood in the future that, while murky, is starrier than the one Baldwin had.

All this was lost on the book’s earliest reviewers, most notably the author and activist Julius Lester, who dismissed it in The New York Times as “a slight book” that “lacks intensity and focus.” Its dearth of a conventional plot made it, in Lester’s eyes, an inscrutable failure. Though he praised Baldwin’s language, he found Little Man, Little Man bland—“not… especially exciting or disappointing.” Had it not been written by Baldwin, Lester declared, it would not have deserved “more than a mention in a reviewers’ roundup.” Little Man attracted little other attention and was swiftly consigned to the footnotes of Baldwin’s oeuvre as a head-scratching curiosity at best and a jejune mistake at worst. But it intrigued Boggs, who discovered it in 1996 at Yale’s Beinecke Library and was initially told by David Leeming, who’d composed a 1994 biography of Baldwin, that Cazac was likely dead. Nevertheless, Boggs sought out Cazac and left messages at several arts organizations in France. Then, one day a few months later, the phone rang in Boggs’s Brooklyn apartment. Astonishingly, Cazac was on the other end. “I heard you were looking for me?” the artist said. He met the elusive Cazac in 2003, two years before the latter’s death, becoming the only scholar to have interviewed Cazac about his artistic collaboration with Baldwin. Re-read today in light of the contemporary resurgence of interest in Baldwin’s novels and essays, particularly his meditations on black English and police brutality, Little Man, Little Man brings to life many of Baldwin’s arguments as it dissolves rigidly drawn lines between children’s and adult literature.

Advertisement

It is telling that TJ’s story could take place—even in its darker moments—almost unchanged today; America’s reflection, cracked and held up on a stand the color of dried blood, has changed far less than some optimists would prefer to believe. This is most notable in an extraordinary early section. TJ describes frantic, sometimes violent, encounters between black men and the police, his language suggesting the commonplace character of these interactions. It begins by TJ comparing his block to what he has seen on TV and in movies of police chases, but quickly transitions into specific descriptions of his neighborhood, ending with the man the cops are after being “done for. He not going to get off this street alive. Sometime he running down the middle of the street and the guns go pow! and blam! he fall and maybe he turn over twice before he hiccup and don’t move no more. Sometime he come somersaulting down from the fire-escape. Sometime it from the roof, and then he scream.” TJ speaks with a disquieting specificity and bluntness, as if such events are all too familiar to him. A black child is often forced to grow up early, Baldwin suggests, disabused of notions that children from more privileged families may cling to, such as the idea that police are there simply to protect you.

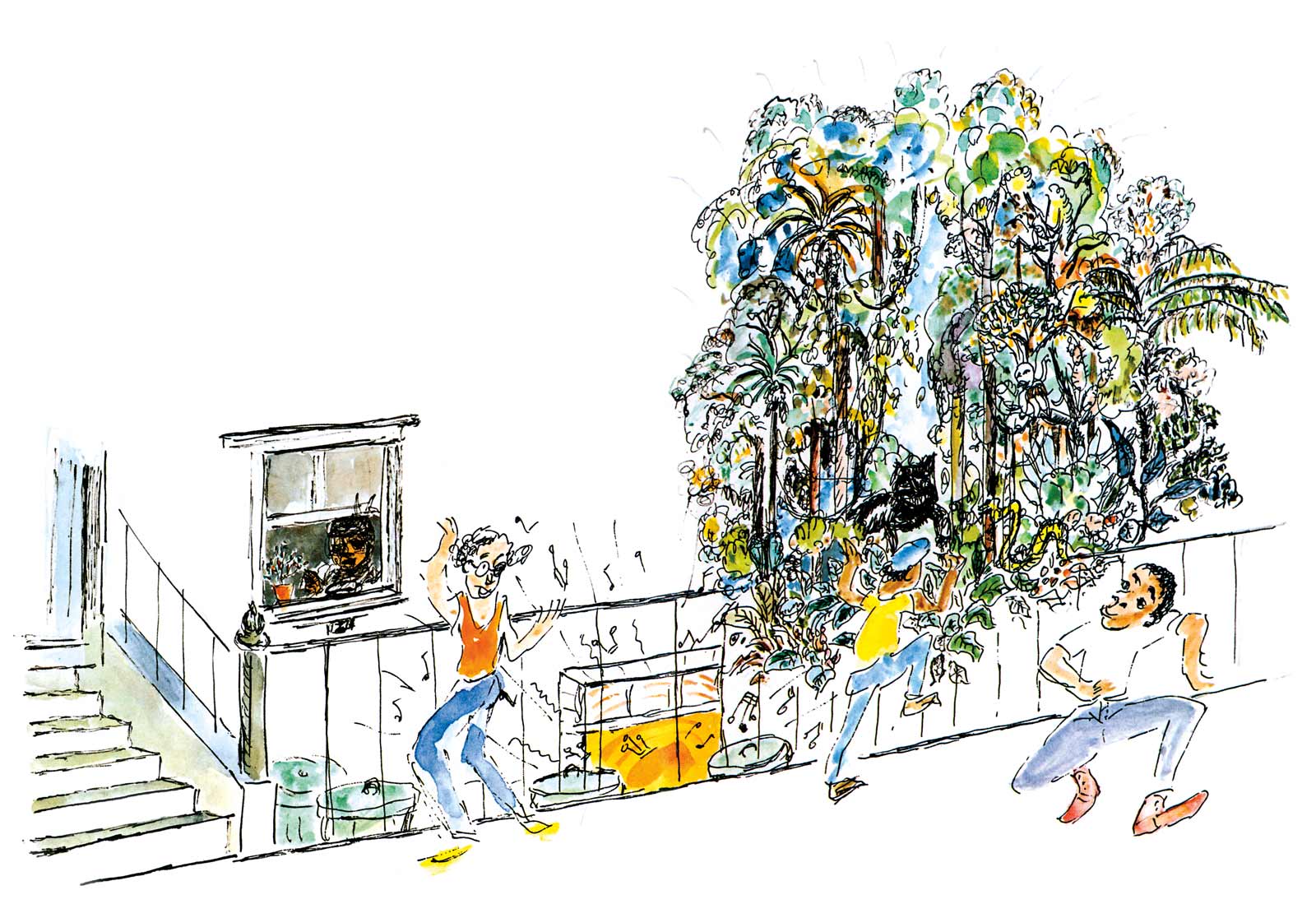

Yet TJ is still a child, and at the end, when one of the neighbors, Mr Man, makes a pointed comment suggesting that his wife, Miss Lee, has consumed all the gin in the house and should go back in an institution—seeming to imply that she is an alcoholic—TJ does not seem to understand. He senses the tension and is “more scared than he ever been before, and he don’t know why.” But when Blinky, the wisest of the bunch, begins to dance to music, they all start to laugh and dance as well—even Mr Man and his wife. There are things the kids can afford to learn later on; for now, perhaps it is enough to revel, momentarily, in the joy of sound and movement.

*

Baldwin had met Cazac in Paris in 1959, by way of his mentor, the gay black artist Beauford Delaney, to whom Baldwin would, seventeen years later, dedicate Little Man, Little Man. Beauford was an early champion of Cazac’s art. With Cazac’s tousled russet hair, intense eyebrows, and iconoclastic personality, the enigmatic French painter also struck Baldwin immediately, becoming an indelible presence in Baldwin’s life. Cazac “was sometimes as exasperating as a boy of ten, and sometimes as inaccessible as a man on ninety,” Baldwin reflected in 1977 of his early impressions of Cazac. At the time, the artist was working on a series of brûlages, a technique developed by the French artist Raoul Ubac in which film emulsion is melted, creating swirls and whorls; Baldwin found himself entranced by the surreal, seemingly igneous creations. “They struck me with their violence, and, also, their depth,” Baldwin said. Cazac’s later art, which Baldwin praised effusively, “defines spaces by challenging it.”

The two became close. In 1974, Baldwin dedicated what I consider his masterpiece, If Beale Street Could Talk, to Cazac; in turn, the French painter named Baldwin his son’s godfather. Their interpersonal relationship, alongside Baldwin’s connections with other artists, will be described in more detail in James Baldwin: In the Full Light, a book by Boggs on Baldwin’s life, forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

At Baldwin’s rural home in France, they collaborated on the project that would become Little Man, Little Man. Cazac had never been to New York, much less to Harlem, so Baldwin supplied him with photographs of his family and a copy of The Black Book, an epochal 1974 collection of African-American history that included slave auction notices, images of lynchings, patents for black Americans’ inventions, posters of the so-called “Black Hollywood” films of the 1930s and 1940s, and more. Despite these records, when he started work with pencils and watercolors, Cazac found himself still struggling to envision that peculiar city an ocean away; as he told Boggs in 2003, he began to “imagine the unimaginable.” The result was a vibrant vision of Harlem at once recognizable and strange, with colors freely bleeding out of lines and proportions liable to shift from page to page, as if to suggest that reality itself for the book’s protagonists was just the same: never constant, sometimes beautiful, always brimming with the potential for grotesquerie and grandeur alike.

Advertisement

The images perhaps echo something that Delaney had famously taught a teenage Baldwin, when Delaney asked him to peer at a gutter and tell him what he saw. Nothing, Baldwin replied. Delaney asked him to look again, and then he saw what he’d previously missed: the reflections of buildings in the gutter’s oil puddles. The lesson was simple but profound: look again, and you may see more. “Little Man, Little Man is [Baldwin and Cazac’s] effort to enact Delaney’s lesson,” Boggs said to me, so as to “revalue images and experiences deemed ugly or marginal by dominant culture.” Cazac’s dreamlike art does just this, seeking, through its rich colors and salmagundi of both smiling and brooding faces, to capture a nuanced vision of black childhood that, alongside Baldwin’s text, makes Little Man, Little Man stand out as utterly unlike anything in Baldwin’s corpus—or, even, American literature more broadly—that came before or after.

*

In a famous 1979 polemic on language, “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?,” Baldwin argued in The Times that “language is… a political instrument, means, and proof of power.” Black English, Baldwin wrote, had, through the “alchemy” of slavery’s horrors, “come into existence by means of brutal necessity,” and its continued existence bothered white Americans, in Baldwin’s eyes, as it threatened to convey, through its origins, uncomfortable truths many of them would rather ignore. “It is not the black child’s language that is in question, it is not his language that is despised,” he wrote near the end. “It is his experience.” This holds special significance for Little Man, Little Man, which was not only unapologetically written in vernacular, but also held up a mirror to white readers in particular by revealing, in its soft yet sharp brushstrokes, a vision of a world in which no black American, child or adult, is shielded from the dangers of institutionalized racism. But the mirror also captured black Americans in moments both quotidian and tender. Baldwin resisted stereotyping by showing a range of African-American experience; TJ’s world could be as frightening as it was ludic and loving.

The tender scenes are worth remembering. Baldwin is well-known for his fury; less often referenced are the wonderful moments in his work when his subjects get to be happy, get to love, get to dance. To be sure, with a searing sermonic fire, Baldwin—who had been apprenticed as a preacher at a young age, and, despite his adult agnosticism, never lost the cadences of the pulpit—rained upon the bigotry of America in his work. And yet, for all the threats surrounding TJ and his friends, some of which they understand and some they do not yet, the bad things lurking in shadow and light, there seems something quietly redemptive about one of Baldwin’s final works ending with a glimmer of pure, simple rapture.

Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood by James Baldwin and illustrated by Yoran Cazac is published by Duke University Press.