In the 1979 novel Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick, who was my mother, the narrator recalls her youth as a jazz enthusiast in the late 1940s, including a visit to Harlem to see Billie Holiday. Toward the end of the chapter in which that occurs, the narrator, herself named Elizabeth, says:

Goodbye? I have left out my abortion, left out running from the pale, frightened doctors and their sallow, furious wives in the grimy, curtained offices on West End Avenue…

I ended up with a cheerful, never-lost-a-case black practitioner, who smoked a cigar throughout. When it was over, he handed me his card. It was an advertisement for the funeral home he also operated. Can you believe it, darling? he said.

What’s striking is that the abortion is mentioned as if it were an afterthought, a casual-seeming, almost thrown-away memory. My mother wrote this work of experimental fiction some time after her divorce from my father, during the period of what came to be called the second wave of feminism. As I later learned, my mother had had two abortions at that time in her life.

When my mother was in her seventies and I was in my early thirties, I had my own unwanted pregnancy. I scheduled an abortion, but before the procedure could be performed, I became seriously ill, requiring emergency surgery: the pregnancy turned out to be ectopic. My mother accompanied me to the hospital and spoke to the surgeon. As I subsequently discovered, she had done as much bullying as waiting. “I made him operate,” she told me. “I told him you would die.” I believe she saved my life.

Recently, I came across this piece my mother wrote for The Morning Call, which will be republished in the forthcoming The Uncollected Elizabeth Hardwick (edited by Alex Andriesse). Composed in August 1996, when the Republican National Convention was debating an anti-abortion plank—though a measure less extreme than those recently passed by Republican-controlled statehouses in Georgia and Alabama and designed to test the Supreme Court’s commitment to Roe v. Wade—her opinion piece might also be casual-seeming, almost thrown-away, in its satirical jabs at men who seek to control women’s bodies. But knowing she must have had in mind her experience and mine, and no doubt that of female friends, I realized just how serious Elizabeth Hardwick was about it.

—Harriet Lowell

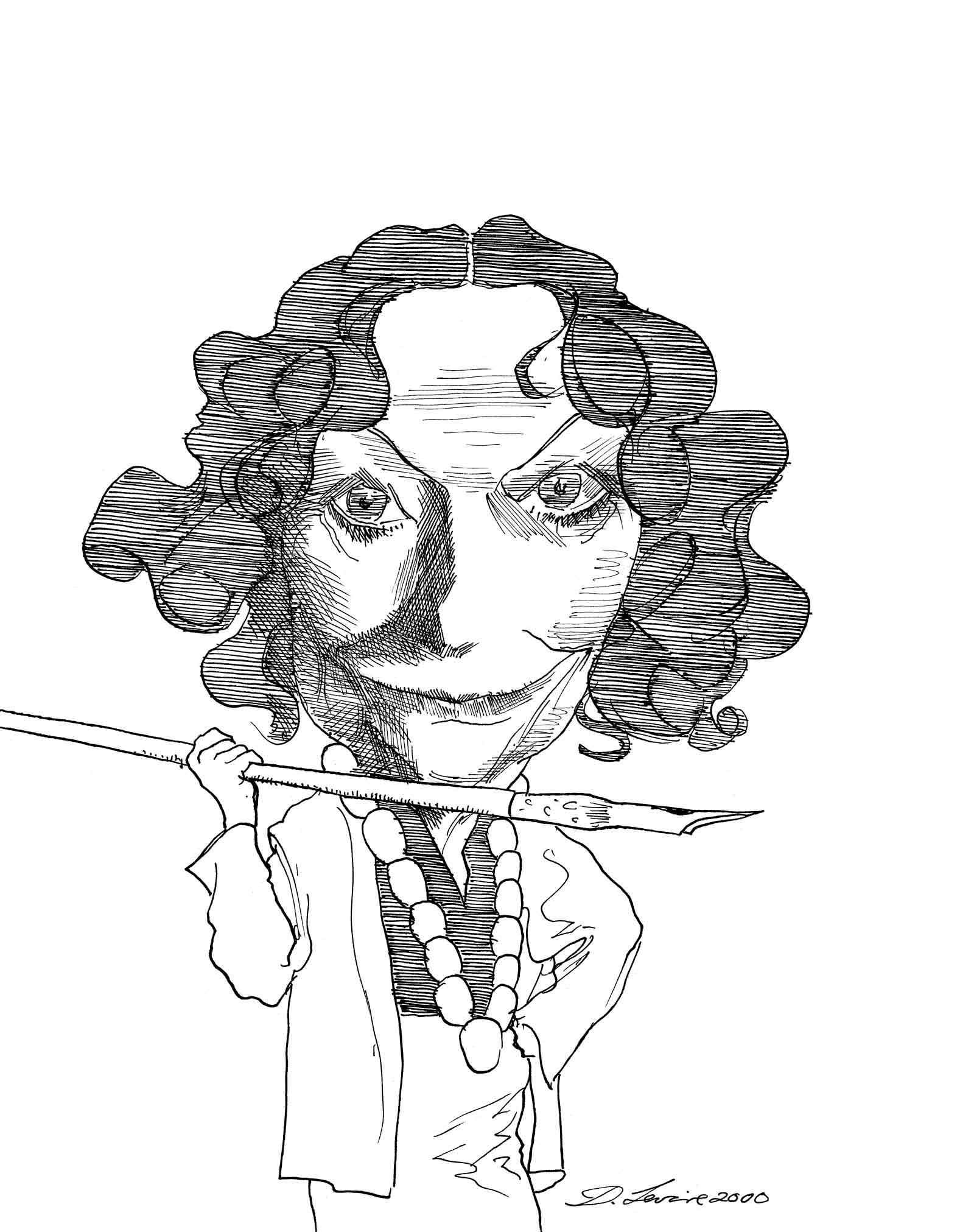

As the Republican Convention gathers in San Diego, many middle-aged and more than a few elderly fellows are rousing themselves into a passion about a woman’s right to abortion. Of course, Pat Buchanan, Rep. Henry Hyde, and the Rev. Pat Robertson have never missed a period and yet they have much in mind for young women who have done so and placed themselves and their future in a distressing state.

The legislating men are of interest because of their inexperience in the matter at hand. They seem to believe girls, as some may still be spoken of, have reached their pregnant condition quite alone, out of reprehensible indulgence or folly or criminal impulse, and so must live with the consequences, that is to give birth. A gun went off, you might say, but the hand that pulled the trigger is of no moral, religious, or legal concern. Can it be that the San Diego gentlemen were themselves free of the raging, insistent testosterone of the male in youth and beyond? Or perhaps they feel that when the testosterone bullet hits the girl, the man is acting in a sort of metaphysical self-defense. In any case, he is acquitted and the penalty, if you like, is hers alone.

It would be honorable for the Republican platform to consider the following plank—a heavy piece of wood indeed. In their frequent suggestions for constitutional amendments, as if they were a corner stoplight, they might propose, on behalf of the contested unborn, a command that young men remain celibate until marriage. The Celibacy Amendment deserves the floor.

The nation’s sons are a valuable resource, but if our sons willfully break the Celibacy Law and, to use an inspired phrase of ancient coinage, “knock up” our daughters, the fate will be forced marriage and active fatherhood. For many it will mean leaving high school or college or law school, and perhaps pumping gas to buy the crib, the mashed food in little bottles, and the first refrigerator and rearing the slowly maturing human child, once unborn but now born in partnership with whatever pretty, or passable in the dark, face was in the back seat of the car some time ago.

The lawmakers are not likely to know personal hardship from the Celibacy Amendment. Most are married and too busy even to take time out for an hour or so in a motel. They are in a punishing mood and history is on their side. Unmarried women have inflicted terrible tortures on their own bodies, hoping to undo or to conceal. When that failed, as it usually did, society often gave them abandonment, disgrace and, in some cultures, death.

Advertisement

Men of imagination have understood the appalling dilemma for the woman that may follow a night or two of pastoral young love under a summer sky. It would be a spiritual advancement in San Diego to remember Thomas Hardy’s Tess and Tolstoy’s Resurrection with the peasant girl and the prince visiting his estate. There are profound moral reflections therein about the sweetness and naturalness of love and the sometimes awesome consequences for her.

However, a rich political life does not find time for the wisdom of fiction. And so in the mundane interest of equity, the anti-abortion zealots would honor their obsession by proposing a sort of balancing of the human budget: a Celibacy Before Marriage Amendment to the US Constitution. Let us see how that goes down.