One afternoon in 1961, Hugh Edwards, the associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, said to me, “Go downstairs and look at those pictures.” They were photographs by Robert Frank, his first solo show in America. Hung on both sides of a long, narrow basement gallery, the prints and pictures were dark, the horizon often tilted. The few people in them that looked at the camera had a wondering, suspicious expression. The photographer Aaron Siskind, based at the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, criticized Hugh for showing prints at the Art Institute that had dust marks on them. “With pictures like that, who cares about the prints?” was Hugh’s answer.

The picture of Frank’s that I liked the most was shot in a park in Michigan—a B&W photo of haunting, mysterious beauty, a landscape with a woman holding a child in the foreground, an African American in uniform at the side, and the sparkling expanse of a lake in the background. Hugh told me to go to Wittenborn and Company, a book store on Madison Avenue in New York City, where I bought the last two copies they had of The Americans: the original French Edition, in which the publisher Robert Delpire had placed a text across from each picture, and the first American Grove Press edition, which had only Jack Kerouac’s introduction as text. Half of that gravure copy had been bound upside down. Each book cost $7.

Last year, I rang the buzzer of Robert Frank and his second wife June Leaf’s house on Bleecker Street in Manhattan, and climbed up the two narrow, worn flights of stairs leading to the room that he used as a bedroom, kitchen, and living room. Robert, then ninety-three, had been lying there in the dark. Rising as I came in, he sat in a heavy bathrobe at his small kitchen table. As I sat across from him and we talked, I noticed his feet beneath the table were bare. He asked about my children and my health. I told him he looked good—he had more hair than I did. I had a camera and he motioned with his head that I shouldn’t use it.

I thanked him for taking me in and letting me live in his apartment when I was a kid. After my work in Texas, when I returned to New York City at twenty-seven and had no place to live, Robert let me move into his family’s apartment on West 86th Street. I lived there for six months. “I could never be so generous to anyone,” I said. When I rose to say goodbye, he said, “Thank you for visiting me.” It was such a nice visit that I told myself I would bring my youngest daughter Rebecca to meet him when she was in the city that summer. But Robert and June were at his home in Mabou, Nova Scotia, and so I never saw him again.

Many years ago, when I lived in the Hudson Valley, I brought a twenty-two-inch striped bass to the same apartment to give to Robert and June. I had taken the bass, which I’d caught in the Hudson, folded it in half, and crammed it into a small cooler. I filled it with ice and carried it into town on the Metro North train. I hardly ever spoke with Robert then, and the fish was really just an excuse to see him. The next day the phone rang in my Ulster County home. “I just wanted to thank you for bringing dat fish.” He still had a Swiss accent. “I was really impressed by how you brought it down here. Dat was really something,” he said, and hung up. It was the only time Robert ever called me. I was in heaven.

It had been years since I’d lived with him and we were no longer close, but I would still try to say hello, or send him a letter now and then. Once, I sent him Jim Harrison’s novel The Road Home and when I saw him, he said, “I already had it.” It was obvious I was trying to renew our friendship. During one visit, he asked me how old I was. I broke out laughing: I was sixty-eight. He said, “You know, it can’t be now like it used to be.” He meant he had changed. And he meant I had changed, too. I wasn’t twenty-seven anymore. You cannot return to the past.

Three years ago, the co-curator of my retrospective, Julian Cox, wanted to include one of Robert’s pictures in the show catalogue—the one he took down the center stripe of a highway—and place it next to a picture I took in Mississippi, also standing in the middle of the road. Julian couldn’t get permission, so I called Robert, interrupting his lunch. I explained that it was good to have the picture in the book, it was to show his influence on me. But he wasn’t interested. “Why the fuck would I want to have one of my pictures in your book?” he said, pretty much ending the conversation. He had a very special way of saying “fuck.” It sounded more like “quack.” There is something endearing about being cursed by a real Beatnik.

Advertisement

Robert Frank was a very private person. I knew he considered any violation of his privacy a personal betrayal, so I was surprised when the curator Philip Brookman, whom I knew from the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, called me one day to say he wanted to interview me for a film he was making on Robert. I refused, saying I wouldn’t be in it unless he got a note from Robert saying it was okay to talk about him. Later, when I saw the film on television, I regretted not being a part of it. One day on Bleecker Street, I ran into Robert and said I was sorry I hadn’t been in his film. It was Yom Kippur and Robert said, “This is a good day to say you are sorry.”

*

In 1967, I was part of a “happening” with the Park Place Artists in Judson Memorial Church at Washington Square in New York. Standing up in the balcony with the sculptor Mark di Suvero, we looked down at a crowd of people milling about the lobby as the event ended. In the middle was a short man with dark curly hair and a taller, good-looking woman. “That’s Robert Frank and Mary Frank,” said Mark, pointing down at them. “Would you like to meet him?”

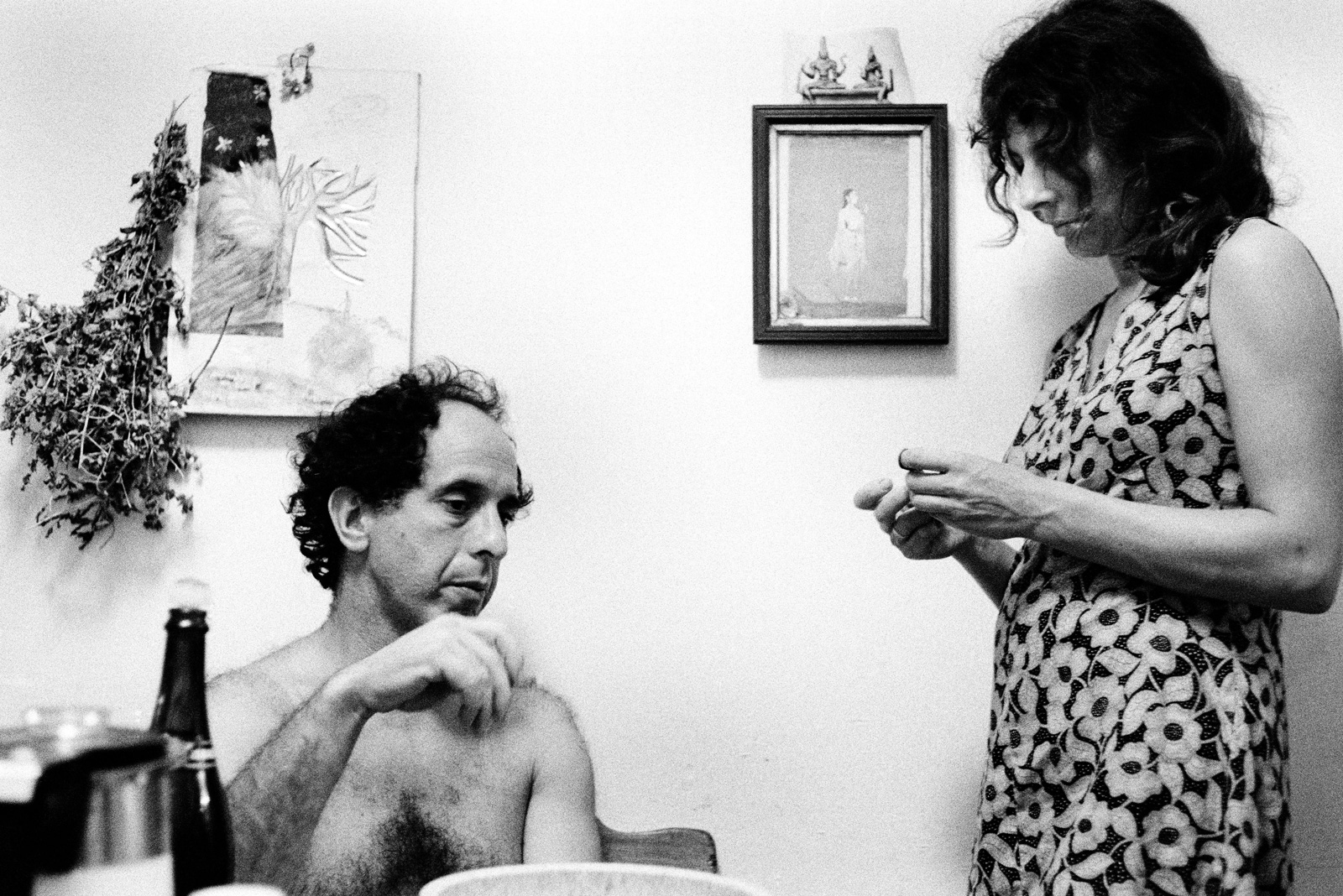

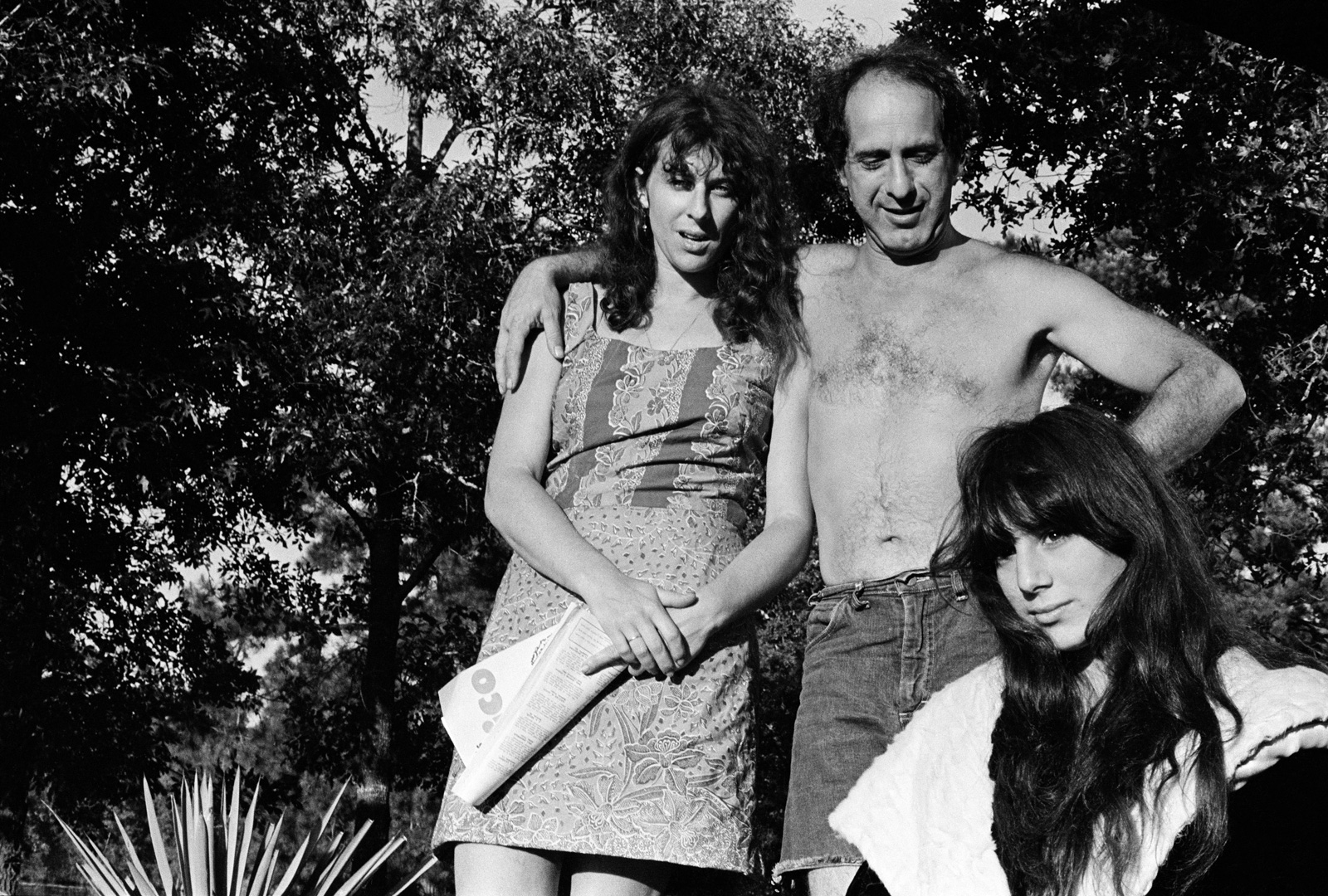

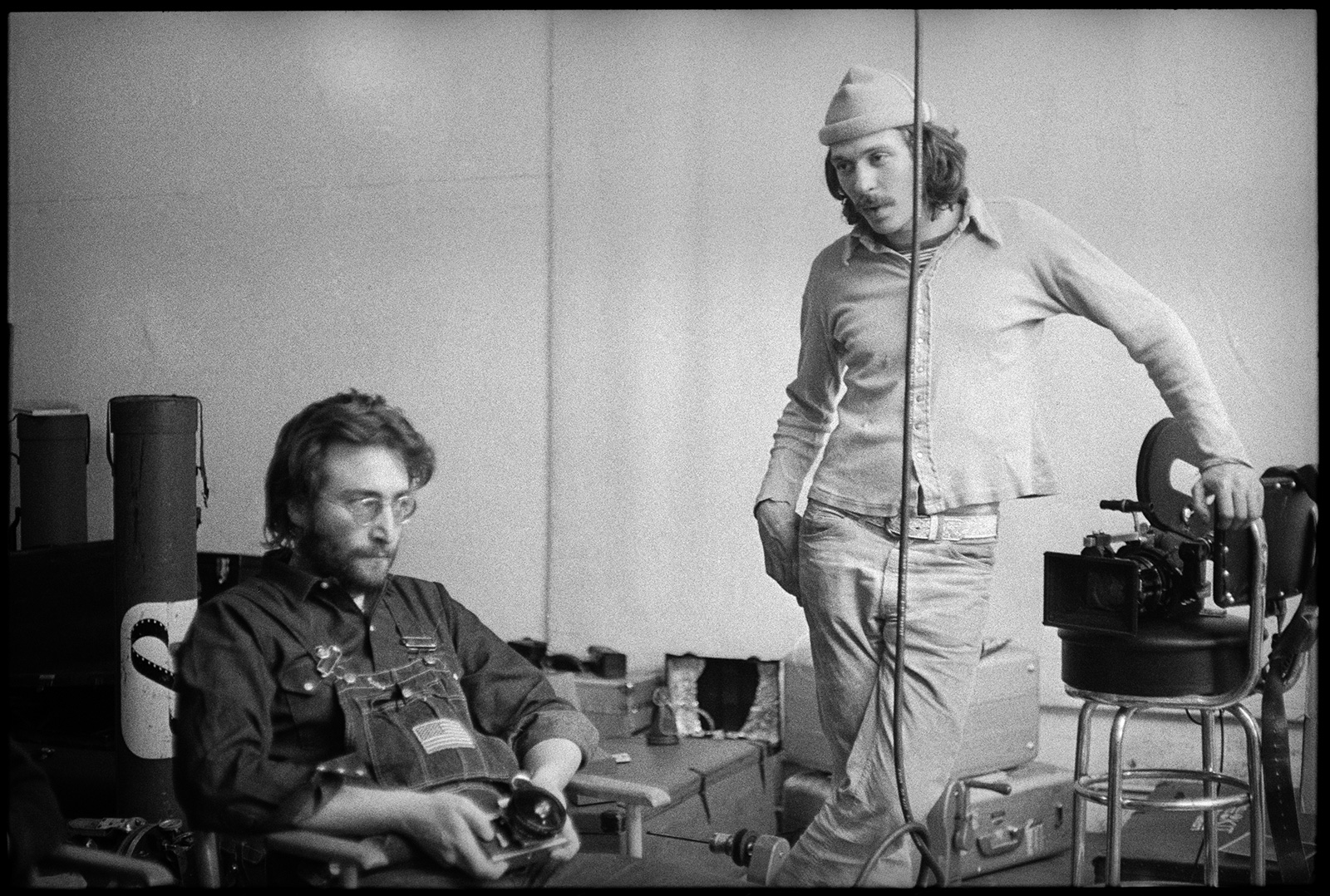

It was the beginning of a friendship that would last about two years. In early 1969, I moved into Robert and Mary’s apartment on West 86th Street. Their two children were off at school and I lived in Pablo’s room. I was twenty-seven; Robert was forty-four. In return for a place to stay, I helped Robert make his films, mostly doing the audio with a large Nagra IV and a Sennheiser shotgun mike. I had finished my work making pictures in Texas prisons, and had shot my own first film in Houston. I brought all the footage to New York, where I planned to edit it. I also brought with me a 16mm Éclair camera that belonged to the Media Center in Houston, a very hot item among filmmakers. I told the Center I had to shoot something in New York. This wasn’t really true, but I knew Robert would use the camera. With me sleeping in his apartment, he shot three films: Conversations in Vermont, About Me: A Musical, and Life-raft Earth. We smoked pot almost every evening.

By the early 1960s, his book The Americans was out of print, but the work was legendary among the small arts community that mostly lived in Lower Manhattan’s lofts. It was finally reprinted by Aperture in 1969, with Sid Rappaport using his “stone tone” (duotone) process of running the sheets through the press twice with two types of black ink. In the same year, on the same presses, Sid printed my second book, The Destruction of Lower Manhattan.

Bruce Davidson, who was with Magnum Photos, lived in the same large apartment complex as the Franks on the Upper West Side. Robert had been rejected by Magnum much earlier, he claimed, “Because I had egg on my shirt.” I was living at Robert’s and using Bruce’s darkroom to make prints for the Lower Manhattan book and for my prison book. Money was tight and Robert and I were sharing the rental for a Moviola editing machine, all of $25 a month. I would use it in the daytime and Robert would use it at night. On the floor of the same room as the Moviola sat their small black-and-white television set, which had a wire clothes hanger for an antenna, to which Robert would attach aluminum foil for fine tuning.

After returning the Éclair to the Media Center in Houston, we purchased the same camera together. His father brought it to us from Switzerland so we could avoid the sales tax on purchases by foreigners. The Angénieux lens was purchased by Magnum’s Marc Riboud in Paris, which I picked up from him in a midtown hotel. The total cost was about $5,000, which Robert and I split. As he filmed music I followed him with the mike. He moved like a dancer.

Advertisement

Later, we traveled together to Texas, where I persuaded him to accompany me inside the Texas prison with our new 16mm camera, something I never would have done for any other filmmaker. I just wanted to show off that I could do it.

The night of the moon landing we were filming in Tompkins Square in New York. Some kid came up to me and wanted $5 for a stolen MasterCard. It was common then to steal them from people’s mailboxes. I negotiated him down to $2 and then proudly showed it to Robert. The name on the card was “Sweeney.” The next morning, he stopped his station wagon in front of a camera store uptown on Madison Avenue, and as a test I went in to buy some rolls of 35mm color film. I told the clerk I’d left my ID in the car. I kept looking at the door, thinking I would run out and jump into the car for a quick getaway if the card wasn’t approved. But the payment went through. Then we drove downtown. I walked in and out of stores and bought everything from stuffed elephants for the kids to clothes for Mary, just filling up the back of the car while Robert sat in the front. I wanted to buy tickets to Albuquerque, where we had been filming, but Robert wouldn’t allow that, so we had a lobster dinner instead. Then he made me toss the card into a garbage can on the corner.

That August, 1969, I spent the three days of the Woodstock music festival in Bruce’s darkroom listening to the news of traffic jams ten miles long on the New York State Thruway, glad I wasn’t there. When it was over, Robert and I drove out to JFK to get on a chartered American Airlines flight to Albuquerque. Practically every seat was occupied by hippies from the New Mexico Hog Farm who had been brought in to “police” the upstate concert. After hours on the tarmac, the boys and girls started playing bongo drums and a man came down the aisle with a wineskin and small white cups offering “electric Kool-Aid” to everyone. Robert became bored enough to borrow my Leica to make some pictures of the kids in their seats. On my aging contacts, in yellow marker, I have a few pictures bracketed with a note, “Robert took these.”

In exchange for an eye exam by my father, Dr. Ernst F. Lyon, Sid Rapport, the man who had re-printed The Americans, made a few boxes of stationery handsomely designed with dark green fonts on heavy ivory paper: “Sweeney Films: Robert Frank and Danny Lyon. If It Moves We Film It.” We were going to make lots of money—but, of course, we never did anything but print the stationery, which had a long column of absurd rates running down the side, such as triple-processing charges because “we wash our negatives in pure rainwater.”

*

Mary Frank told me that when she and Robert were younger, she used to trade her sculptures with the butcher for meat. Robert never had any money. When Harold Hayes, the editor of Esquire, with whom Robert played tennis, wanted to do a profile of Robert and he refused, Mary got on his case. “That’s why no one knows about your films,” she said. He slammed his hand down on the table and I knew things were not well between them. Soon after, when one day he was driving the station wagon up Fifth Avenue, he stopped near 42nd Street, told me to get in the driver’s seat, and jumped out of the car. When I stared at him, he said, “What’s the matter? You never heard of anyone having an affair?” and left.

Once, at his apartment, he put on a record of Ma Rainey singing “See See Rider.” It was a single on an LP, and as soon as the track ended, he would lift the needle and play it again. He must have done this twenty times. I can never play that recording without thinking of him, and sometimes do the same thing, playing it over and over. “I’m goin’ away babe, but I sure don’t wanna go. / When I leave you this time you’ll never see me no more.” It is a song about an unfaithful lover.

When we filmed Life-raft Earth together in the desert in New Mexico, smoking pot and looking for rocks to collect, he turned to me and said, “I envy the position you are in.” I was stunned, but realized later what he meant: I was single, I was free, I did pretty much whatever I wanted when I woke up in the morning.

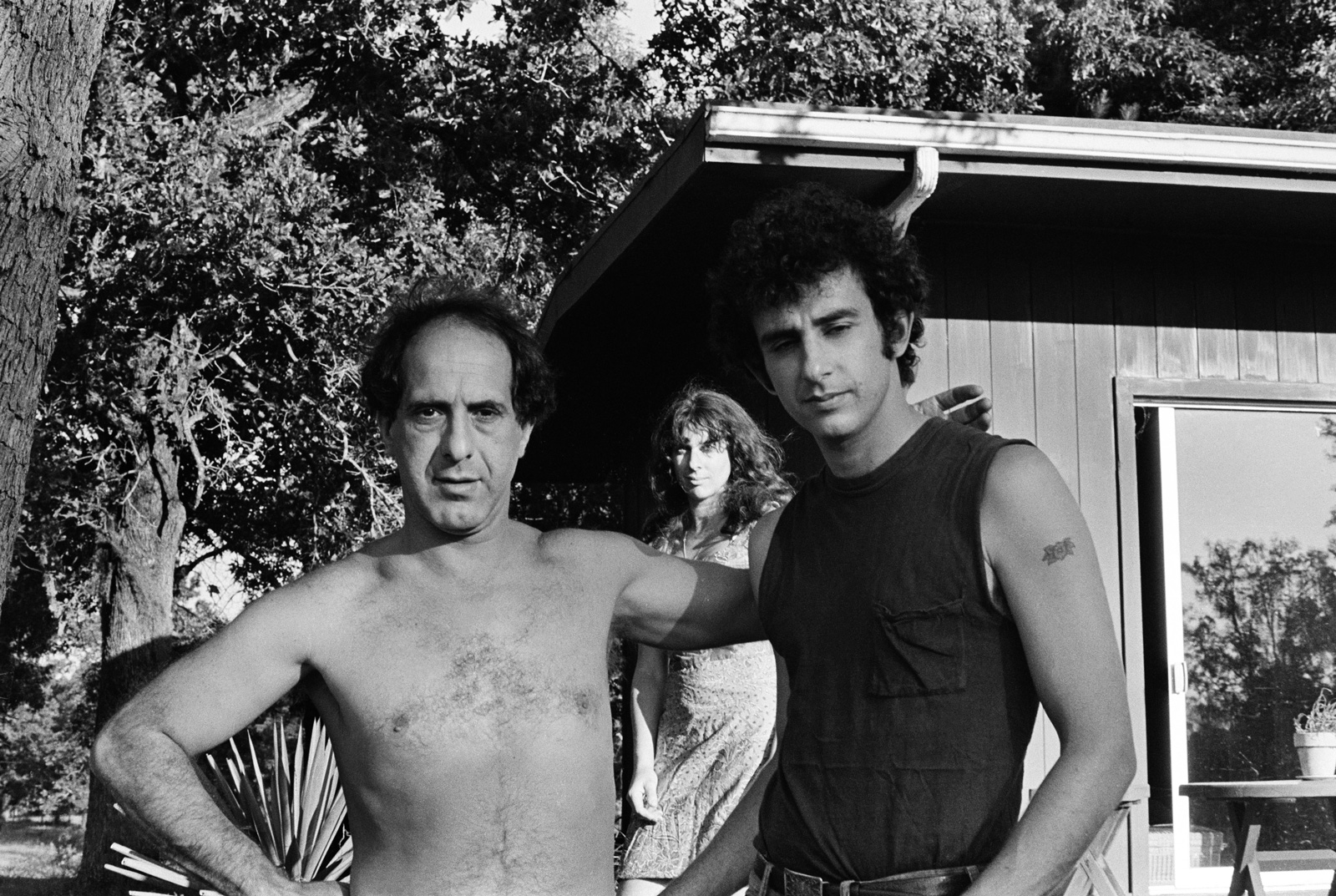

One day in 1970, when I came back from New Mexico, there, standing in the Franks’ living room, was a tall, handsome, younger man with long hair and tight, bell-bottom corduroys. I had met many other people in that living room: Sam Shepard, who had helped Robert with a film script for his only 35mm feature, Me and My Brother, which was playing nearby at the New Yorker Cinema; Michael J. Pollard, the actor who played the mechanic in Bonnie and Clyde; and, once, the photographer Lee Friedlander, the only time I ever met him. But this young man, Danny Seymour, was different. Robert introduced him as the best cinematographer in New York. When Robert had a job in California to film Peter Fonda, he took the camera we owned together and took Seymour instead of me to take the sound, without even bothering to tell me about it.

After that, I told him one of us should buy the camera from the other, that Sweeney Films was over. “You take it,” he said. “It’s obsolete, anyway.” About ten years later, when I lived on Chrystie Street, the filmmaker and writer Gary Leon Hill, a good friend, came to ask if Robert could borrow my camera. Of course, he could. Gary returned it a few days later and said, “Robert thanks you.” Then Gary said, “I think I’m being weaned.” He, too, was about to be replaced by another young filmmaker-photographer. Someone to help Robert. Someone to watch him. Someone to just be around him.

Danny Seymour, who had a trust, did more than take sound for Robert. He gave Robert the down-payment on a place in Nova Scotia, where Robert moved in 1970. I left New York that same year, for New Mexico. I moved into an adobe house without a phone in a village that had fewer people than you see when you walk down 86th Street to buy a newspaper. I was leaving New York, drugs, Robert, and all of it behind. Seymour bought a boat and sailed it around the Caribbean, in what was then called the Golden Triangle. He was murdered there. There is another line from “See See Rider”: “My home’s on the water and I don’t like no land at all…” Robert Frank spent his last days on earth looking at the ocean from his house in Canada, the house that Danny Seymour helped him buy.

For all artists, there is a difference between the person and their work. The man I lived with was the person. And that is who I want to remember. He brought integrity to an art riddled with compromise. It is the nature of photography to preserve the past. I never filmed Robert, I only made photographs of him. Then, a few years ago, Nancy and I were riding down Bleecker one afternoon and I had a GoPro with me, the new miniature digital video camera. Robert and June were sitting in the sun outside their place. We passed the camera around. I filmed him and he filmed me. When Nancy and I were leaving, he looked up at me and said, with great feeling, “It’s good to see you again.”