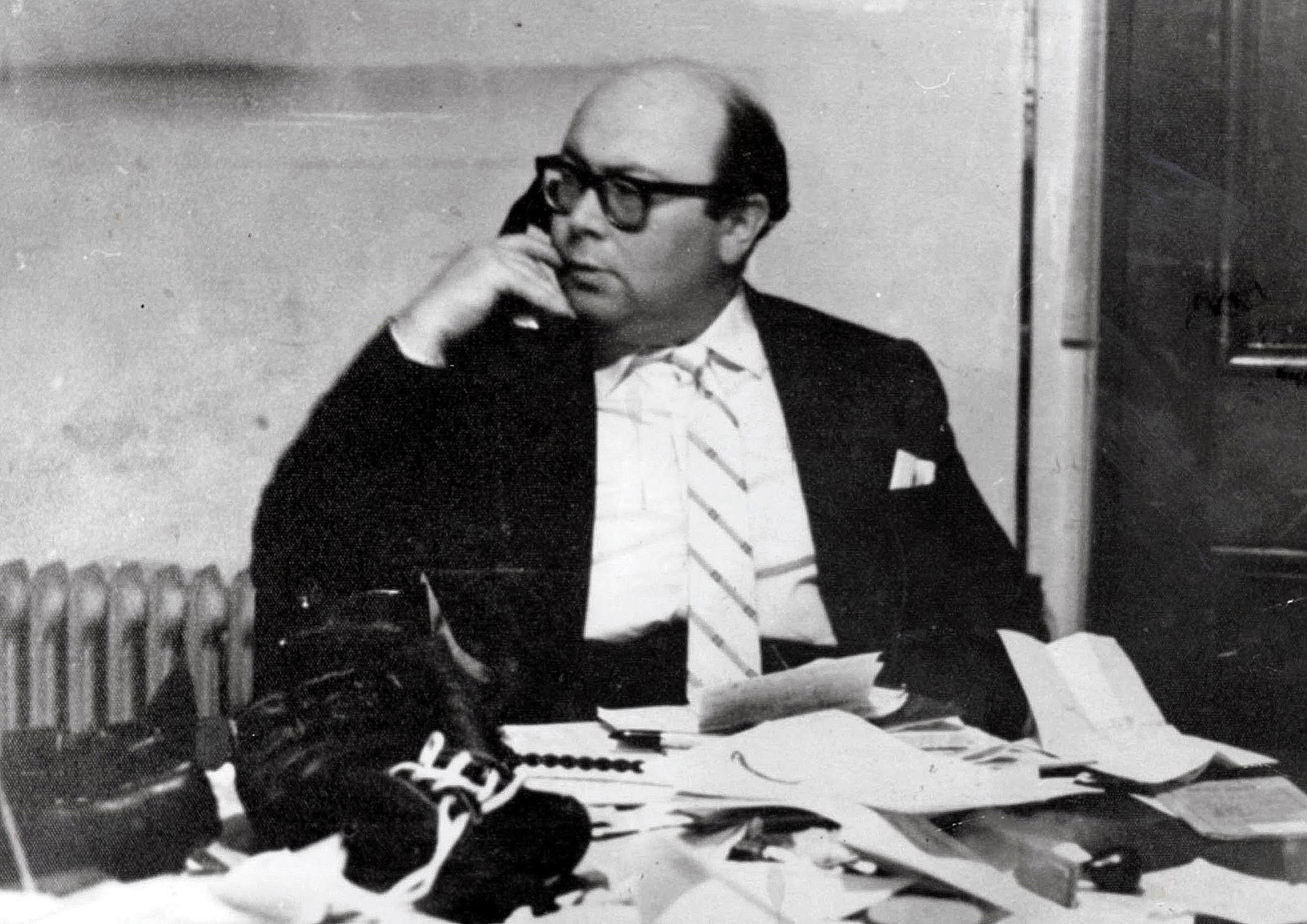

In the early hours of November 29, 1962, Peter Rachman, a Polish-born property developer, was driving his Rolls-Royce home toward Hampstead Garden Suburb, north of London, when suddenly he felt ill. The bald, corpulent man pulled over to the side of the road and, sweating heavily, spent some time doubled over the steering wheel. After a short while, Rachman felt well enough to complete his journey. Once he reached his mock-Georgian mansion on fashionable Winnington Road, he took to his bed. At 9:45 the next morning, after a fitful, uncomfortable night, Rachman suffered a heart attack and his wife, Audrey, called for an ambulance. Rachman was admitted to Edgware General Hospital; at 4:45 PM, he suffered a second, this time fatal, heart attack. He was forty-three years old.

The following Thursday, Rachman was buried in Bushey Jewish Cemetery in Hertfordshire. There were only a handful of mourners, principally his wife and some members of her family. Peter Rachman had arrived in Britain sixteen years earlier as an impoverished ex-serviceman, and had remade himself to the extent that, at the time of his death, he was a successful businessman who habitually sported diamond cufflinks, tailored suits, and crocodile-skin shoes. Despite such sartorial flamboyance, Rachman’s was a private life, and he remained largely anonymous. There were no obituaries, and no public acknowledgement of his passing. This would soon change. Within a few months of his death, the British public would become extremely familiar with the name of this Polish émigré, but his posthumous fame was hardly flattering.

On July 14, 1963, The Sunday People published a lead story supposedly exposing the late businessman’s nefarious practices under the banner headline “Rachman—These Are the Facts.” The paper identified Rachman as a central figure in an “empire based on vice and drugs, violence and blackmail, extortion and slum landlordism the like of which this country has never seen and let us hope never will again.” With no fear of a libel suit from a dead man, other newspapers followed and targeted Rachman, although there were plenty of examples of unscrupulous landlords at work in London. The day after The Sunday People’s splash, the BBC broadcast an episode of its flagship investigative program Panorama that depicted Rachman as a degenerate racketeer in tinted glasses, with a cigar in his mouth and a roll of banknotes in his pocket.

The BBC reported that in order to extract maximum profit from his houses, Rachman would not hesitate to “Put in the schwartzers”—as those in the real estate world commonly termed the practice of letting their properties to black people, so that rent-controlled white tenants would feel they had little choice but to leave, enabling the landlords to let out their flats at a higher rate. Panorama reported that, if this didn’t work, Rachman would pay Caribbean immigrant tenants to play deafening music at all times of the day and night. The BBC also reported claims that Rachman hired black hoodlums to intimidate white tenants, or, conversely, white hoodlums to harass black tenants; and if these tactics failed, Rachman would employ thugs with Alsatian dogs to wrench doors off their hinges, remove roof tiles, and rip up floor boards in order to terrify those he wished to evict.

Privately, Rachman’s friends and associates were appalled by the denigration of the generous and kind man they had known. However, wary of having their names similarly tarnished, most were unwilling to speak up in the dead man’s defense. One notable exception was Serge Paplinski, a fellow Pole and Rachman’s righthand man in the property business. Paplinksi gave an extensive interview to the News of the World, another Sunday tabloid, which eventually declined to publish any portion of it because it painted Rachman in a positive light.

The weeklong press mauling of Rachman only abated when, on July 22, the story was bumped by the trial of Stephen Ward, a doctor who was at the center of the Profumo Affair, a scandal involving, among others, two women who’d worked as Soho showgirls, Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies, the government’s war minister, John Profumo (who was alleged to have slept with Keeler), and a Soviet naval attaché named Ivanov. Ward was charged with living on the earnings of prostitution, and the newspapers turned their attention to hounding him. He subsequently committed suicide before the court reached a verdict.

At the time of his death, Stephen Ward’s name, like Rachman’s, had been thoroughly besmirched by the British press. But something else had happened to Rachman’s name: it was turned into a noun, “Rachmanism,” by no less a figure than the Labour Party leader Harold Wilson, who would become prime minister little more than a year later. In a 1963 parliamentary debate on housing, Wilson condemned “the disease of Rachmanism,” and the term soon entered the Oxford English Dictionary with the following definition: “exploitation of slum tenants by unscrupulous landlords from P. Rachman, London landlord of the early 1960s.”

Advertisement

Strangely enough, it was the Profumo Affair that had brought the recently deceased businessman’s name to public attention. As journalists dug into the salacious details of Stephen Ward’s story, they learned that one Peter Rachman had been Ward’s landlord, for the doctor’s agreeable mews house in Marylebone. That Rachman’s portfolio also included a good many “slum” properties in the Notting Hill area of West London, flats that were often rented out to white prostitutes and recently-arrived West Indians, further piqued the press’s interest. And it soon became apparent that Rachman was involved in other ways. He, too, had slept with Keeler, introduced by Ward, and Rice-Davies had been Rachman’s mistress for a time, installed at one of his properties.

As the country waited for Ward’s trial to reveal more of the story, the press sought out Rachman’s tenants and paid those who came forward with tittle-tattle about their former landlord. Unable to defend himself from beyond the grave, Rachman was depicted as a sleazy foreigner and a sexual opportunist, a ruthless man whose only interest lay in turning a profit and whose eagerness to rent to blacks and prostitutes had undermined the lives of decent white people. To cap it all, he was a stateless Jew, who had been denied British citizenship. All of this flowed into the undertow of what was understood by “Rachmanism,” though it was not clear how many of his former tenants would even have remembered him.

*

Perec Rachman was born in Lvov in Poland in 1919, the son of a middle-class dentist. Despite the country’s strong current of anti-Semitism, Rachman was brought up to believe himself a Pole and he tried hard to fit in. Following the Nazi invasion of his homeland, in September 1939, Rachman was captured by the Germans and put to work building an autobahn heading east, toward Russia. He escaped from this forced labor and made it into Soviet-occupied Poland. But there he was arrested by the Soviets and sent to a Siberian labor camp where he suffered great privations, including being forced to eat human excrement. “I never ate German shit,” Rachman is said to have proclaimed. “At least no one can say that I ever ate that.”

After the Germans invaded Russia, in 1941, the USSR entered the war on the side of the Allies. Rachman, along with his fellow Polish prisoners, was then allowed to join the Second Polish Army Corps; he served first in the Middle East and later in Italy. In December 1946, Rachman was transferred to Britain and held in a resettlement camp in Scotland before being moved to Oxfordshire from where, in 1948, he was demobilized. He made his way to London, and there learned that all of his family, including his parents and his brother, had perished in the concentration camps.

This sole survivor, a small chubby man, whose high squeaky voice hampered his wish to project gravitas, nevertheless determined to make something of himself. He began by working at a series of menial jobs in the East End of London, and then in the West End, in Soho, before finally, in 1954, stumbling into the world of property management. He worked first as an estate agent, renting and selling others’ properties, and slowly began to build up a portfolio of his own, buying up run-down row-houses in West London cheaply, and making money by renting them out. Within just three years, Rachman could count himself as a prosperous man. He controlled dozens of substantial properties in Notting Hill and Shepherd’s Bush, and he took to the businessman’s perks of smoking fat cigars and driving a luxury Rolls-Royce.

Rachman had a formula. He would purchase once grand but now shabby townhouses and turn a fast profit by subdividing them into multiple units that he’d rent out as “furnished” dwellings to those who found it otherwise difficult to obtain affordable lodging in London. Tenancies for unfurnished properties had certain protections under the law, but those in furnished accommodation were easily exploited. Having acquired a house, it was a relatively simple business to negotiate with sitting tenants and encourage them to quit their rent-protected properties—or to arrange for their eviction—along with their furniture. Then Rachman would subdivide the house, move in old tables, a few chairs, and some mattresses, and put the rooms or flats back on the rental market as newly furnished.

Advertisement

Rachman’s first tenants in this enterprise were prostitutes, with whom he freely consorted as a friend and client. He was clearly a quirky man, and the war had left him with a phobia of dirt and a fastidious sense of personal hygiene, as well as a potent fear of starvation—so much so that, according to Christine Keeler, he hoarded rolls of twenty pound notes together with a loaf of hard, stale bread under his mattress. But his wartime experiences had also taught him not to be too judgmental—either about people themselves or the means by which they made a living—and so he moved easily in the world of prostitution.

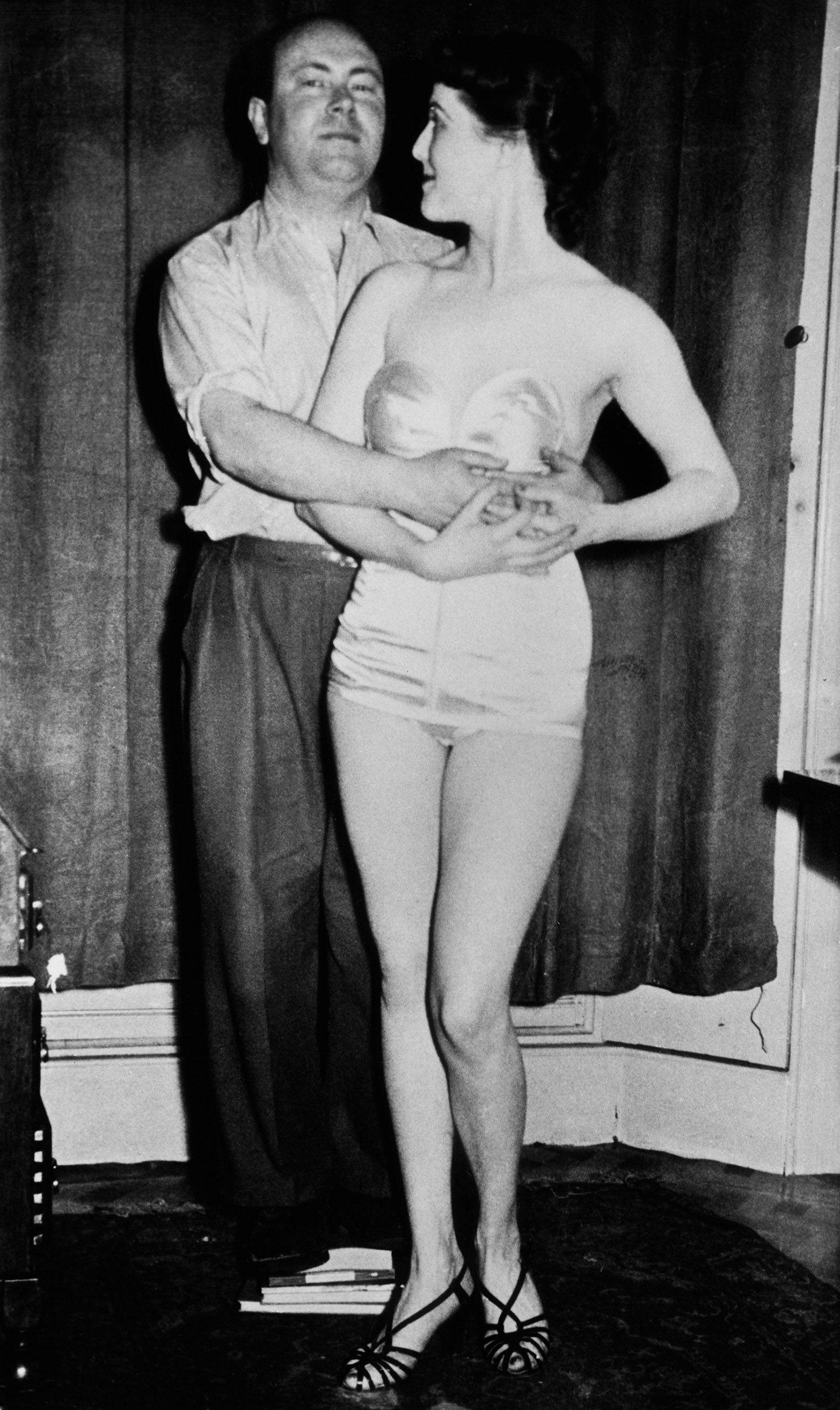

Two girls in a flat “doing business” legally speaking constituted a brothel, but one girl was fine as long as no neighbors made a fuss. Rachman’s girls paid him their official rent, and then handed over additional cash in payment for this consideration, which allowed them to work more safely off the streets. Although Rachman certainly had sex with some of his “girls”—though, according to his biographer, Shirley Green, never against their will, nor in lieu of rent—he was unsentimental about it. Mandy Rice-Davis claimed, “Sex was not a passion with him, but something functional like drinking a glass of water.” This chubby teetotaler was evidently a strange fish, but those who crossed his path almost invariably found him an uncommonly polite, if somewhat shy man.

The newspaper accounts made it clear that Rachman not only rented to prostitutes, but also welcomed “coloured” tenants, thereby ruining neighborhoods. Between 1948 and 1962, some 250,000 West Indians arrived in Britain from the Caribbean, and the most pressing problem facing them was housing. The Trinidadian writer, Samuel Selvon, who settled in London in 1950, constructed an entire novel, The Housing Lark (1965), around this vexing issue. Until the Race Relations Act of 1965, it was perfectly legal for landlords to stipulate, both in person and in written advertisements, that “No Coloureds” were permitted as tenants. And even if these prospective tenants were willing and able to pay ludicrously high rents, many landlords still preferred not to rent to black people. Rachman, however, saw no reason to discriminate against the newcomers. In the late nineteen-fifties, shortly before the Empire News merged with its more popular Sunday competitor, the News of the World, Rachman gave an interview to the soon-to-be defunct newspaper.

“The government does nothing to house these West Indians when they come over here. Somebody must,” he said. “That’s why they come to me. I find coloured people good tenants… I take people as they come. Mind you, some white people do object to the coloured people when they move in. They don’t always like the way they play jazz records up to 1:00 AM and always loudly.”

To be sure, an unfurnished room that might be rented at £1 a week to a rent-controlled tenant could then, in racially intolerant Britain, be rented at £6 a week to a West Indian newcomer as furnished accommodation. Rachman certainly turned a handsome profit renting to “coloureds,” but he could never be accused of slamming a door in a West Indian face because of racial prejudice.

When the newspaper campaign of vilification against Rachman began in 1963, it was very difficult for journalists to find any West Indian former tenant who had a bad word to say about him. In fact, this so-called slum landlord was regarded by many in the newly-arrived immigrant community as something of a godsend. Speaking about Rachman a few years after his death, a West Indian social worker whose job during the 1950s had been to meet West Indians off the boat train, was clear in his assessment of him: “To the West Indian he was a saviour and people still have a lot of respect for him.”

Long before his death in 1962, Rachman had begun moving out of the business and was seeking to establish himself in the more lucrative, and respectable realm of property development. He had once controlled as many as a hundred houses in West London, but from 1958 he began to sell or hand over control of most of them; by the time he died, he owned only a dozen or so. An irony of his decision was that among the new generation of “slum landlords” were university graduates like the future Conservative politician Michael Heseltine, who went on to parlay his profits from the insalubrious world of the Notting Hill housing market into a magazine publishing empire. In his bid for respectability, Rachman borrowed heavily to fund a project that involved purchasing a large industrial site in the Midlands that he hoped would bring him greater wealth, and prestige. The pressure of this new deal caused him considerable stress as it stretched his finances to breaking point.

By early 1963, thanks to intense media scrutiny, it was clear that John Profumo, the cabinet minister, was in serious trouble. On June 5, he stood up in Parliament, confessed to having misled the House over the nature of his relationship with Christine Keeler, and he immediately resigned. This was a scalp for the press, but newspapers were still unable to tackle the Profumo Affair directly for fear of legal repercussions under Britain’s strict libel laws. There was also the additional problem that the case against Dr. Stephen Ward was sub judice, and almost nothing could be reported in connection with him until his trial began. Once the press unearthed a link between Profumo and Rachman—by way of Keeler and Rice-Davies—it became clear how they could fill their pages while they waited for things to develop higher up the social and political ladder. Both women were more than happy to take money for interviews in which they recalled the details of their relationships with the recently deceased landlord. They went to town on the Penny Dreadful details of slums and sexual immorality, “coloured” immigrants, gangsterism, and general squalor and profiteering.

This unseemly “checkbook journalism” of June and July 1963 was replete with frequently absurd moral indignation about Rachman’s character. On July 9, Mrs. Ian Fleming, Ann, wife of the Bond author, was quoted in the Evening Standard claiming to remember once seeing Rachman: “I was reminded that I had seen him driving a Rolls-Bentley [sic], and he slowed down to greet a friend. I shouted, ‘It’s one of Ian’s villains—straight out of Bond.’ It was certainly one of the most evil faces I have ever seen.” Those such as Serge Paplinski who sought out the press in order to tell a different story were ignored. Among London’s Caribbean community, Rachman is remembered quite differently from the way the dictionary suggests we should think about him. Those of the “Windrush Generation” regard Rachman as a man who made it possible for many of them to get a roof over their heads—at a price, yes, but at a time when the majority of landlords were turning them away. Rachman enabled countless immigrants to begin to edge their way forward and into British society. As the Empire News told its readers: “The coloured people tell each other: ‘Go see Rachman, man.’”

Stephen Ward was undoubtedly a victim of the Profumo scandal, but so, too, was Rachman. Newspaper interest in him was incidental, and temporary, but the damage has been permanent. Rachman belonged to a world that polite society (including those among the political elite) did not approve of, though it pruriently enjoyed reading about it. But that coinage, Rachmanism, is now inscribed in the English language as shorthand for rapacious, unscrupulous landlordism. Today, in an age when both the Labour and Conservative parties have been roiled by credible charges of anti-Semitism among their members, we might reflect on how a Holocaust survivor, Polish patriot, and ex-serviceman was transformed by Britain’s popular press of the 1960s into a veritable Bond villain, a fantastical schemer and exploiter. Rachman was hardly a Rothschild, yet his name is still invoked as a byword for sordid capitalist exploitation. How much has changed?

Given the evidence of today’s politics, with Britain’s chief rabbi’s intervention in the recent general election claiming that the Labour leader was not fit to be prime minister, and the current prime minister coming under scrutiny for supposedly anti-Semitic descriptions of a Jewish character in his 2004 novel Seventy-Two Virgins, one might suggest, “Not enough.” On July 26, 1963, the cover of the satirical magazine Private Eye featured a large photograph of a smiling, coquettish Mandy Rice-Davies with the caption: “Do you mind? If it wasn’t for me you couldn’t have cared less about Rachman.”