Looking back nearly forty years, I find that I once wrote the following words: “The nineteenth century was rich in presiding intellects… but after the publication of the first volume of Modern Painters in 1843, it had only one nervous system, and that was Ruskin’s.” At the time, I was a doctoral candidate in English literature at Princeton and a curatorial assistant at the Pierpont Morgan Library, writing catalog entries for an exhibition of the library’s British literary manuscripts. The sentence I’ve quoted represents the summit of my Ruskin knowledge for the next forty years until I reread Praeterita, his late, incomplete autobiography—“this too dimly explicit narrative,” he called it—with a student at Yale last month in this, the two hundredth year since John Ruskin was born.

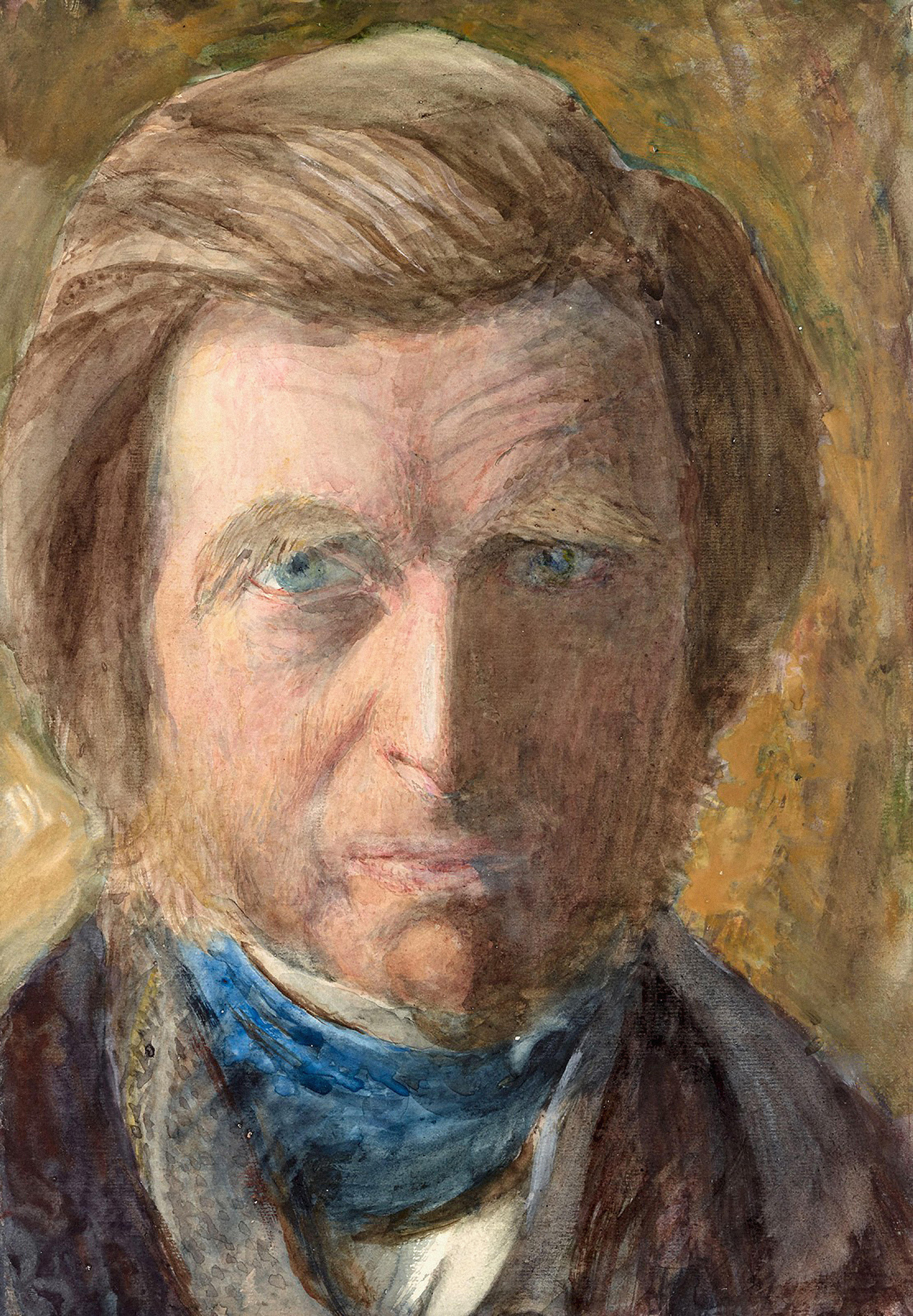

The preceding is as Ruskinian a paragraph as I ever hope to write. If you’ve read Ruskin, you know what he would have done with an opening like that—how he would have wandered, geologizing and sketching, among his memories, contemplating not the nature of time but the nature of himself and his affections, barely able to withstand the mixed joy and suffering of recollection. At age twelve, in 1831, he was writing to his father about the pleasure he took in breaking the wax seal of one of his father’s letters to him—“your very soul up at your eyes,” is how he described the feeling. Skip ahead nearly forty years in Ruskin’s life, and his soul-eyed gaze has become what he called, in 1869, “the infinite pain of seeing.” Ruskin’s eyes were blue, and he liked to emphasize their color by wearing a bright blue stock, visible in most portraits of him. Had the hue of his eyes washed away with the force of his seeing—a measure of how much he saw and how hard he looked—they would have been transparent by the time he lapsed into his final madness in 1889.

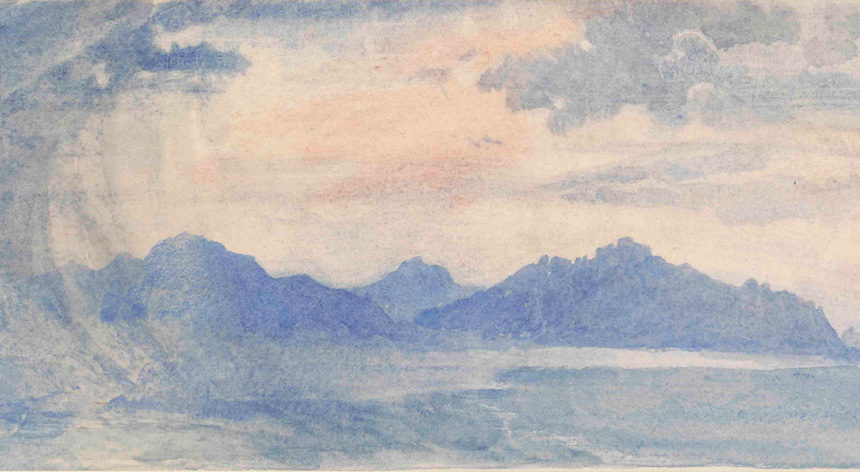

I can no longer sum up Ruskin as neatly as I did when I was working at the Morgan Library. I was a young, privateering scholar then, conducting swift, efficient raids on the legacy of one writer after another as the manuscript exhibition came together. Ruskin was a prescient critic of the industrializing world around him and an early witness of climate change, as Tim Barringer notes in Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of Ruskin, the catalog accompanying the exhibition of the same name currently showing at the Yale Center for British Art. Ruskin’s lectures called “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century”—delivered in 1884 and based on a lifetime of cloud-watching—portray the “plague-wind” that originated, he believed, in the smokestacks of industrial England. “By the plague-wind every breath of air you draw is polluted, half round the world.”

But Ruskin was also—as he announces in the first line of Praeterita—“a violent Tory of the old school.” He makes this sound like a merely literary fact—the “old school” is “Walter Scott’s… and Homer’s.” In fact, his political economy—like that of his contemporary Thomas Carlyle—was essentially feudal, vested in a far-reaching faith in inequality. His sexuality was mystifying and damnable. He was anti-modern, anti-scientific, anti-Darwin. He was anti almost anything that didn’t antecede his birth, except, perhaps, the novels of Walter Scott and the work of J.M.W. Turner. Considered all together, his beliefs are usefully described by one of Rudyard Kipling’s characters as “mixed pickles.” Ruskin is the spoiled child of the nineteenth century—stringently, evangelically spoiled, but spoiled nevertheless.

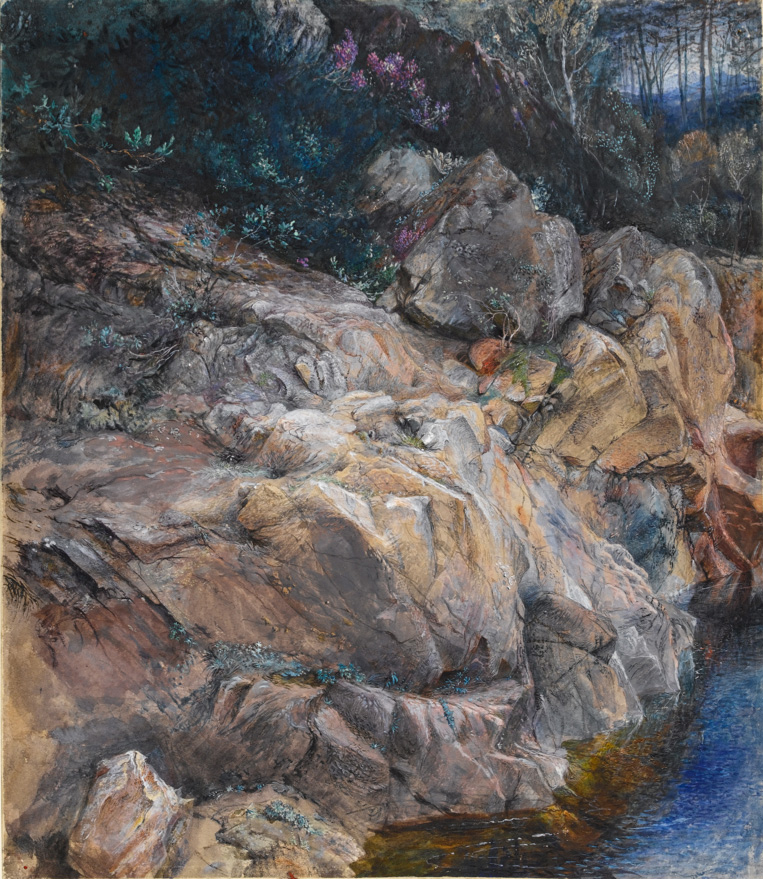

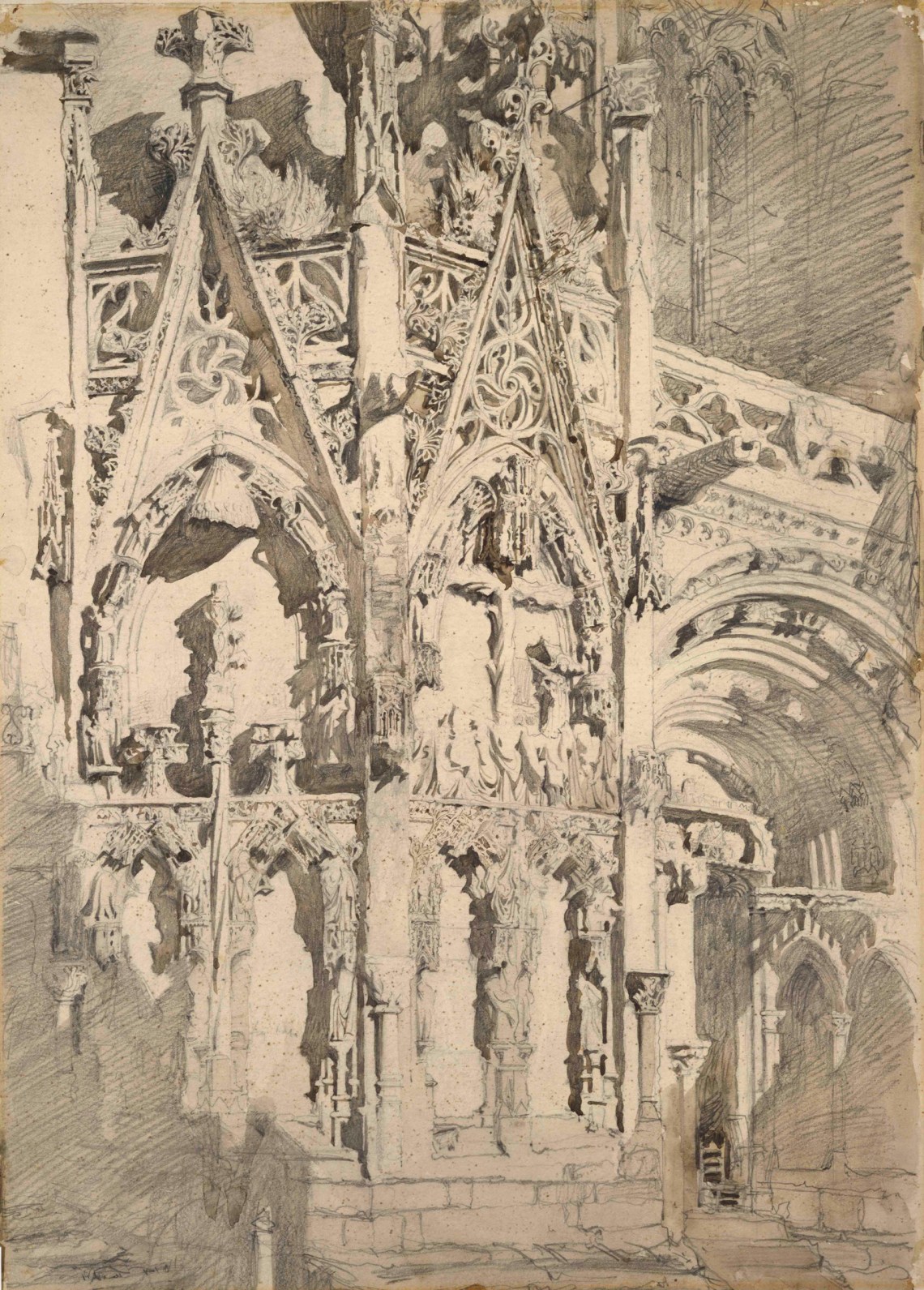

What matters is his sight, his sense of particularity, his love of detail. That is what fills Modern Painters, The Stones of Venice, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and even—strangely—Fors Clavigera, his remarkable late series of ninety-six monthly letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain. Reading Ruskin, you begin to think that he more or less lived at the tip of his pencil, in the nib of his pen, for he was always writing. His entire sensibility seems to flow into every word he inscribes. Ruskin’s manner of being in the world would call to mind the image that opens George Eliot’s Adam Bede—“With this drop of ink at the end of my pen I will show you the roomy workshop of Mr. Jonathan Burge”—except that Ruskin disliked Eliot. In Ruskin’s drop of ink, you can see his world with astonishing clarity and fascinating distortion. And you see the man himself staring back at you, balefully, as he tends to do in his self-portraits.

Advertisement

I write all of this merely to bring you to a moment in Praeterita. It is 1841, and Ruskin is twenty-two years old. He has spent the winter in Rome, for his health, and now Ruskin, papoosed between his parents as he nearly always was, has been to visit the Cascata delle Marmora—the Roman waterfall near Terni. He writes:

In the evening, when we came back from seeing the falls, the servant of a young Englishman asked to speak with us, saying that he was alone in charge of his master, who had been stopped there by sudden, he feared mortal, illness. Would my father come and see him? My father went, and found a beautifully featured Scottish youth of three or four and twenty, indeed in the last day of decline. He died during the night, and we were of some use to the despairing servant afterwards. I forget now whether we ever knew who the youth was. I find his name in my diary, “Farquharson,” but no more.

Praeterita is wreathed in emotion, like smoke rising from a peat fire. But it is mostly emotion for the author’s self, for his losses, and for the losses in the world that reflect his own loss. “From what have I not fallen, if the child I remember was indeed myself,” wrote Charles Lamb in 1820, and this is the mood—though far more self-pitying—that is sounded again and again in Praeterita.

But then you come upon this moment of true pathos—the dying “Scottish youth” and the “despairing servant.” It reminds you of all the unnamed, unheralded figures who surface momentarily in the attention of a diarist or a letter-writer and then as suddenly vanish. I am especially fond of the “despairing servant”—I say fond, but I mean pierced. Name unknown, fate unknown, he might have appeared anywhere, in Montaigne’s travel journal, in Goethe’s Italian Journey, in a letter from Madame de Sévigné. But here he is in Ruskin, being remembered by him as he wrote more than forty years after the fact. We will never know what became of him, how he made his way home, or even what use the Ruskins were to him afterwards.

“Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin” is at the Yale Center for British Art through December 8.