One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate.

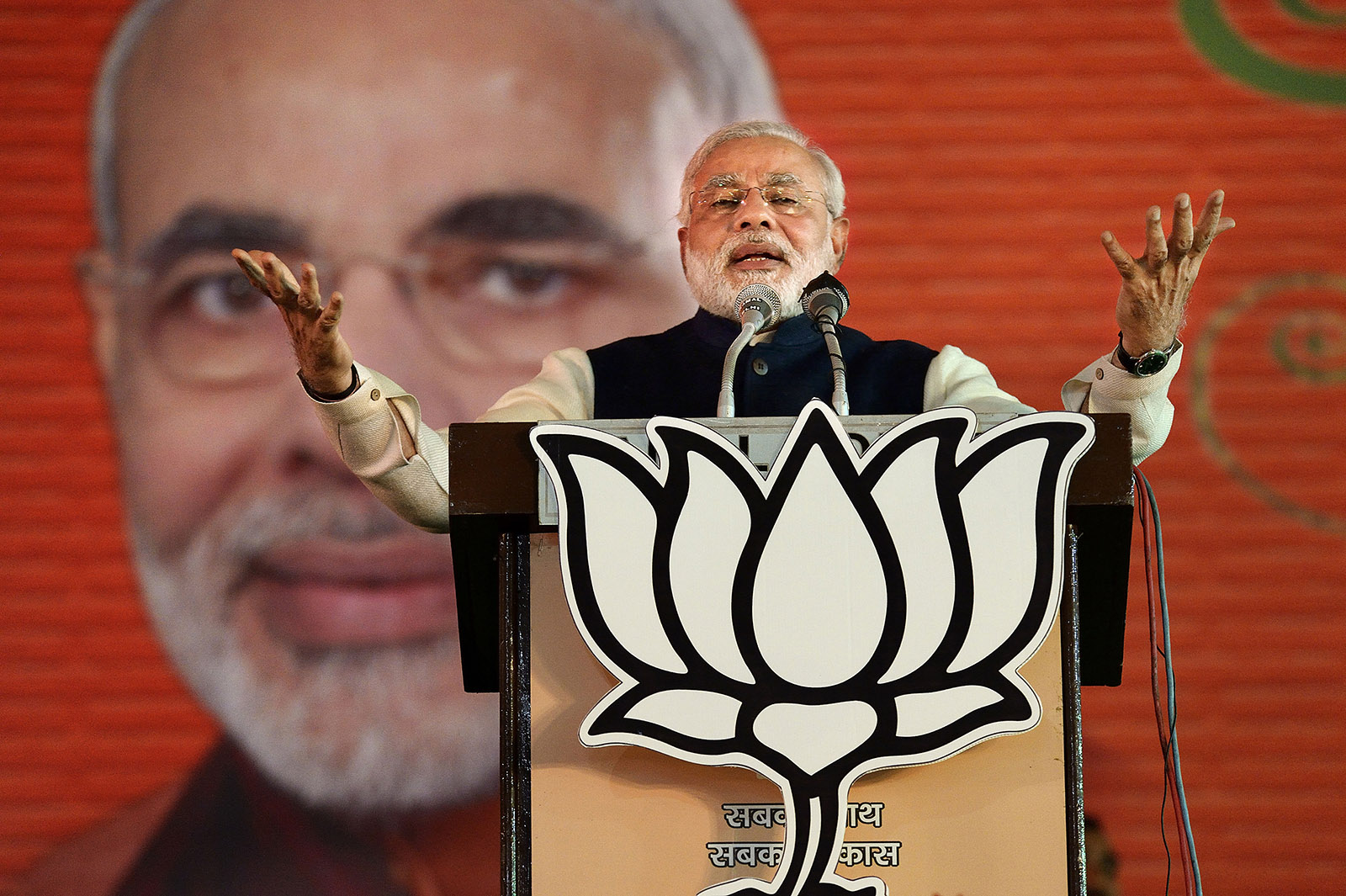

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s triumph on May 23 was conclusive. His Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won more than 300 of the 543 seats in the lower house of Parliament. But Modi had spent the last five years letting India down. Very little he had said on the 2014 campaign trail turned out to be true and virtually nothing he promised was delivered.

The prime minister had pledged to create 10 million jobs each year, but under him the country has experienced its highest rate of unemployment in forty-five years, with more younger and better-educated people than ever before stranded helplessly. His hasty decision to void the largest currency bills, in 2016, removing more than 80 percent of the money in circulation was supposed to curb corruption, but it cost more than a million jobs and did nothing to prevent graft in India or make business more transparent.

The year after that, a value-added tax was rolled out with great fanfare but inadequate testing; it quickly became a nightmare for small businesses, hurting some of the very people the government had claimed to want to help. Farmers, by then earning their lowest incomes in eighteen years, marched on Delhi carrying the skulls and bones of fellow rural workers who, they said, had died by suicide.

Whereas Modi had pledged “acche din,” or good days, for all, the only people who seemed to be enjoying them were the crony capitalists who had bankrolled his victory. Even as the votes were being counted on results day in 2014, India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, a staunch supporter of the prime minister, added almost $1 billion to his wealth as his holdings rose in value. Another billionaire associate, Gautam Adani, gained $600 million.

Other BJP promises—to eliminate open defecation in rural India, develop a hundred technologically advanced “smart cities,” and tackle pollution in the River Ganges—remain unfulfilled. Modi’s pledges, it soon became clear, were lies.

India under Modi was no longer the world’s fastest-growing economy. And whatever upward mobility was anticipated thanks to social welfare programs implemented by earlier governments could no longer be taken for granted. The prime minister’s opponents fought for a more equal society, but Modi himself, like strongmen elsewhere in the world, could only prosper in an unequal and divided one. And yet, Modi won again.

*

To those who had paid close attention, his emphatic victory had always been the only possible outcome to the election.

These elections, reported the Centre for Media Studies, a non-partisan think tank in New Delhi, had been the most expensive “ever, anywhere.” In an election that was fought between six national parties, and many smaller ones, the BJP’s electoral juggernaut received an estimated 45–55 percent of the estimated 55,000 crore rupees (nearly $8 billion) that was spent on this election. Their main rival, the Indian National Congress (INC), accounted for an estimated 15 percent of the total spent. More than half of Modi’s war chest came from anonymous donors. Who these people are can only be guessed at, but since 2016 the BJP has received almost 93 percent of corporate donations, leaving the remaining 7 percent for the other national and state parties to fight over.

Before the campaign had even started, the BJP had spent more money on ads than the previous government did in ten years. And when it came to electioneering, they were able to rent all the available helicopters and private jets in India, leaving the opposition stranded on the ground.

The mainstream media, particularly cable news, amplified the BJP’s message and drowned out the opposition. They editorialized the news, started rumors, and spread lies. Truth was an illusion, and everything was propaganda. The INC’s leader, Rahul Gandhi, was denounced as a fool and even a foreigner, while Modi, in a tradition that will ring familiar to people in Russia and China, was glorified as the great leader.

While Gandhi gave several interviews to a range of media, Modi gave one interview to a giggly Bollywood actor in pink trousers and another to a TV host who asked if he had written any poetry in the last five years. Sharp-eyed viewers saw that in Modi’s hand was a list of agreed-upon questions.

A survey conducted across eleven Hindi-language news channels later showed that Modi and his closest associate, Amit Shah, had received two and a half times more airtime than Gandhi and his sister, Priyanka Vadra, who campaigned for the party during the election. These same TV channels had presented Modi not merely as the frontrunner, but as the only choice.

Advertisement

Finally, the Election Commission of India, an institution once widely admired for its stern neutrality, made repeated rulings in favor of the BJP. Although Modi violated its code of conduct at least six times, he was given a pass—even when he shouted at a major rally that his main opponent was the son of the most corrupt person in the country. He was referring to the former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who was assassinated by Sri Lankan terrorists in 1991.

The commission had let a TV channel dedicated to Modi continue to screen coverage of the prime minister through election day, even though this was breaking rules that prohibit political broadcasting during the election. Subscribers didn’t have to pay for the twenty-four-hour channel, which appeared in the menu options just before the elections, and then, as mysteriously, vanished when polling ended. The commission also ignored credible complaints of electronic voting machines being transported without security and then going missing.

Then, in July, a group of former senior civil servants sent an open letter to the Commission calling attention to numerous cases of voter exclusion. These elections, the experts said, were among the “least free and fair” in three decades.

What reason could India’s once famously feisty media and its once admired Election Commission have to behave in this way? The BJP got such an easy ride that it hardly mattered what Modi’s opponents did.

And while Gandhi was the obviously better choice, he wasn’t, necessarily, a convincing one. For years, Gandhi dithered about whether he would join politics, enjoying the unheard of privilege, in India, of deciding if he wanted to apply for a job. When he finally accepted, standing for election in 2004, he positioned himself as a foot soldier. He failed to do anything significant to change the country’s oldest party, his family’s party. The Congress was rotting from the roots upward, its representatives seen as incompetent, corrupt, and out of touch, yet Gandhi appeared to shrug and roll his eyes as though to say, Can you believe these people? He officially took over the party’s leadership in 2017, but it wasn’t until March 2019, less than a fortnight before voting was to commence, that he announced the main plank of his manifesto.

Nowhere was Gandhi’s lackadaisical attitude more obvious than in his own constituency of Amethi, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, which has elected Gandhis since 1980. “How long can a son keep winning on past legacy,” asked an Amethi voter interviewed by the Mint newspaper; the answer came with Rahul’s defeat on home turf in this general election.

*

“Rare is the strongman leader who grows less autocratic the longer he stays in office,” writes James Crabtree in The Billionaire Raj (2018), his acute examination of crony capitalism in India. And this might have been the case with India’s first autocratic prime minister, Indira Gandhi, daughter of the country’s founding father, Jawaharlal Nehru. In the summer of 1975, Gandhi’s advisers drafted an ordinance announcing a state of internal emergency to maintain the “security of India,” which, they falsely declared, was “threatened by internal disturbances.” Gandhi was reacting to a court decision that had invalidated her election, and jeopardized her position as prime minister, for irregularities committed in her own constituency.

“Before the decision was read out, the presiding judge was offered half a million rupees and promised a seat on the Supreme Court,” writes Kapil Komireddi in Malevolent Republic (2018), a searing portrait of the rise of Hindu nationalism in India. Over the next nineteen months, Gandhi’s critics were branded enemies of the state and arrested. The national media was censored and foreign journalists were expelled. Gandhi’s virtues were extolled on billboards, even as her son Sanjay experimented with population control by implementing the world’s largest sterilization program, first by offering incentives, such as cash and food, and then by having vulnerable men—including the rural poor, the urban homeless, and religious minorities—forcibly dragged to operation tents.

Gandhi might have remained in power indefinitely, but for a report by a Delhi think tank that assured her easy victory in democratically held elections. “Re-election would instantly purge the taint of dictatorship attached to her name in the West,” Komireddi writes. But in the elections that she called, Gandhi lost her seat and so did her tyrannical son.

Gandhi’s moment of vulnerability is unlikely to be repeated by Modi. If there’s one thing he would have learned from her experience, it is that indefinite power requires absolute control.

Modi’s election mandate gave him the power to form the government of his choice. And one of his first choices was to make a minister a man who had led the Bajrang Dal, a Hindu militant group that was linked to the murder of an Australian missionary, Graham Staines, and his two young sons in 1999. Staines ran a hospital and clinics for leprosy patients in Odisha state when a mob set fire to a van in which he and his children were sleeping, burning them alive.

Advertisement

The minister, Pratap Sarangi, was not charged with that crime, but in later years he was arrested for rioting, arson, assault, and damaging government property. Bajrang Dal was also named in a Human Rights Watch report on the 2002 anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat as one of “the groups most directly responsible for violence.” That same report accused the state’s chief minister, a former activist in the Hindu fascist RSS organization, of “tacitly justifying the attacks.” That minister was Narendra Modi.

Another one of Modi’s new ministers, Amit Shah, was charged with ordering three murders in Gujarat while Modi was chief minister there. One of the victims, India’s foremost investigative agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation, has alleged, was Shah’s partner in an extortion racket.

The opposition might have been expected to keep the ruling party in check, but when it became clear that the job was a thankless one, and that Modi was here to stay, Rahul Gandhi exercised the ultimate privilege: he walked out. In his four-page resignation letter, which became public on July 3, Gandhi took responsibility for his party’s electoral losses. Quitting the position of party president, he promised to remain a “loyal soldier.” But India’s oldest political party doesn’t need more footsoldiers; it needs a leader. As long as Modi is seen as the only viable option to run the country, he will present himself that way.

By abdicating his responsibilities, Gandhi reinforced an impression that he is above the gruelling, tedious business of building an effective opposition. His decision triggered a spate of resignations, the majority of which came from members of his close circle, men like him who have always enjoyed the perks of wealth and power. One even owns a palace. Losing their party positions is unlikely to make much difference to their lives, but to the Indians who didn’t vote for Modi and expect someone to speak for them in Parliament, it will make a critical difference.

The party is yet to elect a new leader, and the atmosphere of disarray and uncertainty benefits only Modi. The fragile state of the INC was illustrated earlier this month when thirteen of its legislators in the southern state of Karnataka submitted their resignations, boarded a private plane to Mumbai, and holed up in a five-star hotel. Party leaders attempting to dissuade them from switching allegiance to the BJP were made to wait outside the hotel in the rain. The police later escorted one of the men, who had flown in from Karnataka, back to the airport, saying, “They are frightened of you. We cannot allow you to [remain].”

Several more legislators in the state government then resigned, forcing a vote of no-confidence on July 22 that ended with the BJP emerging as the largest party in the state. On the floor of the house, a legislator alleged that he had been offered 5 crore rupees (approximately $725,000) by the BJP to switch party allegiance, a relatively small amount that shows just how cheaply some politicians can be bought. Others had allegedly been offered as much as 50 crore rupees (more than $7 million).

Horse-trading is a familiar component of Indian politics, with some representatives switching parties repeatedly throughout their careers out of self-interest. But the successful attempt to bring down a state government, so soon after winning an absolute majority in Parliament, suggests that Modi cannot abide even the hint of an opposition. With Karnataka in their grasp, the BJP controls sixteen states, while the INC has been reduced to governing just four out of India’s twenty-nine states.

If the allegations of bribery are true, it will reveal the existence of a political class without the moral authority to govern. In the western state of Goa, ten out of fifteen INC legislators also resigned from the party, immediately joining the BJP. The majority of defecting legislators were Christians who were elected to represent the interests of their constituents at a time when incidents of religious hate crime have soared. As much as 90 percent of such crimes since 2009 have occurred since Modi became prime minister. Voted into power as members of a secular party, these people will now promote the agenda of a governing party that seeks to make India a Hindu nation.

*

One institution that might have been expected to hold Modi to account is the news media. But journalists critical of Modi face torrents of abuse online, including rape and death threats; they have been manhandled, arrested, and detained, and Modi himself has called them “prostitutes.” These attacks increased in the run-up to the elections, declared Reporters Without Borders. “Hate campaigns against journalists, including incitement to murder, are common on social networks and are fed by troll armies linked to the nationalist right,” the group said.

Last July, one of India’s most widely respected news anchors started to receive complaints from all over the country about his show being blacked out. The host of Master Stroke, Punya Prasun Bajpai, had been highly critical of Modi. His prime-time show, for instance, had embarrassed the government by revealing how a broadcast video-conference between Modi and farmers that was meant to convey growing prosperity in the rural hinterland had been faked. The farmers had said that their incomes had doubled since Modi had come to power. But suspecting otherwise, Bajpai sent reporters to verify this information—and they learned that the farmers were following a script they’d been given.

Bajpai was warned by his boss that news channels critical of Modi “even just 10 percent of the time” were being blacklisted by the BJP. Party spokespersons refused them interviews. After his boss ordered Bajpai to stop using Modi’s name or even his image in any report that was critical of the government, Bajpai quit. The wider media drew the obvious conclusions.

Since Modi’s victory, the majority of journalists have focused on the INC’s problems, rather than the BJP, even though it is no longer a viable opposition. Long-dead Congress leaders, such as Nehru, are regularly criticized. Meanwhile, clearly false reports, such as how the Modi government is “working for (the) welfare of minorities,” are presented as news. The fawning from some quarters is almost a parody of journalism. One weekly national magazine, Open, has featured Modi on the cover ten times, just this year. In his letter to readers, the editor has described the prime minister as the man who “incorporates the entire universe in his own life story.”

Even the judiciary’s independence is in question. Modi’s government has meddled with judicial appointments, instating friendly judges, and rejecting appointments of those who have previously ruled against the party. Then, last January, four Supreme Court justices called an unprecedented news conference. “There are many things which are less than desirable which have happened in the last few months,” one said. “All four of us are convinced,” he continued, “that unless this institution is preserved and it maintains its equanimity, democracy will not survive in this country.”

A compromised media and a judiciary under attack, as well as open meddling in the Election Commission, even at the Reserve Bank and in the military, are all signs of institutional erosion. But Modi’s latest assault is on truth itself. According to his own Ministry of Statistics, Modi’s government has been manipulating economic data to show progress, even as it retrospectively downgrades growth figures under the last Congress-led government. The National Crimes Records Bureau has, for the first time in its history, failed to publish its main reports on crime and prison statistics —a vital resource not only for the public, nonprofit organizations, and journalists, but also for politicians trying to make the government accountable. And a proposed legislation to the popular Right to Information Act will make it more difficult than ever for ordinary citizens to learn the truth.

Meanwhile, the personal information of private citizens is fully accessible to the government through Aadhar, an identification system that has made it virtually compulsory for people to provide biometric data in order to access a raft of services, such as welfare benefits and insurance payouts. More than a billion Indians—almost the entire population, in fact—have enrolled. One prominent economist described the system as “Big Data meets Big Brother.” Knowledge is power, and from now on in India, the information will flow only one way.

There is resistance to Modi. It can be seen in the work of lawyers who refuse to back down despite being harassed as “anti-national,” and among the activists who mobilize to help victims of lynch mobs. It is visible, too, in a number of independent news and fact-checking websites that have mushroomed in response to Modi’s false narratives and the supine corporate media. And it is found in the public protests of private citizens who continue to reject his vision of a Hindu India. As though in response, the Modi government this month passed a legal amendment in the lower house of Parliament that will empower the state to designate individuals, not just organizations, as “terrorists”—potentially permitting the government to criminalize a person it chooses to accuse of “promoting terrorism.”

The rot may have set in decades ago, but it has taken Modi only five years to dismantle the idea of India as democratic and secular. The opposition movement is fragmentary and local. It will surely have to be widespread and united—with an equally potent alternate vision of India—if Modi is ever to be defeated.