Outside the Ben Uri Gallery, on a leafy North London street aptly named Boundary Road, a sign announces “Art, Identity, Migration,” the triple focus of the gallery. Inside, the works that fill the cool white space speak of turmoil, terror and resilience, a world away from the coffee shops and offices next door. But while the gallery’s history and collection pay tribute to generations of immigrants, its recent decision to sell some of those works, and to adopt a new, broader curatorial policy, have sparked fierce arguments, hard to resolve.

The current exhibition, “Czech Routes”—the fourth in a series, following shows of émigré artists from Germany, Poland, and Austria—contains works by twenty-one painters, printmakers, and sculptors who left Czechoslovakia at different times in the past century. The earliest of these, the lithographer and portraitist Emil Orlík (1870–1932), came to London in 1898. Orlík’s family belonged to the Prague circle that included Kafka and Rilke, and that intense, questioning culture is part of the identity that later artists cherish. One fine bronze by Irena Sedlecká (b. 1928), who stayed in Britain after the USSR crushed the Prague Spring in 1968, is a sculpture of Kafka she made in 1967. “Reading The Trial,” Sedlecká said, “I understood for the first time what it means to be Czech. He made sense of those terrible times when the authorities would simply pull you in for questioning, without your ever knowing the reason. That experience has shaped our national psyche.”

The opening of the show coincided with the eightieth anniversary of Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, six months after Sudetenland was ceded to Germany under the Munich Agreement. Britain became the center of the Czech Resistance, the home of the country’s government-in-exile, and of the Czechoslovak Institute, which exhibited several of the artists shown here. Several found help through the Oskar-Kokoschka-Bund, a group formed by expatriate artists who openly shunned Nazi ideas. Kokoschka (1886–1980) had left Vienna for Prague, where he spoke and wrote on behalf of the Union for Rights and Freedom, joining the Czechoslovak delegation at the Brussels Peace Congress in 1936. Two years later—the year after he gained Czech citizenship— Kokoschka fled to England. His lively Still-Life Studio Exercise (circa 1950) is dedicated to the generous patrons of émigré artists Charles and Regina Aukin, themselves immigrants, from Belarus and from Germany.

Every work here carries a story. The painter and printmaker Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017) and the sculptor Anita Mandl (b. 1926) were among the 669 children who travelled on a Quaker-sponsored Kindertransport train in 1939, leaving their families behind. Both stayed in Britain. While Strenitz lived and worked around London’s Kings Cross Station, her many scenes of railway tracks perhaps harking back to that traumatic journey, Mandl retreated to the Devon countryside and to nature, sculpting simplified and highly polished animal forms, such as her piece on view, Owl (1969).

Other children did not escape. In 1942, Yehuda Bacon (b. 1929) was sent with his family to the ghetto of Terezín (Theresienstadt), and then to Auschwitz, before being liberated in 1945. But while much of his work explores the horrors he experienced, by contrast his ten etchings of a seated figure, Variations on a Theme, are vibrant and colorful. An older artist held in Terezín, Leo Haas, was forced to illustrate propaganda, a task that, ironically, enabled him to draw in secret the scenes he was witnessing. After the war, Haas returned to Terezín to collect around 400 hidden artworks: his Ghetto (1945/1966) was printed from the original plate he’d made in the ghetto.

The exhibition highlights the role of memories in an immigrant’s sense of identity. The recollections can be harsh, reflecting the grimness of ghetto and prison, or affectionate, like the scene in Sabbath in Prague, by Scarlet Nikolska (b. 1949), who came to Britain in 1974. The painter Bedřich Feigl (1885–1965), another of the wave of immigrants in 1939, nostalgic for the continental “Kaffeehaus” culture, returned constantly to the theme of coffee-houses and restaurants, “the market places of life,” as he called them Trying to recapture this atmosphere, Feigl and others met at Cosmo, West Hampstead, where, he said, one could spend all day reading “over a single cup of coffee or consuming Schnitzel and Strudel with fellow refugees.”

*

By December 1939, as the curator, Nicola Baird, explains in her notes to the exhibition, about 12,000 refugees from Czechoslovakia had arrived. Two thirds of those who registered with the Czech Refugee Trust Fund were Jewish. Most of the works in this show belong to the Ben Uri’s own collection, pointing to the gallery’s original mission to support Jewish immigrant artists. The Ben Uri Art Society was founded in 1915 as an art society in Whitechapel, in London’s East End, by a Lithuanian-born artist Lazar Berson, taking its name from Bezalel Ben Uri, the biblical creator of the tabernacle in the Temple in Jerusalem, and creating a link to the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem. Ten years later, the society opened a gallery in Bloomsbury, and went on to move between various homes around London until it settled in 1964 at 21 Dean Street in Soho, on the fourth floor of the newly built West End Great Synagogue.

Advertisement

Over time, the Ben Uri Foundation built up a remarkable collection comprising some 1,300 works from thirty-five countries, in thirty different mediums, by 380 artists—including many famous names such as David Bomberg, Frank Auerbach, Marc Chagall, Jacob Epstein, Chaim Soutine, Mark Gertler, George Grosz, Leon Kossoff, R.B. Kitaj, Max Lieberman, and Alfred Wolmark. But in 1995 the Dean Street synagogue was sold, and for six years the gallery had no home, until the Boundary Road house was rented in 2002. This was seen as a short-term solution, but a plan to find a larger space in central London was then blocked by rising property prices.

By 2015, when its centenary exhibition “Out of Chaos” showed in the Inigo Rooms in Somerset House in the Strand, the museum had decided on a change in direction. A survey showed that the collection was not, as had been assumed, solely by Anglo-Jewish artists; instead, it contained works by artists from a diverse range of nationalities and backgrounds, including a relatively high proportion of women. This prompted the foundation to move to a new collecting policy focused on immigrant artists generally. With that came a decision to establish the Ben Uri Research Unit for the Study of the Immigrant Contribution to British Visual Arts since 1900 (BURU), which would create a comprehensive digital dictionary related to art and immigration, including a database of artists, teachers, scholars, critics, patrons, dealers, and gallerists. In addition, the foundation decided to use the gallery’s existing work with art and memory for therapeutic purposes through the Ben Uri Arts and Dementia Unit—like music and poetry, visual art often prompts long-forgotten memories.

The trustees of the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum accepted the new approach. What they did not accept was the startling decision to fund this ambitious program by selling, over time, up to 700 works, over half the collection. When Sotheby’s autumn 2018 catalogue advertised the first Ben Uri sale on its front cover, there was outrage: among the twenty-four works listed were five Bombergs, including the famous At the Window (1919), as well as Mark Gertler’s Nude (1938).

On the day of the sale, November 20, eleven members of Ben Uri’s International Advisory Committee resigned en masse, including Sir Nicholas Serota, a former director of the Tate and the Chair of Arts Council England, a major public grant-giver. In their open letter, they wrote: “We were not consulted in advance on the proposed sales and believe that sales of such important works from the collection are a grave mistake. We believe that these sales will undermine the ability of the trustees to secure future gifts and a future home for the collection.” The Museums Association, Britain’s leading membership body for gallery and museum professionals, had already advised that such a sale would breach the ruling in its code of ethics that “financially motivated disposal risks damaging public confidence in museums and should only be undertaken in exceptional circumstances.”

De-accessioning—shedding works of art, books, archives that are no longer seen as central to a museum’s role, or are rarely seen, and becoming too expensive to store—is always a thorny issue. Some works are “tethered” by the terms of wills or grants, while others have specific conditions for sale. But the central issues are the subjective sense of what makes up the distinctive core of a collection, and how this relates to the mission of an organization. That was the rub here. While the advisory board felt that the works being sold formed “the very heart of the Ben Uri collection,” the museum’s management disagreed, arguing that their guiding principles should be sustainability and the widening of collection policies to all immigrant communities.

But is it right to shed so much of a historic collection? Will the aim of embracing all immigrant communities dilute the gallery’s essential character? There is certainly a great need for refugees to have access to art spaces, as there was for the Jewish artists who fled here in the late 1930s. So far, the initiatives have been good, but few. This spring, The House of Illustration, a public art gallery established in the Kings Cross area of London in 2014, mounted “Journeys Drawn: Illustration from the Refugee Crisis,” a show comprising forty multimedia works by twelve contemporary artists. And in “Am I My Brother’s Keeper?,” a touring exhibit sponsored by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the British-born artist Kate Daudy transformed a tent from the Za’atari camp in Jordan into an installation that will be installed in St. Paul’s Cathedral in early June, with an accompanying festival.

Advertisement

All exhibitions that focus on immigration tend to alight on ideas of “home,” the lost place, the temporary tent, the found safe place. Beyond all the arguments about collecting and display, immigrant artists will continue to illuminate buried memories and express the complex desires for community and home.

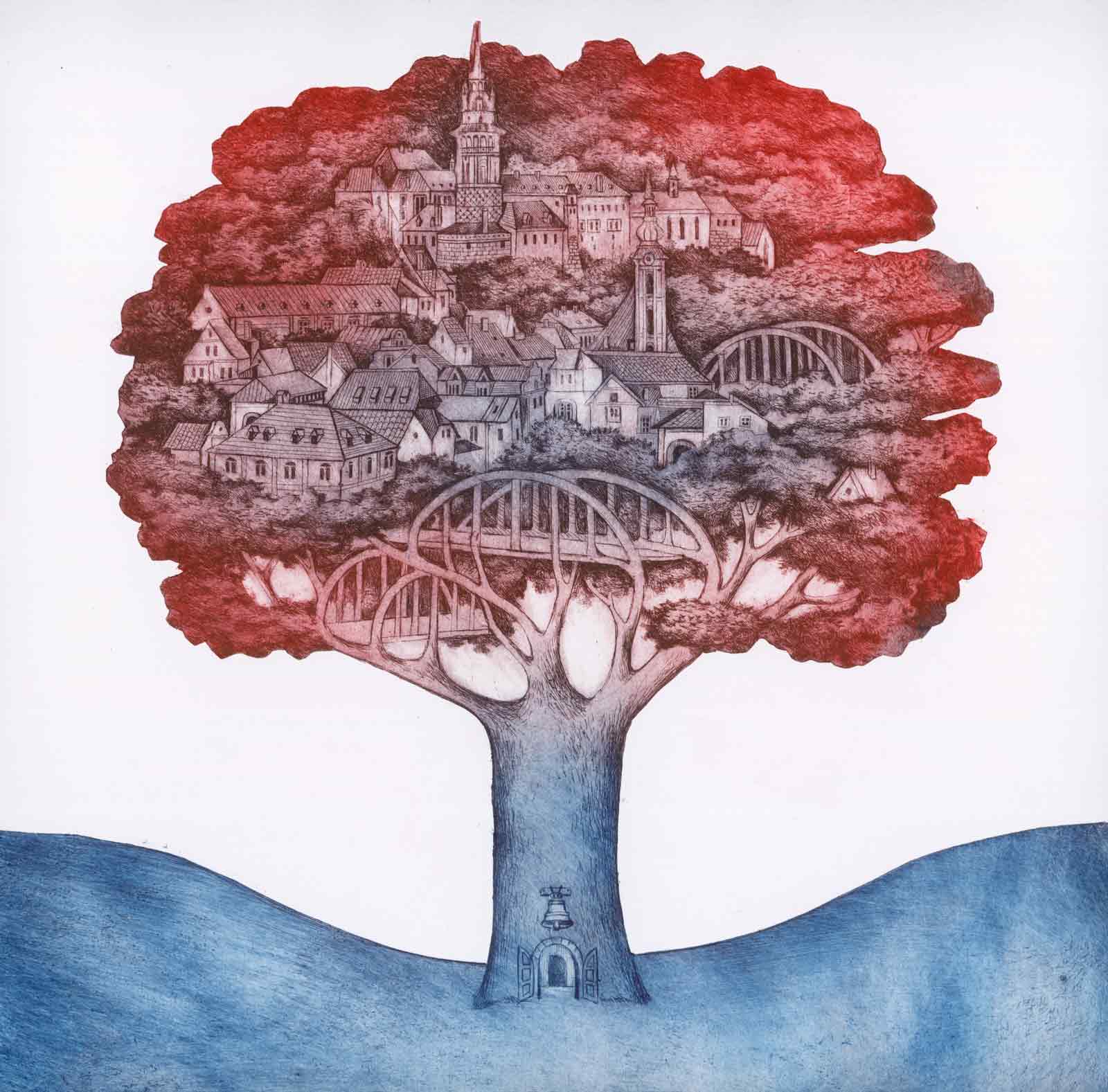

Mila Fürstová, born in 1975, came to London to study at the Royal College of Art. Her residence is chosen, not forced, yet her etchings, included in “Czech Routes,” hauntingly evoke the themes of flight, settlement, and investment in the future. Town Tree (2014) has the feel of an exile looking back at roots in another land, while Nest (2011) shows an egg in its nest balanced at an angle, with tiny London scenes woven into the twigs and branches. Explaining her technique, Fürstová writes: “I draw with a needle onto a plate, allowing the image to quietly grow, whilst a fragile silver line emerges from a dark background as if a distant memory was traced from the unconscious.”

“Czech Routes: Selected Czechoslovak Artists in Britain” is at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, St. John’s Wood, London, through May 20.