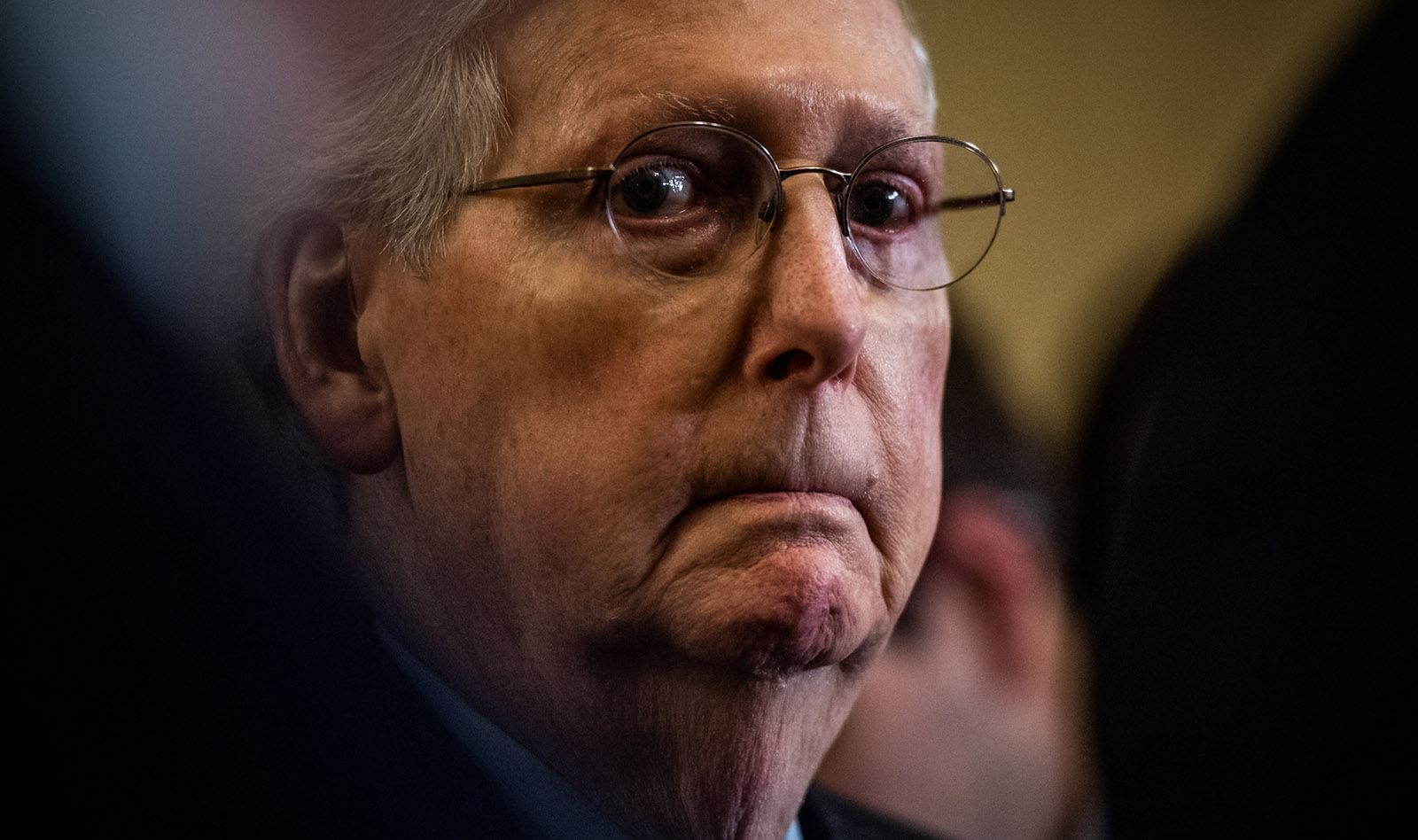

Some ten days ago, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell came to the floor of the United States Senate to unveil a bipartisan deal that would avert another shuttering of the federal government. Two weeks after the longest shutdown in US history, McConnell announced that President Trump would sign a government funding bill that pointedly did not include the billions he had petulantly demanded for his beloved border wall. But there was a wrinkle: Trump would, said McConnell, announce a national emergency, which would allow him to transfer money toward wall construction.

It was an abrupt flip-flop for McConnell, who weeks earlier had spoken out publicly against Trump taking such a step. For a man for whom serving in the Senate—and becoming majority leader—had been, according to Alec MacGillis’s biography of McConnell, “the dream… [he] had had been revering since he was a boy,” it would seem a particularly difficult concession of the congressional prerogative for him to make.

The most basic and powerful function of Congress is the power of the purse. The executive branch can only spend money that Congress authorizes and appropriates. In endorsing Trump’s power grab, McConnell was offering his explicit support for a move that strikes at the heart of Congress’s institutional prerogatives.

But if there is one defining characteristic of McConnell’s more than three decades in national politics, it is the prizing of political expediency over integrity, ideology, and any other impulse that should define public service in a representative democracy. For McConnell, as for the president whom he has repeatedly enabled, winning is the only thing that matters. All other considerations are secondary to that goal.

Writing for the Review last fall, the American historian Christopher R. Browning said of the Senate majority leader, “if the US has someone whom historians will look back on as the gravedigger of American democracy, it is Mitch McConnell.” In Browning’s view, McConnell is not dissimilar from the German conservative politicians, who in the 1930s brought Adolf Hitler to power, “thinking that they could ultimately control [him] while enjoying the benefits of his popular support.” With Hitler as Chancellor, the conservatives saw their fulsome policy agenda enacted: rearmament, suspension of civil liberties, the outlawing of the Communist Party, and the abolition of labor unions, among other moves. But as they would later find out, controlling the monster they put in power would be something else altogether.

Over the past two years, McConnell has made a similar pact with the devil (albeit a lesser fiend). He helped Trump pass a huge tax cut that disproportionately benefits the wealthy and he’s rubber-stamped Trump’s conservative picks for the federal judiciary, all the while looking the other way at Trump’s assaults on democratic norms and his authoritarian impulses.

Indeed, as alarming as Browning’s comparison might seem, it doesn’t quite do justice to the malign impact that Mitch McConnell has had on modern American politics. No politician has done more to weaken American democracy and undermine the nation’s most basic norms than McConnell. Nor is any politician more responsible for Trump’s rise to power. All of it has been in pursuit of the narrowest, most parochial goals.

What separates McConnell from other destructive political actors, such as former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and his fellow congressional Republican revolutionaries, or President George W. Bush and his vice president, Dick Cheney, is that McConnell’s political actions are unmoored from ideology and policy. For McConnell, politics is fundamentally about accruing political power for the sole purpose of accruing more political power.

In this, McConnell contrasts with his co-congressional enabler of Trump’s presidency, the former Speaker Paul Ryan. Ryan, too, looked the other way during Trump’s constant acts of political degradation because the man served as a means to political ends—tax cuts and the starving of the American welfare state. Those have been goals of Ryan’s seemingly from the moment he paged through a copy of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged at a young age. For McConnell, though, the means are the ends.

It wasn’t always thus. McConnell came of age in national politics at a time of intense turmoil within the Republican Party, as the rise of conservative ideologue Barry Goldwater threatened the long-standing control of the party by its moderate wing. At that time, McConnell sided with the moderates. As a young Republican activist, he supported civil rights legislation, which Goldwater famously opposed in the US Senate, and even counted himself as a backer of legal abortion.

As the years went by, however, and conservatives increasingly won the battle for control of the party, McConnell tacked with the political winds, embracing conservative positions that he had once inveighed against. Since McConnell’s overarching political aim had been to become a member of the Senate and wield power within it, concessions to political expediency would be required.

Advertisement

Yet what is perhaps most interesting about McConnell are not the positions he shed during his political rise. Rather, what separates McConnell are the positions he has publicly embraced. To the extent that McConnell has been defined by any single policy, it is campaign finance reform—and his implacable opposition to it.

During the 1990s, as Democrats and Republicans coalesced around legislation that would reduce the corrosive impact of money on national politics, McConnell decided his political future lay in going in the other direction. He became the most prominent voice in Washington extolling the salutary value of campaign money. This, too, ran in contrast to his earlier views. In 1973, he had written an op-ed for the Louisville Courier-Journal in which he called for “truly effective campaign finance reform,” which meant limits on contributions, full disclosure for donors, and a ceiling on the amount of money any candidate could spend.

But as the challenges of campaigning for political office became evident, his position on campaign finance evolved, toward stances that aligned with the GOP’s fundraising advantages. Many in the GOP caucus that felt politically constrained in publicly opposing such good governance reforms, but privately opposed efforts to limit their fund-raising. McConnell became their public spear-catcher.

McConnell seemed almost to relish the anger his positions engendered. When reformists began referring to him as Darth Vader, he appeared at a press conference toting a light saber. In playing this part, McConnell earned the gratitude of his fellow Republicans, something that would pay off when he sought to become the party’s leader in the Senate. McConnell would adopt a similar position in 2009 after Barack Obama’s inauguration. He became the public face of opposition to Obama’s policies, as he expertly wielded the Senate’s limitless tools for obstruction and delay to block the new president’s legislative goals. In his willingness to again play the role of villain, McConnell displayed a unique understanding of how modern American politics works: the more liberals hated him, the more Republicans loved him.

Beyond that, McConnell shrewdly exploited the inattention of voters and the media’s slavish devotion to bothsidesism. His constant efforts to obstruct Obama’s agenda surely enflamed Democrats, but for most voters, who barely followed the day-to-day goings-on in Washington, all they saw was ever-constant gridlock. It might have been McConnell’s flagrant and promiscuous use of the filibuster that killed legislation with broad support but rarely did McConnell’s role as the architect of obstruction get the attention it deserved. For most voters—and for a largely uncritical media looking to achieve “balance” and fairness by splitting the difference between the two parties—it was a pox on both houses.

McConnell’s obstructionism on spending bills, unemployment insurance, assistance to state government, even veteran’s benefits, undermined the recovery from the Great Recession, and purposely so. The worse the economy was doing, the more likely voters would blame the party in power—namely, the Democrats. As MacGillis pungently puts it, McConnell’s nihilistic strategy was to “wait out America’s hopefulness [about an Obama presidency] in a dire moment for the country until it curdles to disillusionment.” The more Washington looked dysfunctional, the more it played into McConnell’s hands.

Of course, this didn’t fully prevent Democrats from achieving some notable successes. They passed a stimulus measure in 2009 that, while not as large as necessary for the crisis at hand, blunted the worst effects of the recession. In March 2010, Democrats accomplished the long-standing liberal goal of enacting comprehensive health-care reform. Although McConnell’s determination to stop any Republican from supporting the measure meant that the GOP could play no role in shaping the legislation, he was bargaining on the political upside being a deeply unpopular bill that, to GOP partisans (and plenty of other voters), would appear to be a case of Democrats’ ramming their policies down the throats of the American people.

There was, however, a political downside to McConnell’s unrelentingly rejectionist approach: it played directly into the hands of the extremists in his own party. Indeed, the Senate GOP’s inflexible opposition to Obama, the venomous attacks of Republican partisans (including questions about Obama’s birthplace and religion), and McConnell’s declaration that “the single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president” gave oxygen to the fledgling Tea Party movement. In 2010, the victory of extremist conservative Republicans in party primaries would help cost McConnell the chance to become majority leader in the Senate (postponing that outcome until 2014).

Advertisement

But none of that dissuaded McConnell from the path he had laid out. Rather than fight the extremists who had declared war on the Republican establishment (epitomized by McConnell himself), he cultivated them. By doing so, he gave political oxygen to the most radical and extreme voices within the conservative movement, laying the groundwork for Trump’s rise within the GOP in 2016. As the election approached, that rise received a crucial assist from McConnell’s decision to downplay links between the Trump campaign and Russia and warn the Obama White House “that he would consider any effort by the White House to challenge the Russians publicly an act of partisan politics.”

That year also, McConnell carried out what he now considers his crowning achievement: preventing the Senate’s consideration of Obama’s pick to replace Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court, Merrick Garland. “The decision not to fill the Scalia vacancy,” McConnell recently told The New York Times, is “the most consequential thing I’ve ever done.” Indeed, McConnell has spoken approvingly of the part that blocking Garland and putting the Supreme Court on the ballot played in helping elect Trump. Doing so has also enabled McConnell to achieve his other long-standing political goal of remaking the federal courts in a conservative image.

Here again, it’s not about policy for McConnell. Judges matter to conservative voters, and so they matter to McConnell. That these same conservative judges can be relied on to limit voting rights and issue decisions that ensure the steady flow of money into Republican campaigns is merely the icing on the cake. It is yet one more path to ensuring Republican electoral dominance.

That McConnell has, in the process, undermined the legitimacy of the Supreme Court and turned it into another area of partisan conflict in American political life seems to be of little concern to him. Indeed, McConnell appears largely uninterested in the consequences of his actions on the nation’s fractured politics.

Perhaps the most telling quote from McConnell’s recent interview with the Times was when he was asked about Christopher Browning’s comparison of him to the old conservatives of Weimar Germany. His answer is telling:

I think to expect Republican elected officials not to try to achieve as much as they possibly can, that they’ve always been for, out of pique over presidential behavior, is nonsense… He got elected… So critics like that expect us all to just join them in a huff and do nothing? Really? I think my responsibility as the majority leader of the Senate, in a Republican administration, is to achieve as much as I can for the American people along the lines that I’ve believed in my entire life.

But what beliefs? A formerly moderate, pro-civil rights, pro-abortion rights, reform-minded politician has enabled a president who not only has set back race relations, but has also packed the Supreme Court with conservative, pro-life judges. A senator who once railed against budget deficits and alleged foreign policy weakness in Democratic presidents has advanced a trillion-dollar deficit and a president who appears to be compromised by a foreign power. An institutionalist who has sought to protect the Congress’s prerogatives as a co-equal branch of government has allowed Trump to chip away at them with barely a demurral.

The sole purpose that animates McConnell makes doing what he “can for the American people” at most secondary or tangential; there is only the will to power. He is a remorselessly political creature, devoid of principle, who, more than any figure in modern political history has damaged the fabric of American democracy. That will be his epitaph.