In a striking 1964 portrait by Antanas Sutkus, a young Lithuanian Pioneer doesn’t smile—despite the fact that it’s September 1, decreed by the Soviet Union’s Central Committee to be the first day of school, a day of celebration. Though the Pioneer is wearing his new uniform and knotted scarf, though schoolchildren are milling around, full of excitement, in a celebratory assembly, this young Pioneer with cropped blond hair is sulking, seemingly wondering what he is doing there, and what there is to celebrate.

“A Pioneer that sulks? This was intolerable at the time,” Sutkus explained. The purpose of the Pioneer divisions, Scout-like in form and Communist in content, was to educate children to be loyal to the ideals of Communism and the party, as expressed by their motto: Pioneer, be ready to fight for the cause of the Communist Party! When the picture was published in the magazine Sovetskoye Foto (Soviet Photo), Sutkus continued, “readers wrote over 200 protest letters, and I was summoned to the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Moscow to give explanations.” He barely escaped a one-way trip to Siberia.

Sutkus’s Planet Lithuania, published last November by Steidl, gathers over 200 images taken between 1959 and 1991, including his famous Pioneer. Sutkus has been celebrated in Lithuania since the 1960s, and is now well recognized in Europe, especially after receiving the prestigious Dr. Erich Salomon Award, a lifetime achievement award for photojournalists, in 2017. But his work is not yet well known in the United States.

Lithuania, a European country bordered by Latvia, Belarus, Poland, and Russia, has a troubled recent history. It was occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940, and (except for the war years when it was taken over by Nazi Germany), remained part of the Soviet Union until August 1991. In an ironic picture entitled Goodbye Party Comrades!, Sutkus captured the moment when, lifted by a crane from its pedestal, Lenin’s statue with its extended arm dangles in the air. On the pedestal, only his bronze boots remain.

During these years of Soviet occupation, the government controlled all aspects of people’s lives, including creative life. In photography and painting, there was propaganda and little else. The Communist Party would not allow the documentation of the many difficult or dark aspects of life: sadness, poverty, the jobless, social outsiders, the disabled, and the old. The representation of topics such as religion, alcoholism, or the pollution of the environment were excluded by so-called “positive censorship.”

“Public spaces, periodicals, exhibitions were under censorship control. It was forbidden to show psychological work and photos that could disturb social order. Pathos and optimism were required,” Sutkus wrote to me in an email in 2007, when I interviewed him with the help of a translator (Sutkus and I didn’t meet in person until my 2017 trip to his studio in Vilnius).

For their attention to everyday life and their tender spirit, the photographs in Planet Lithuania often evoke the spirit of Robert Doisneau, André Kertész, or Paul Strand—but Sutkus only discovered their work and that of other photographers of the humanist school much later in life, when he first traveled outside his country in 1992. Cultural isolation meant there was no access to photography books in Lithuania.

In spite of this seclusion, Sutkus’s work is anything but primitive. The sophistication of this largely self-taught artist is all the more remarkable because it grew primarily from his intuition, grounded in his strong feelings of closeness and empathy for the people and situations he photographed.

Antanas Sutkus was born in 1939, at the start of World War II, in the village of Kluoniškiai on the banks of the Nemunas River. His father, who worked in a peat bog, was a freethinker and leftist. In 1940, when asked by the Soviet occupiers to deliver a speech at the celebrations of the October revolution, Sutkus’s father shot himself in public.

After the Nazis occupied Lithuania in 1941, his mother, guilty by association, had to go into hiding. In 1944, when the Soviets returned, she remained in hiding because of her remarriage to an officer of the Independent Lithuanian Army, an underground organization that worked to regain Lithuania independence. She left the child with his grandparents, who raised him. “They did not talk to me about dad, never told me why my mum couldn’t live with us,” Sutkus explained. “We saw her occasionally, but I missed my dad a lot. Painful thoughts bothered me.”

Sutkus became gravely ill, but the enforced confinement proved to be his deliverance: “The tuberculosis gave me my education because I could read books sixteen hours a day in hospital. My first teachers were writers such as Camus, Kafka, Salinger, García Márquez, Kobo Abe, Dostoevsky, Bulgakov.” Loaned directly by his school teachers who had procured them at great risk, the books had escaped censorship.

Advertisement

Sutkus started taking pictures when he was fifteen or sixteen, mostly capturing friends, family, and the peat bog where he worked over school breaks, earning the money for his first camera. In 1958, he went to university in Vilnius and studied Russian and journalism, then started working for various newspapers, writing articles, and publishing his photographs. He started as a correspondent of a regional newspaper, then wrote and photographed for the newspaper Soviet Student, often filling entire issues of the publication. By 1962, he began shooting for the magazine Literatūra ir menas (Literature and Art), then Tarybinė moteris (Soviet Woman). In 1969, Sutkus was one of the cofounders of the Union of Lithuanian Art Photographers and its chairman until 1990, then from 1996 to 2009. It was the first, and for a long time the only such society within the Soviet Union; it recognized photography as an art form.

Sutkus’s early focus on the world he knew best, that of rural villages, allowed him to pass through the cracks of censorship, because cities were more closely monitored.“In the countryside I could do anything I wanted. My roots are [there],” he told me. “If I had not felt the rustling of the wind in the maple leaves, seen the waves of the wheat fields, listened to the rain beating on the roof of the barn, it would have been hard to become a photographer.”

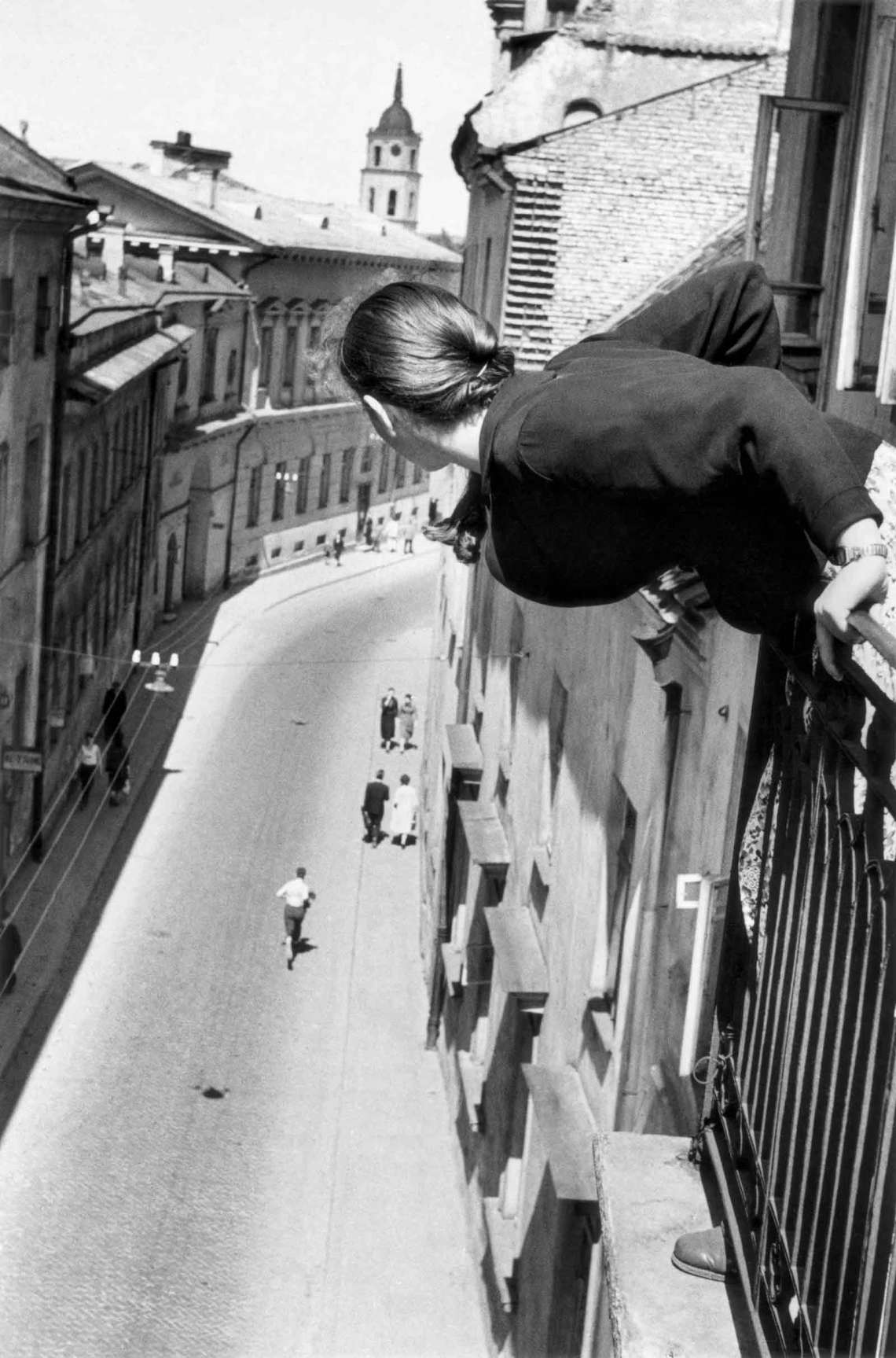

People interest Sutkus foremost. He was never drawn to photojournalism. Even when capturing an event, he often chose to photograph it from the margins. While most photographers covering a marathon would perhaps have made close-ups of the runners and the finish line, Sutkus’s 1959 image is taken instead from the perspective of an onlooker standing in a window high above the race. To take the picture he had to balance over the balcony with friends holding him steady with a belt—he could keep the position long enough for just three exposures. The woman’s hands grip the balcony, her body twists and projects itself into the street, straining to see a solitary runner three stories below. Meanwhile, passers-by continue their stroll on the sunny side of the street, indifferent to the runners beside them.

Preferring to include in his portraits a part of the environment around his subject—public benches, grey patches of snow punctured with puddles, hedges, the perspective of a country road or a field, a faded, cracked wall—Sutkus makes us aware of the often threadbare surroundings of the people he photographs, giving context to his portraiture. Sometimes, the inanimate objects of the environment become subjects themselves, as in this 1959 photograph of a University Dorm in Vilnius: under the harsh ceiling lights, nine umbrellas in two rows rest in front of the doors, their dim shadows projected on the floors and walls, images of parallel solitudes. We don’t see who lives behind the doors.

Of the people he chooses to photograph, it is Sutkus’s familiarity that feeds his intuition. People in his images are almost always aware of the camera, and often face it. Sutkus’s camera is especially drawn to children and teenagers, and he often photographs them in quiet, unguarded moments. Children, he said, “have a life of their own, a world of their own with its own happiness and sadness. It is like a parallel reality. To enter it, you need to go back to being a child.”

Quite literally, the photograph of a little girl at a party is taken at her level: likely fearful of the crowd that looms over her, she takes her mother’s hand and cradles it against her cheek. As big as her face, the hand appears like a large pillow, a reassuring shield. In A School for Blind Children. Chestnuts (1962), one of several pictures Sutkus took at the school, a group of girls are picking up shells from the ground and one girl, her feet in the third position of a ballet dancer, is captured palpating a chestnut, caught in the enjoyment of its shape and rough texture.

In Oranges from Morocco, Vilnius (1975), three boys pose in front of cases of oranges, piled high in columns that seem on the verge of collapsing. The mood is different, quieter and romantic, with a sense of harmony and innocence. A different group of boys appears in First Spring Flowers, Dzukija (1973), still in coats and winter hats, clutching small wild bouquets of tulips, walking along a gravel path in a pine forest. Facing each other in the book, these two images have a similar natural configuration, with the boys arranged in a loose triangle. Though more interested in empathy than geometry, Sutkus nevertheless has a strong eye for composition.

Advertisement

Planet Lithuania presents only a small sample of Sutkus’s vast collection of images of everyday life in Lithuania under Communism from 1956 to 1991. Today, when Sutkus is not working on an exhibition, he is busy filing his 700,000 photographs and negatives, often discovering new images in the process. It is one of the largest existing archives of life under Soviet rule, a record of simple, quiet resistance.

Planet Lithuania by Antanas Sutkus is published by Steidl.