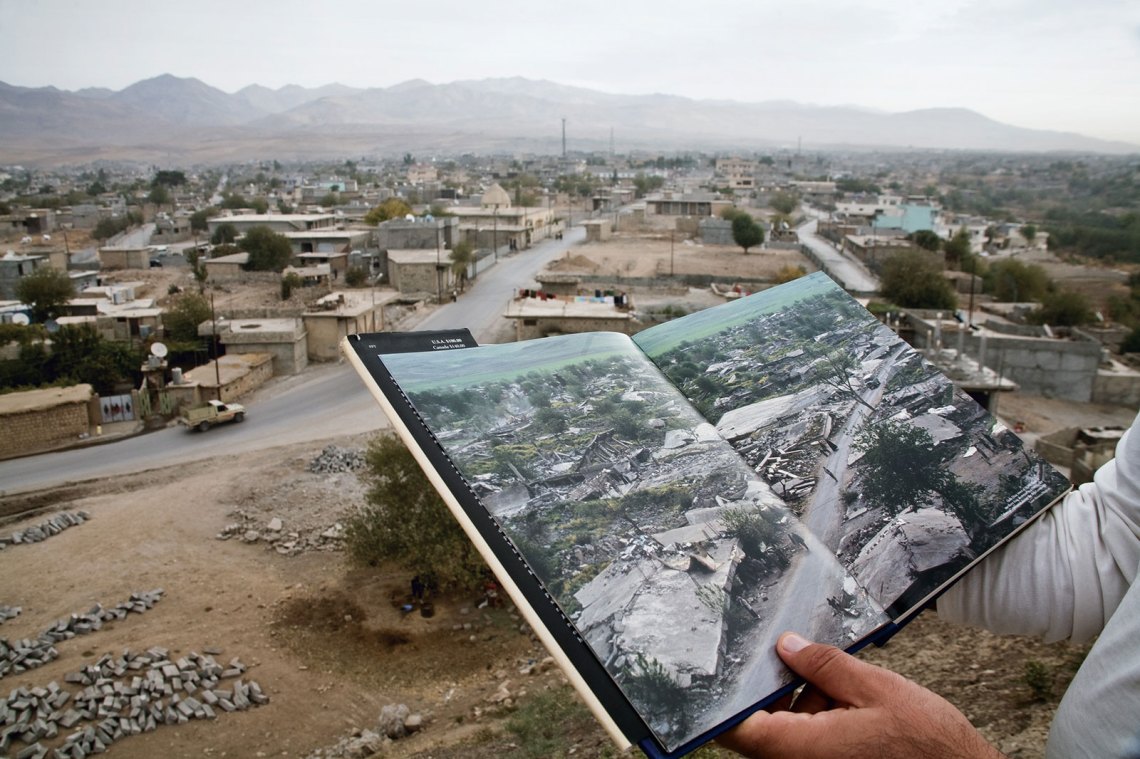

One of Susan Meiselas’s most disturbing images, Cuesta del Plomo, shows a man’s body, half eaten by vultures, lying in the hills above Managua, near a lake. The photographer stumbled across the grisly scene soon after she arrived in Nicaragua—she had happened upon a place where Somoza’s death squads dumped their victims. In 2004, the picture was placed in a frame in the very spot. By then the bodies were all long buried; the landscape gave no clue to its past until the evidence contained in the picture returned.

That innocent green landscape made me think about Rwanda. Those of us who have experienced war—survivors, soldiers, reporters, aid workers—are haunted by what we cannot unsee. The images recur in nightmares, or distort a vista that hides a personal horror. I wince every time a new visitor extols the beauty of the hills of Rwanda—those of us who witnessed the 1994 genocide do not see neat fields and forests, but ditches of bodies with their throats cut and piles of skulls hidden in the folds of the hills. We lurch between wanting to spare others and a desperate need for them also to see the pictures in our heads. It’s not just that we can’t get rid of the ghosts, but that the pastoral scene boosts government propaganda that Rwandans live in harmony now and no longer fear the neighbors who killed their parents and grandparents. Whatever they say, we know how the past speaks—or shouts—to the present.

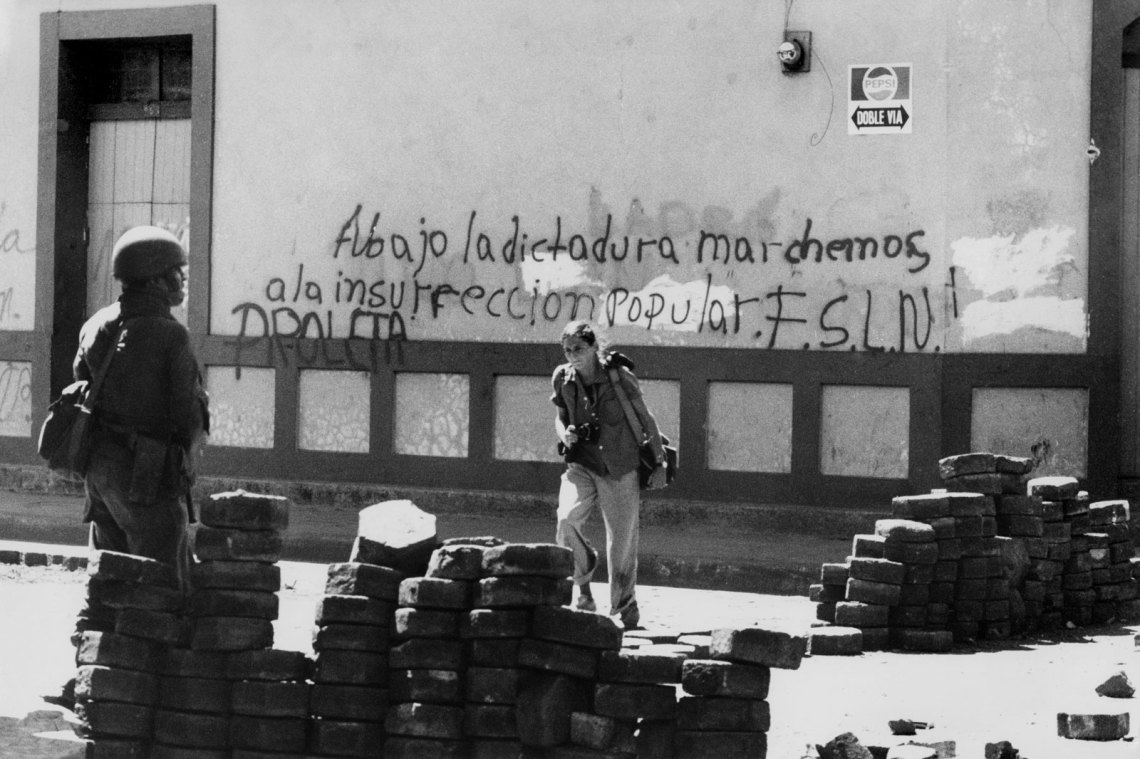

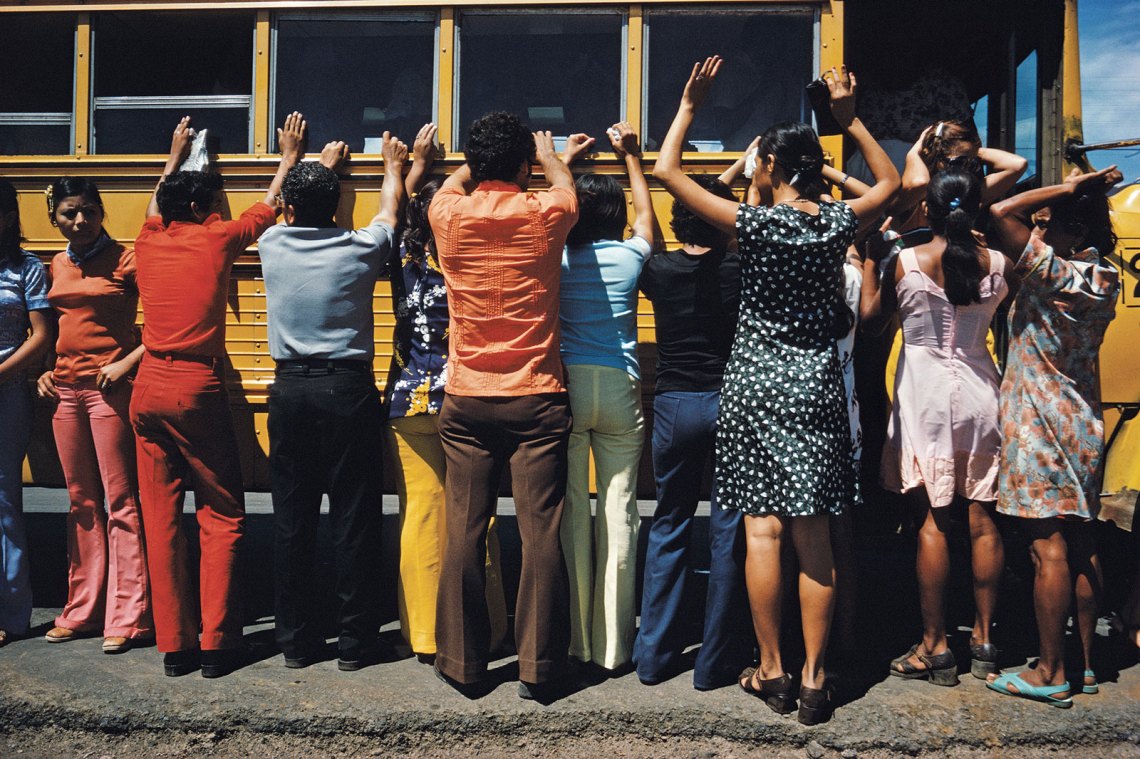

Meiselas’s are some of the best-known photographs from the conflicts in Central America. She arrived in Nicaragua in 1978 when the country was on the cusp of revolution, and stayed in the region on and off for the next twenty-five years.

In Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline (2017), she attempts to unpack her relationship with her subjects, and examine how photographs change meaning over time, while Susan Meiselas: Mediations (2018) features essays about her work by curators and visual theorists. A political ingenue, it took Meiselas some time to understand the role the US government played in keeping the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza in power, and she agonized about her role as an American as well as a photographer. She felt conflicted about “on the one hand, having to work like a professional photojournalist, and, on the other, wanting my photographs to be of some use to the Nicaraguans and their struggle.”

One of her most famous images, Molotov Man, shows a revolutionary, looking like Ché with a beret on his dark curls, all tension and pent-up motion, as he leans back to lob a flaming Molotov cocktail. The details are exquisite: the petrol-filled Pepsi bottle, the crucifix swinging round his neck, the bandage round his other hand gripping a rifle, his comrades looking on from the shelter of sandbags. It ended up on the cover of a Nicaraguan church publication and even on a box of matches. It was also used as a recruiting poster for the Sandinistas, the revolutionary movement that overthrew Somoza, and, after taking power, raised a militia to combat US-backed “contras” who were trying to reverse the revolution.

Over time, Meiselas was gratified to note that many Nicaraguans came to value her photographs as “souvenirs or landmarks,” but she realized that the significance of an image may shift with time, so ten years later, she returned to find the man who had become famous because of her picture. Pablo “Bareta” Arauz was living in the north of Nicaragua, and had worked a number of jobs since the revolution. “In his mind he was still a Sandinista,” she writes. “I think he is proud to be a symbol of the revolution.” Many other Nicaraguans, however, were disillusioned by their continued poverty and the increasingly authoritarian tendencies of the Sandinista government. In an earlier book, Meiselas is quoted as saying that Americans “lost the luxury of a dream, but for the Nicaraguans it was much much worse.”

Advertisement

In 2004, Meiselas returned to Nicaragua again with nineteen of her pictures printed on huge gauzy drapes to hang in or near the places where she had shot them, an exhibition called “Reframing History.” A short film was made of the installation, in which Nicaraguans reflected on the hardship of those days, and the lack of improvement in their lives. Meiselas wanted to explore collective memory. “The witness has always to protect memory from erasure.” But not all young Nicaraguans welcomed the history lesson—in pictures of the hangings we see some looking on in curiosity but others walk past, unconcerned. They had no interest in resurrecting their parents’ memories for hope. Their generation knew too much about disappointment and disillusion.

Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline (2017) is published by Aperture. Susan Meiselas: Mediations (2018) is published by Damiani.