“Of course, we had an open marriage.” The cameras were rolling. I could smell my mother’s thick, expensive perfume. It was one of those very gray, cold New York City winter days, dark at 4:30.

My most recent slate of maternal problems had started with the death of Nora Ephron at seventy-one. She had been my mother’s heartbreak riddle: the novelist who had gone on to make it in Hollywood while still writing for The New Yorker. I completely understood the feeling; I would have been incredibly jealous, too, had I been Nora’s peer. It was made worse by the fact that, though incredibly attractive, Nora also wrote pieces about the deficits in her physical appearance like “I Feel Bad About My Neck.”

Nora’s eldest son, whom I had known only very slightly growing up but who had far surpassed me career-wise, had made an excellent documentary called Everything Is Copy about his mother’s life. This had somehow made my mother feel that the thing her life lacked most was a documentary about her life. I didn’t realize that was what she wanted until a German filmmaker was already following her around. Then between awkward moments of learning new details about my parents’ relationship on camera, it occurred to me that my mother might have been hoping that I would make a documentary about her—but unlike Nora, she hadn’t died tragically. She was very much alive.

“I’m sorry, what?” Even from where I was sitting on the sofa, I could sense that the German filmmaker appeared giddy with this revelation. We did make good content—we always had. And that content had spilled over everywhere into the memoir I was writing that was not directly about her, but when you’re the daughter of a powerful woman like that everything is “about her,” even the things that aren’t “about her” are, in fact, about her. I didn’t need to make a documentary about her, in that sense, because everything I did was a documentary about her. My life sometimes felt like a footnote to hers.

“We had an open marriage,” my mother said again, waving her hand as she took a sip from her coffee. I knew all about open marriages because both sets of my grandparents had had them, though what was an open marriage and what was just having a promiscuous spouse seemed to have a very blurred demarcation line. My grandfather, Howard Fast, admitted to cheating on my grandmother on page forty of his memoir.

“What?”

“I was sure you knew.”

Perhaps, in a normal family, this revelation would have created a stir or a crisis, but my father was my mother’s third husband and my grandparents had all had lovers and my mother wrote the seminal “leave your husband blow up your life” novel of the Seventies, and so there was a sense in which these things were kind of okay.

Mom was not apologetic. And I was actually a little surprised I didn’t know. I knew a lot of gross details about my parents’ sex life, including the absolutely hair-raising fact that they’d had a threesome with a “famous(ish)” 1970s feminist who now bore a striking resemblance to MC Hammer.

I tweeted the revelation immediately because it was funny and painful and needed to be defused—and because my mother had spent her entire life writing about me, as the redhaired daughter (except for one novel where I was twins), and it had affected my expectations of privacy. Also, I was addicted to Twitter.

Perhaps it was wrong of me to assume that the self-proclaimed queen of erotica wouldn’t have an open marriage. After all, she’d written Fear of Flying, the book that launched a thousand affairs and gave women of the Seventies the right to fuck whomever they wanted or leave their husbands or join a primal scream group or go live in a commune. I was very much not a product of that world, and while I understood some aspects of that particular paradigm shift for women, I didn’t really understand my mother’s cultural significance to these women: these starry-eyed women who spotted her in restaurants or foreign hotels, these women who came up to her and touched her dreamily and told her that her book had changed their lives. I had lived a different shift.

Later, my mother took the flustered German filmmaker to see her elderly shrink and I snuck into the bedroom and called my father who had recently moved to Palm Springs, California. “Did you know that you and mom had an open marriage?” I asked him. We had a sort of jovial relationship; we shared the experience of having a crushingly powerful parent and it was a sort of bond.

Advertisement

“Oh, is that what she’s calling it now?”

*

They met outside the Beverly Hills Hotel, in the driveway, under the pink awning and green palm trees. It was 1975. My father, Jonathan Fast, was the only son of a famous Communist novelist, Howard Fast.

Howard was famous the way writers are famous, which is to say not really famous, not famous like a movie star or a person you’ve seen on TV. People might look at him and think they knew him—perhaps they were a very distant cousin or maybe, if they were an avid reader, they’d be able to place the face. Mostly, though, people would have this strange kind of déjà vu response around my grandfather, as they later would around my mother. “Don’t I know you?” and then an awkward stilted conversation would take place that would involve embarrassment on both sides.

My grandfather can be explained in the empty spaces, the ways in which he differed from the mean. Sometimes, in memoirs, children of famous people lionize their parents and grandparents. I wasn’t taught to write like that. My mother always told me that you were supposed to do as Hemingway (everyone’s worst husband) once said: “Sit down at the type writer and bleed.”

It occurred to me recently that my grandfather might have actually been trying to have an affair with my mother. My mother has never implied this in any way, but she often leaves out the most interesting, the most critical, details.

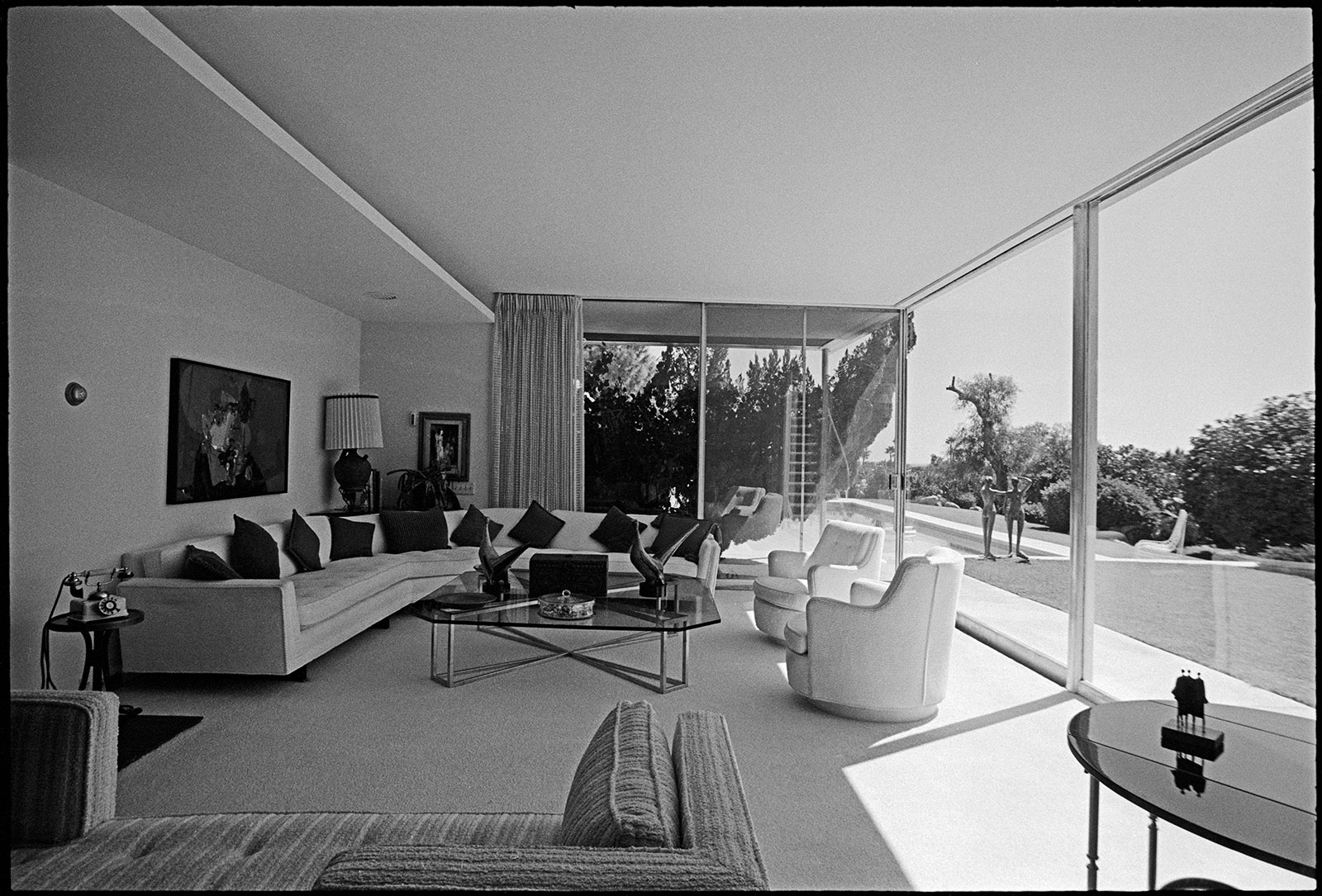

In any case, my grandfather, Howard, and his long-suffering wife, Bette, had offered to make a party for my mother after the publication of Fear of Flying. My grandparents were living behind the Beverly Hills Hotel in a house that—like all houses in Hollywood—had once belonged to Elizabeth Taylor. So, one day, Erica boarded a big Pan Am jet and headed out to the coast. She was at the time married to the shrink from Fear of Flying (Allen Jong) and living in her grandfather’s New York apartment at 20 West 77th Street.

When I was young, my mother loved to tell me the story of how she met my father. Howard Fast himself was supposed to pick her up to go to the party, but then the bartender didn’t show and so my grandfather sent my father. She says that he saw her picture on the back of her poetry book and said, “I’m going to marry that woman.” My grandmother informed him that she was already married.

It’s funny but I never realized until recently that my mother was still very much married to her second husband when she met my father. It’s stranger still because my mother enjoyed telling me the story of how she had gone to Haiti for a quickie divorce, but somehow, I never made the connection between her marrying my dad and the quickie divorce. The idea of my mother going to Haiti by herself to get divorced from a boring doctor sort of thrilled me. She had stories of the sleazy divorce lawyer who tried to sleep with her.

Either way, it was always sold to me as one of those great 1970s love stories, the son of a once-jailed Communist hero (and serial philanderer) and the young, blonde, second-wave feminist who was six years his senior. It was feminist because she was older. It was glamorous because she was famous (writer famous), and it would have a magic ending because things in Hollywood always did—after all, they met on a car ride to a party in a pea-green MG and fell in love, she had a bestselling novel and it was only a matter of time until he had one, too. They would move to Malibu to raise children, live a perfect hippie life against the backdrop of the Pacific Ocean.

*

Except none of that happened. My mother got pregnant in Paris in 1977. They decided not to live in Malibu on the Pacific Coast highway in a small house next to a heavy metal band. They decided to move back to the East Coast. Kids who grow up in LA are nuts, my mother declared. They bought a modern-style house not far from the city in a hippie suburb. They promised each other never to marry but soon they did. It was a small, secretive wedding in Weston with four guests, one of whom would later go to jail.

My grandparents Howard and Bette Fast were not invited; they were devastated. Pictures of the wedding smell—at least metaphorically to me, years later—of marijuana. I imagine they ate carrot cake. A few months later, I was born, with red hair. I wore a bib that said “Liberated Woman.” My birth was, strangely, featured in People magazine. The black-and-white picture of the three of us was the culmination of second-wave feminism: a thirty-six-year-old career woman able to have it all—kids, husband, and fame.

Advertisement

Six months later, my mom had a drug overdose at a Mexican-themed party.

“I had made margaritas with fresh lime juice,” my mother said, as we talked on the phone. It was my eldest son’s fifteenth birthday and I was lying in bed trying to write. Teenaged boys had taken over my apartment but I was focused on writing about the dissolution of my parents’ marriage in a humane and yet accurate way (though perhaps those two things cannot co-exist).

Many facts had become confabulated in my mind—such as the idea that my mom had a drug overdose at her fortieth birthday party. “So, it was not your fortieth birthday party?” I asked her, careful to not push too hard on the parts of the story that were still sore.

“No, you were six months old and I was making these margaritas with fresh lime juice. It was a Mexican-themed party. I made tortillas and we still have the tortillas press, somewhere. Fresh tortillas right off the press.”

Since my stepfather (my mother’s fourth husband) had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s a few months earlier, my mother had picked up this weird habit of emphasizing the least important part of the story. My stepfather’s Parkinson’s diagnosis had shocked my mother into some kind of abject panic that had made the world almost nonsensical to her. The lime juice hardly seemed the most important point of the story, but the idea that my stepfather was deteriorating and wouldn’t always be able to care for her had made these details somehow more important.

“Can you tell me more about the drug overdose?” I was cautious because I didn’t want her to think I was writing anything mean about her. But, of course, I knew the truth, which is that everything is devastating and everything is copy.

“There was a PR girl who was working on Fanny. I was just about to publish Fanny, and I had had too much tequila. Betsy—her name was Betsy and she was a drug addict.” This line stung me because I’m twenty-one-years sober and was very much a drug addict in my period of active use. Also, I wasn’t sure why mom kept returning to that detail: Why would Betsy’s being a drug addict make my mom more or less culpable? I said nothing, though, because I didn’t want to distract her more than she already was distracted. “If I had known she was a drug addict… but no one told me she was a drug addict.”

“Okay.”

“My editor from Playboy was there. I had a Playboy interview. She had interviewed me in Malibu before we moved back to the East Coast.”

“Mom, focus.” I was gentle; usually, I’m more pointed, a little hostile even. Mothers allow us this shorthand, or perhaps it’s abuse.

“She gave me two blue pills. I took them. I passed out. And Helen Singer Kaplan and her son were there, they walked me around. They kept me moving. They told me not to go to sleep. They kept me up. They saved my life. Thank God for them. Otherwise, I would have been dead.

“If I hadn’t had those margaritas, obviously none of that would have happened. It was the fresh lime juice.”

“Oh.”

“And, I wasn’t nursing you anymore, and I went into your room the next day and I picked you up. I always did that in the morning.” Left out here is the round-the-clock childcare that I had, which is not said with any kind of judgment as I myself also enjoy a fair amount of childcare. Mom went on:

“I thought, What am I doing? What is wrong with me? And I never did drugs again, except for sometimes pot—but only in Europe. No one told me that PR girl was a drug addict. It was the fresh lime juice in those margaritas.”

It wasn’t the fresh lime juice.

*

By the time I was three years old, my parents embarked upon the hippie version of irreconcilable differences. As a consequence, I don’t remember them ever being together, which is probably a good thing. I do remember them fighting and maligning each other to me, but I’m forty and when you’re forty you’re supposed to be over your childhood. After all, you survived it; why relitigate it?

At forty years old, you’re supposed to be over your childhood. You’re not supposed to be haunted by that loneliness you just can’t quite shake. You’re not supposed to look at your kids’ happy childhoods and feel just the slightest bit empty. You’re not supposed to wonder why it still sometimes hurts even after all those years of sobriety and therapy.

Maybe you shouldn’t be bringing this all up again, maybe this is pointless surgery, but maybe everything is copy.