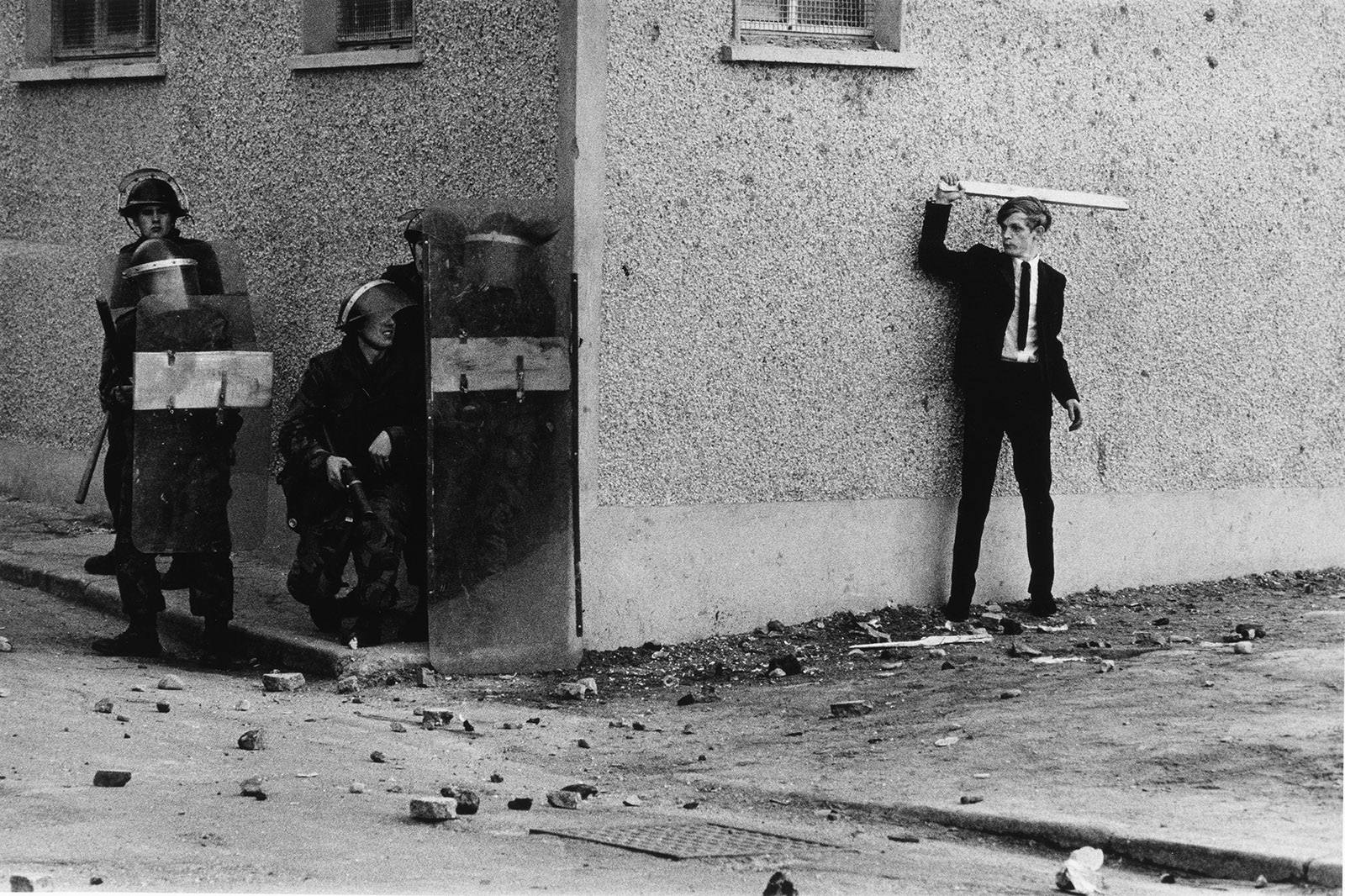

“People have a tendency to call me a war photographer. I hate that.” These words are murmured by a genial old soul at the start of the recent BBC documentary Don McCullin: Looking for England, but a visitor to the large retrospective of his photographs at the Tate Gallery might be puzzled by the statement. This great artist of the camera has spent the best part of sixty years if not looking for trouble, then certainly finding it—in Cyprus, the Congo, Vietnam, Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Syria. “War is hell” and “man’s inhumanity to man” could be the mottos of his life’s work; the exhibition is harrowing, and sometimes overwhelming.

His career began improbably. Sir Don McCullin, as he is now known since being knighted in 2016, was born poor in 1935, in what was then the depressed, even wretched corner of North London known as Finsbury Park. Today, the neighborhood is mostly gentrified and much prettified—though when McCullin revisits his childhood home in the BBC documentary, parts of it have evidently resisted that trend. Without much formal education, McCullin learned about photography, and especially about the dark room, of whose arts he became such a master, as a national service conscript in the Royal Air Force.

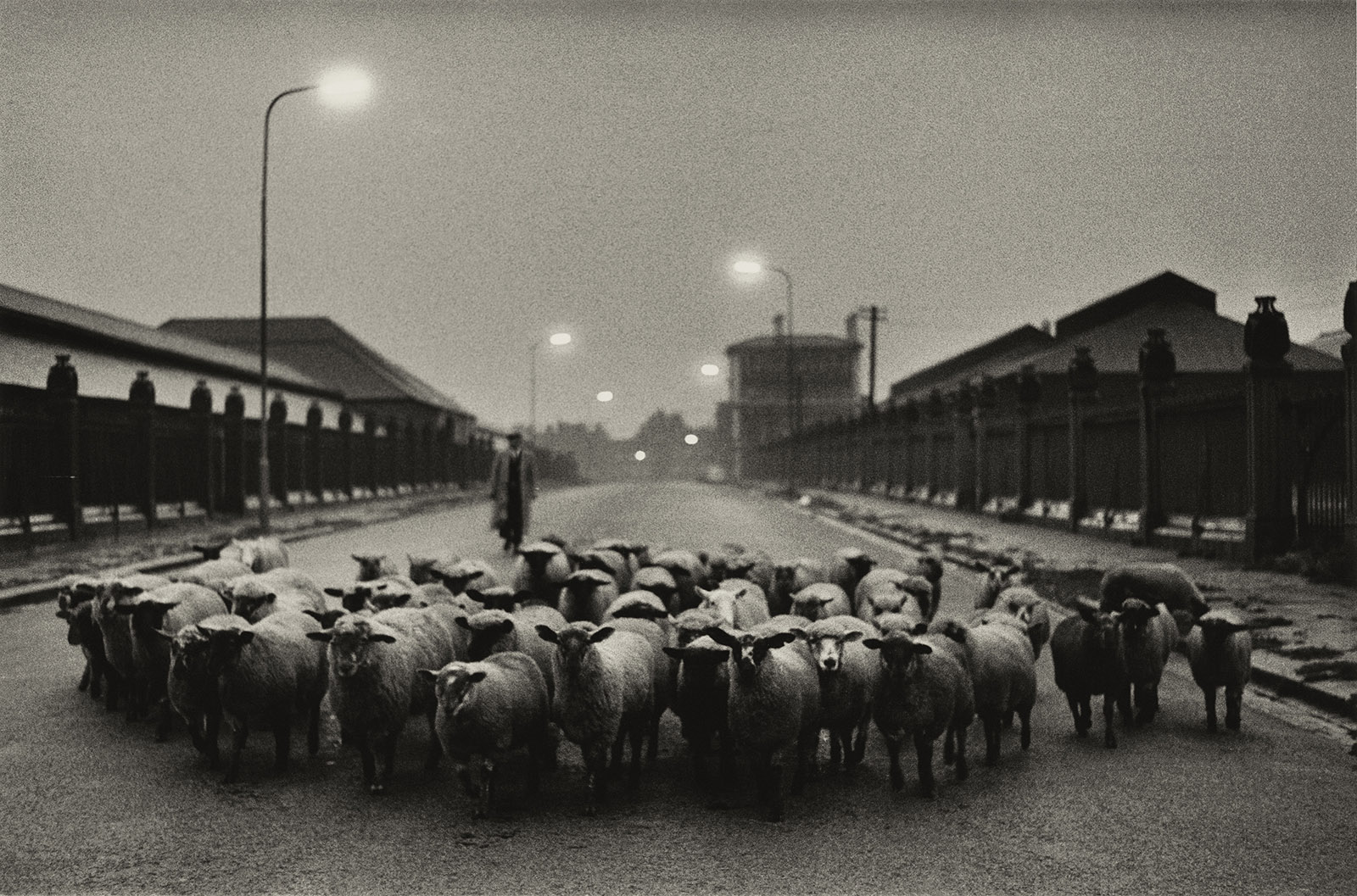

In his early twenties, he began taking photographs of his native Finsbury Park. One of them, The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, showing a gang of lads who might have been modeled on the Jets in the contemporary West Side Story, was published in the Observer in 1958, and launched McCullin’s career. He took many more pictures of a now vanished London—in 1965 sheep were still being driven through the streets to a slaughterhouse in the Caledonian Road, Islington—before he was drawn to flash-points and hotspots: first Berlin, as the Wall was going up, then the bitter conflict in Cyprus in 1964, which McCullin saw from the Turkish side.

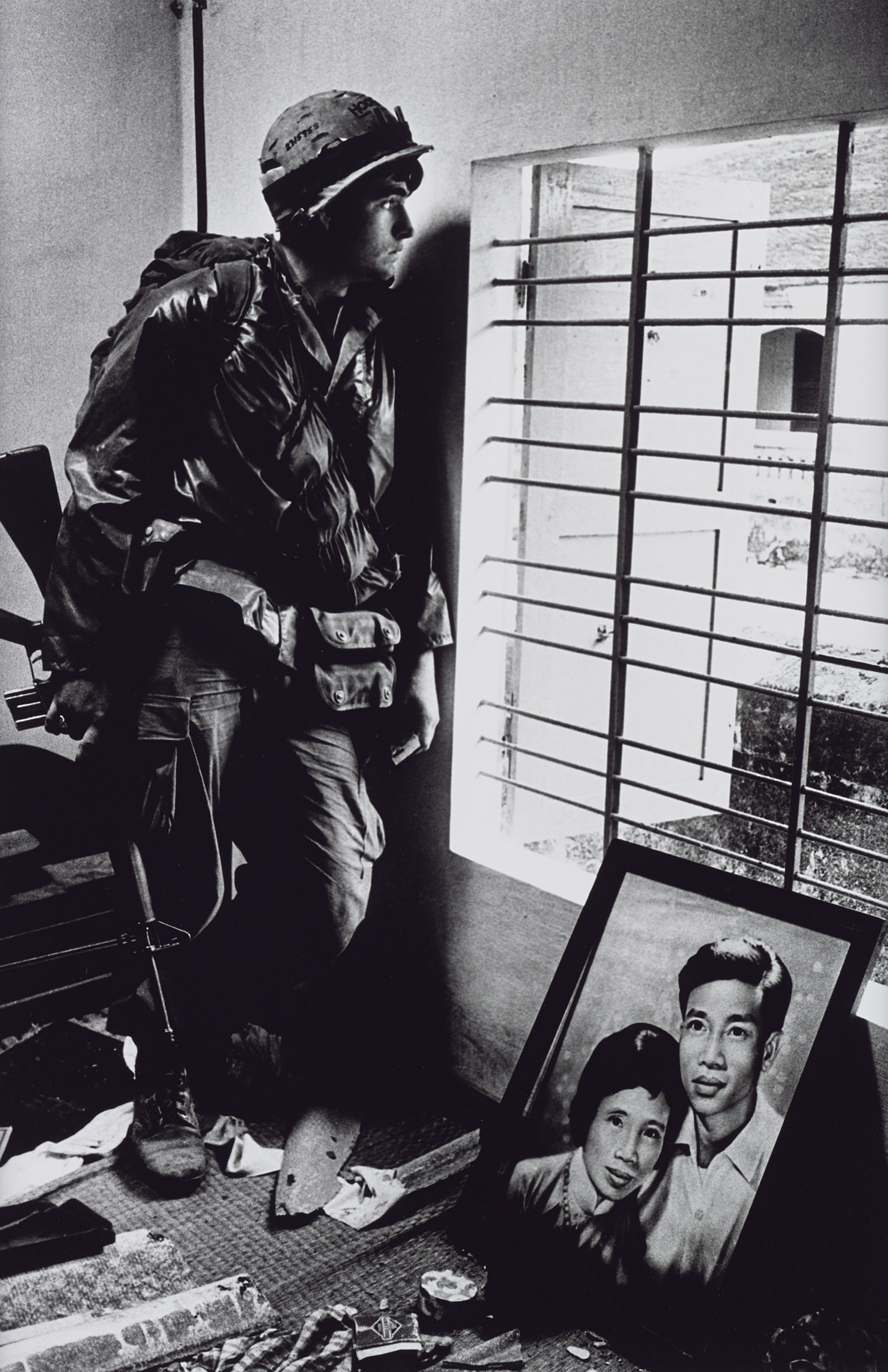

Here, we have his first of so many images of dead bodies, grieving widows and mothers, starving children, and prisoners about to be shot, from wars in Biafra to Cambodia to Beirut to Iraq. McCullin was himself photographed in Cyprus by fellow photojournalist John Bulmer carrying an elderly woman to safety under fire. That wasn’t the last time that McCullin found himself in real danger. He was hit by shrapnel in Cambodia, and one of the more eye-catching exhibits in the Tate show is of the Nikon camera he was carrying in Vietnam in 1970 when—as he only realized afterward—it stopped an AK-47 bullet. Mercifully surviving, McCullin produced images that are now indelibly part of the visual history of the last century, such as a shell-shocked GI at Hue, a dead Vietcong fighter with his possessions, including family snaps, strewn beside him.

There are other dangers than gunfire for the war photographer, almost more than for the war correspondent: the temptations of angry partisanship or aestheticization of horror. McCullin is innocent of the first. “No one was my enemy, by the way,” he says, in the companion book to the show. “There was no enemy in war for me. I was a totally neutral, passing-through person.”

The second hazard might be more problematic. Biafran children with bellies distended by hunger, two dead Khmer Rouge sprawled in almost gymnastic postures, a Bengali father holding the body of his young son who has died of cholera, all come close to being artistic creations like the gyrations of athletes frozen for a split second for the sports pages. Many of McCullin’s pictures first appeared in publications like The Sunday Times of London magazine, where we gazed at these extraordinary images before turning back to breakfast and daily life.

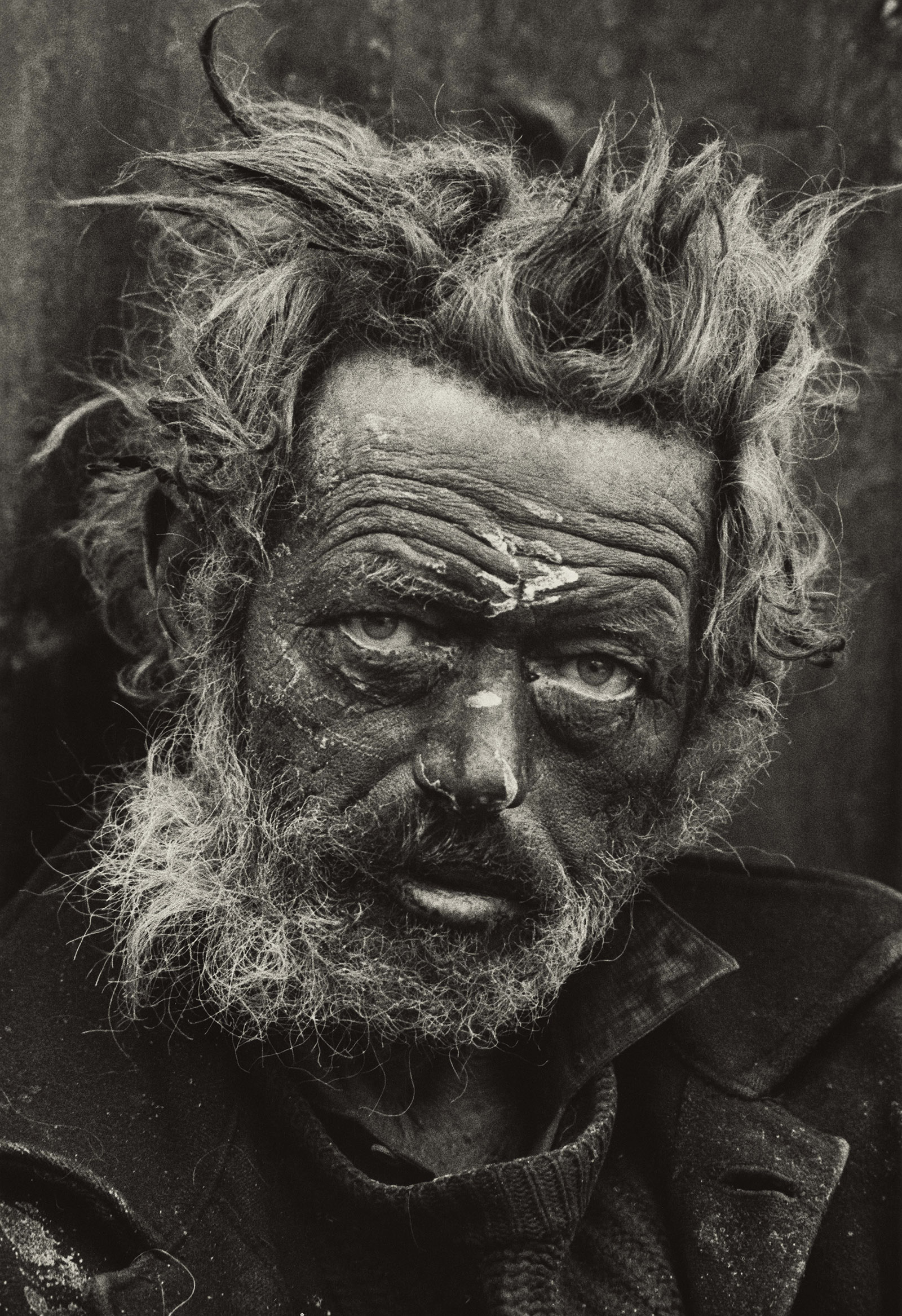

Home in England, McCullin found a different kind of misery. In the 1970s, he photographed the decaying, soon-to-be-post-industrial north of England—the “left-behind” places such as Bradford and Sunderland that would one day vote for Brexit, as much out of despair as hope for a better future. In a photograph like Unemployed Men Gathering Coal, Sunderland (1970), McCullin’s unmistakable affinity with the poor, free of any hint of condescension, gives a more poignant edge to these pictures of destitution in a landscape in which, like the London he photographed fifty years ago, he can find pity amid the misery.

Despite those words, and despite all that he’s witnessed, McCullin in old age has a philosophical, even cheerful mien. His theme in the BBC program is “how extraordinary the English can be—how eccentric,” whether he is picturing the well-to-do picnickers at the Glyndebourne Opera, seaside daytrippers on the pier at Eastbourne (one girl wears a T-shirt that reads “Little Miss Piss-Head”), stallholders in Whitechapel Market in the East End, or fox-hunters in Wiltshire. He likes to think that “for a change I’m photographing people having a day off,” but his taste is for the way that “as a nation we’re really strange people.” But we are also a changed and still changing people: when he returns to Bradford, he comes upon a scene that would have been unlikely there forty years ago—a Shi’ite religious festival.

Advertisement

Looming landscapes of Somerset, the southwest English county he has made his home, fill the last room at the Tate, but these are no fêtes champêtres or pleasing prospects of painted tradition. Some of them may be taken at “the dusk when, like an eyelid’s soundless blink, / The dewfall-hawk comes crossing the shades to alight / Upon the wind-warped upland thorn,” as that Wessex Country poet Thomas Hardy put it. Others seem to have undergone what French movie-makers call la nuit américaine, or day for night, to make them more somber still. “I do tend to turn my landscapes into battlefields,” McCullin says, so that the waterlogged empty fields below Glastonbury Tor might be the devastated Somme. Even his still lifes of plums and mushrooms have a brooding quality.

In the documentary, we see him at home in the dark room that is so important to him. McCullin has always preferred black and white to color photography, and still uses older, mid-format cameras—“once you press the button on a digital camera, it’s done all the work for you”—for their superior clarity. He says mischievously that what he does in the dark room between negative and final print comes close to Photoshopping. But since he spends hours patiently holding up prints to the lamp until he has just the right light, texture, chiaroscuro, it seems more akin to what an artist does when perfecting a woodcut or aquatint—although it’s also a kind of therapy.

The “magic of the dark room,” he says, is where “I hide all my disappointment and grief.”

“Don McCullin” is showing at Tate Britain until May 6.