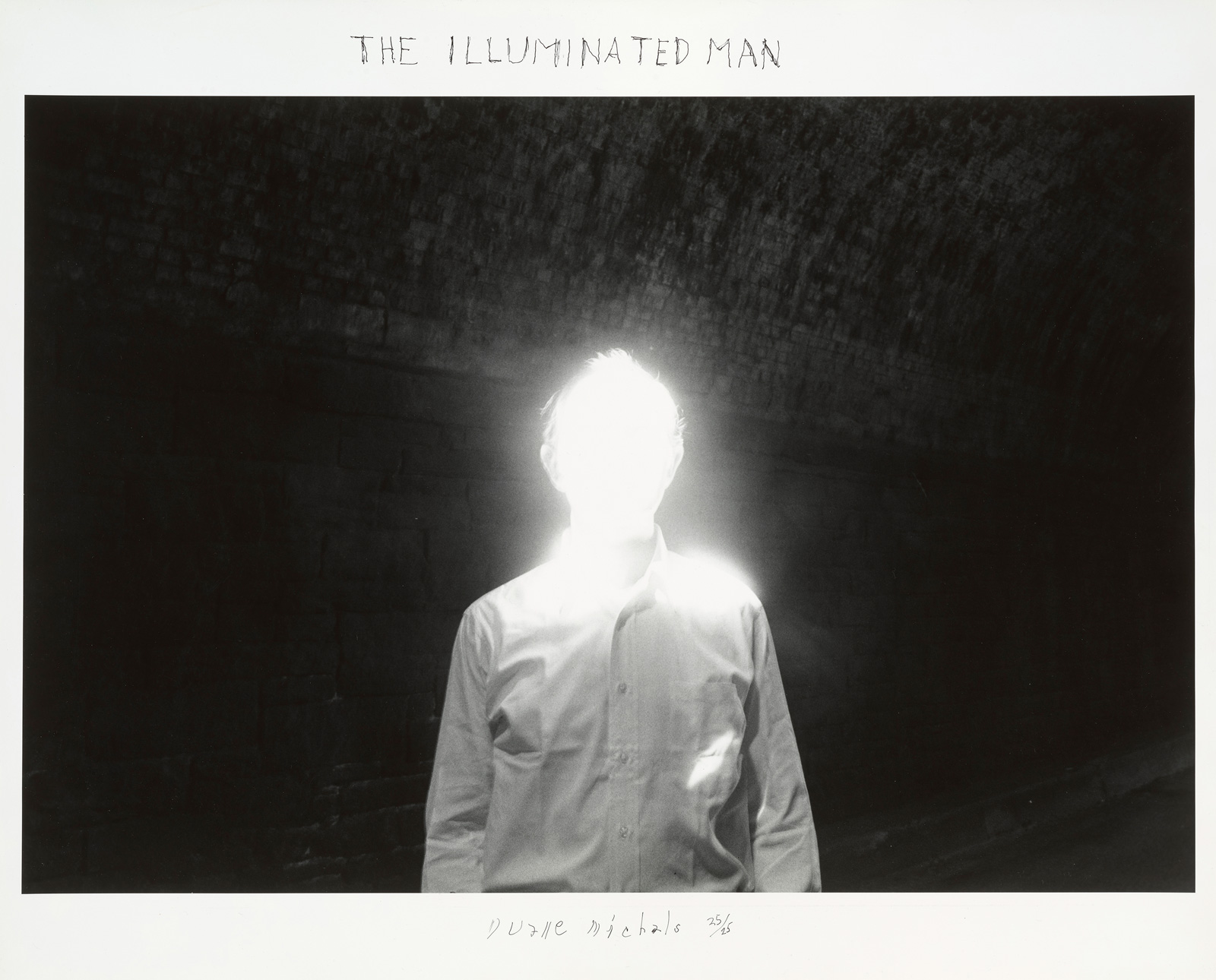

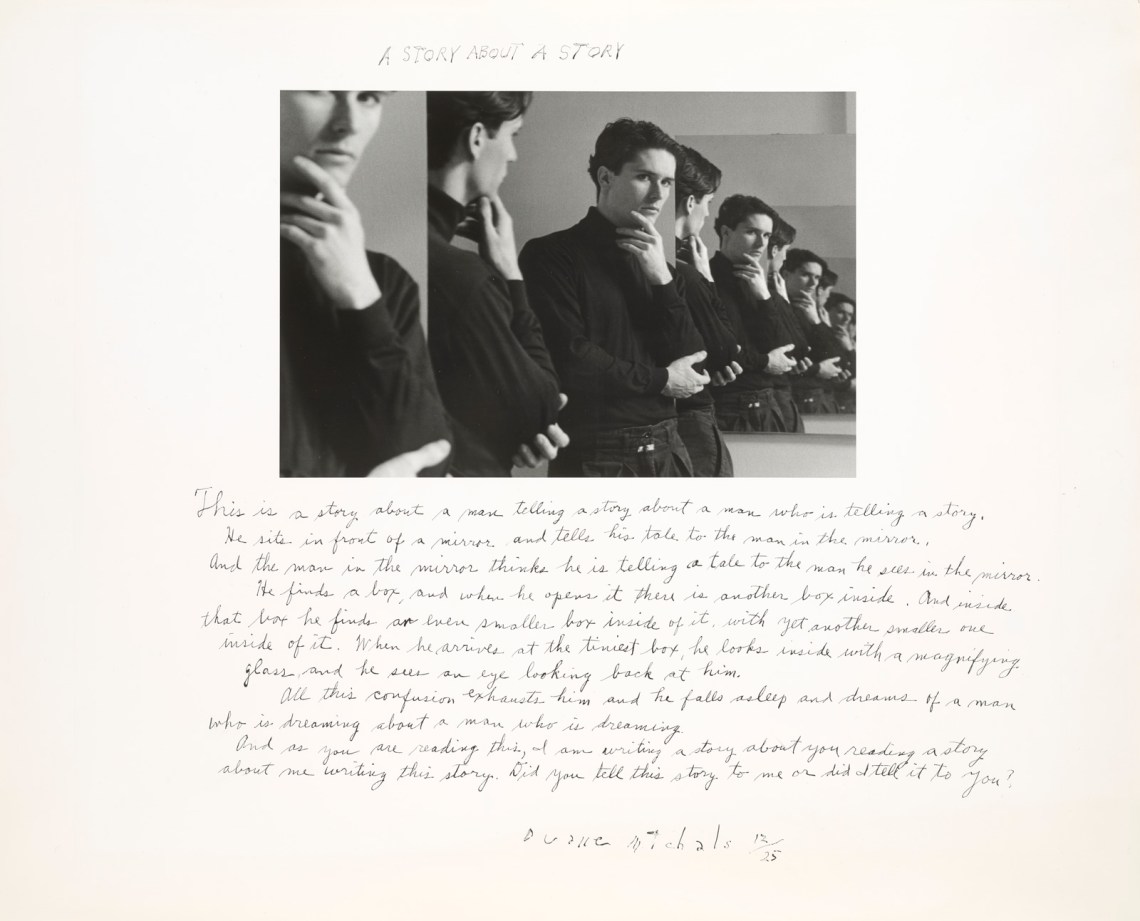

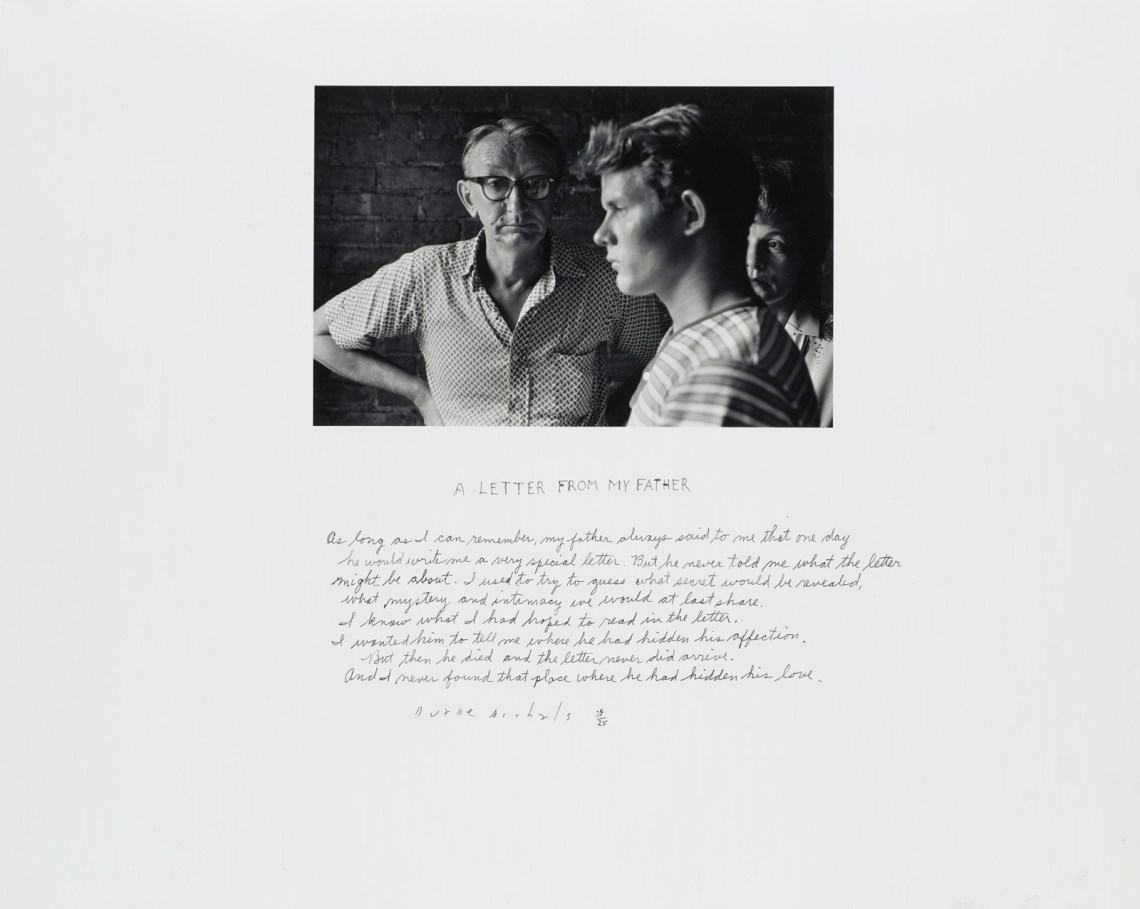

Months before he turns eighty-eight, the photographer Duane Michals is in the full throes of a remarkable old-age efflorescence. Evidence to that effect fairly leaps off the brightly colored walls of his fascinating new exhibition, “Illusions of the Photographer,” at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. Michals has long been renowned for three great innovations: his hauntingly atmospheric, teasingly Surrealistic, almost cinematic sequences of pictorial narratives; his use of handwritten texts on small-scale black-and-white silver gelatin prints (the antithesis of the current rage for billboard-sized digitized color images); and his celebratory normalization of homoerotic male beauty, years before Robert Mapplethorpe’s freak-show fetishism and Bruce Weber’s consumer-culture beefcake. Yet, unlike artists who hit upon a commercially lucrative formula and then crank out endless fungible reiterations, Michals is something of a superannuated Huck Finn, an incorrigibly subversive and inimitably American scamp always lighting out for new creative territories.

It took me nearly an hour and a half to work my way through the single large gallery in which Michals and the Morgan’s astute photography curator, Joel Smith, have assembled nearly a hundred works by him and other artists (including Carlo Galli Bibiena, William Blake, and Egon Schiele, as well as the photographers Lewis Carroll, Eugène Atget, and Irving Penn), along with literary artifacts such as Voltaire’s red leather portfolio, Goethe’s quill pen, and an origami-like paper boat folded by Nathaniel Hawthorne, in a kaleidoscopic mash-up that is part mini-retrospective and part artist’s choice survey. The latter format has become increasingly popular at museums with deep storage that can be raided for neglected holdings to illuminate the guest artist’s own body of work. Here, Smith combed through the Morgan’s quarter of a million objects and discovered an array of treasures that perfectly resonate with Michals’s quirky sensibility. The photographer in turn made the final selection, and even added items from his personal collection, including Victorian illustrated children’s books of the sort that beguiled the Surrealists. The collaborators then grouped their finds under ten rubrics that reflect the subject’s major concerns: Death, Illusion, Image and Word, Immortality, Love and Desire, Nature, Playtime, Reflection, Theater, and Time.

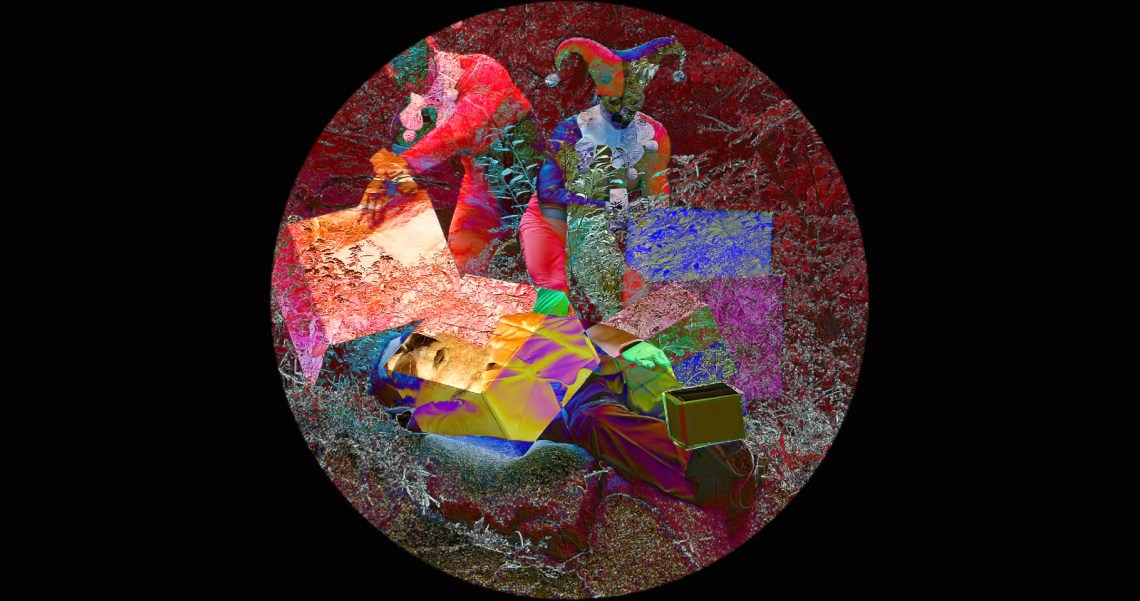

Among the many surprises are sixteen short color films (with running times from under two to over twelve minutes) that Michals has produced and directed since 2015, all of which will be screened at the Morgan during the run of the show. They range from a scatological one-liner (Trickle Down, 2018, in which Michals urinates on a Rolls Royce, his commentary on conspicuous consumption) and a tense domestic drama (Interruptus, 2018, features a woman walking in on her husband as he puts the moves on another man), and from topical political protest (Deport Trump, 2016) to an enigmatic fantasy that blends Commedia dell’Arte, Cocteau, and Sixties psychedelia (YORT, 2019). Also on view are several other late-life Michals enthusiasms, including the anonymous nineteenth-century tintypes that he overpaints with abstract motifs inspired by his favorite modern art movement, Cubism. There are also examples of his postmillennial fan-shaped color photos inspired by nineteenth-century Japonisme and epitomized by a lyrical quartet of views of his upstate New York garden in all four seasons.

I came away from this physically compact—yet psychically enlarging—display with a feeling of utter exhilaration that I haven’t often had in recent years of gallery going. It also occurred to me, after this latest time-out-of-mind immersion in the personal universe that the photography critic Andy Grundberg has called “Duane’s World” that Michals might be best described as a magus—a sorcerer who uses means beyond our ken to explain mysteries of existence that normally elude us.

Always industrious, Michals has been especially productive since the death, two years ago, of his life partner, the architect Fred Gorrée, with whom he’d lived since 1960 and married in 2011. Gorrée suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease during his last seven years, when the photographer attentively cared for him in their townhouse in the Gramercy Park neighborhood. Michals—who, like writers including Joan Didion and Nora Ephron, considers everything that happens to him potential subject matter—collected Gorrée’s random utterances during his dementia and included some of them in his 2014 book ABCDuane: A Duane Michals Primer. Those pronouncements could be as Surrealistic as some of Michals’s photography—“I wonder what Marco Polo’s doing now?”—or like rays of light piercing through a dense cloud cover, as when Gorrée suddenly declared, “Why are we here? To help each other.” Whether Michals’s new burst of creative energy is attributable to losing himself in cathartic activity after his bereavement—a not uncommon and often effective remedy for grief—or perhaps because of an increased sense that time’s wingèd chariot is bearing down on him I do not know, but it is inspiring to witness such renewed vigor at his age, whatever the reason.

Advertisement

As a child of the Great Depression—he grew up just outside Pittsburgh, where his father was a steelworker and his mother a salesclerk—Michals has always had a strong work ethic and was never ashamed to accept commercial assignments that have funded his parallel art career. Although the Morgan exhibition includes no examples of his advertising images (which were always unattributed on the page, unlike the present-day practice of naming celebrity photographers), it could have incorporated them without any taint of the marketplace. Still implanted in my mind’s eye is the breathtaking double-page-spread he did in 1991 for the launch of Estée Lauder’s latest perfume, Spellbound. His tight black-and-white head shot of a man and a woman facing each other in profile has the iconic power of the legendary cinematographer Sven Nykvist’s very similar use of black and white close-ups in Ingmar Bergman’s psychological drama Persona (1966). There is no need to apologize for work of this quality, and indeed when some self-righteous young photographer rudely told him, “I’ll never sell out,” Michals coolly replied, “You’ve got nothing to sell.”

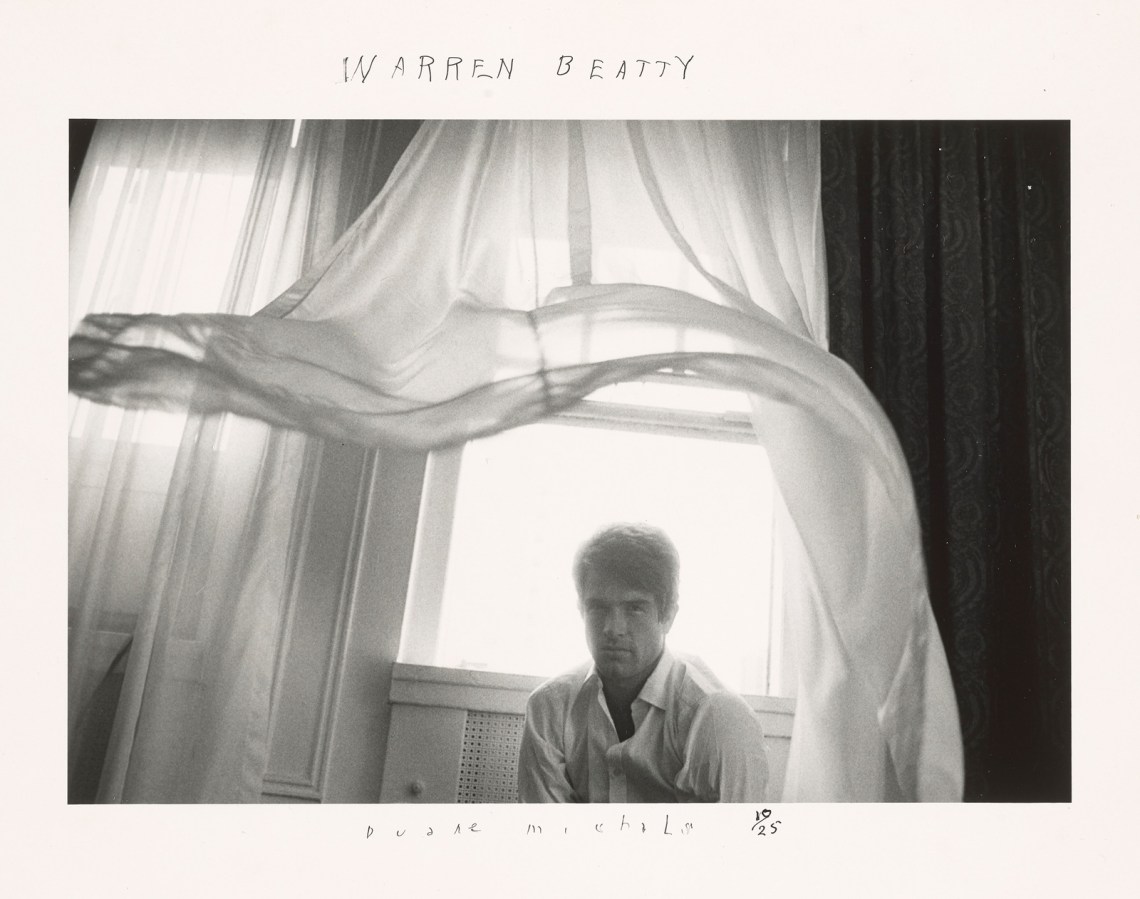

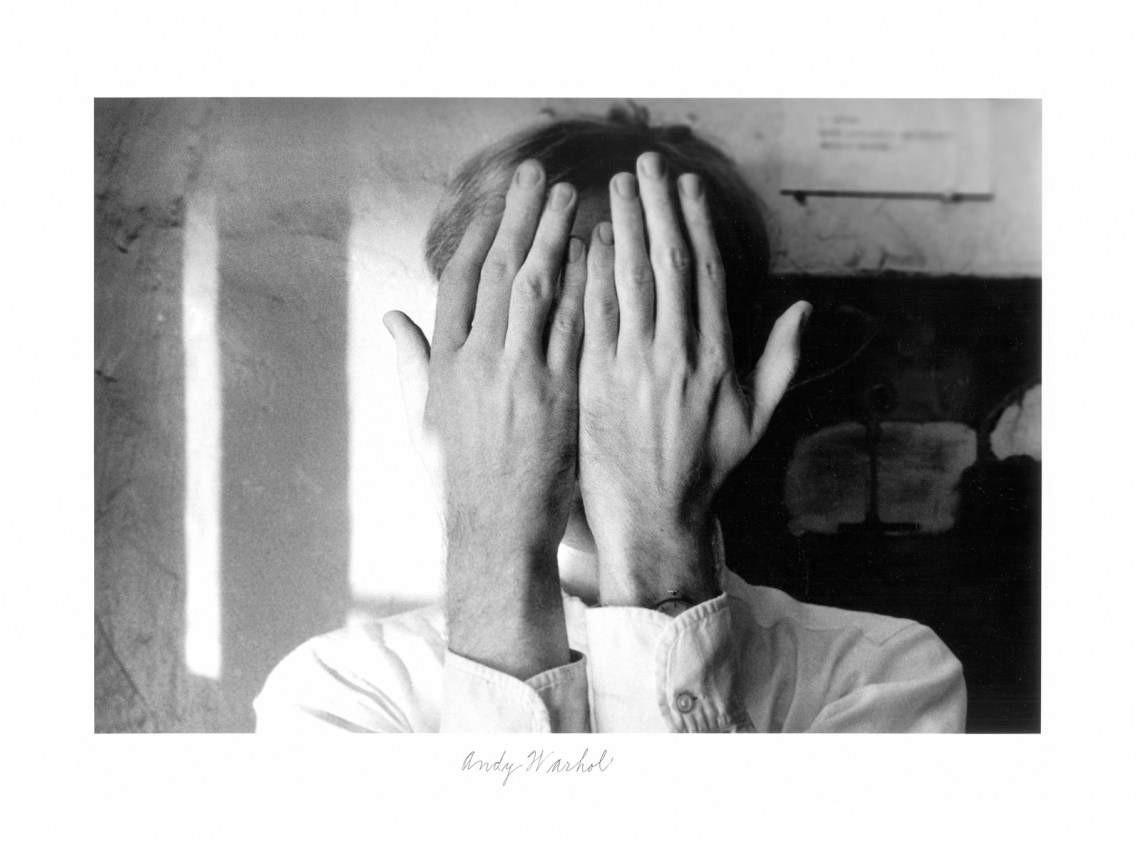

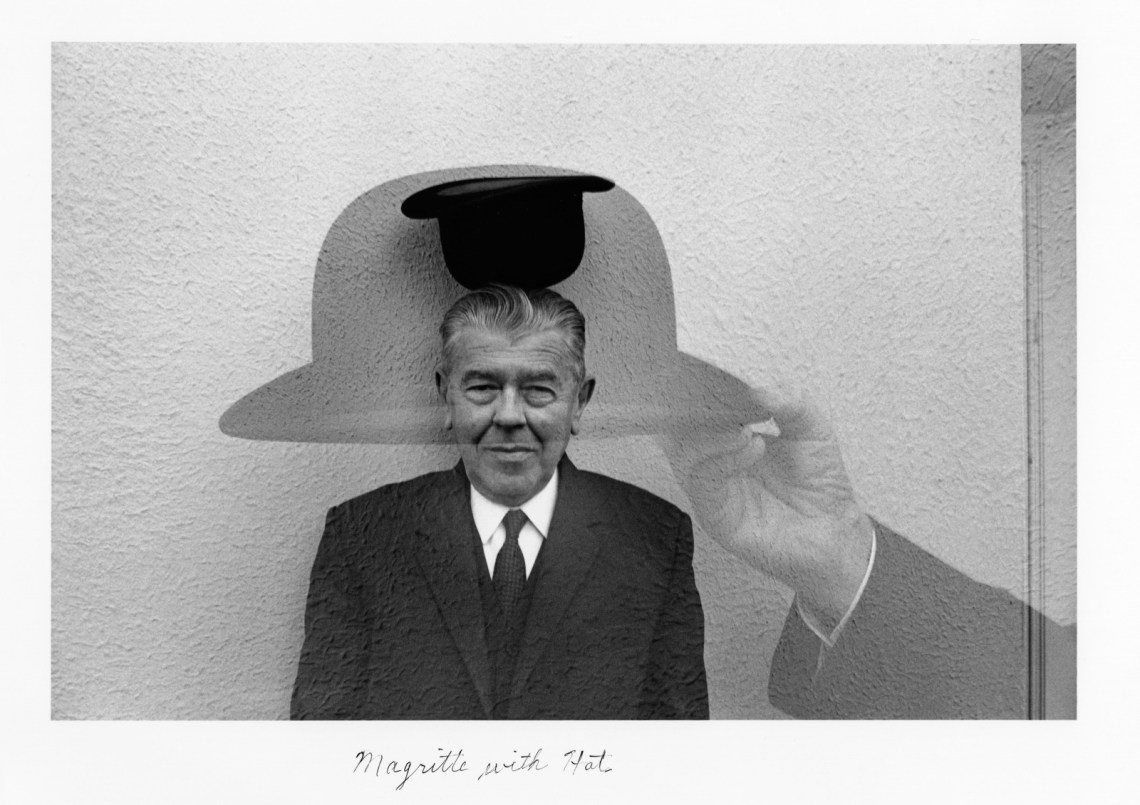

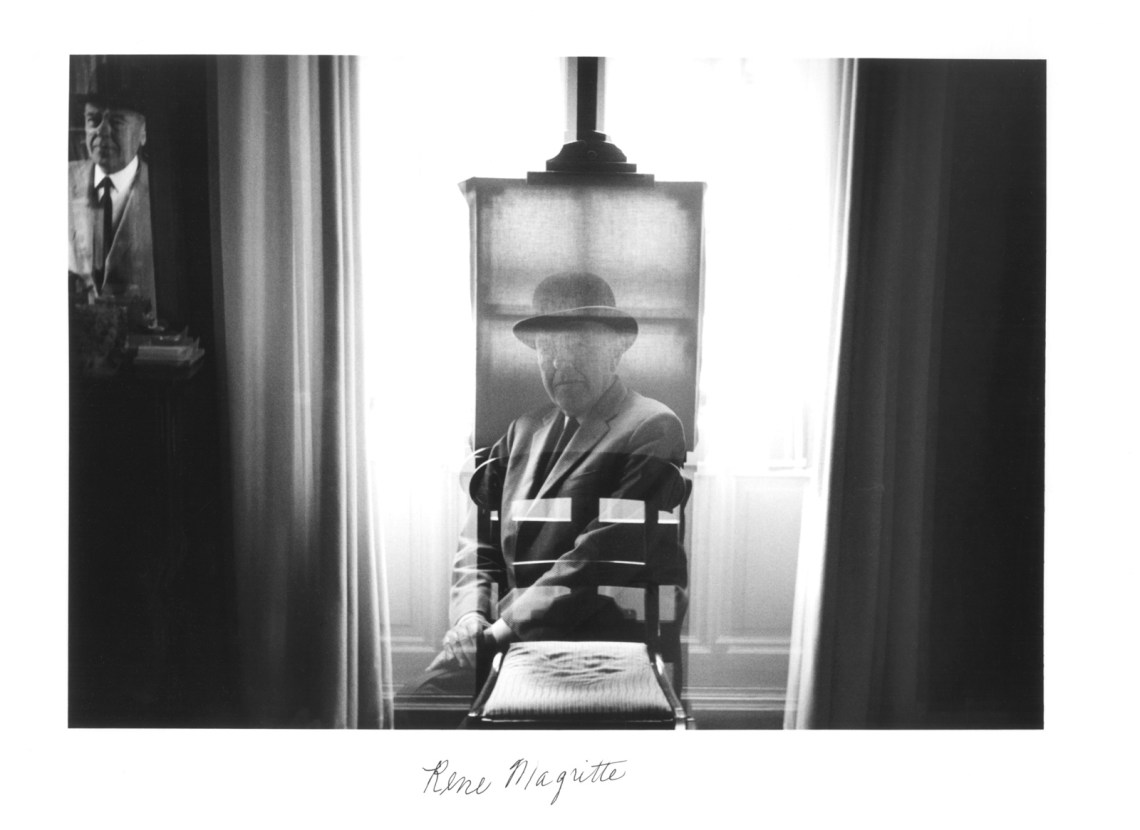

The spheres of commerce and art have intersected for Michals when, for example, he’s been commissioned to photograph cultural luminaries because of his uncanny ability to capture an aura of their work through his insightful portraits of the artists. This was never more evident than in his justly celebrated 1965 series on Réné Magritte, at home in Brussels. The shoot occasioned an unforgettable channeling of the Belgian master’s spirit through a double exposure image of the bowler-hatted artist sitting in front of a blank canvas and appearing to simultaneously morph into the picture plane and vanish from the room. I’m hard-pressed to name any other photograph of an artist more evocative than this one.

Magritte tops Michals’s personal artistic pantheon (along with “[t]hree people I met [who] intimidated me to the point of being speechless: Giorgio de Chirico, Robert Frank, and Saul Steinberg”), as he tells Smith in their uncommonly informative catalog interview. Their probing interchange also offers a great deal of otherwise fresh personal information about its subject, who, though hardly closeted by any possible definition, has always been extremely discreet about his private life, in the same way that countless other high-achieving gay men in the postwar New York art and design world were. Yet it comes as news when he talks to Smith about the invariably beautiful young men whom he recruited for his art photography over the years and admits that, “I got involved with my models—I fell in love with my models—but my models were always straight.”

Although death and immortality are recurrent motifs in Michals’s art—“Whenever some magazine does an article on life after death I get a call,” he once told me—his increasing defense against actuarial reality is another of his major themes: humor. One wall label in the photographer’s distinctively rangy pen-and-ink script reads, “I decided what I wanted engraved on my tombstone: ‘Having a wonderful time, wish you were here.’”

Although Michals in old age can be as avuncular as his great avatar Walt Whitman—the Good Gray Gay Poet (to slightly tweak the famous nickname conferred by Whitman’s great friend, William Douglas O’Connor)—there is also a restless persistence that underlies his explorations into metacognition: thinking about thinking, or knowing about knowing. The conclusion that comes across so clearly in his thought-provoking “Illusions of the Photographer” is that whatever we know, attempt to know, or can’t possibly know, we are all winding up at the same destination. But that inevitability does not dampen this philosophical explorer’s determination to make some sense of what he’s rightly called questions without answers—the Big Things in Life—and his curiosity and vision remain undaunted and undimmed as he heads toward his tenth decade.

“Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan” is on view until February 2, 2020. A catalog is published by the Morgan “Duane Michals: Mischievous Eye,” and an exhibition of Michals’s most recent work will be on view at the D.C. Moore Gallery in New York City from November 15 to December 21, 2019.

An earlier version of this article misidentified the Estée Lauder perfume advertisement that Duane Michals photographed as “Beautiful” from 1985. It was “Spellbound” in 1991.