In A Tale of Love and Darkness, the 2002 novel-cum-memoir that, his obituarists agreed, was surely Amos Oz’s finest literary work, the Israeli laureate, who died in the last days of 2018, wrote these words:

When I was little, my ambition was to grow up to be a book. People can be killed like ants. Writers are not hard to kill either. But not books: however systematically you try to destroy them, there is always a chance that a copy will survive and continue to enjoy a shelf-life in some corner of an out-of-the-way library somewhere in Reykjavik, Valladolid or Vancouver.

Most of Oz’s admirers in Israel and around the world, those who long assumed that Oz was just a year or two away from a Nobel prize, would, I suspect, nominate the exquisite, elegiac Tale as the book best suited to incarnate Oz’s spirit, in accordance with his childhood wishes. It tells the story of his early years in the Jerusalem of the British Mandate, where he was raised by a librarian father whose head was forever buried in pages and footnotes, and a mother plagued by a depression that eventually led her to commit suicide when her son was twelve.

It is a magnificent book. Even so, it is not the vessel I would choose to carry my own memory of Oz. I would name instead In the Land of Israel, a non-fiction collection of reported essays originally published in the weekend edition of Davar, the now-defunct newspaper of the Israeli labor movement. The book recounted Oz’s conversations with Israelis and a handful of Palestinians, in Israel and on the West Bank, a few months after Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon had ordered the invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Much of what commends the book, which became an international bestseller, is obvious. It is brilliantly written, the novelist proving to be a patient, sharp-eyed reporter. He has a particular knack for direct speech. One chapter is devoted almost entirely to a monologue delivered by a man Oz calls only Z., an ultra-nationalist with feverish fantasies of a murderous Jewish militarism. Z. jumps off the page. Indeed, for those readers who found some of Oz’s fiction too brooding or too slow, In the Land of Israel fairly fizzes with energy: Z. might be one Oz’s most memorable characters.

But the reason why the book endures in my mind, more than three decades after I read it, does not relate chiefly to its literary merits. Its power was partly a matter of timing. I was sixteen when I picked it up, a child raised in a strongly Zionist household, the son of a mother who had been born in Petach Tikva in 1936, in what was then Mandatory Palestine. I had come of age in Habonim, a Jewish youth movement dedicated to the ideals of the kibbutz and steeped in Labor Zionism. I’d been fed stories of pioneers toiling in fields and orchards as they built a socialist utopia, one that would at last allow Jews to shake off two millennia of persecution and stand tall in the world.

In the mid-1980s, those dreams were colliding with reality. I’d seen the pictures of the Lebanon war on the news; I’d read about the massacres at the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, which, yes, were committed by Christian Phalangists but, as Israel’s own Kahan Commission had found, under the eye of the Israeli military. I had also traveled in Israel enough that it was becoming plain, even to my teenage gaze, that the comforting stories diaspora Jews had long told themselves about the country were not true. The discrimination, the inequality, the occupation: they were all too visible to be ignored.

The obvious response to all this was clear enough. I could have decided that the whole thing was a sham, that the Zionist enterprise was rotten from the start and that everything I’d been taught was myth and propaganda. Plenty of my Jewish contemporaries made precisely that move. But then, at that very moment, along came Amos Oz and In the Land of Israel.

The book did not tell me I was wrong to deplore the occupation or Israel’s mistreatment of the Palestinians. On the contrary, in that collection, and in later essays and articles—which I gobbled up—Oz regularly supplied fresh and damning evidence of where Israel was at odds with its own declared values. But he was firm that none of that contradicted a basic belief in Jews’ right to a home of their own. For all his denunciations of successive Israeli governments, for all his fluent and furious protests against wrong-headed wars and military brutality, his fundamental conviction in Jewish self-determination was not shaken.

Advertisement

Indeed, and this was what made such a powerful impression on my younger self, he refused to accept that there might be any contradiction between the two stances: he insisted that it was his very Zionism that led him to believe in the Palestinian right to independence. He supported the Palestinians not in spite of the fact that he was a Zionist, but because he was a Zionist.

One chapter in In the Land of Israel sees Oz visiting the offices of Al-Fajr, a Palestinian newspaper whose name means “The Dawn.” Oz reflects on the fact that in 1868, in Vienna, Peretz Smolenskin had founded a Zionist, Hebrew newspaper also called The Dawn. He quotes the opening page of the very first issue of Smolenskin’s version, which was full of dreamy talk of a people reclaiming its destiny and national self-respect. “It occurs to me,” Oz writes, “that it is surely not difficult to translate those words into Arabic.” Oz is telling us that the needs of these two peoples, Jews and Arabs, may not be identical but they are not so very different. If you believe in self-determination for one, then logic compels you to believe in that same right for the other.

In another chapter, Oz works through the moral reasoning that underpins his position. He visits the small—it was small then—West Bank settlement of Ofra. He listens to the settlers; then their leaders invite him to address an audience of forty or fifty of them at a public meeting, on a Saturday evening, once the sabbath is over. He lets us hear his own voice, uninterrupted. Deploying one of the trademark metaphors that were his sharpest tools of persuasion, he argues that the justness of the Jewish claim to historic Palestine is “the justness of the drowning man who clings to the only plank he can…

And the drowning man clinging to this plank is allowed, by all the rules of natural, objective, universal justice, to make room for himself on the plank, even if in doing so he must push the others aside a little. Even if the others, sitting on that plank, leave him no alternative to force. But he has no natural right to push the others on that plank into the sea. And that is the moral difference between the “Judaization” of Jaffa and Ramla and the “Judaization” of the West Bank.

In other words, the logic that makes the existence of 1948 Israel legitimate is the same logic that makes the post-1967 occupation illegitimate.

I remember reading those pages over and over again. I have returned to them in the years since. They represent as clear a statement of the liberal Zionist creed as I have read. They challenge the illiberal Zionist and the liberal anti-Zionist equally, for they insist that either all nations have the right to govern themselves or none does. The illiberal Zionist is urged to concede that right of self-determination to Palestinians, the liberal anti-Zionist is urged to concede it to Jews.

Oz’s version of liberal Zionism, expressed not only in In the Land of Israel but also in his later writings, media interviews, and public lectures, had three core components. I now understand that these elements were not confined in scope to the Israel–Palestine conflict, but were applicable elsewhere, if not everywhere—that they amounted to a world view.

The first was a belief in compromise, not just as a sometimes necessary evil but as an ideal in itself, to be cherished and admired. He once wrote that too often is compromise seen “as weakness, as pitiful surrender,” whereas, he explained, “in the lives of families, neighbors, and nations, choosing to compromise is in fact choosing life.” The opposite of compromise is not pride or integrity. “The opposite of compromise is fanaticism and death.” (Oz was fascinated, in both his fiction and non-fiction, by the figure of the fanatic, defined as the man “who wants to change other people for their own good.” When he and I met in 2016, Oz put it to me like this: “He [the fanatic] is a great altruist, more interested in you than in himself. He wants to save your soul, change you, redeem you—and if you prove to be irredeemable, he will be at your throat and kill you. For your own good.”)

The second principle was a demand—not always realized—for moral rigor, for moral judgements to be consistently applied. Oz was enraged by double standards, often faulting Israel’s Western and European critics for slamming Israel for behavior they readily forgave in themselves. He disliked lazy conflations and comparisons. He used to say that “He who fails to distinguish between degrees of evil becomes a servant of evil.”

Advertisement

I don’t pretend that Oz always got it right. Plenty on the left, inside and outside Israel, were disappointed when he supported the Operation Cast Lead offensive in Gaza in 2008–2009 and felt similarly let down when he described the repeat performance in 2014 as “excessive but justified.” But no one could deny that Oz wrestled with these judgments seriously and demanded of himself no less than of others a moral coherence. Mere tribal solidarity was insufficient to commend an action or policy: he would ask himself how he would react if the boot were on the other foot, if Israel was not doing but was being done to.

Which brings us to the third element of what we might call “Ozism”: a deep, even radical, empathy. Empathy is, of course, an essential requirement of the serious novelist. Oz’s day job meant that he was constantly imagining himself in the shoes of others. But that capacity is found less often in a political thinker. For Oz, however, it was the foundation stone on which everything else was built. Empathy runs through every chapter of In the Land of Israel, as Oz uses his imagination to identify with all those he encounters: religious settlers in Tekoa, angry Mizrahi Jews in Bet Shemesh, Palestinians in Ramallah, even Z. It’s the quality that enabled him to tell their stories, the quality that made him a natural storyteller. But it is also what made his hostility to fanaticism and belief in compromise a defining creed. Because he understood that one’s enemy is also, and always, a human being.

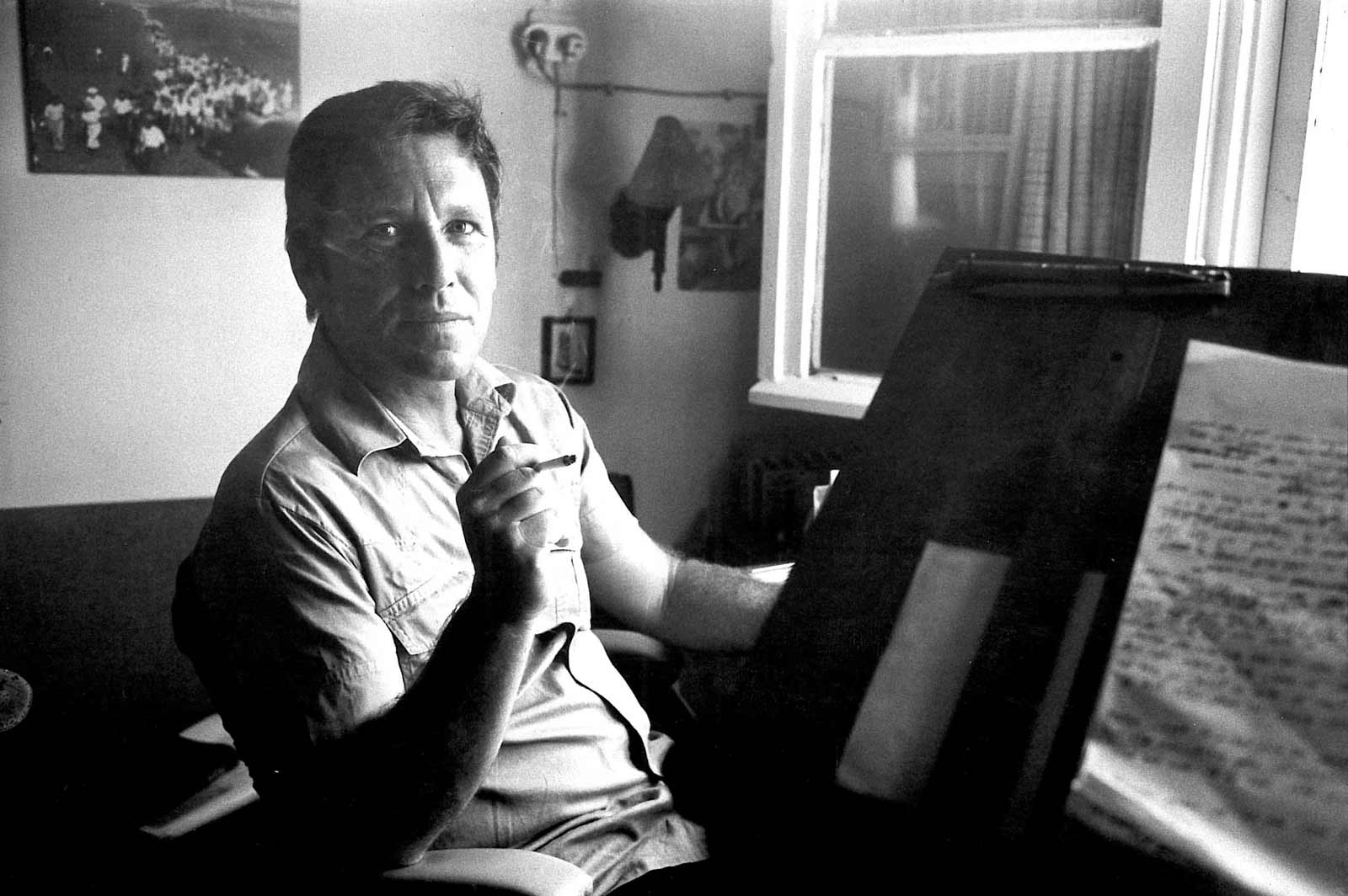

This, then, is why Oz was both revered and reviled as a prophet at home and garlanded with attention and prizes abroad. Of course, part of it was his rugged good looks, his astonishingly eloquent English, and his sonorous, broadcast-ready voice. But mainly it was his moral clarity and, deeper, that gift for empathy. Long after liberal Zionism had come to seem quaint in an Israel whose heart had grown harder, those qualities retained their value—none more so than the compassionate knowledge that people are frail creatures, frightened, flawed, and ultimately, like Oz himself, mortal.