A few weeks ago, just before the dawn of the new year, I typed my Latvian national identification number into a crisp online database and watched as an index of more than 4,000 crumbling, yellowed index cards appeared on my screen. Some were marked with the telltale script of typewriters, staid and blotted, but most were covered in a sloping Cyrillic scrawl. All of them took the same bureaucratic form: alias, name, date and place of birth, category (“agent”), recruiter, and date of recruitment.

Alongside all these names, there was also a KGB phonebook, a counter-intelligence dictionary, a list of “freelance” personnel, and regulations for agency conduct and record-keeping. Together, these files amounted to a snapshot of the KGB’s internal workings in Latvia at the moment of the Soviet spy agency’s dissolution, a compendium of its secret informers, and all I had to do was click to download.

The cards were found piled in bags and briefcases in the agency’s Riga headquarters in 1991, after Soviet rule had dissolved. From then on, most of them have been kept under lock and key, first in a secure room in the Latvian parliament, and then in the Center for the Documentation of the Consequences of Totalitarianism. The fact of their existence, the betrayals they contained, and the rumors that slowly seeped out of the archive have haunted every post-Soviet government since.

“They have been part of the Latvian vocabulary since the 1990s, these ‘Cheka bags,’” Mārtiņš Kaprāns, a Latvian cultural historian, told me, using the colloquial term for the files, a reference to the original iteration of the Soviet security services.

Over the past several decades, Latvia’s parliament voted three times to open their contents to the public, and each time, it was thwarted by presidential veto. Finally, in 2014, with a new president in office, parliament passed a measure authorizing the publication of the “Cheka bags”—only after a scientific commission completed a thorough study of their content, but no later than May 2018. And so, in late December, the index cards were digitized and uploaded to the web for all to see, seven months behind schedule and twenty-seven years after the end of the empire that they were created to support.

My mother called to ask if I had heard the news of their release. (My family emigrated in 1988.) No one close to her had turned up among the cards, thank God, she said, but there were friends-of-friends, neighbors, acquaintances, teachers. Some she had always suspected, others she never would have guessed.

*

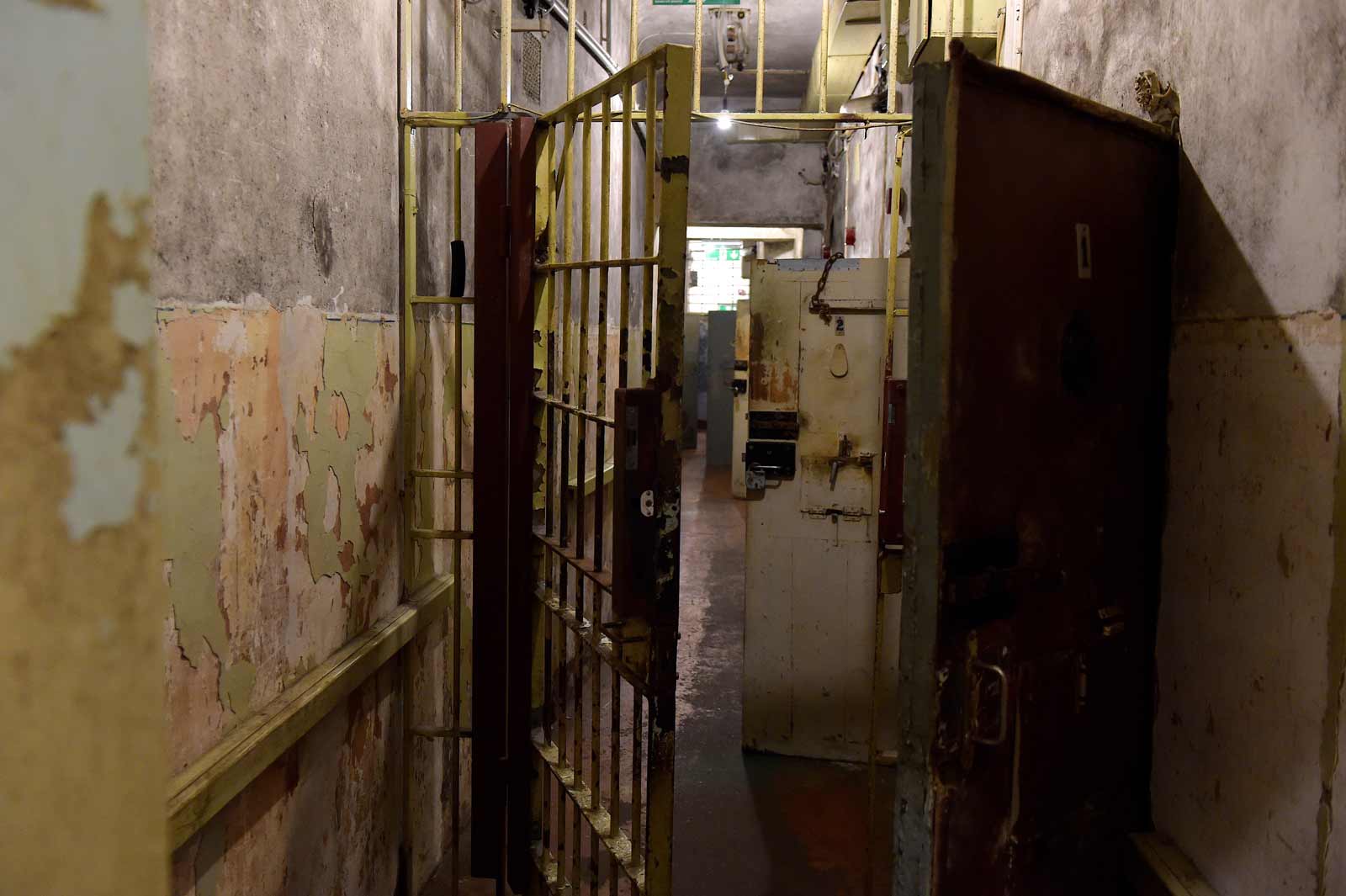

It was in 2015, on a tour of the old KGB headquarters, a decaying, vacant edifice known to locals as the “Corner House,” that I first encountered these files, or at least their myth. The building’s isolation cells, interrogation rooms, and execution chamber—used to kill prisoners only for a couple years, at the start of World War II—have been partially preserved, and the building had recently opened for tours as part of Riga’s yearlong stint as the European Capital of Culture. A month before my visit, a local artist had erected a statue of the Russian president in the courtyard, dressed in a suit and tie and pinned to a bright red crucifix. The tour guide told me that, despite the building’s once-grisly history, there had been talk of converting part of the structure into private apartments.

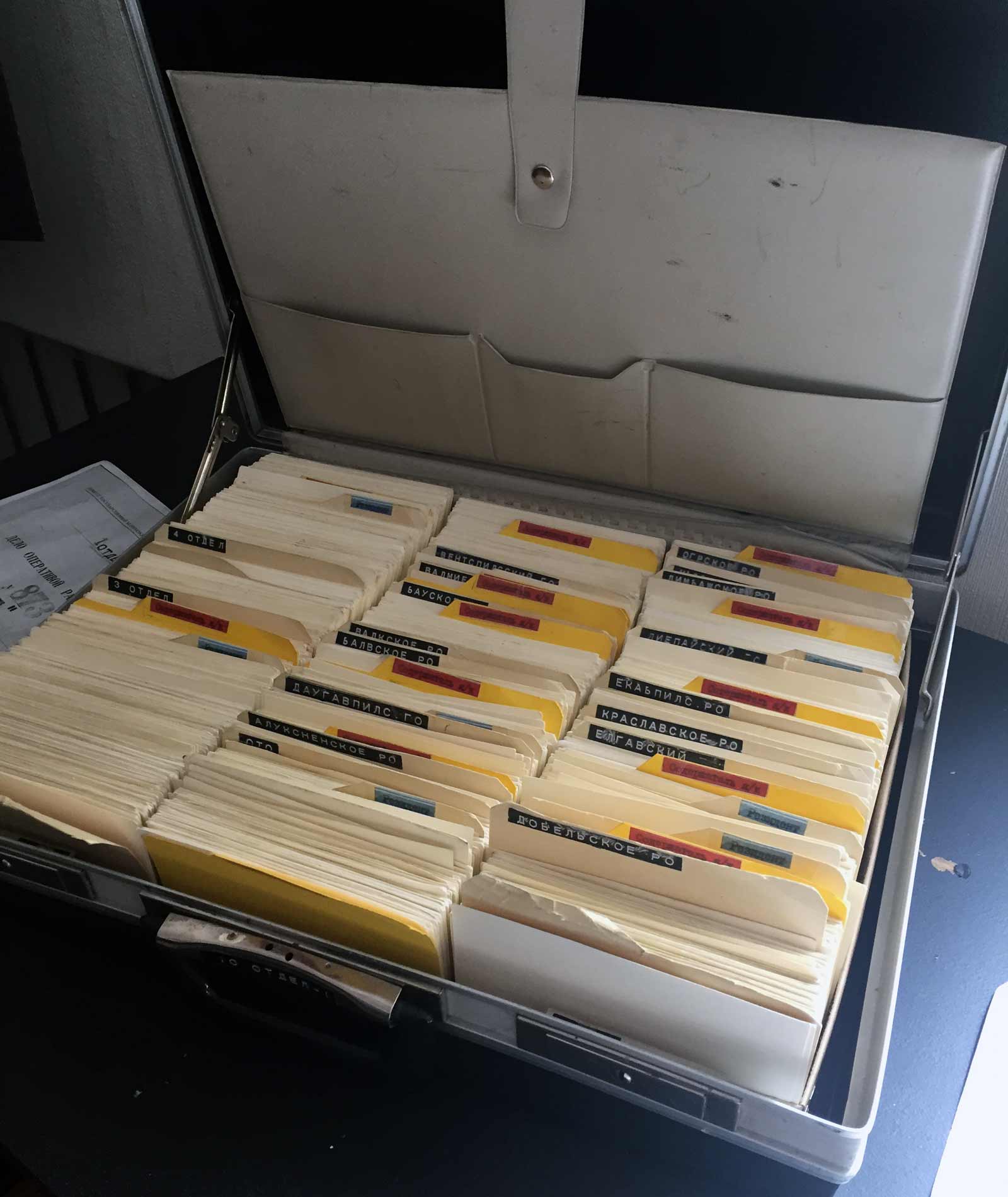

Toward the end of the exhibit, our group encountered a shoddy plastic suitcase, propped open to display its wares. It was stuffed full of index cards, some of which were brightly labeled with the names of Latvian cities. I found out that the suitcase was a loan from the Documentation Center, where the KGB Scientific Commission had recently begun combing through the archives. I emailed the chair of the commission, the well-known historian Kārlis Kangeris, to find out more, and we arranged to meet in the old city.

His work was not going well, he reported. Four members of his team had just been dismissed by parliamentary decree and the Ministry of Justice, he said, was obstructing the work of those who remained, blocking them from access to all the documents they needed. “They’re not interested in our research, what can I say?” he lamented. “They want to be silent, to have no one discuss it… These agent files, they say that they will cause a revolution in Latvia, but I don’t believe that. These people have had twenty-five years to think over their pasts.”

The commission’s work was hardly without precedent. In countries across the former Soviet bloc, decommunization policies have made other troves of KGB documents available, in full or in part. In Germany, citizens of the former GDR have long been able to request their own surveillance files; the Stasi files were published online in 2015.

In Latvia, the long process of decommunization was never fully completed, in large part, some claim, because the “Cheka bags” were stowed away so long. But that might now change: as far as this release goes, few Chekist collections are as comprehensive as the Latvian materials, which were posted online all at once, unmediated, with little annotation or historical explanation.

In 2016, a year after my original visit, I met Kangeris again, at Riga’s Freedom Monument, a soaring granite and copper obelisk that marks the city’s central plaza. He led me down the street, to where the commission had recently established a small office. His team was still experiencing some resistance to their work—“Many people in the files are still young, fifty or sixty years old,” he said. “They want to die as normal people”—but things were going slightly better. The new space meant that his researchers no longer had to convene at restaurants, and they had received some parliamentary assurances that they would be able to access the KGB’s electronic database, DELTA, containing thousands of agent reports.

“If you can get these materials, then you can see how the KGB operated over its final ten years,” he told me. “You will get the whole picture of Latvia.”

But that ambition was thwarted. The “Cheka bags” files provide a window into the workings of the Soviet security state, but not the “whole picture.” The 4,000 or so cards represent a fraction of the more than 24,000 KGB agents recruited in Latvia between 1953 and 1991. Although the commission is expected to publish portions of the DELTA reports later this year, they will be posted with redactions, unlike the cards. An unknown volume of KGB materials was transferred to Moscow before 1991, and the rest have been scattered: some documents were destroyed, supposedly mistakenly, at the Latvian Police Academy.

The dispersal of these documents, and the somewhat baffling contents of the files that survived, have led some to suggest that what the cards really depict is a system on the brink of collapse. “Because of the rapid changes that happened in the late 1980s, the KGB was simply not able to control the situation in the same way they used to,” said the historian Kaprāns, who was one of the original members of the scientific commission that examined the records before their release. “So, they recruited anyone, including the most influential people.”

This approach also provides a partial explanation to the open, and perhaps unanswerable, question of why these particular files, and not others, were left behind. Some say it was deliberate and malicious, to pit fellow-citizens against one another, while others, including the last head of the Latvian KGB, Edmunds Johansons, have maintained that it was because these were the least significant documents, not worth the effort of shipping out or even burning. Researchers have tried to parse the few distinguishing marks on the files: some are labeled for permanent storage, while others are marked with red diagonal script reading, “reserve for a specific period,” which is thought to refer to some future moment of national crisis and possible threat to the regime. But it is impossible to tell, from the materials currently available, what these local agents for the KGB actually did, if anything.

“They put everyone in the same sack, those who have the blood of partisans on their hands, and those at the other end, who had no idea that they were even considered agents,” said Indulis Zālīte, the former head of Latvia’s Documentation Center, who, for precisely this reason, spent decades campaigning against the public release of the files. His view is shared by many in authority, who, confronted with the question of whether it is better to have a partial and perhaps unreliable view of history, or none at all, opted for the latter.

*

It was supposed to be cathartic, this unveiling, a kind of national exorcism. One judge called it a “matter of hygiene,” to confront the past in this manner. For others, it was more aptly likened to the ritual cleansing of the ancient Romans, the “lustrum,” a purifying process that took place every five years, after the completion of the census. Public officials at the end of their tenure were forced to come forward, confess their sins, and repent. Through this ritual, the entire body politic would be renewed.

And Lustrum is, appropriately, the title of a new documentary about the long saga of the KGB archives by the director Gints Grübe and journalist Sanita Jemberga. It was released in November, just a few weeks ahead of the files themselves, as part of the country’s centenary celebration. The opening scenes show the KGB Corner House being renovated, a small army of workers patiently erecting scaffolding around its flaking façade. The camera follows the former longtime dissident Lidija Doroņina-Lasmane on a visit to the building where she was once interrogated. She strolls past the opened doors of former prison cells and peers cautiously inside.

Advertisement

“The last time they arrested me, they did not take me to the basement,” she says. “God’s law is that nothing stays hidden. Everything is revealed, and truth cannot be trampled into ground. It is the same with all these files.”

In another scene, Johansons gamely takes questions from the filmmakers from behind his old desk. “It’s like a hot potato in your mouth, understand—you can’t eat it, you can’t spit it out. That’s how it is with the files, and that’s how it’s going to be,” he tells them. “You can’t prove anything, so basically it’s like… fighting with windmills.” (Johansons died in 2017, not long after that interview.)

The film is a collage of historical footage and contemporary interviews that race forward and backward in time, telling the story of the nation through the discovery, suppression, and study of these files. Prominent cultural figures who show up in the Cheka bags appear on camera to explain themselves. Others recall how they were almost recruited: “This is a completely different and wonderful KGB,” the poet Māra Zālīte remembers one agent telling her, as he tried to cajole her into describing the activities of her fellow literary exiles.

Jānis Rokpelnis, another celebrated poet who publicly confessed, in 2017, to collaborating with the KGB only to find his name absent from the files, clings to the latent uncertainty of the archive, to all that it leaves unsaid. He does not regret his confession, he tells the filmmakers, because he could still take it back if he wanted to—it’s not too late to claim that it was all just a joke.

“After all of our interviews,” Grübe, the film’s director, told me, “I had this feeling that, since 1991, people more or less knew that their names were here in the archive. But they found a way, in their heads, to build stories around them. I don’t know if they believe them, but they all find a way to talk about it.”

*

Now that the files have been exposed to the harsh light of day or, in this case, the glow of a thousand computer screens, they have begun to take on a new life. Instead of igniting a revolution, they have brought on a slow, subdued kind of sadness.

“I would call it a partial freedom,” Jemberga told me. “It killed all the rumors, because now you can see who is in the files and who isn’t.” Few whose names are in the files have come forward to explain themselves—perhaps because only a small fraction of people know how they got there. “A massive cleanup of the soul in the sense that was expected didn’t happen,” she added, “but at least there is this partial freedom.”

The stories people told themselves about the past, about the lives of their friends and loved ones, have begun to corrode, and the effect of all this is felt more acutely in the country than in the capital.

“A woman from Latgale [a region in southeastern Latvia] called us three times, crying,” Indulis Zālīte told me. “Her father, who was already dead, was in the bags, and she couldn’t show her face in the church or at the store.”

“For some, individually, it is experienced as a tragedy, this opening,” said Kaprāns. So what was the point of it all? In one sense, the exposure of the Cheka bags will not change much—most of the people whose names are in the files have already retired from public life or are on their way out. “That means we are a little late,” Grübe told me.

But the more optimistic take is that it happened just in time. The last generation to experience Soviet rule is ceding power to its inheritors, young people in their twenties and thirties who were taught that they had the good fortune to grow up beyond the reach of this history. The hope is that publishing the documentary detritus of the KGB will act as a cautionary tale, preventing any similarly repressive surveillance apparatus from rising again. Kangeris’s scientific commission has even proposed a law to this effect, called the Law on Transparency and Preventing the Repetition of a Totalitarian Regime, which will authorize the publication of the personal files of members of the Latvian Communist Party, along with a vast array of documents from Communist committees, commissars, prosecutors, and more.

“The purpose of the draft law is to eliminate the possibility of the repetition of a totalitarian regime,” the proposal states. Reading it, one is struck by the quaint hope it expresses. If only all it took to make the past truly past, unreproducible and incomparable, was to pass a law declaring it so.