In America’s bloody history of racial violence, the little-known Elaine Massacre in Phillips County, Arkansas, which took place in October 1919, a century ago this week, may rank as the deadliest. The reasons why the event has remained shrouded and obscure, despite a shocking toll of bloodshed inflicted on the African-American inhabitants of Phillips County, speak to a legacy of white supremacy in the US and ruthless suppression of labor activism that disfigures American society to this day.

Phillips County, located deep in the Arkansas Delta, was largely rural and three-quarters African-American; in the small town of Elaine, there were ten times as many black residents as white. The African Americans of Phillips County, like those throughout the South, were subjected to segregation and disenfranchisement, those twin pillars of white supremacy. But the black sharecroppers and tenant farmers there were also the victims of a particularly harsh form of repression known as “debt peonage.” Under this system, they were loaned money or rented land by plantation owners; they were then forced to sell their crops to the owners at below-market rates and to purchase their food and other supplies from over-priced plantation stores, trapping them in a cycle of perpetual debt, with the owners keeping—and often doctoring—the accounts.

In the spring of 1919, a group of Phillips County African-American sharecroppers and tenant farmers, many of them veterans who had recently returned from service overseas in World War I, decided to challenge this system by joining a union called the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA), which had been founded the year before by army veteran Robert Lee Hill, a black tenant farmer in Winchester, Arkansas. The union’s goal was “to advance the interest of the Negro, morally and intellectually,” and its constitution ended with a proclamation: “WE BATTLE FOR THE RIGHTS OF OUR RACE; IN UNION IS STRENGTH.”

The PFHUA’s challenge to both white supremacy and the economic domination of the planter class took place amid the combustible atmosphere of the Red Scare—the post-World War I panic provoked by the Bolshevik Revolution, anarchist bombings, a huge wave of labor unrest including a general strike in Seattle, and by race riots that shook more than two dozen cities during the Red Summer. Elaine’s white population was already on edge at hearing reports that blacks were daring to organize, and further distressed by the arrival at Phillips County post offices of The Messenger, a militant black newspaper based in New York. An editorial in the paper urged sharecroppers to revolt: “Strike! Southern white capitalists know the Negro can bring down the white bourbon South to its knees by one strike at the source of production.”

So frightened was the white elite of Phillips County that one of its leading members traveled to Chicago to hire a black detective to infiltrate the union. When the detective reported back that, as Charles Young, the publisher of the Helena World, later put it, “The niggers was fixin’ to uprise”—the whites of Phillips County mobilized. They formed a local chapter of the American Legion, stored guns and ammunition in the courthouse, and secured promises that, in the event of a black insurrection, US Army troops would come to their rescue.

By late September, the atmosphere in Phillips County was incendiary. On the evening of Tuesday, September 30, a group of some 200 PFHUA members met at a church in Elaine and stationed armed men outside in case of attack. Their fears were confirmed when three men suddenly emerged from the darkness, shining a flashlight on the church. A gunfight broke out. Though some uncertainty remains as to who opened fire, several accounts reported that a white man fired first. The outcome was clear: a white security officer lay dead and a white deputy sheriff was wounded.

For the whites of Phillips County, word of the shootings confirmed that the rumored black uprising was now under way. A posse of six hundred to a thousand white men, some from Mississippi and Tennessee, were quickly organized to hunt down the killers and crush the supposed insurrection. By the next morning, the white mob was on the march; they “began to hunt Negroes,” according to a signed affidavit by a white railroad detective named Henry F. Smiddy. By day’s end, many African Americans had been slain. The white marauders cut off the ears and toes of some of the dead and dragged their bodies through the streets of Elaine.

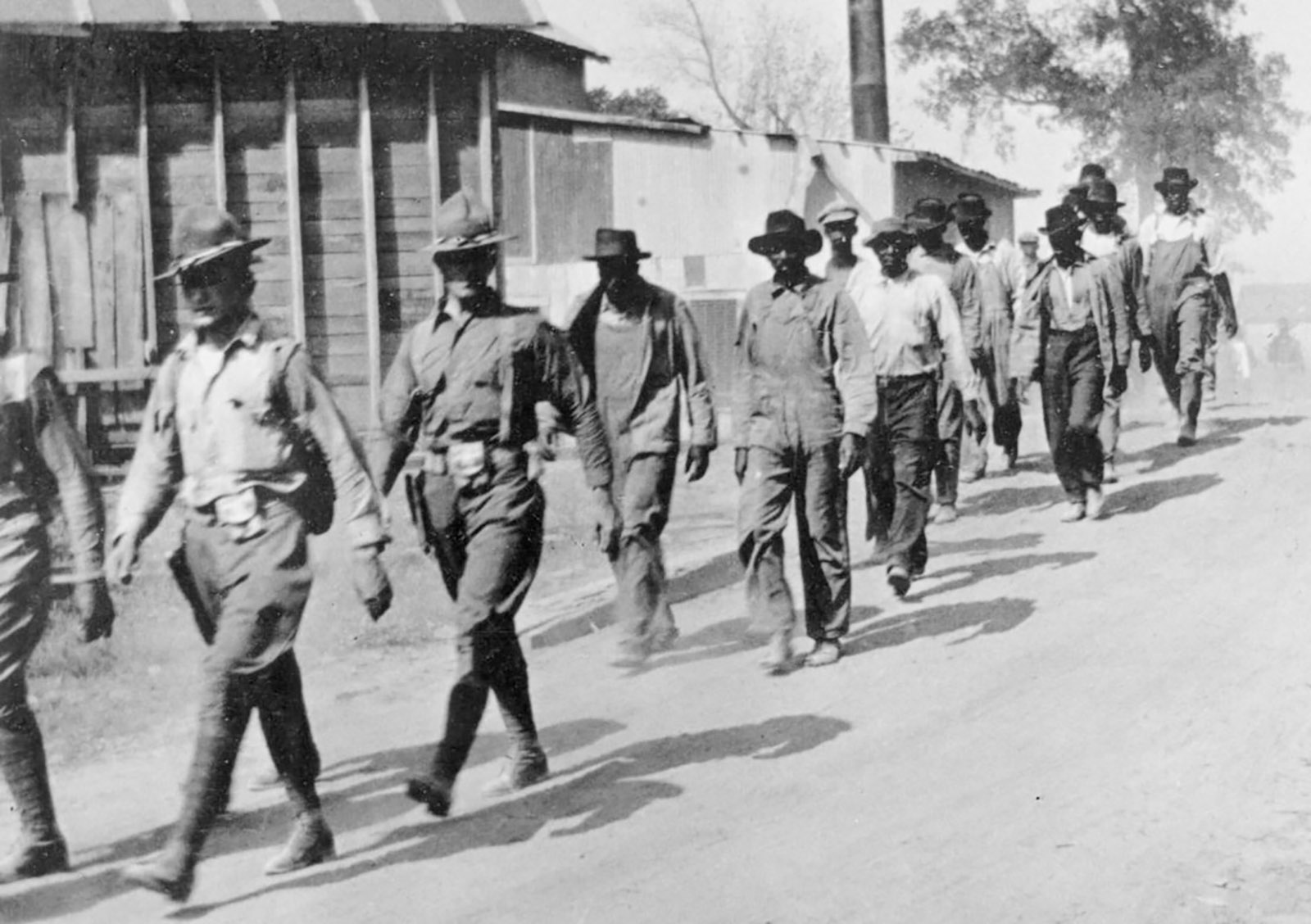

The following day, a force of about six hundred federal troops arrived in Phillips County, under the orders of Arkansas Governor Charles Brough, and with the approval of Secretary of War Newton Baker. Commanded by Colonel Isaac C. Jenks, a veteran of World War I, who years earlier had fought in the wars against Native Americans in the West, the troops brought with them equipment including twelve machine guns and “a sufficient supply of ammunition to quiet the situation no matter how serious.” Jenks, mistakenly informed by local whites that his men were facing “negro insurrectionists” who were “killing the whites whenever they ventured out to their farms,” ordered the all-white soldiers to “kill any negro who refuses to surrender immediately.”

Many African Americans, fearing for their lives, hid in the dense woods nearby. Following Jenks’s lead, officers gave the troops orders “to shoot everything that showed up.” One later bragged that “they were shooting them down like rabbits.” In one particularly barbaric instance, soldiers interrogated a captured black man; deeming him “extremely insolent,” they poured kerosene on him and set him on fire before riddling him with bullets. Meanwhile, white posses, some of them organized by the local American Legion post, continued to maraud, killing people in several locations in the countryside around Elaine.

Historians do not know exactly how many people died during the bloodshed in Phillips County, but a very conservative estimate would place the number at well over a hundred. This is consistent with the account of a secretary of a nearby black fraternal order, who reported that he paid death benefits to 103 African Americans and that members of his lodge “knew personally” seventy-three other blacks who had died during the violence. The toll, however, may have been much higher.

A respected Arkansas journalist, himself a conventional Southern racist who firmly believed that “The negro… cannot under any circumstances become the social or political equal of the white man,” reported with sadness in 1925 that more than 800 blacks had been murdered. Recently, the Equal Justice Initiative, in its 2017 report “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” estimated that over two hundred African Americans died. If this is correct, it would make the Elaine Massacre the most lethal episode of racial violence in American history, with the possible exception of the much better-known Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, a murderous rampage that burned thirty-six city blocks to the ground, left thousands of black Tulsans homeless, and took the lives of between 100 and 300 people.

Both within and beyond Arkansas, most white people accepted that the killing of African Americans was a justified response to the black “insurrection.” Even as the white mob violence was still unfolding, the Gazette, the state’s leading newspaper, announced in a headline that “NEGROES PLAN TO KILL ALL WHITES.” (“Slaughter was to begin with 21 prominent white men as the first victims,” the article declared.) The national press took a similar approach. On October 3, The New York Times reported that “trouble [was] traced to socialist agitators.” Three days later, it published a story headlined “PLANNED MASSACRE OF WHITES TODAY: Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot Among Them.”

These “confessions,” however, were extracted under torture of the alleged plotters, and decisively refuted by on-the-scene reports from two major civil rights figures, the NAACP’s Walter White and the intrepid anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells. White, an African-American whose blue eyes and white hair permitted him to pose as a white reporter, published a story in The Nation “‘Massacring Whites’ in Arkansas,” which concluded that “negro farmers had organized not to massacre, but to protest by peaceful and legal means against vicious exploitation by unscrupulous land owners and their agents.”

Wells, who had not been to the South since she was driven from Memphis, Tennessee, nearly thirty years earlier after publishing an inflammatory anti-lynching editorial in a local black newspaper, took the train down to Elaine to investigate. Her conclusion, published in May 1920 in a fifty-eight-page pamphlet, The Arkansas Race Riot, echoed White’s. The farmers who organized the PFHUA were simply “seeking through peaceful appeal to win better wage and working conditions,” and got whippings and electric shocks for the efforts—torture that led to the confessions. (For detailed accounts of the events in Elaine, see: Robert Whitaker, On the Laps of Gods, 2008; Grif Stockley, Blood in Their Eyes, 2001; Cameron McWhirter, Red Summer, 2011; and Nan Woodruff, American Congo, 2003.)

Given the magnitude of the Elaine Massacre, its absence from standard narratives in American history is striking. But unlike better-known episodes of racial violence, such as the riots in Chicago and Washington, D.C., that same year, the events in Phillips County took place in a rural backwater of the South, far from the spotlight cast by on-the-scene reporting from big-city newspapers, including important African-American publications such as The Chicago Defender and The Washington Bee. Equally important was the concerted effort of local white authorities to suppress the real story and to promulgate their counter-narrative: that a large-scale black uprising had been suppressed by prompt action befitting the circumstances.

Advertisement

In addition, the United States military was steadfast in its insistence that few people had died in Elaine. Remarkably, more than forty years after the event, The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, a respected Arkansas scholarly journal, was still disseminating the official story of the local white elite that a black insurgency had been put down with minimal violence. This confluence of elements helps to explain why an episode of this significance has been relegated to the far margins of American history.

But it is important that we remember the Elaine Massacre today, for it encapsulates two fundamental and often interconnected problems that still plague America today: the vast disparities in wealth and power between black and white, and the enormous and growing inequalities between employer and worker. Though one hundred years separate us from the episode in Elaine and legally sanctioned white supremacy ended more than a half-century ago, profound inequalities between blacks and whites, deeply rooted in the past, persist.

Today, three times more black children live in poverty than do white children (46 to 15 percent), black life expectancy is nearly four years lower than that of whites, and median black family wealth is less than one fortieth that of white families ($3,557 versus $146,984). And although labor unions today do not face the kind of mob and state violence inflicted on the PFHUA, they do meet with fierce and sophisticated opposition from employers, who deploy a variety of tactics, both legal and illegal, to block unionization. The costs of labor union weakness have been steep for blacks and whites alike: inequality today is at its highest level since the 1920s, the minimum wage in the United States ranks far behind those of its major allies among the OECD countries, and chief executives at the largest corporations make, on average, 312 times more than the typical worker (up from a factor of twenty in 1965).

History does not repeat itself, Mark Twain supposedly said, but sometimes it rhymes. Now, as then, the ideology of white supremacy provides trigger-happy men with mythical threats. Tragedies like the shootings at the Walmart in El Paso, at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, and at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston have brought back from what seemed a bygone era the jarring sounds of white supremacist violence. According to a recent study by the Anti-Defamation League, in 2018 alone, there were fifty extremist-related killings, almost all of them by right-wing extremists, with 78 percent by white supremacists.

Far from being relics of a distant past, the two forces at the heart of the Elaine Massacre—white supremacy and a huge asymmetry in power between employers and workers—are very much alive. The ghosts of Elaine haunt us still.