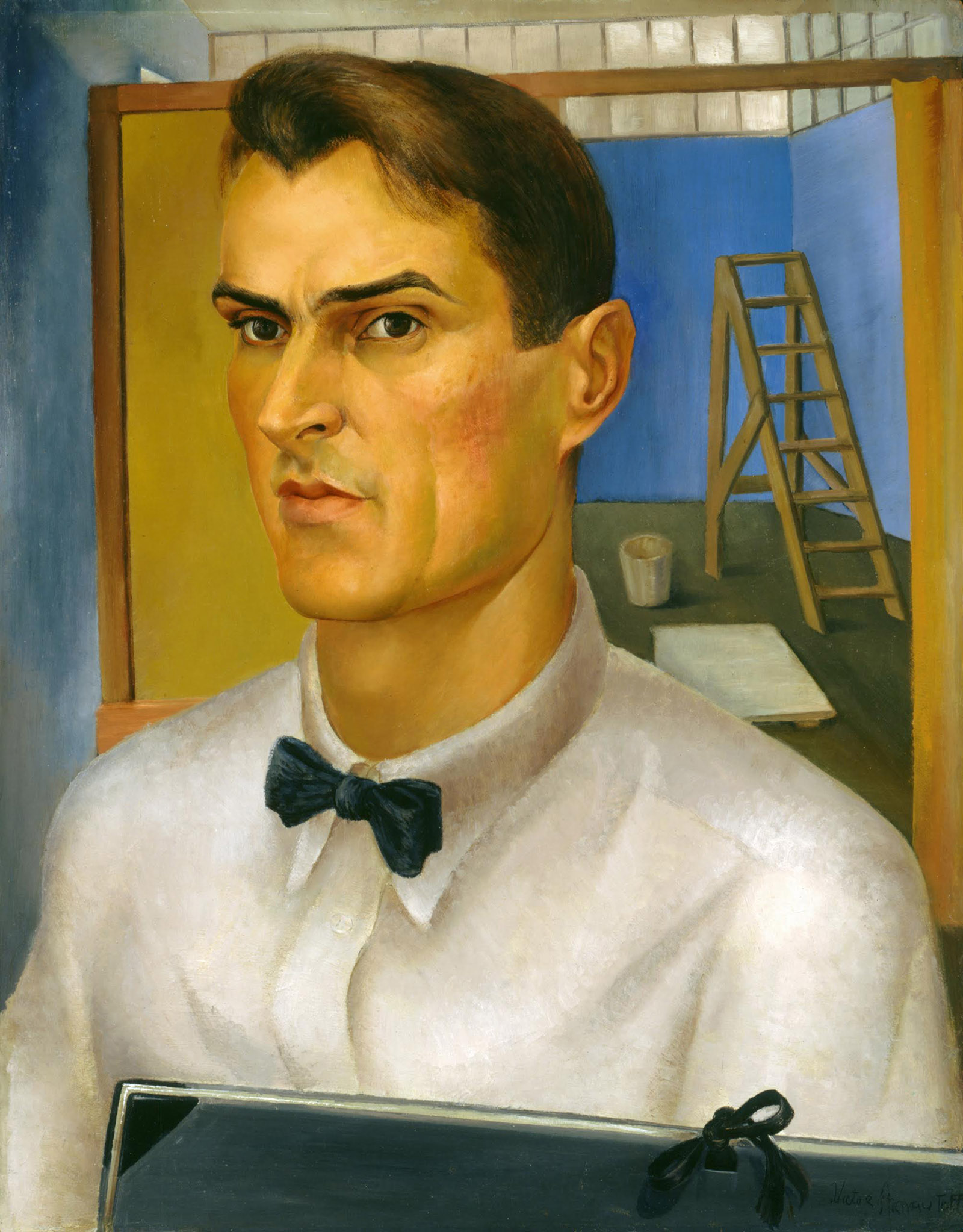

On June 25, the Board of Education for the City of San Francisco voted to paint over white a vibrantly-hued 1,600-foot cycle of frescoes, The Life of George Washington. Completed in 1936 in a social-realist style by the Russian-born Victor Arnautoff (1896–1979), who was a Communist, the paintings adorn the stairs and 32nd Avenue lobby entrance of George Washington High School (GWHS), attended by some two thousand students in the city’s Richmond neighborhood.

The school board acted in accord with demands from two First Nation activists and their supporters, who for some months had contended that their adolescent children experienced “generational trauma” because the art works depicted several black slaves and a dead Native American. Adopting the hashtag #paintitdown, the anti-mural groups insisted that the Board of Education accommodate its desire for a safe space by destroying them. The events set off a furor, still in progress, pitting concerns about history, censorship, and education against demands for respect, social justice, and redress.

The school board’s drastic stance was a travesty, given the murals’ iconography and history. Sponsored under federal auspices, through the Fine Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration, the murals were one of seven ambitious New Deal-era art commissions for GWHS: an extraordinary number that attested to that campus’s unique standing as a showcase for municipal art, architecture, landscape design, and public education. In a detailed report of October 2017, the San Francisco Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) highlighted this fact, and called for the fresco cycle to receive landmark designation. In a move of political expediency and cowardice, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors tabled HPC’s recommendation (much to HPC’s chagrin), pending the outcome of the school board’s vote.

Befitting the work of an artist who had previously collaborated with the Mexican Marxist painter Diego Rivera, Arnautoff’s murals were provocative in his own time, for reasons with which the #paintitdown contingent might perhaps have identified. Although they depict the life of the school’s namesake, the “formation of personality” and his “personality in action,” as the artist put it, Arnautoff’s murals were hardly celebrations of the slave-holding president. “It is not the prissy, Parson Weemish Washington of the cherry tree,” remarked the San Francisco Chronicle’s critic Albert Frankenstein of The Life of George Washington in 1936. Indeed not.

“As I see it,” wrote Arnautoff in 1935, “the artist is a critic of society.” As the Arnautoff biographer Robert Cherny has shown, that critical stance underpinned The Life of George Washington and much of the artist’s public work. In that sense, his approach was akin to a number of other radical artists of the 1930s, such as Rockwell Kent, who embedded occasional subtle but provocative left-wing social messages into their murals. This method differed from those of more moderate New Deal muralists, whose treatment of their subjects tended to be straightforwardly affirmative and middle of the road.

Regarding particular works, Arnautoff never stated his intentions outright. His approach was understated, even ironic in tone, but it was consistent with his broader outlook as a Communist in 1935–1936 who sympathized with African-Americans, Native Americans, and working people—an outlook made manifest in his Life of George Washington. Subversively for its time, the high school fresco series portrayed Washington himself and his legacy to the nation as complicit with the institution of slavery and acts of genocide against Native Americans.

In Westward Vision, for example, the tableau deemed most offensive by the #paintitdown advocates, Washington, in the company of Benjamin Franklin and others (unidentified by the artist, but it has been suggested: James Madison, to Franklin’s left, and Thomas Jefferson, to his right), points to a map and gestures forcefully to a grisaille apparition of frontiersmen, presaging the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. The corpse of a Native American man lies prone beneath the pioneers. Native Americans are depicted throughout as war-painted adversaries, some threateningly wielding rifles. African Americans are rendered as slaves, tending to Washington’s horses and laboring in the fields of Mount Vernon. Arnautoff’s iconography of race was not atypical within the history of American art; one can find images like them in the United States Capitol. But for a Communist artist to get away with critiquing, as part of a federal cultural program, the very “Father of our Country” in whose honor GWHS had been named, was out of the ordinary.

The #paintitdown advocates, however, did not see the portrayals of Washington as indictments of the myth. They refuted assertions about the murals’ pedagogical significance, insisting that the feelings of some members of a long-oppressed minority group trumped claims by academic experts, whose views they regarded as racist. According to one of the most outspoken activists, GWHS parent Amy Anderson of the Ahkaamaymowin group of Métis, The Life of George Washington automatically represented a colonialist perspective because it was painted by a white man; therefore, the frescoes validated white supremacy.

The progressive school board accepted this argument virtually without question. No matter that its members apparently misconstrued Arnautoff’s intent, that the works had educational potential, or that a majority of GWHS teachers and students opposed destroying them. The board insisted that it was acting in solidarity with people whose voices were too often not heard.

Indeed, the June 25 vote could have been predicted, given events leading up to it. In late 2018, after entertaining a proposal that the school’s name be changed, San Francisco school board president Stevon Cook had convened a Reflections and Action Working Group, dominated by anti-mural people, to make recommendations to the board. Historians and other experts on New Deal art, such as the architectural historian Gray Brechin, were glaringly excluded from the panel, which on February 28 voted to recommend to the board that it paint over the mural. The lone dissenter in that poll was Lope Yap Jr., appointed because he represented the GWHS Alumni Association (as vice president). The Board of Education’s June 25 “paint-white” vote followed the Reflections and Action’s February 28 directive and steamrolled over Yap’s conflicting opinion. San Francisco school board Vice President Mark Sanchez explained the decision: “This is reparations.”

Since that June referendum, the controversy has devolved into a political circus. Infuriated by the manner in which the deliberations had played out, Yap became a leader in efforts to preserve the murals. The GWHS Alumni Association threatened to file a lawsuit against the board and to arrange for a ballot measure on the fate of the murals in November’s city-wide election. Critics from both ends of the ideological spectrum ridiculed the board’s decision.

Opponents also included the African-American artist and associate professor at the San Francisco Art Institute Dewey Crumpler. After black students in 1967–1968 protested The Life of George Washington’s depiction of slaves, the young Crumpler was recruited—and endorsed by the Black Panthers—to paint “response murals” for the school; his Multi-Ethnic Heritage: Black, Asian, Native/Latin American (1974) became an integral part of GWHS’s extraordinary collection of leftist public art, inseparable, in Crumpler’s opinion, from the message of Arnautoff’s paintings. If Arnautoff, in the sardonic style of the 1930s left, showed students how “the march of the white race from the Atlantic to the Pacific” was part and parcel of the George Washington legacy, Crumpler’s decidedly unironic vision—equally influenced by the Mexican muralists—paid tribute to the many peoples who struggled as a consequence. Through the passionate visual language of 1960s community art, his triptych, which deliberately complemented Arnautoff’s, affirmed that African Americans, Asian Americans, Latin Americans, and Native Americans, too, were central to the nation-building story beginning with George Washington.

Under fire, the board backtracked a bit. On August 13, it voted 4–3 for a second option—among two censorship alternatives entertained at the February 28 meeting—of covering the frescoes with permanent paneling. At an estimated cost of $825,000, this approach would ostensibly preserve the frescoes in a manner not possible with the paint-over measure. The solution, said Cook, would enable the board to get on with “real” school board business.

That decision placated nobody, including the #paintitdown activists. A recently-formed Coalition to Protect Public Art began pushing back, harnessing formidable media, legal, and political backing to pressure the school board to rescind its vote. Former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown and the Pulitzer prize-winning author Alice Walker, whose daughter attended GWHS, along with Crumpler and the president of the NAACP’s San Francisco chapter, Rev. Amos Brown, agreed that the Arnautoff’s murals contained a critique of Manifest Destiny ideas and all pointed to the educational necessity of exposing students to disquieting historical material. They argued vociferously for keeping the murals visible, to engage students in critical thinking about the controversial issues they raise. The actor and GWHS alumnus Danny Glover equated the board’s action with book burning. Senator Dianne Feinstein, Democrat of California, wrote to the board protesting its proposed action. Socialists raged at the decision during a panel discussion at Berkeley’s Revolution Books, even as conservatives exploited the situation to discredit all manner of leftists.

Advertisement

The anti-censorship crusade moved beyond the Board of Education and into the mayor’s office. San Francisco Mayor London Breed’s representative on the Board of Education, Jenny Lam, a member of the “paint-over” coalition of June, and up for reelection in November 2019, shifted over to the “merely cover over” contingent in the August 2019 vote. Lam’s move was an acknowledgment of her political vulnerability: a former tenants’ rights lawyer and artist named Bobby Coleman, who is adamantly opposed to the frescoes’ concealment, is challenging Lam for her board seat. He has been endorsed by Matt Gonzalez, chief attorney for the city’s Public Defender’s office. A former president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and one of the city’s most powerful Democrats, Gonzalez wrote an op-ed for the San Francisco Examiner defending the Arnautoff murals. By endorsing Coleman, he gave Lam a clear signal: that her vote on The Life of George Washington might well cost her her job (and, by inference, that the policies of the Breed administration were under new scrutiny). Whether any of this pressure will succeed in reversing the board’s original cover-up verdict is still an open question, but the stakes in the political game have been raised.

What can be said is that these disputes have raised important and pressing questions about race, representation, pedagogy, power, knowledge, and the meaning of public art. Who decides what is legitimate civic art in 2020, especially when it’s intended for minors? Should personal feelings take priority over historical and educational group interests? How should we weigh competing claims based on different periods’ historical perspectives? When is it permissible or advisable to use censorship?

The Arnautoff mural discord is paradigmatic of our divisive times. For the defenders of the murals, myself included, it embodies “cancel culture” writ large, to the point of caricature. In the case of public art, that iconoclastic impulse dictates removal of traditional forms whose subject matter or motivating intent fail to measure up to today’s standards. But there are other, more productive ways of making sense of Arnautoff’s pictures. Misunderstandings arise from the presupposition that older public art works must be celebrations of their subjects or be produced by approved people. The contention that the Arnautoff murals’ depiction of African-American and Native-American subjects is demeaning and trauma-inducing and that this should be the main criterion for judging their worth have obscured other aspects of the artistic enterprise, including the Crumpler responses, that complicate and enrich their significance, and that offer a way around today’s toxic divide. These meanings emerge through investigation of specific projects as processes, embedded in a historical continuum. Truly making sense of The Life of George Washington, for example, should involve analysis of the full patronage history of the murals, given both its New Deal heritage and its status as a municipal initiative, as well as of the paintings’ subsequent reception, from 1936 through the late 1960s to this moment’s political jockeying.

The significance of traditional murals and monuments lies not merely in their status as static objects and images, nor merely as paragons of virtue or villainy, but also as articulations of biography and urban social history. Public art is a dynamic political process that unfolds over time and involves specific people, groups, and circumstances. It is a nexus of interactions, negotiations, and powerplays, past and present. Today’s Arnautoff mural dramas have taken on a life of their own, but they are part and parcel of the paintings’ meaning as a material part of San Francisco’s ongoing history. This more catholic perspective on civic art as process and municipal history can offer a constructive way to understand these projects and the controversies, and get beyond the destructive polarities of entrenched positions.

Educators could engage students in a fruitful conversation about how these circumstances came about. They could explore together the contrast between the left political positions Arnautoff held and the racist views held by many of the period, and how this tension is inscribed in his art. Teachers might also work to help students learn to distinguish between reacting subjectively to art work and exploring dispassionately the complicated historical reasons for what it depicts. The murals provide rich opportunities for such discussion, but those lessons will be impossible if the paintings are invisible.