Susan Bernofsky sits at a table on stage, her head tilting left, then right. The writer and translator, here a performer, reaches for a napkin—twisted neatly in front of her in the shape of an infant’s bootie—unfolds it, lays it flat, then meticulously reconstructs it. She repeats this sequence from stage right for the entirety of HERZ SCHMERZ (literally, “heart pain”), the new collaboration between the choreographer John Heginbotham and the artist and writer Maira Kalman. The program, which premiered at the Baryshnikov Arts Center last month, is based on texts from the early twentieth-century Swiss Modernist writer Robert Walser. His work, here translated from the German by the British poet Christopher Middleton (1926–2015) and Bernofsky herself, is often bracketed with Kafka’s.

Her performance as “The Napkin Folder” isn’t so different from her work with language: she is scrupulous with the cloth, mindful of tending to every crease and line. She’s also in danger of being overlooked in favor of her fellow dancers, who flit, leap, and shuffle center-stage. For HERZ SCHMERZ, Heginbotham and Kalman, the latter of whom appears in the piece, have strung together a series of vignettes inspired by Walser’s writings that flicker with joy, frustration, and humor. The performance incorporates movement and spoken text—drawn heavily from the Walser short story “Nervous,” a monologue about aging and unease—to depict scenes of unfettered play and immobilizing distress. It’s a compassionate, tender treatment of mortality, but one that eschews the self-effacing understatements that are fundamental to Walser’s writing.

The actors Daniel Pettrow and David Barlow, the dancer Maile Okamura, and Kalman begin the program spread across the front edge of the stage, their hands at their sides and their gazes fixed ahead. Standing still, they begin to speak from “Nervous,” first one at a time and then in a fugue. “I am decaying a little, and I am crumbling, peeling a little.” “That’s what it does to you,” Walser writes in the text. “That’s life. I am not old, not in the least, certainly I am not eighty, by no means, but I am not sixteen any more either.” The text is as tightly wound as the performers, with their rigid shoulders and tense verbal delivery. The pianist Pedja Muzijevic and the cellist Caitlin Sullivan play at stage left, one leap away from the dancers. As the performers’ declarations rise in pitch, and their upper bodies begin to shake like overheated machines—their feet still fixed to the stage—the musicians swoop in with music from the Swiss composer Hans Huber, first joining and then overtaking the monologists, who stop speaking and disperse.

Here, each performer slips into a singular rhythm and movement style. Barlow, his royal-blue sweater stitched with the looping phrase “One Must,” retreats gingerly across the stage, as if he’s skirting some boundary markers only he can see. Pettrow, his gait intentionally wobbly and his movements quicker than the accompanying tempo from Muzijevic and Sullivan, plays the rogue. He wears a “bright yellow English suit” modeled after the one worn by the narrator in Walser’s 1917 novella The Walk, though he also goes barefoot. (“Yellow is right for wind and dancing,” Walser writes in another work, “Helbling’s Story,” about a daydreaming bank employee, drawn from Walser’s experience working odd jobs.) At the start of one group vignette, Pettrow puckishly dips his thumb down when the other dancers raise theirs up.

The performers move in this segment with a sense of play, as though they are conducting a children’s game. There’s no clear logic to their actions, no sure indication of what they are passing judgment on with their thumb gestures. Then prickliness sets back in: when Pettrow whispers to Kalman, she hurls back a hollow, bitter laugh. Kalman, who turns seventy this year, takes steps throughout HERZ SCHMERZ that are reigned-in but wry. Mid-performance, she picks up the seam of her black rain-slicker and hints at a dramatic flourish, only to slightly lift her ankle. When the four performers lie on their backs, rocking their knees left and right, her movements are pointedly curtailed, as if to say, “let the kids take this one.”

*

Since founding his New York-based company in 2011, Heginbotham has created performances that layer choreography with speech, props, and theatrics. In 2015, he premiered Easy Win, a collaboration with the composer and jazz pianist Ethan Iverson that played with the ritual of the dance class—the performers ran through warm-up exercises, practiced lifting one another, and loosely sped through step sequences as if committing them to memory. Chalk and Soot, which was first staged in 2012, took its cue from “Sounds,” a book of poems from the artist Wassily Kandinsky. (Okamura designed the costumes for both productions.) Most recently, Heginbotham received acclaim for choreographing the Tony Award–winning production of Oklahoma!, currently on Broadway.

Advertisement

Heginbotham first encountered Kalman in 2000, when he was a member of the Mark Morris Dance Group and Kalman designed a set for its production of “Four Saints in Three Acts,” based on the 1934 opera by Virgil Thomson with a libretto by Gertrude Stein. They appeared on the same bill again in 2013, for Isaac Mizrahi’s annual holiday production of Peter and the Wolf at the Guggenheim Museum. Heginbotham choreographed the piece, and Kalman played what she characterized in an interview with the museum as “a kind of Upper West Side little-old-lady-duck,” complete with a PBS tote bag.

Their first co-production, The Principles of Uncertainty, emerged out of months of walks they shared. Kalman also appeared on stage, primarily in a speaking role, in that engagement, which shares its name with a collection of her paintings and observations, first published as a New York Times column. Kalman’s hybrid text-illustrations are eccentric and lyrical. Her children’s books include a series about Max Stravinsky, a world-traveling dog and poet. (This July, the Alliance Theater in Georgia staged a performance of the first book, Max Makes a Million, adapted and directed by Liz Diamond, with choreography by Emily Coates.) Among her books for adults is Girls Standing on Lawns, a collaboration with the writer Daniel Handler (better known, perhaps, by his pen name Lemony Snicket) for which Kalman created a dozen original paintings inspired by archive photographs from the Museum of Modern Art.

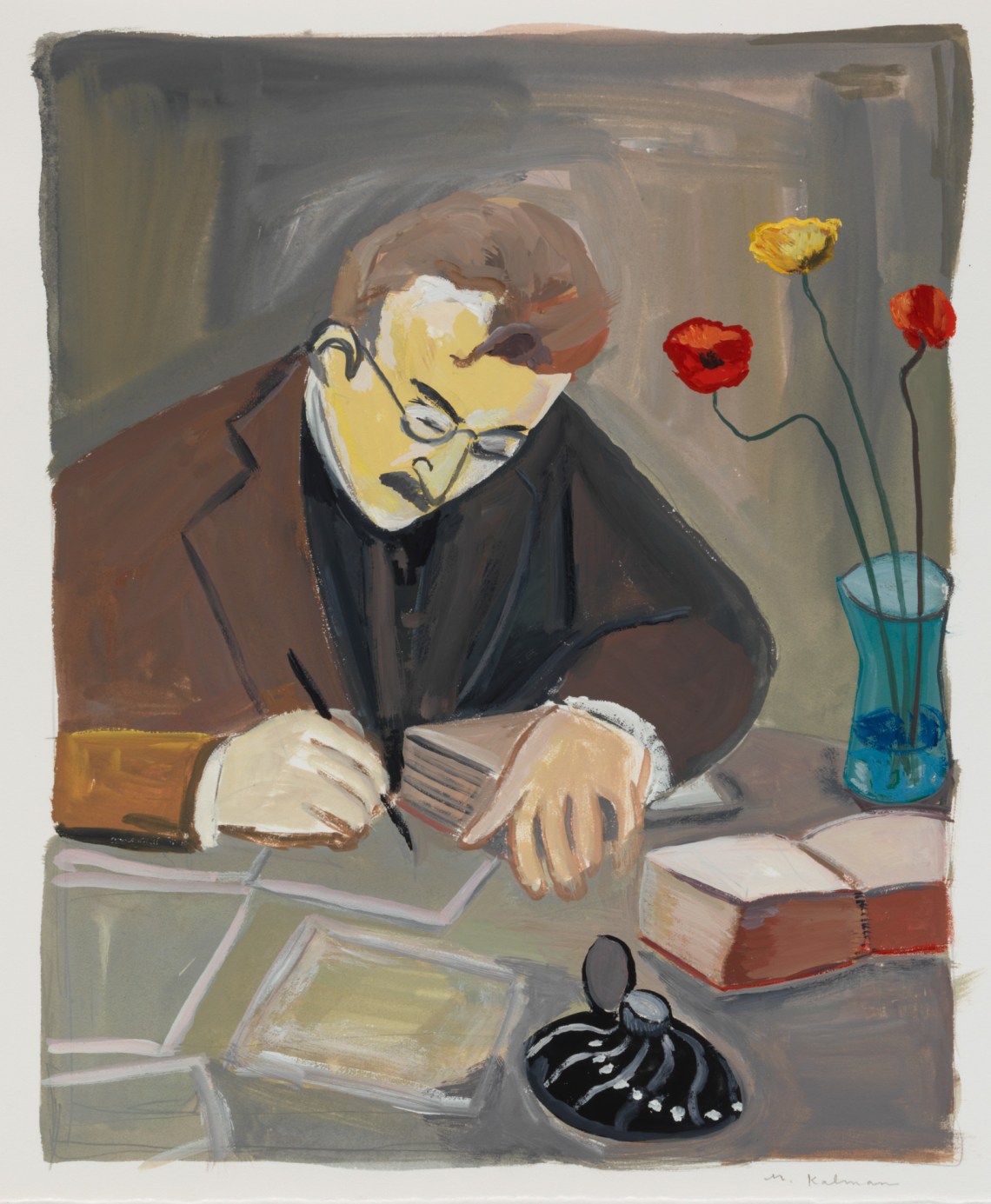

HERZ SCHMERZ isn’t Kalman’s first project inspired by Walser. For a 2012 volume, translated from the German by Bernofsky, of Walser’s “microscripts”—prose pieces he wrote in pencil, on scraps of paper, in a script so small and densely packed they were initially assumed to be in code—Kalman contributed a set of original paintings that offer a compassionate and wrenching account of the writer’s life. In “Some Thoughts on Robert Walser,” she interprets in warm hues—ruby pinks, emerald greens, canary yellows—the home in which he worked as a butler, the rooming houses he occupied, the beds in which he propped up books against his knees. She wonders: “How many corridors did he walk down to how many Rooms?”

The set Kalman has designed for HERZ SCHMERZ is more pared down than her paintings. In addition to Bernofsky’s table, Kalman has positioned a large, upright board at the center of the stage. It’s painted green, with a pair of men’s dress shoes affixed to it, one higher than the other, and a third on the floor. The arrangement gives the illusion of a spectral figure walking up an invisible a set of stairs. It’s an overt, sympathetic homage to Walser, who was often characterized as isolated and withdrawn. “Walser must at the time have hoped, through writing, to be able to escape the shadows which lay over his life from the beginning,” wrote W.G. Sebald in his 1998 essay collection A Place in the Country, “and whose lengthening he anticipates at an early age, transforming them on the page from something very dense to something almost weightless. His ideal was to overcome the force of gravity.”

*

Walser’s work—short prose pieces, novels, poems, and even some theatrical verse—lends itself well to a dance-theater adaptation. Walser was born in Switzerland in 1878, and in 1905, he followed his older brother Karl, a theater set designer, to Berlin. “Karl’s stage sets were fanciful, mysterious, and full of romantic gardenscapes and hanging trees,” Bernofsky notes in her introduction to the Walser collection Berlin Stories, which she also translated. His writing from this time captures his sense of the city’s arts and performance scene. In “A Person Possessed of Curiosity” (1907), he praised theater that dared to “prick and prickle a bit, otherwise it might get dull.” He described a dance performance in “On the Russian Ballet” (1909) as “beautiful wildness ennobled by discipline and tact.” In a macabre, parodic piece titled “Response to a Request” (1907), he provides an unnamed addressee with an outline for creating “a spectacle, a dance, a pantomime, or anything else.” His instructions include subjecting one’s body to a litany of horrors: drawing a knife, unleashing a snake, lighting a cigarette, having the whole set collapse on oneself. The idea was to reveal what the body can endure, and what it can convey. It “is possible,” he concludes, “for one eye alone, open or closed, to achieve an effect of terror, beauty, grief, or love, or what have you.”

Advertisement

Walser’s short prose pieces, which Bernofsky characterized in her introduction to Berlin Stories as a “hybrid of story and essay,” thrum with energy. Walser often set and conceived of these pieces on winding roads, in parks, and across village squares. His own walks served as a sort of release valve: “Oh Lord, enough for now, I have to go out, have to leap down into the world,” Walser’s narrator declares in the 1910 piece “The Metropolitan Street.” “I can’t stand it any longer, I have got to go laugh in someone’s face, I must go for a walk.” Nothing much needed to happen on a given walk for something to seem extraordinary. “In all honesty,” he wrote in “The Park” (1907), “I find it magnificent when a solitary old woman walks down a green avenue.”

Walser was less interested in these works with climactic reveals than with the process of discovery—his writing belongs to the tradition of flâneurism. At the start of The Walk, the narrator feels cooped up (he’s been indoors writing, naturally) and decides to wind his way through town. He dips into the bank and the bakery, the bookstore and the tailor’s shop, his mood shifting with each new interaction. “It is here a question more of a delicate, gentle walk than a voyage or excursion,” he writes, “more of a subtle circular stroll than a forced march.” The Walk was the only of Walser’s work translated into English during his lifetime, by Christopher Middleton. After the novella’s original publication, Walser steadily revised it—so much so that in 2012, Bernofsky produced a new translation of the story based on Walser’s preferred text.

Following a mental breakdown, Walser spent the last twenty-three years of his life in a Swiss asylum and died during a walk on Christmas Day in 1956. In “Some Thoughts on Robert Walser,” Kalman adapted a photo of him taken by the medical examiner, in which he is half-buried in a snowbank, his left arm unfurled, his hat hovering a few feet from his head, his chin tipped back. His face is grey, his body rigid, but there’s a warmth in the painting that the photograph lacks. “I am hoping that he is not Dead,” Kalman writes in the accompanying text, “just enjoying a Refreshing Lie-down in the snow. But the caption, sadly, says he is Dead.” In the painting, she has pictured Walser nestling in a bay of white brush strokes.

*

HERZ SCHMERZ attempts to capture the internal rhythm of Walser’s writings—by turns, digressive, taut, melancholy, and joyous. In a more delicate sequence in the middle of the program, Okamura stands between Pettrow and Barlow and hangs over their clasped forearms. She taps Barlow’s clip-on microphone and begins to recite some Walser text with a slight quiver. Her slack upper body reflects the vulnerability expressed in the lines she speaks. In one of the later vignettes, Pettrow slips his right foot into the shoe on the ground, his left into one, then the other shoe affixed to Kalman’s set piece. Like a rock climber, he hooks his arm on the right side of the structure for stability. His body tilted, he runs through pitched, frantic lines drawn mostly from “Nervous,” with an outsized, booming delivery: “I am holding out and holding on.” “I hope that I am a little nervous.” “Old and used up.”

“When I dance I forget that I am Helbling,” Walser writes in “Helbling’s Story,” “for I am nothing but a happy floating-in-the-air. Thoughts of the office, with its manifold agonies, would not intrude on me at all.” The choreography in HERZ SCHMERZ aims to depict both the “manifold agonies” of daily life and that “happy floating-in-the-air” feeling. After Pettrow unlatches his feet from Kalman’s set piece, he drags it back to reveal the other three performers standing still and unflinching behind it, positioned under metal ladders. Earlier in the piece, the performers dashed behind the board, popped up at the top of it, and peered out at the audience like colorful puppets. The rudimentary mechanics of their trick are now laid bare, and the simplicity of the moment is delightful. Once Pettrow has pulled the set all the way towards stage left, he spins it around and rolls it back to the center, again obscuring his peers. On the other side, Kalman has tacked a bowler hat and a hanger. Pettrow sets his coat on the hanger and steps under the hat. He is meant to look like Walser, and be a stand-in for the writer himself.

In a later vignette, Pettrow, his arms pulled by Barlow and Okamura, glides across the stage like an alpine skier while Kalman tosses snow-white flecks along their path. The moment has charm, but it feels slightly cloying—more like a forced marched than a subtle stroll. It’s worth wondering, in these instants, why Kalman and Heginbotham chose to cast non-professional dancers for this piece, only to have them run through scenes choreographed in broad, gestural sweeps. For all that they and Walser make of pedestrian activities like walking, there’s little of such quotidian movement on stage.

In a climactic moment midway through HERZ SCHMERZ, the performers pause—as Walser did in his 1907 story “The Park,” to remark on his surroundings—to look out into an imagined horizon, and they embrace as though they’ve reached the end of a formative journey. The scale of the moment feels ill-suited to Walser. “From his earliest attempts on,” writes Sebald, Walser’s “natural inclination is for the most radical minimization and brevity, in other words the possibility of setting down a story in one fell swoop, without any deviation or hesitation.” This wistful, valedictory tableau tends to induce just the stream of existential anxieties that pieces like “Nervous” and “The Park” are keen to stanch.

All the while, there is Bernofsky at stage right, her steady hands, her glinting silver ring, and the white dress with a starched crease down its middle, evocative of the pressed shirt Walser might have worn during his brief employment as a butler in a Silesian castle. She’s still folding and unfolding that napkin, and when the lights momentarily dip on the four performers at center stage, the audience leans in for a clap before realizing that this is merely a cue to shift their focus to the solitary translator, going about her task. It’s perhaps the cleverest moment of staging of HERZ SCHMERZ, confirmation that we’ve let our eyes drift, and that we have the capacity to see anew an image that has been in front of us the whole time. This seems to be one of Walser’s priorities: engaging with one’s immediate surroundings as a way to divert focus from debilitating self-doubt and questions of mortality.

“Grouches, grouches, one must have them,” Walser writes near the end of “Nervous,” “and one must have the courage to live with them. That’s the nicest way to live.” HERZ SCHMERZ only feints at this idea of acceptance, without ever addressing it fully. In the closing group sequence, the performers stand shaking, again, near the front of the stage, as their speech decays. They frantically snatch at their bodies, clutching their abdomens and gnarling their wrists. They return, too, to excerpts from “Nervous,” and its despair over aging and deterioration. Their declarations, by this juncture, come off not only as inattentive. Through movement, one would hope, the performers might have some chance of dismantling their seeming self-preoccupation.

Though HERZ SCHMERZ captures some of the more subtle pangs of delight and disappointment that underpin Walser’s writing, the performance resonates more as a homage to the writer than as a translation of his work. Heginbotham and Kalman seem to acknowledge this dissonance in the program’s final beats, when the four performers disperse: Barlow scales one of the ladders behind Kalman’s set piece, Pettrow lays on the ground at stage left (is he meant to look like Walser in the snow?), and Kalman retreats to Bernofsky’s corner of the stage. Okamura, the only professional dancer in the group, remains at center stage, slightly set back from the audience. In an expressive, graceful solo, she hugs herself, clasps one hand with the other, and blows into her open palms as if they’re bearing a small pile of petals. In these closing moments, the performance feels as though it’s just ready to begin—not unlike the way in which Walser’s narrator in The Walk steps out of his home, where he is overcome with dread, and into a world that feels vibrant with possibility. As Walser reminded his readers in “A Little Ramble,” “We don’t need to see anything out of the ordinary. We already see so much.”

HERZ SCHMERZ was performed at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York City, October 10–12, 2019.