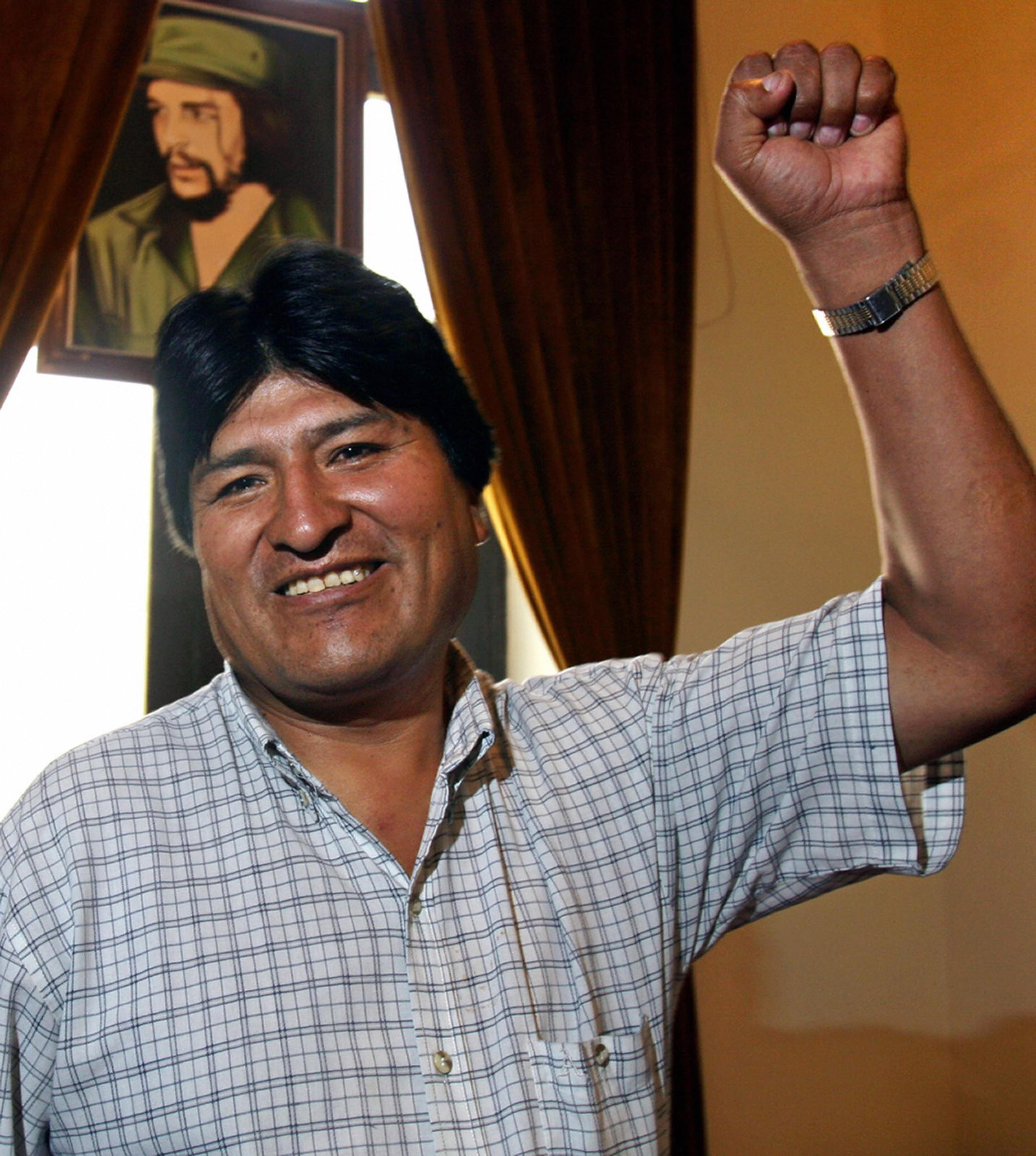

On the night of Evo Morales’s 2006 inauguration as president of Bolivia, the streets of La Paz, the country’s capital, were electric. A man who had once fed on discarded orange peels as a boy was becoming his nation’s leader. For the first time in the country’s history, the indigenous majority would look to the national palace and see one of their own, a president who came from among them and knew their lives firsthand. The streets were filled with both the humble and an assortment of Latin America’s glitterati: Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez zipped by in a tinted-window SUV; the aging Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano prepared to deliver an address. As I wound through the thronged streets in a taxi, the Aymaran driver behind the wheel said to me, shaking his head with a smile, “Imagine, a campesino is going to be president!”

But the moment I remember most came after the formal ceremony in the Congress, when Morales—or simply “Evo,” as most people called him—arrived at the stage in the middle of Plaza San Francisco, a place where, three years earlier, people had been shot and killed by the corrupt political order that was then swept away. A sea of tens of thousands spread for blocks, and Evo was as buoyant as I’d ever seen him. “You know what?” he proclaimed to the crowd. “I think the presidential palace is too big for just me. I am going to ask the vice-president and the speaker of the House to live there as well!” People cheered. Then he looked over, with a sly eye, to where the vice-president and his female partner stood on his right. “That’s OK, he wouldn’t have to sleep there every night!” People roared.

Beyond politics and ideology, it was the wild informality and humility of it all that made me love Bolivia that night as much as I ever had in my family’s nineteen years there (from 1998 to 2017). And that is why watching Evo’s resignation on Bolivian television on a Sunday morning three weeks ago was so dreadfully sad. Something that had begun beautifully, Bolivia at its best, had ended in a familiar scene of a leader chased out by the anger of the people, flying off to another country. And then it unleashed a wave of violence that has already claimed more than a dozen lives, and counting.

The end of Morales’s historic presidency has the quality of one of those inkblot tests in which everyone sees what they want to see. The global left, from British Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn to an assortment of foreign intellectuals, immediately denounced what had happened as a military coup, linking it in the public mind to the old, familiar scenes of tanks rolling into South American capitals. Those who have long hated Evo declared it a blow against the evils of socialist dictatorship. But if I learned anything in my time in the country, it is this: nothing is simple in Bolivia, and such was the case with the rise and fall of Evo Morales.

*

Morales was always a double-sided coin. On the one side, he was unquestionably a man of charisma. At a party a few weeks before his first election, he so charmed my toddler daughter that she asked him to dance. And there was never any question that he had a deep and genuine concern for the poor. But he also possessed an authoritarian streak that made even close allies nervous. In the run-up to the 2005 election that brought him and his Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party to power, I sat in on a series of meetings with leftist social movement leaders from around the country who debated what they called “their Evo problem.” He was positioned to become the first serious candidate of the left in decades—and what already worried them was their personal experiences of how he handled power.

Once in office, consolidating that power became Evo’s top priority. The MAS drafted and won public approval for a broad new national constitution. Among its many provisions was a change that would allow Evo to run for a second term. Morales and his allies set about vanquishing their adversaries on the right at the polls, but sometimes also in violent street conflict. They handled their critics on the left by enticing some to become members of the government and branding those who resisted as US pawns.

With his base solid, Evo began to do some very good things. By bringing the nation’s once-privatized natural resources back under state control at the start of the global commodities boom, he built an industrial foundation that produced solid economic growth through the entire global recession following the 2008 financial crash. His government used those funds to build schools and health clinics, to pave roads, and to establish a cash subsidy program to help children stay in schools. Poverty rates fell and indigenous pride was on the rise. In his second election, in 2009, Morales dispatched his opponent by a thumping margin of almost three to one. On the platform of his national popularity, he also thrust himself forward as a potent international symbol, making powerful speeches around the globe on indigenous rights and the protection of Mother Earth.

Advertisement

Back home in Bolivia, however, Evo’s actual commitment to both those causes was increasingly called into question. This tension came to a head in 2011 when Morales declared that he would ignore the vehement objections of local indigenous communities and build a highway through the TIPNIS rainforest in the country’s east. In protest, those communities mounted a long and difficult but high-profile march to the capital. Morales met this demonstration with brutal police repression that was broadcast on national television. When the women marchers yelled their dissent, Morales’s police bound their faces with masking tape to shut their mouths. Dozens of people were injured in the conflict, and a baby died. The shine on Evo’s presidency began to look tarnished.

In 2014, Morales broke a long-standing pledge against seeking a third term, arguing that his first term had been under the old constitution and didn’t count. This sparked new grumbling about his disrespect for democratic rules, but he was reelected once more, again by a wide margin. Soon after, he announced that he wanted to seek a fourth term, a move that would extend his time as Bolivia’s president to an unprecedented twenty years. Conceding that he was not allowed to do so under the constitution his own party had written, he agreed to let the voters decide in a national referendum. In February 2016, by a narrow margin, Bolivian voters said no.

But Morales and his allies were determined to find a way to stay in power. Some of their motivation was a genuine desire to continue to advance their vision for the nation. But many in the party were anxious to hold onto the personal opportunities afforded by controlling the government. Over time, the Morales administration, like so many Bolivian regimes before it, had suffered a string of high-level corruption scandals.

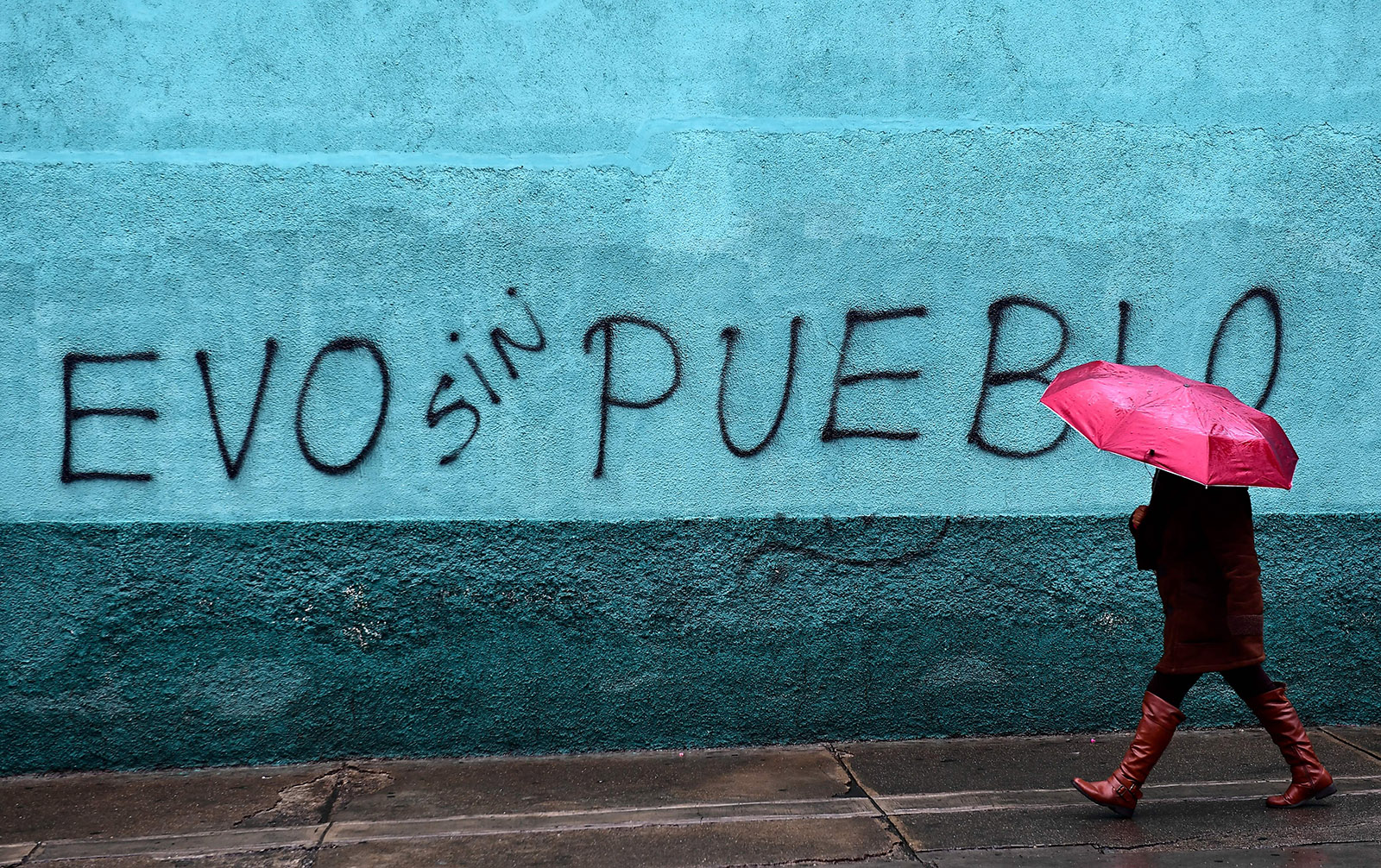

In 2017, Morales’s handpicked Supreme Court justices issued a ruling as transparently compliant as it was legally flimsy. No matter what the nation’s constitution said, the court declared, it was subservient to Evo’s “human right” to run for the presidency for as many terms as he wished. For both his traditional adversaries and growing set of critics among former supporters, it seemed that Evo really was intent on being president for life—protests erupted across the country under the banner “Bolivia Said No.” For Bolivians looking north to the disintegration of Venezuela under one of Morales’s closest allies, strongman Nicolás Maduro, Evo’s abuses of democracy stoked fears that Bolivia could be headed for the same. But Evo had no intention of stepping down.

*

Bolivian elections are a spectacle in themselves. Voting is mandatory, and all car and truck use is banned. From Friday evening onward, until the Sunday balloting is complete, the purchase of alcohol is also prohibited. These rules mean that people across the country all walk to the polls, sometimes for miles, in a festive atmosphere of empty streets. Then they return home to start drinking whatever they’ve laid in before.

Yet the presidential vote held on October 20, 2019 took place under a cloud of illegitimacy. The opposition, from the right, the middle, and the left, had loosely allied itself behind Carlos Mesa, a gray-bearded former president and political moderate. Under the new Bolivian constitution, if no candidate receives a majority and if the leader finishes with a vote margin of less than 10 percent, the top two finishers head to a runoff vote a few weeks later.

On Sunday night, as the voting results were being announced on television, this is exactly where Morales and Mesa seemed headed, with Evo leading in the vote count by just under 10 percent.

Then, suddenly, the vote-reporting stopped, for nearly twenty-four hours. When it resumed, Morales’s margin had risen to just over the 10 percent he needed to win outright. Morales and MAS claimed victory. The opposition claimed fraud, setting off a scramble to determine what had happened and what the actual results were.

Advertisement

In the days after the vote, opposition forces in all the major cities of the country organized shutdowns in protest. Schools were closed. Businesses were shuttered. Roads were blocked. Morales’s supporters in rural areas retaliated with actions of their own, including blockades of the main highways leading in and out of the cities. From the presidential palace, Morales cheered them on through the media and Twitter, saying that they should see if the cities’ resolve remained strong even if their food supplies were cutoff. Opponents accused the president of trying to starve his people into submission.

In Santa Cruz, the country’s second-largest city and always the heart of rightist opposition, the protests were fierce, and the head of the local Civic Committee (a coalition of local interest groups), Luis Fernando “Macho” Camacho, made a play to seize center-stage in this national drama. A forty-year-old lawyer and conservative Catholic with long ties to right-wing extremists in the lowlands, he attempted to travel to La Paz with a resignation letter he said he would make Morales sign.

Violence began to break out around the country. In Cochabamba, the peaceful high-valley city where my wife and I had lived and raised our three children, a teenager protesting Morales was killed. In the small rural town of Vinto, the MAS mayor was marched from her office by opposition thugs who cut her hair, covered her in red paint, and forced her to walk barefoot through the streets. When I called my friends in Bolivia, they told me they feared worse was to come.

Both the governing party and Mesa’s agreed to have the Organization of American States (OAS) audit the voting and results. The organization’s October 30 report, written in the technical jargon of systems analysis, ultimately concluded that the vote was too riddled with irregularities to be certified as reliable. The computer systems used for counting the vote had been tampered with. A quarter of the sampled tally sheets showed signs of interference. The last-minute surge in Morales’s support was deemed “highly unlikely,” based on statistical analysis. A competing analysis done by a left-leaning Washington policy institute claimed the charges of fraud were overblown.

Even so, the OAS report, combined with local news reports of ballot material stuffed in trash cans, the resignation of a senior election official, and evidence of other low-tech efforts at fraud combined to erase the legitimacy of the vote for all but Morales’s most loyal supporters. The protests in the cities grew, demanding a complete rerun of the election administered by an independent body. Morales and his allies objected and declared the original results valid.

As the uproar mounted, on November 8, rank-and-file police officers climbed to the rooftop of the central police station in Cochabamba, waving Bolivian flags and declaring themselves “in mutiny” against the national government. They said they were unwilling to help Morales quash protests that included many of their own family members. Like dominos, one city police department after another fell in line with the rebellion. Even in La Paz, Evo was informed that the police would no longer take action against his opponents.

Morales retreated and announced that he would support a fresh vote supervised by an independent body. But political events in Bolivia have a way of taking on a momentum of their own. I witnessed this firsthand on many occasions—such as in 2000, when the people of Cochabamba kicked out the Bechtel corporation in the famous Water Revolt (after the infrastructure conglomerate sent water tariffs skyrocketing), and again, in 2003, when the nation rose up to oust President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada after his repression left dozens dead in the highlands. Now Morales was the victim of such a public tide. His insistence on running for a fourth term and his defense of an election that looked stolen proved too much.

The opposition’s calls for a new vote changed to a general demand for Evo’s resignation, driven hard by a newly emboldened right. On November 10, as the nation braced for more violence, one former Morales ally after another joined the demand for resignation, including the powerful Central Obrera Boliviana, the country’s huge federation of labor unions. Soon after that, the Bolivian army added its voice to the call for Morales to go. The army’s commander, General Williams Kaliman, a Morales appointee, issued a statement: “After analyzing the conflicted domestic situation, we ask the president to resign his presidential mandate to allow for pacification and the maintaining of stability, for the good of our Bolivia.”

A few hours later, a weary Morales sat before cameras and announced his resignation. Evo told the Bolivian people that he had been the victim of a “civic coup,” but maintained that “it is my obligation, as the indigenous president and as the president of all Bolivians, to look for peace. For this and many reasons, I am resigning.”

While activists in far-away political capitals like London and Washington settled in to debate the semantics of the word “coup” and whether Bolivia had had one, Bolivians turned their attentions to two, simultaneous dramas unfolding in the country. One was Morales’s acceptance of asylum in Mexico and departure from the country. The other was Bolivia’s problem of sorting out its interrupted line of presidential succession. The vice-president and the respective heads of the Senate and House of Deputies, all Morales allies, had also resigned their leadership posts. Finally, on November 12, in a session of Congress boycotted by MAS, the Senate’s vice-president, Jeanine Áñez, a conservative Christian deeply embedded in the right-wing opposition but next in line, declared herself the interim president.

From the start, Áñez signaled that she didn’t see her short time in office as simply a bridge to new elections. On her arrival in the capital, she held up a giant leather-bound book and declared, “The Bible has returned to the palace!” She replaced Morales’s cabinet ministers, who’d resigned, with allies from the political right and not a single indigenous man or woman among them (only later did she appoint one). In both manner and action, she had the look of someone who had just been elected with a great mandate for change, rather than a back-bencher elevated to the post by accident and for a constitutional limit of ninety days.

Soon, the conflict in Bolivia’s streets became deadly. Outside of Cochabamba, thousands of coca growers, the core of Evo’s political base, marched toward the city center. On the outskirts, a barrage of police and military stopped them, triggering three days of pitched battles that left nine Evo backers dead and more than a hundred wounded. Police would later claim that the cocaleros were armed and had set off dynamite. A human rights attorney I know, who was on the scene, called it a slaughter. Áñez issued a decree granting a preemptive amnesty to soldiers and police—what some called “a license to kill.” On November 19, in the city of El Alto, not far from the capital, Morales backers sought to occupy and burn a gas storage plant. The police and military actions there left eight supporters of the former president dead. The day beforehand, in a neighborhood nearby, a young police officer was beaten to death by forces demanding Evo’s return.

*

We speak with our friends in Bolivia often these days, to let them know we are thinking of them and to listen to their accounts of what is happening on the ground. They come from all walks of life and have different points of view on politics. Some are activists and some have no political involvements at all. But what they have in common now is fear. They tell of motorcycle gangs that ride into their streets with unclear intentions but obvious menace. Families our children once went to school with had the hillside behind their homes set afire and can hear the gunfire just up the road. Neighborhoods have organized themselves to protect their own safety. Warning sirens wail in the night, and people in our old village are told to turn out their house lights.

“We stay inside. We don’t know who is going to attack us,” said one friend of many years, crying through our entire call.

“I worry about my son in the army,” said another.

“There is no fruit in the market anymore and the other food is running short,” we heard from a mother with a toddler son.

Bolivia in its normal state is a place of splendid peace. It was a country where our rural neighbors tended their cows and planted corn, where the woman who sold us our vegetables in the Sunday market teased me about my big gringo feet. But it is also a place where violent political convulsions can arise seemingly out of nowhere; along with our Bolivian friends, we lived through many. This one feels different, though. No one knows how it will end.

It didn’t have to come to this. Pablo Solón, a well-respected Bolivian activist whom I have known for two decades, was at the center of Evo’s government from the start. He served as Morales’s climate negotiator and later as his ambassador to the United Nations. But he broke with Morales years ago over the government’s relentless destruction of the environment in the name of development. Interviewed after Morales’s resignation, Solón shared the same lament as many who were a part of that joyful night in La Paz fourteen years ago. “If he would have respected that referendum, he would have finished his third term as probably the best president in Bolivia,” he said. “But he didn’t do that.”

Constitutions have a purpose. They keep a nation from running entirely off the rails. Bolivia is living that lesson now in the hardest of ways. It would be a good lesson for us to heed right now in the US, as well.