When I was living in Kingston, Jamaica, a few years ago, the caretaker of our building died. For the purposes of this essay, I’m going to call him Mr. A. Mr. A was a helpful older man who was always willing to help fix whatever was broken. In fact, again for the purposes of this essay, the word fix isn’t quite right. He’d resurrect them, bring them back to life. You never knew which things he’d be able to resurrect, though, until he was halfway through—when it became clear his powers would either prevail or had failed him. Though a fluorescent light proved to permanently flicker, whenever Mr. A played around with the stove it worked, even after I’d spent hours with no luck.

One weekend, Mr. A was supposed to be away, but sadly, he didn’t end up going anywhere. The effects of the tropical climate eventually made his death obvious. After Mr. A’s body was removed by police, the death registered, and everyone informed, his possessions were brought into the yard to be left out overnight, the mattress turned over, then furniture returned and rearranged. When I was describing this to Kei Miller, author of the novel Augustown and a friend of mine, he assured me that Mr. A’s bedroom would have had to be swept immediately as well, the idea being that the duppy (the Jamaican word for ghost) would also need sweeping out. The furniture rearrangement? That was so that Mr. A wouldn’t be able to recognize the room if he returned. All of this was to be done in order to stop Mr. A’s duppy from being resurrected in the room in which he’d spent his life.

I was interested in the way these death rituals revealed a conception of a more active relationship between the living and the dead than I was familiar with, having grown up in Canada. In his book The Dominion of the Dead (2003), Robert Pogue Harrison thinks about the ways that the dead are with us. “If humans dwell, the dead, as it were, indwell,” he writes. For Harrison, burying the dead gives us a place to stand—we stand on those who came before. But, according to Miller, an old Jamaican saying suggests that it’s more than the past influencing the present: “Respect the dead, because it is by their leave that we walk.” The dead need no permission. Instead, we rely on their leave-taking. As the Jamaican novelist Marlon James has said: “Duppies don’t need you to believe in them to exist.”

This assertion of the dead into the sphere of the living is evident throughout the island, but there’s a particular element of Jamaican culture that demonstrates it most powerfully, and that is the foundation of Jamaican music: the soundsystem.

*

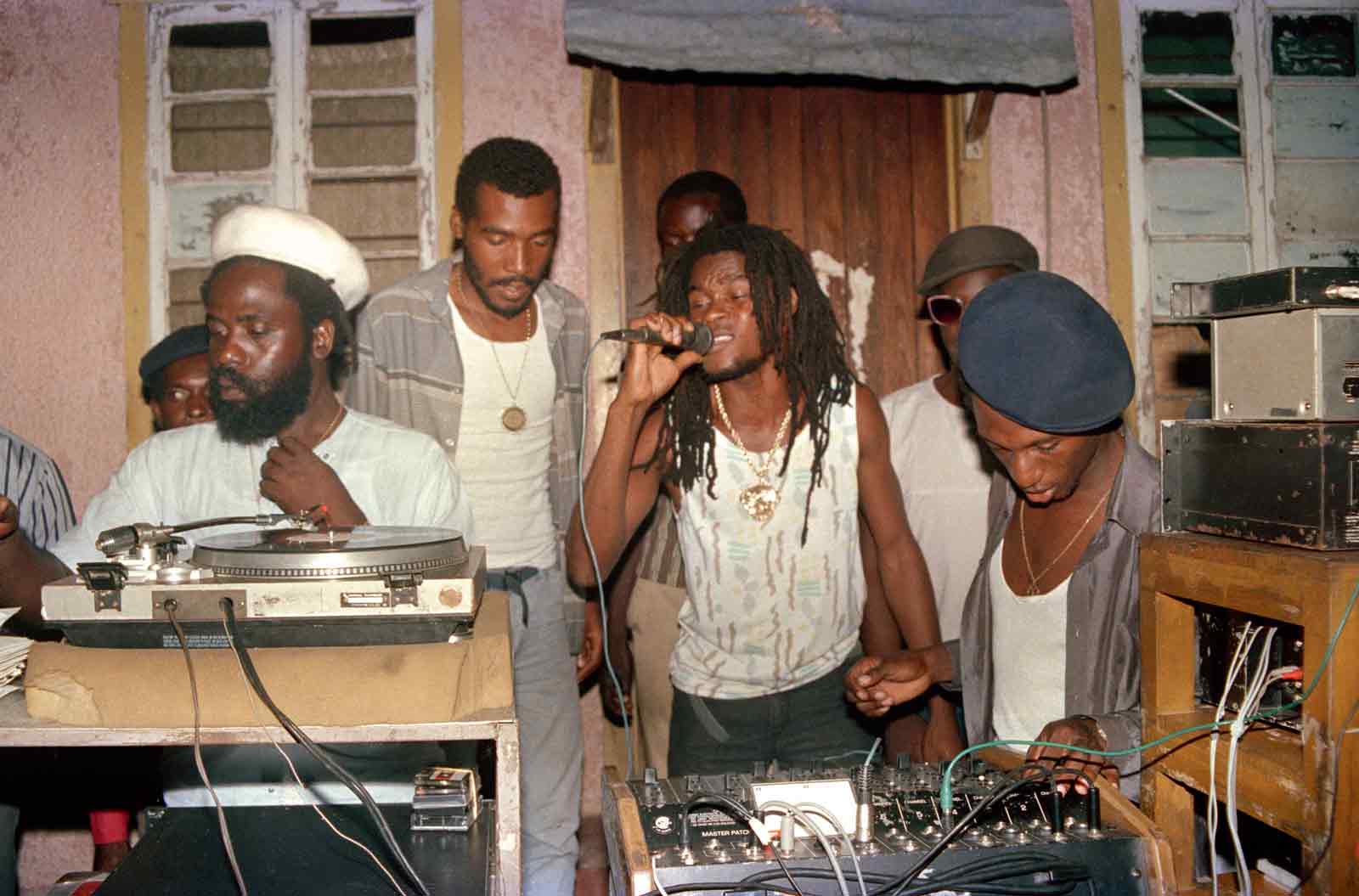

Writing about music for the last two decades, I’ve spent quite a bit of time talking about how the soundsystem is the basis upon which Jamaican music has developed (and I’ve argued that it’s the best way to listen to music, period). It’s the dissemination of music on mobile discotheques: stacks of (preferably) custom-built speakers that can be loaded onto a truck and strung up anywhere to create a dancehall session. In the beginning, soundsystems played American R&B and calypso, just with the bass amped up as high as possible. From the 1950s to today, the sound from these systems has created the dancehall space, as well as the genre of music and influential culture of the same name.

These after-midnight parties showcase an array of fashion in a setting where one can watch or learn a constantly growing assortment of dances and listen to lectures from whoever holds the mic (there’s a reason why legendary soundsystem Stone Love calls their weekly Wednesday-night session “dancehall university”). These dances are actually rooted in the funeral traditions of Jamaican society. Professor Clinton Hutton, a scholar of Jamaican folk religion, has discussed how certain death and burial practices of Afro-Christian religious movements such as Revival Zion are reflected in soundsystem culture: “It’s the same method,” he told me, “the old helped to shape the modern. The evolution of the soundsystem, the Revival wake tradition and the movements in them, the manner of oral expression in them, the poetry traditions, the chanting traditions, were taken into the dancehall. Taken into the making of dubplates and so on.”

The “setup” or “nine night,” which takes place for nine days after a death, culminating the night before the burial, is a kind of wake. Storytelling, singing, and dancing celebrate and memorialize the dead. The “Dinki Mini” is the characteristic dance of the nine night, full of gestural references to sex and fertility—birth being the opposite of death. If holding a wake is a custom that combines grief with celebration, life with death, so, too, is the dancehall, which itself challenges physical and metaphorical borders and boundaries. The open, circular area begins with people lining the edges but gradually fills as the night goes on, and holds songs that speak of love, hate, death, life, party, revolution, and more.

Advertisement

The most pointed discussions of death in dancehall are found in the soundclash, a musical competition between rival soundsystems working to prove which has the most powerful musical and verbal weaponry. Stacks of speakers, cutting insults, and specially recorded songs act as ammunition against a rival. The metaphors for death are constant: references to burial, soundclash after soundclash entitled “Sound fi Dead,” “Death before Dishonour,” “Final Battle/Conflict/Clash,” and so on. Rival soundsystems fight to the death in a soundclash, and the goal is always to “kill” the opposing sound.

In the 1970s, soundsystems would clash using vocalists performing over instrumental rhythms on soundsystems built from the ground up, using an ingenious hodgepodge of materials put together by arguably some of the most innovative sound engineers in musical history. At that time, soundclash meant that soundsystems would quite literally be killed—their speakers blown, amps shot, vocalists unable to continue. As clash has developed, performances have become less important and pre-recorded music has increasingly dominated, from 45s to CDs to other portable and digital formats. But the emphasis has always been on having music that can score a fatal blow, and it is the crowd that decides who’s left standing.

Today, rival sounds will use the same system when they compete, but they bring their musical libraries and the ever important “dub box,” full of a soundsystem’s prized “dubplates.” Because, although soundsystems can get a crowd on their side by “juggling”—that is, playing singles—the dubplate is the most important tool in a clash. It is also on a dubplate that we move beyond discourse and metaphor, toward actual traces of the past, voices from beyond the grave.

*

A dubplate is a special, personalized recording of a usually pre-existing track that acts as a kind of praise song. In the case of a soundclash, a dubplate creatively hails one soundsystem over the other. The best dubplates take something that is well known—popular lyrics—and create unexpected phrasing, generally celebrating the glory of the plate’s owner. For example, for Bass Odyssey sound, John Holt added the following insult to the lyrics of his love song “Pick Up the Pieces”: “Pick up the pieces of your sound and throw them away!” Listeners learn to pay attention for the best bits of wordplay and invention. In a clash, soundsystems need these dubplates if they have any hope of winning, and will thus commission versions of the latest and greatest artists, recorded with a specific person, place, event, or rival in mind. Soundsystems that have been around for a while will have a collection of dubplates, ready for use at opportune times.

When soundsystems compete, there are a number of pre-defined rounds; some are subject-based (weed songs, love songs, rude boy or “outlaw” songs), some require dubplates. The final round is always a “dub-fi-dub” where soundsystems go back and forth playing dubplates, the crowd making their preferences clear through applause, enthusiasm, and sometimes the clang of large metal pot covers or burst of flame from the combination of a lighter and aerosol can. The most coveted artillery of all? The “dead artist dub.”

Garfield “Chin” Bourne, promoter for the last three decades of the Irish and Chin World Clash and Rumble series of international sound clash events, emphasized the significance of a dubplate from an artist who’s no longer living when he told me, “A part of sound clash competitiveness surrounds who can play certain tunes from certain artists, especially veterans, so, of course, with the passing of some of these artistes, the value of their dubs skyrockets for the sounds who were able to acquire them.” A “dead man” round, in which a soundsystem can only play dubplates by what Fyah C of Brooklyn-based LP International soundsystem refer to as “fallen soldiers,” allows a soundsystem to display the wealth and depth of its dub catalogue. This can mean playing a legendary artist such as rocksteady pioneer Prince Buster, but from my experience (and from YouTube views), it’s clear that artists who died in their prime, such as Garnett Silk and Dennis Brown, are particularly significant. And these classic songs never get old. As Chin says, “What is certain is that foundation sounds will never retire their classic dubs, especially those from artists who have passed. In fact, many have become anthems for these respective sounds.”

Advertisement

LP International is known for having the largest collection of Dennis Brown dubplates in the world. As Fyah C told me, “Dennis Brown is an artist who was loved by the fans. His music was very spiritual and touched the fans in different ways… Amazing. How people would just stand in awe to see how many [Dennis Brown dubplates] we could play back to back to back.”

The only way to maintain the evolution of the soundclash is for newer generations to enter the fray, and if a soundsystem is judged on a dead artist collection, this could, as Bourne noted, risk losing some “potentially brilliant young competitors” for whom recording the dead is an impossibility. Promoters like Irish and Chin have to figure out strategies to deal with the dead. The furniture needs to be moved around.

The voices of the dead remind listeners of what has come before, establishing a historical record within the competition and underlining the constant relevance of the roots of the music, what is referred to as “foundation.” Fyah C is clear: “You can’t build anything without a sturdy foundation… You must know your past to move forward.” When the latest voices are as valuable as those long dead, it impresses upon the listening audience that the past is always present, and retaining history is key to moving forward.

Dubplates themselves communicate not only a relationship with the past, but also a particular relationship between an artist and moment in time and the dubplate’s owner. The reason a soundsystem like LP International has a collection of forty to fifty Dennis Brown dubplates is partly because the sound has been around since 1982, but, more importantly, Puma, one of the founders of the sound, was good friends with Dennis Brown. As Fyah C reports, “They were in the studio for a very long time, and this made the assortment grow very big.”

But over the last quarter century, what might be referred to as “cookie cutter” dubplates have become readily available on the Internet. For $500 sent through PayPal, you can get an MP3 that uses your soundsystem name, but sounds the same as the clip anyone who’s sent $500 through PayPal receives. A dubplate historically stemmed from relationships, built over time and imbued with real connection. Dubplates also once required and reflected a temporal specificity: they were usually recorded in one take, the singer holding a quickly scribbled note about people, events, details and improvising the custom addition into the song. There’s something lost in this transactional, disembodied version of the dubplate. One has to wonder if it carries the same weight now, and into the future of dancehall.

*

Though I’ve been writing about Jamaican music for almost two decades, lived in Jamaica for four years, and can’t seem to stay away for more than six months at a time, it’s difficult for me to write about my own relationship to dancehall. I know that the culture isn’t mine to own: I’m a white, Irish-Scottish descendent of settlers from Oshawa, Ontario. Outsiders like me can attend dances. We can follow soundsystems. We can commission a dubplate. But I am aware that my relationship to the culture is different from someone who came from within it. The dubplate process itself extends outwards, as an invitation for collaboration and revision, while still maintaining and reminding the listener of essential boundaries.

I once ordered a dubplate for a wedding of some friends in Montreal. A range of relationships allowed for a connection to be made with a singer named Nana McLean (known as “Canada’s reggae diva”). Her song “Nana’s Medley,” in which she plaintively sings “please say you’ll be mine,” was perfect for a wedding. The name of the bride and groom were provided, and the artist improvised. Though my partner at the time and I couldn’t attend the wedding, the dubplate stood in for us, to make our presence felt.

Dubplates were originally acetate pressings of music that could only be played a limited number of times before they, too, passed away—unable to carry the music they held any further. The advent of digital music meant this ephemerality is no longer a concern. But even though music can now be contained in the cloud, the dubplate still represents this ability to capture a moment in time. If a dub becomes particularly well-known (sometimes enough to be released as its own song), it’s nearly impossible to hear the original without hearing the later dub. For instance, I can’t hear the sweet strains of crooner Sanchez singing “Praise Him,” with its chorus “Oh Jah I love you so,” without hearing the substituted lyrics “Stone Love I love you so.” The original song, therefore, carries the trace of the dub. It carries the later history.

I also own a dubplate that carries significant weight, from my own past. It was a gift, given to me by someone who I thought I’d spend the rest of my life with, but then didn’t. It’s a dub of “That’s Life” by an artist named Baijie. I can’t listen to it without being reminded of the relationship I couldn’t make work. I want to move the furniture around, don’t want to allow the feelings to find their way back, but Baijie’s voice reminds me that the past does have an impact on the present.

Duppies may not need us to believe in them in order to exist, as Marlon James says. But perhaps we need them to remind us that we do. Dancehall and its practices conjure ghosts, the past, history. The circle that begins any dancehall event, with people standing furtively along the perimeter of the venue, sipping Red Stripe and rum, waits to be filled over the course of the night. In this space we engage with history, filled with the past, to recognize that we dwell in it and it in us. The dubplate is a visceral example of this, suggesting the resonance of the past on the present, the repercussions of colonialism as ongoing oppression and inequality—a subject that expresses itself unapologetically in both the format and lyrical content of dancehall music.

The dead still come back, frequently, and the dancehall is careful not to rearrange the furniture. In Kei Miller’s Augustown, the duppy narrator puts it this way: “Here is the truth: each day contains much more than its own hours, or minutes, or seconds. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say that every day contains all of history.” Each time it is played, a dubplate is a reminder that the past exists within the present.