A woman, half of her face pressed into the mattress, is curled up in the fetal position on a metal bedstead; another lies on white sheets, her legs spread wide, the skirt of her yellow dress bunched up around her waist; a third, a bare-legged schoolgirl, still wearing her uniform, squats over a plastic bucket. Paula Rego’s potent Triptych (1997–1998) was created as a response to the 1998 referendum in Portugal, when the government failed to legalize abortion thanks to opposition from the Catholic Church and pro-life campaigners. Rego is vehemently pro-choice, and has spoken of the desperate fishermen’s wives, often mothers already several times over, who’d turn up at the house Rego shared with her husband when they were living in the Portuguese village of Ericeira in the 1960s, begging for money for backstreet abortions, not to mention the occasional body, stomach swollen like a cow’s, found floating in the harbor from one gone wrong.

In both Triptych and the accompanying Abortion Pastels (1998–1999), Rego’s subjects are physically vulnerable, but it’s clear that she’s not painting victims. Rego has depicted women who’ve taken action to wrest back control of their lives, women who’ve made a choice. Indeed, the openness of both their legs and their clear-eyed gazes is strangely inviting, tingeing these portraits with a disquieting eroticism. The theme permeates Rego’s work: sex and violence, as seen, more often than not, through the prism of female experience. Perhaps because we are increasingly aware of just how precarious abortion rights actually are, but these particularly arresting pastels dominate “Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance,” an exhibition of over eighty works that has recently opened at the new MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, England.

Although the Portuguese-born artist has long made her home in North London, working out of her studio in Kentish Town, this is the first major retrospective of Rego’s work to appear in England in decades, and its curator, art historian and former director of the Whitechapel Gallery Catherine Lampert, has done an excellent job in both charting the trajectory of Rego’s intriguing career, while also illuminating the political perspective behind the scenes on display. Some have struggled to describe Rego’s work as feminist, pointing to her depictions of women in the thrall of overbearing, physically powerful men—the glowering Mr. Rochester, for example, in her series of pictures inspired by Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (2001–2002)—none of which, incidentally, appear here, suggesting an attempt to move beyond any idea we might have of Rego as merely an illustrator of gothic fairytales.

Rego herself has never thought of herself as anything but a feminist, her childhood in Portugal having exposed her to a society in which women had little agency of their own, and suffered frequently—viscerally and painfully—as a consequence. “It is not often given to women to recognise themselves in painting,” wrote Germaine Greer of Rego’s images back in 1988, “still less to see their private world, their dreams, the insides of their heads, projected on such a scale and so immodestly, with such depth of colour.”

Despite some not insignificant early success—Rego won the Slade’s Summer Composition competition in 1954 while a student at the famous London art school (something she still considers her greatest achievement, despite all the accolades heaped on her work in the years since), and had a noteworthy solo show at the Galeria de Arte Moderna of the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes in Lisbon in 1965—it was only in her fifties that she began producing the magisterial pieces that made her name. Rego turned her attention to her own psyche and intimate lived experience, channelling her interiority and the dynamics of her interpersonal relationships into the animals and the women she painted. Recognizing this, Lampert has curated a show that pulses, robustly and not a little unsettlingly, with female power, pain, and terror.

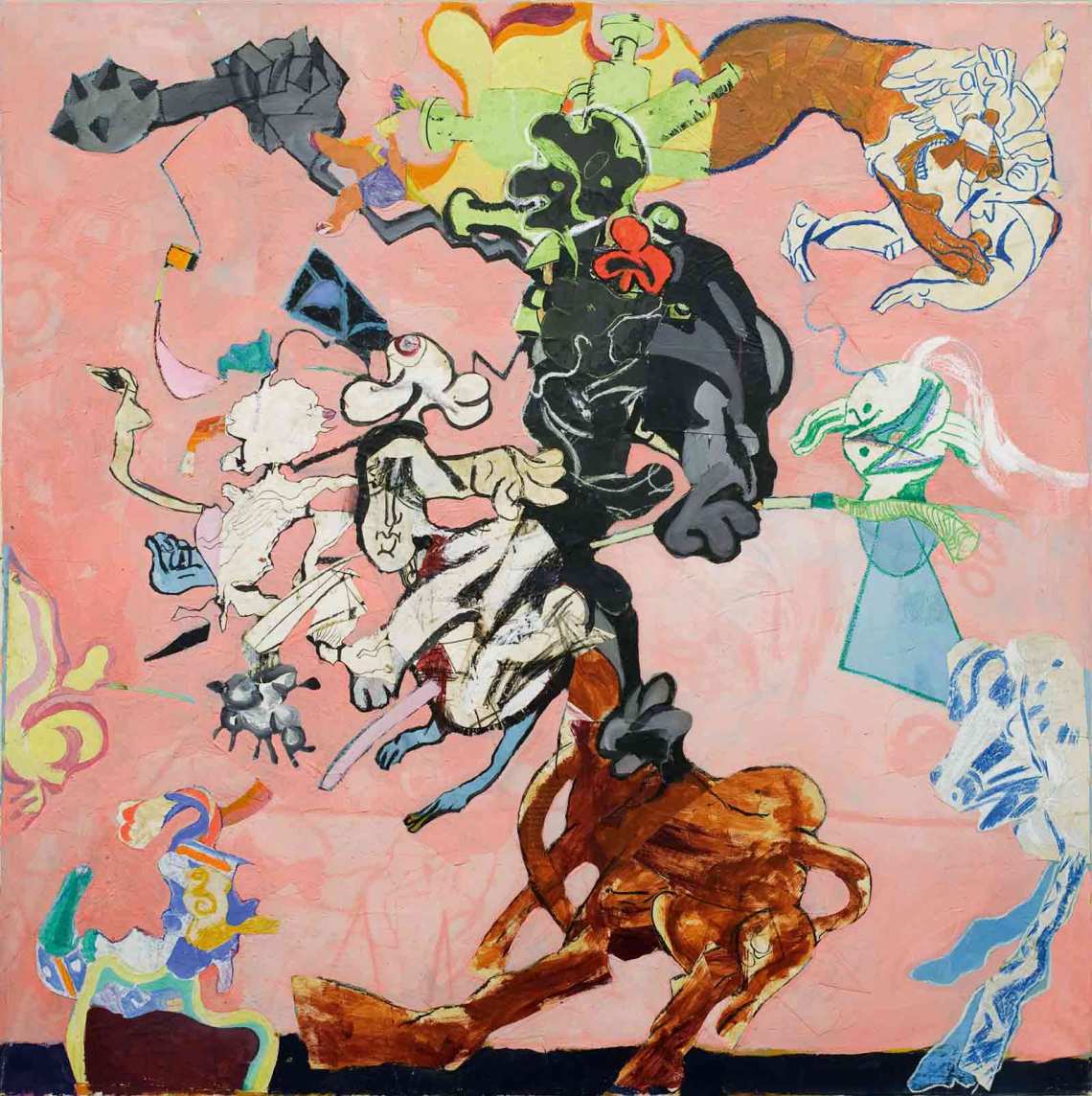

Linger in front of any of the eight brightly-colored, surreal canvases in the first room—painted between 1960 and 1966, each a response to the Portuguese politics of the period, shaped by the fascist dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar—and we’re a long way from the recognizable figures of Rego’s more recent work though. In Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960), the leader—a rotund white body supported by long claret-colored legs, a trunk-like mouth curled outward—is bent over, spewing on his own feet. Standing tall beside him, in the center of the image, is a figure—a mass of what looks like rust-colored pubic hair suggests a female body, but hanging below this is what looks like a single, hairy testicle. The spindly-limbed figures in The Exile (An Old Exile Dreaming of His Youth) (1963), meanwhile, are reminiscent of pieces by Joan Miró, while on first glance I might have guessed that some of the other canvases around them were the work of Picasso.

Advertisement

While these early painting-collage hybrids don’t tell us much about Rego herself (beyond her obvious left-leaning anti-authoritarianism), they do tell us about the world she comes from. Despite the stylistic differences between these and her later work, they unquestioningly exist on the same continuum: Rego sees each one of her “pictures,” as she calls them, as having a story to tell. Regicide (1965), for example, depicts an earlier political trauma, the 1908 assassination of Portugual’s King Carlos I and his elder son. Out of the confusion and chaos, figures slowly materialize; cutout paper glued on a bright, electric-blue background. Surely that’s the assassin looming low in the right-hand corner, a face eerily all but devoid of features? The open carriage-turned-funeral cortège is the only object immediately identifiable. In it sits a distorted figure, all bulbous pink flesh, beside whom lies what on closer inspection seems to be a crumpled body, its face already a contorted death mask of grays and blacks. Meanwhile, Rego’s one-piece triptych of striking black-and-white tones, When we had a house in the country we’d throw marvelous parties and then we’d go out and shoot negroes (1961), is a damning indictment of Portugal’s colonial brutality in Angola.

From here, the work on display jumps fifteen years, to 1981 (the Salazar dictatorship ended in 1974). In Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories (2017), the award-winning documentary directed by her son Nick Willing, Rego describes the missing decade plus as a period of “treading water”: coming to terms with her husband (and fellow artist; they met at the Slade) Victor Willing’s incapacitation by multiple sclerosis, resettling their family in London after living in Portugal, all while desperately trying to make ends meet; she did some teaching at the Slade but the family often survived off grants from the Gulbenkian Foundation. Understandably, Rego was too depressed to do much painting. It was only after she entered Jungian analysis, in 1973, that something changed. Encouraged to re-visit early experiences, at the tail end of the decade she spent time in the British Museum reading room, re-acquainting herself with the stories that had been a staple of her own childhood. The change that then emerged in her art of the 1980s is visceral. Gone is the surrealism of her early collage pieces, and with it her depiction of sweeping national concerns. Instead she turns her focus inward, transforming her own lived experience into large-scale acrylic, then later pastel tableaux, the figures therein instantly recognizable, if not always strictly situated in the realm of the real.

Lampert’s inclusion of the Henry Darger-inspired The Bride (1985) bridges the gap. A busy fusion of pinks and blues, it gestures both backward—to the less successful, cartoon-like images Rego toyed with during the 1970s—and forward, with the early appearance of the doll-like figures and animals that are now synonymous with her work. Three images from her “Girl and Dog” series on the opposite wall—Snare (1987), Two Girls and a Dog (1987)—along with Sleeping (1986) are spun from fairytales and folklore. But the paintings also mine her own psyche and experience: her ambivalence about her relationship with the increasingly infirm Willing comes to the fore in these human and animal pairings. Torment and tenderness are both visible amid uncanny Dalí-esque dreamscapes. There’s also more than a hint of the arid Arizona wastes Dorothea Tanning incorporated in paintings like Maternity (1946–1947). Here Rego’s landscapes are barren but for a few talismanic objects: a tiny horse-drawn carriage; a crab lying on its back, its legs in the air; a claw hammer; a lone daisy. A field day for her analyst, no doubt.

But when it comes to the abortion series in the next room—the heart of the exhibition—realism dominates—not least because the portraits on these walls don’t feature any extraneous detail, the women she depicts are themselves enough. “I tried to do it full frontal but I didn’t want to show blood, gore, or anything to sicken,” the exhibition catalog quotes Rego explaining, “because people wouldn’t look at it then. And what you want to do is make people look, make pretty colors and make it agreeable, and in that way make people look at life.” Indeed, I found it hard to tear my eyes away. The paintings were first exhibited at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, then later, in the run-up to a second referendum in 2007—this one successful—reproduced in the Portuguese press, useful “propaganda,” as Rego herself explicitly describes the images, for the pro-choice lobby.

Advertisement

Rego is certainly an artist who knows how to make her audience look, even when the shocking or terrifying nature of her chosen subject should, by rights, make people want to close their eyes and turn away. Her etchings graphically depicting female genital mutilation look like scenes from a tale of Gothic terror, something written by Angela Carter, perhaps, or Samanta Schweblin. Circumcision (2009) and Mother Loves You (2009) are two particularly monstrous images of pain and torment. In the former, two white women hold down a black girl, while another figure—a grotesque steampunk villain—looms over the captive’s spread legs. The same tableau appears in the latter, though this time the attacking figure appears to be a naked, distorted wooden mannequin, bared teeth, leering eyes, and what looks like a yawning-mouthed animal between her thighs—that or nightmarish vagina dentata.

As in so much of her work, the phantasmagoric takes on something of the real, a nightmare brought to life, or the turmoil of a psyche revealed. Rego’s well aware that women’s bodies are sites of trauma. She recounts her own birth, for example, as a horror story: her mother labored for three days, at the end of which she, the baby—“this carcass,” as Rego pointedly describes herself—was “dragged” out, ripping her mother’s bladder in the process. Rego’s work is dense with symbolism, but all in service of portraying the realities—as unpalatable and grotesque as they sometimes are—of the female body.

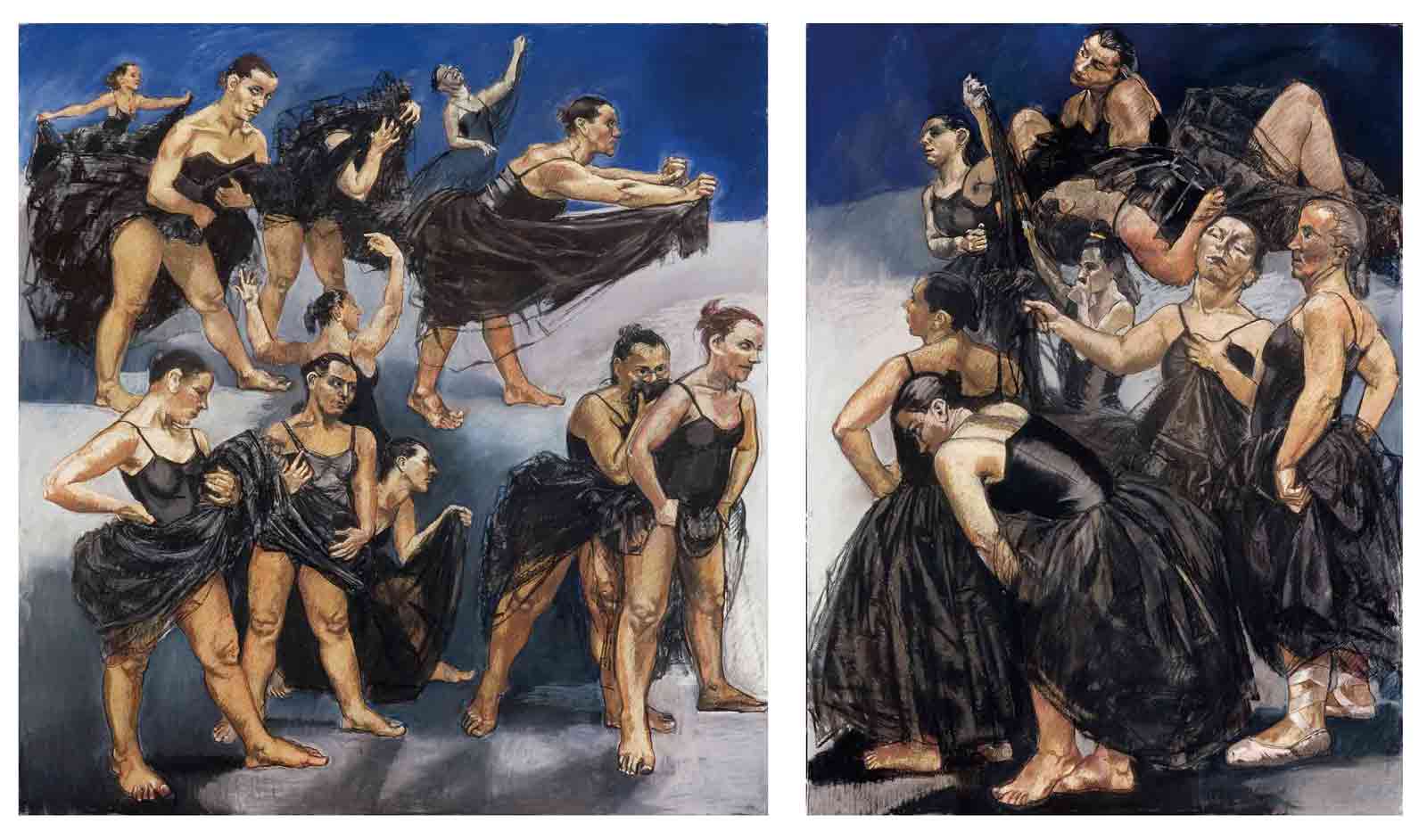

Rego is interested in female subjects who wear their stories on their bodies, whether it’s a teenage girl doubled over in pain as she aborts, or the sturdy-limbed, sweat-slick, muscular middle-aged ballerinas of Dancing Ostriches (1995). “A real lumpy, bumpy woman who has sinned,” she told a journalist who asked her why she so often depicted mature, unglamorous women, “it’s an aspect of the human condition that has always appealed to me.” The interest is clearly not new—her pencil drawing Dog Woman (1952), half-woman, half-canine, crawling on all fours, its mouth open in a snarl, which Rego drew the year she entered the Slade, hangs in the corner of the central room, presiding over the entire show. It took another forty years before she drew her “Dog Women” series, full pastel portraits of women posed like beasts. In many ways, Rego has long been an artist ahead of her time, but now is certainly the right moment for this retrospective.

“Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance” is on view at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, England, through September 22.