The first time I saw Lanford Wilson’s 1987 play Burn This, currently in revival at the Hudson Theatre, was in 2004 at the Boise Contemporary Theater; I was sixteen. Midway through the play’s first act, Pale pounds on and then bursts through the door to Anna and Larry’s apartment. Anna is a dancer-turned-choreographer; Larry is her roommate. Both are mourning Robbie, a dancer who, along with his boyfriend, has recently been killed in a freak boating accident. Pale is Robbie’s older brother. It’s Anna who answers the door, and so it’s to Anna that Pale, drunk and high (“Yeah, I did maybe a couple lines with Ray,” he says; and then, in all sincerity, “it don’t affect me”), monologues.

I don’t remember moving during this scene, during the rest of the play. I remember Pale’s entrance striking me like a hand to the cheek, so that on the surface I was all aflame, below, numb meat. And I remember that at some point during this scene, I felt a kind of dip in the pit of my stomach.

Maybe it was as early as Pale’s second speech about the perils of parking. (“But I’m trying to parallel-park in the only fuckin’ space a twenty-block radius, you don’t crawl up my butthole in your shit-green Trans Am and go beep-beep, you know?”) Maybe it was the moment, later, when Pale, who has been loud and vulgar but also somehow gregarious, turns, at the suggestion that he didn’t know his brother, for the first time truly mean. (“Oh, beautiful, I love that. You’re going to be a cunt like everybody else?”) Certainly it was before Pale starts sobbing, before he says to Anna, “You almost got no tits at all, you know?”, before he starts listing physical complaints—“My gut aches, my balls’ are hurtin’, they’re gonna take stitches on my heart; I’m fuckin’ grievin’ here and you’re givin’ me a hard-on”—before he tells Anna “I’m gonna cry all over your hair,” and then does.

I know certainly because the tits line, plus the hard-on line, that’s what confirmed it. I was sixteen and I’d never been past second base but I’d sensed that Pale’s verbal violence had to it a sexual subtext and lo, that tits line proved me right.

*

Burn This has two acts and one set, Anna and Larry’s apartment, the latter a restraint that allows for dilation elsewhere: in Pale’s monologues most notably, but also in time. More than a month passes between the first and second scenes of the first act; over two months separate the first and second acts; another month passes before the play’s final two scenes.

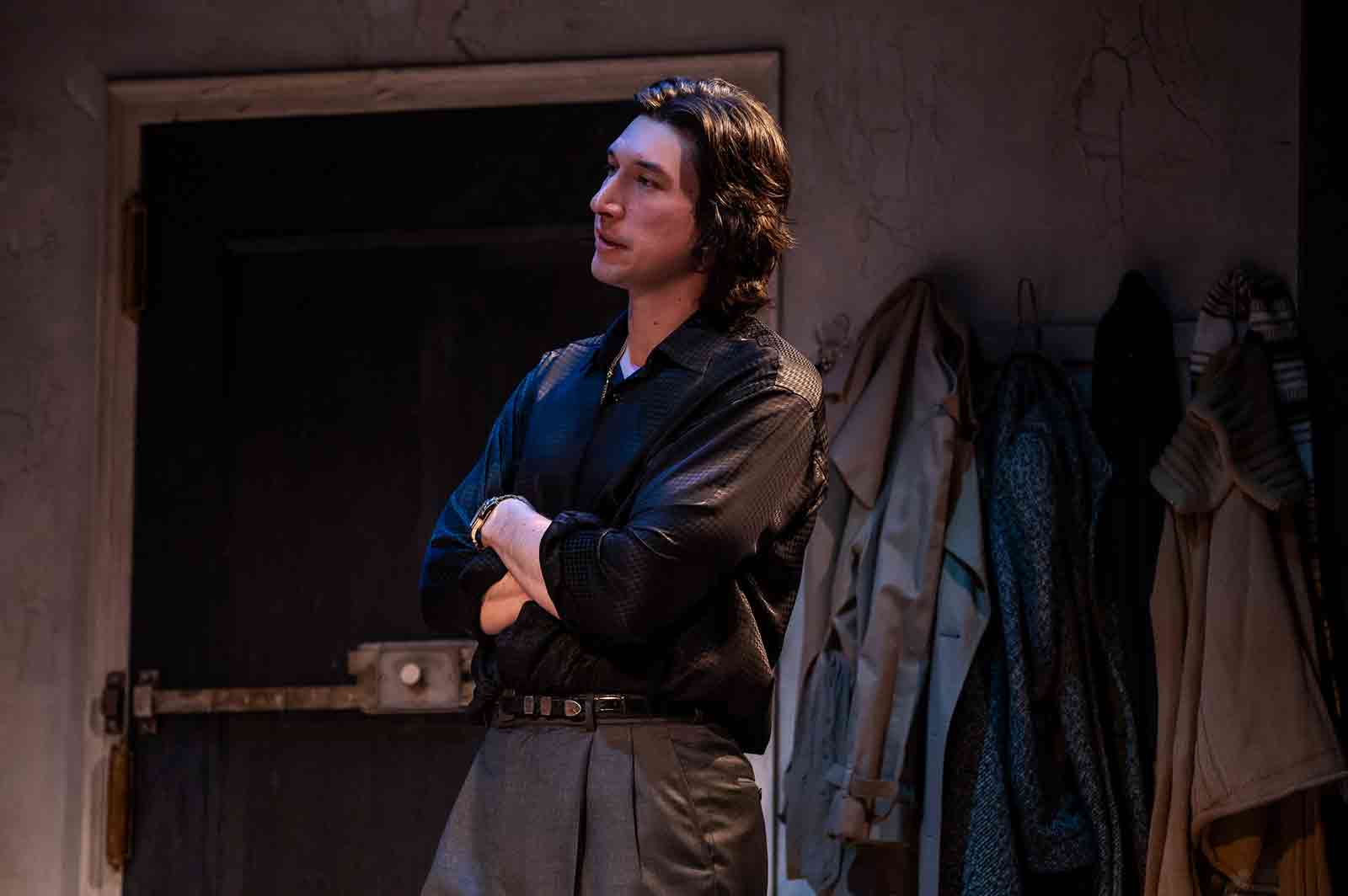

The first act is all set-up and collision: Anna, played in the revival at the Hudson by Keri Russell, is just back from Robbie’s funeral, where she has been mistaken by his conservative Catholic family—“aunts and uncles for days,” none of whom seem to have known he was gay, or ever seen him dance—for “the bereaved widow.” Her boyfriend, a rich, handsome screenwriter named Burton (David Furr), comes by the apartment; he’s been on vacation in Canada and has only just heard the news. Burton is confident, generous, kind, and self-involved. Anna quickly sends him away; it’s Larry she wants to confide in. Anna and Larry talk, and then the lights go down. When they come up, it’s a month later and Pale, played by Adam Driver, is pounding on the door.

The second act is all fall-out and resolution: Anna and Burton are back from a New Year’s Eve party. Anna’s been working on a new dance; Burton’s been working on a script. First Larry (Brandon Uranowitz) bursts in, back from spending the holidays with his family. Then Pale does. He’s drunk of course, staggers to the bathroom first thing; when he comes out, he falls into Anna, kisses her. The kiss is proprietary, and hungry, and desperate; for all the times Pale breaks down into actual tears this is, to my mind, his moment of greatest vulnerability, his most honest expression of need. In the two months since Pale first burst into Anna’s apartment and cried in her hair and slept with her, they’ve only seen each other once, and then only accidentally. Pale and Burton get into a physical fight, and in the end, it’s Burton whom Anna throws out.

*

Pale, like many a traditionally socialized heterosexual American man, carries with him the threat of violence. And, as in many a more traditional American love story, male force is the prelude, perhaps even the key, to female seduction. Popular culture is littered with examples of women bullied, more and less violently, into sexual relationships that they come—in some cases, almost immediately—to enjoy. Romantic comedies so often pitch as cute behavior that would, in real life, obviously present as creepy that this problematic trope has been the subject of an Onion article, a scientific study, and a Netflix show in which the twist is that the ostensible romantic lead actually is a stalker.

Advertisement

Think of Rocky Balboa’s first kiss with his beloved Adrian. It’s played as pure romance, despite the fact that Adrian several times professes her discomfort and tries to leave. But Rocky refuses to be dissuaded. He physically bars her path, removes her glasses and hat, and declares, “I want to kiss you. You don’t have to kiss me back if you don’t want. I want to kiss you.” Then he makes his move. (The description beneath the YouTube video clip of this scene reads, either defensively or credulously, “When this was filmed, the actress for Adrian was sick which [sic] a cold which partially contributed to the way she hesitated.”) The audience is meant to take Adrian’s silence—and the fact that she does, eventually, begin kissing him back—for assent.

Ang Lee’s 2007 historical drama Lust, Caution presents a more extreme example of the same dynamic: a woman coming to want what a man has forced upon her. The film, set in Hong Kong and Japanese-occupied Shanghai in the late 1930s and early 1940s, centers on the relationship that develops between Mr. Yee (Tony Leung), the head of the Japanese puppet-government’s secret police force in Shanghai, and Wong Chia Chi (Tang Wei), a member of a Chinese resistance cell. Their first sexual encounter can only be characterized as assault: Chia Chi begins to undress, slowly, intending to titillate Yee with a languorous striptease; without warning, Yee crosses the room, throws Chia Chi against the wall, rips her dress, shoves her face-down onto the bed, removes his belt and first hits and then ties her hands with it, before roughly entering her from behind. Throughout, she is screaming in protest.

The scene is complicated by the fact that Chia Chi has seduced Yee in order to set him up for an assassination attempt. Is that why, after Yee leaves, Chia Chi, lying on the bed, her dress torn, her lipstick smudged, smiles faintly? Because her honey trap has been successfully sprung? How then to explain the sex scenes that follow, many of which read not only as consensual but also, variously, as passionate, as tender? How to explain Chia Chi warning Yee, at the last minute, of the assassination attempt, a decision that leads to her execution, and the execution of her comrades, their death warrants signed by Yee himself?

Here’s how I explain it: to be socialized as female is to be told that a man knows your desire better than you do. If what a man wants to do is force you to kiss him, who are you to say you don’t want to be kissed? If what a man wants to do is hurt you, who are you to say you don’t want to be hurt? I do not mean to deny female agency; I mean to contextualize it. Can a woman willingly submit to a man? Yes, and in any number of ways, the gesture ironic, or playful, or erotic. But she inevitably does so under the umbrella of patriarchy, her desires not defined, but in some way colored, by its shadow. In her essay “Lust Horizons,” Ellen Willis asks, of individual sexual proclivities, “Why do we choose what we choose? What would we choose if we had a real choice?” Neither Adrian nor Chia Chi have a real choice. Is it so surprising then that what they decide they want ends up looking exactly like what they’ve been made to take?

*

Anna and Pale spend the whole of the play swearing they don’t want to be together either right before, or right after, having incredible sex. Both fear the vulnerabilities of intimacy—Pale’s second to last line is, “I’m real scared here,” to which Anna responds, “I don’t want this… Oh, Lord, I didn’t want this…”—but Anna has practical as well as emotional reasons to be wary.

Pale’s energy is ungovernable; this attracts Anna in part because her life has been formed around the practice of governing her own. Dance, of course, is about control; but also, as the member of a company, Anna’s life outside the studio, too, has been circumscribed, managed. “She’s never,” Larry notes, late in the second act, “had to even carry her own passport or plane tickets.” There’s the sense, when Anna and Pale collide, both that she’s seduced by the possibility of living wildly, and that she worries she’ll be tempted to give her life up to him. It is, after all, what she knows how to do.

Advertisement

But living wildly is dangerous, and that ungovernable energy Pale brings to the project is also genuinely disturbing. Pale manages a restaurant with mob connections; he says cunt once and uses f-words constantly—fuck and also fruit and faggot. His hand, when he first appears in Anna and Larry’s apartment, is bandaged: he punched a man in the face at a bar because the guy wouldn’t shut up.

As Pale, Driver rants at paragraph-length with impressive facility; his Pale is eloquent and crude and blustery and operatic and often funny. He’s appropriately large, both in the sense of length and depth and breadth, and in the way his body insists on taking up even more space than it properly needs, his stance wide, his arms either flung out or held akimbo. Driver does look a bit young—I’d bet money that he’s lived his thirty-five years more judiciously than Pale has his thirty-six—but the slapdash angles of his face do suggest wear and tear; you’d believe it if there was a line about Pale’s nose having been broken.

A bigger problem than his youthfulness is the fact that Adam Driver is a famous actor, and seeing a famous actor on stage—that is, in the flesh, rather than on screen—is exciting in a way that has everything to do with who the actor is and nothing to do with the character he is playing. Casting someone known tends, inevitably, to pull the audience out of the fiction of the play; the audience is constantly being reminded of what it is they are known for. (Burn This is hardly the only Broadway play to face this particular hurdle; without celebrities, shows often can’t draw an audience big enough to make back their initial investments.) A Pale with a lower public profile—Matthew Clark in that 2004 Boise Contemporary Theater production; Gene Gillette in a version I saw in 2008 at Shakespeare Santa Cruz—can succeed or fail on the strength of his performance. He doesn’t have, for competition, an actor’s already formed persona. Driver’s Pale does. “I think you’re dangerous,” Anna tells Pale in the second act, and she’s right, he is. But Adam Driver isn’t, and so it’s only occasionally that Adam Driver’s Pale can be. And if the audience doesn’t believe in Pale as a real threat, neither Anna’s fear, nor her desire, feel as heavy, as literally pressing, as they ought.

And the audience, at least on the night I saw the play performed, seemed incapable of separating Pale from Driver, the character from the endlessly memed actor playing him. (I wonder if the Times’s glowing review of Driver’s performance can in part be attributed a better behaved crowd.) They respond to Pale’s misogyny and his homophobia and his extended meditation on the varied destinies awaiting trees headed for the paper mill the way one would expect an audience to respond to a leader of the First Order speaking the line “And you’re stuck in the ground, you can’t go nowhere, all you know is some fuckin’ junkie’s gonna wipe his ass and flush you down the East River”: by giggling nervously. Even Pale sobbing, his head covered, in shame, by an afghan, elicited uncomfortable laughs.

Driver’s Pale has his moments, each a credit to Driver’s ability to give the character a specificity so convincing it temporarily overwhelms the cultural context his presence summons. Explaining the origin of his nickname—his name is Jimmy; he’s called Pale because of his fondness for VSOP—he draws the o and then the a out in Very Special Old Pale, whipping the listener around each vowel like a very fast car around a very sharp corner. Commenting on Anna’s small breasts, the punch he gives the voc in provocative (“No, that’s beautiful. That’s very provocative. Guy wants to look, see just how much there is”) makes the play’s stage direction here—“Not looking at her breasts or touching them”—all but moot. Maybe if the audience were forced to close their eyes—sure, you’d lose the physicality of Driver’s performance, but you’d also be allowed to leave behind the baggage that comes with it.

Keri Russell is less hampered by her fame—not because she’s less famous, but both because her most famous role (Felicity) is further in her past, and because the role for which she was most recently acclaimed (The Americans’ Elizabeth Jennings) was that of a serial impersonator. And the icy remove that made Russell a convincing Russian spy makes her also convincing as a too disciplined dancer. Her desire for control is palpable; what Russell’s Anna is missing is the competing desire to release it. Anna should be scared of Pale not only because he’s scary, but also because she’s afraid of what she’ll let herself give up for him. The moment, at the end of their first scene together, when she kisses him, when she lets him kiss her, should begin in sympathy—“don’t break your heart,” she tells Pale, who’s been crying—pass through concession, and end in relief. It’s an admission: I want this, too. I want this more than I don’t want this. In the performance I saw, Russell played it like Anna was making a decision.

*

From certain angles, Burn This reads as an elaborate joke about the curse of straight sexuality, an exquisitely compelling troll. Anna begins the play with a perfectly nice boyfriend she seems to like well enough and whose repeatedly rebuffed marriage proposals she’s almost decided to accept. Then Pale shows up, drunk and destructive, the real man she never knew she always wanted.

Two elements push against this reading. The first is the immersive specificity Driver’s performance occasionally offers. Pale should be played fearlessly, that is to say without fear of losing the audience’s sympathy; if he’s immediately appealing, the play loses its emotional stakes. If the audience makes it difficult for Driver to access this specificity more often, the moments when he does suggest what he could have done with Pale had he been only just breaking into film, as John Malkovich was in 1987 when he debuted the role, instead of being an already established star.

The second is the fact that, in the month that passes between first scene of the second act and the last two, Anna finishes choreographing what the play tells us is an exceptional dance, a personal dance, a dance about her and Pale. “I’ve never,” Larry says, trying and failing to describe it, “seen a man on stage in a dance—it’s a man and a— It’s very startling. It just has to do with the center of gravity, I guess, but… or something. I mean it’s a regular man—dancing like a man dances—in a bar or something, with his girl. You’ve never seen anything like it.” Pale’s violence unlocks Anna’s desire, but it’s Anna who makes, of her experience of that desire, art. In this way, their relationship is more than the classic coupling of beautiful, intelligent woman with magnetic asshole. One stereotype—a man knows a woman’s desire better than she herself does—is paired with the inversion of another; here, it’s the man who acts as the woman’s muse.

My first experience of Burn This was just that: an experience, that is to say formative and immediate. It resisted, then and now, examination. And yet I’ve been trying, in the months since the Harvey Weinstein allegations broke, trying, despite the resistance I encounter, to examine that experience. I’ve been trying to examine the many formative cultural experiences—in many cases shaped by alleged sexual predators—that taught me to expect male sexual attack, and to steel myself against it, even—especially—when the desire that fueled that attack was reciprocated. To resist until I met a man whose attack overwhelmed my resistance. Burn This doesn’t upend this scheme, but it does play provocatively within it. It suggests that artistic release requires emotional release. It admits that it is usually through a kind of violence that women have been allowed to access the latter.

At the core of Burn This is the question what would happen if I let myself have what I want? The play knows that, most of the time, we—women especially—want what’s bad for us; or rather, that as soon as we want something, we’re told it’s bad for us. That’s why Pale has to be a train-wreck of charisma; you have to know you should look away, maybe go get some help—and that has to be impossible. The source of the play’s singular pleasure is in the answer—go ahead and find out—it still insists on offering.

Burn This is at the Hudson Theatre, New York City, through July 14.