The sound of the sea, by turns serene and smashing, washed faintly over the fourth-floor gallery of New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art this past summer, where fifteen new paintings and an installation by the British artist Lubaina Himid were on display in an exhibition called “Works from Underneath.” Curated by Natalie Bell and accompanied by a pair of sound collages by Magda Stawarska-Beavan, the show was a slow-rolling wave of meditations on labor and whether toiling on our own terms can subvert a history of exploitation. Each work, a kind of odyssey through the precarious conditions of migration, revealed tangled and fraught histories of the work black people have done to build empire.

“Work from Underneath” was Himid’s first solo museum show in the United States, but she has been making art for forty years. As a member of the Blk Art Group, she was a leader of the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s and 1990s, through which artists of color like Himid, Rasheed Araeen, Sonia Boyce, and the Black Audio Film Collective—a group of multimedia artists and filmmakers that included John Akomfrah and Lina Gopaul—challenged the predominantly white art establishment’s exclusionary practices with antiracist discourse and feminist critique, and expanded the definition of British art to include African and Asian diasporic experience. Early on, Himid organized a quartet of exhibitions to ensure that the work of British female artists of color was shown in museums and galleries (including “Five Black Women” at the Africa Centre, London in 1983 and “The Thin Black Line” at the Institute for Contemporary Arts, London, in 1985). Throughout her career as an artist, curator, and educator (she is a professor of contemporary art at the University of Central Lancashire), she has continued this necessary work of inclusion.

Meanwhile, her own work received little attention in the mainstream art world—until recently. Himid satirized the London art scene and the politics of the day in A Fashionable Marriage (1986), a marvelous theatrical tableau of bawdy, larger-than-life-size painted plywood cutouts that included collaged images based on the figures in William Hogarth’s own, earlier, sendup of British society in The Toilette, from his Marriage A-la-Mode series (1743–1745). Originally exhibited in 1986, A Fashionable Marriage was more recently on view at the Tate Liverpool in 2014, and at the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull in 2017, when Himid became the first black woman (and oldest artist, at the age of sixty-three) to be awarded the prestigious Turner Prize. Since then, she has been named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire “for services to art,” and has been granted show after show at European institutions, including the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art and Tate Britain, as well as at the New Museum in New York.

The New Museum’s recent exhibition focused exclusively on Himid’s most recent work. At the center was her installation Old Boat/New Money (2019), for which she arranged thirty-two tall, thin planks of wood in an undulating row along a white wall, leaning precariously on their tips as though they might collapse. Each plank was painted a different tint of gray, from slate to taupe, and accented at the base with depictions of cowry shells, a form of currency used during the transatlantic slave trade. Together, the planks suggested the design of old wooden ships, as well as the black bodies that were once bound together in the hull of those vessels and sold into chattel slavery. The timber cast long, dark shadows against the wall. History has a way of announcing itself. In the exhibition catalog, Himid explains that what she is trying to do with Old Boat/New Money—and perhaps all her new work—“is get to the heart of a kind of collective memory, to get to the center of something that’s falling apart and fading and coming back into view in the way that memory and history do.”

The black figure as commodity is a constant concern in her œuvre, where black expression, as a way to determine the value of black life, is tied to black labor, both creative and physical, forced and freed. In an earlier work, Naming the Money (2004), Himid created an installation of one hundred life-size painted cutouts of enslaved black colonial figures—including drummers, toy makers, ceramicists, herbalists, and viola da gamba players—to whom she gave name and voice to enable their being documented and remembered in ways canonical history has failed to. “Every person in the installation is trying to tell you something,” Himid has written. “Each has a voice that can be heard via the soundtrack playing in the gallery space or as text on an invoice collaged to his/her back.” The words on the back of one figure proclaim:

Advertisement

My name is Nakati

They call me John

I used to make masks

Now my shoes are worn by kings

But I have the colour

“Works from Underneath” also included two large paintings, Six Tailors (2019) and Three Architects (2019), both of which are concerned with illuminating the lessons of labor in black history. In each of them, Himid has rendered a capricious sea—one of her signature motifs—in gray, visible through the windows of the depicted workspaces. Indoors, artisans are gathered around their workstations, in the midst of collectively designing garments and buildings. The colorful textiles that the figures are assembling in Six Tailors, and the ones they peacock, could easily be mistaken for batik styles created by the emerging Nigerian label Kenneth Ize, which employs local female weavers to construct richly patterned looks from vibrant aso oke and Akwete textiles. Himid’s mother was a textile designer; the making of clothing in her paintings conveys self-possession, the stain of colonialism, and the acknowledgment that often immigrants—and, before them, the enslaved—carry little more than their knowledge of home with them to foreign lands, where the only certainty is their unfamiliarity. They “work from underneath” with the hope of gaining status and station, and perhaps to reclaim a part of themselves lost in transit.

Both Six Tailors and Three Architects continue Himid’s decades-long injunction that we interrogate the legacies of black labor, and the ways it’s recognized and remembered. These paintings signal a continuing need to develop new protective infrastructures where we can, in Himid’s words, “invent new rules by which to live.” In her paintings and installations, Himid has long explored the theme of labor as a way to achieve self-determination. But as I stood in the main room of the exhibition, I wondered, why must we work to communicate worth either to ourselves or to society?

The black body in art has rarely been seen still, without a job, in protest of nothing. Toni Morrison famously observed, “You are not the work you do; you are the person you are.” Seeing Himid’s black figures labor as a way for her to reclaim them for us, I wanted to know: Who were these figures to themselves and one another? And what do their own definitions of themselves mean in their struggle for personhood? Through labor we can develop a sense of self through accomplishment, but the history of the laborer who presents herself in Himid’s work also suggest something else entirely: through the act of labor, we lose a way to separate who we are from the value of what we might contribute to the market.

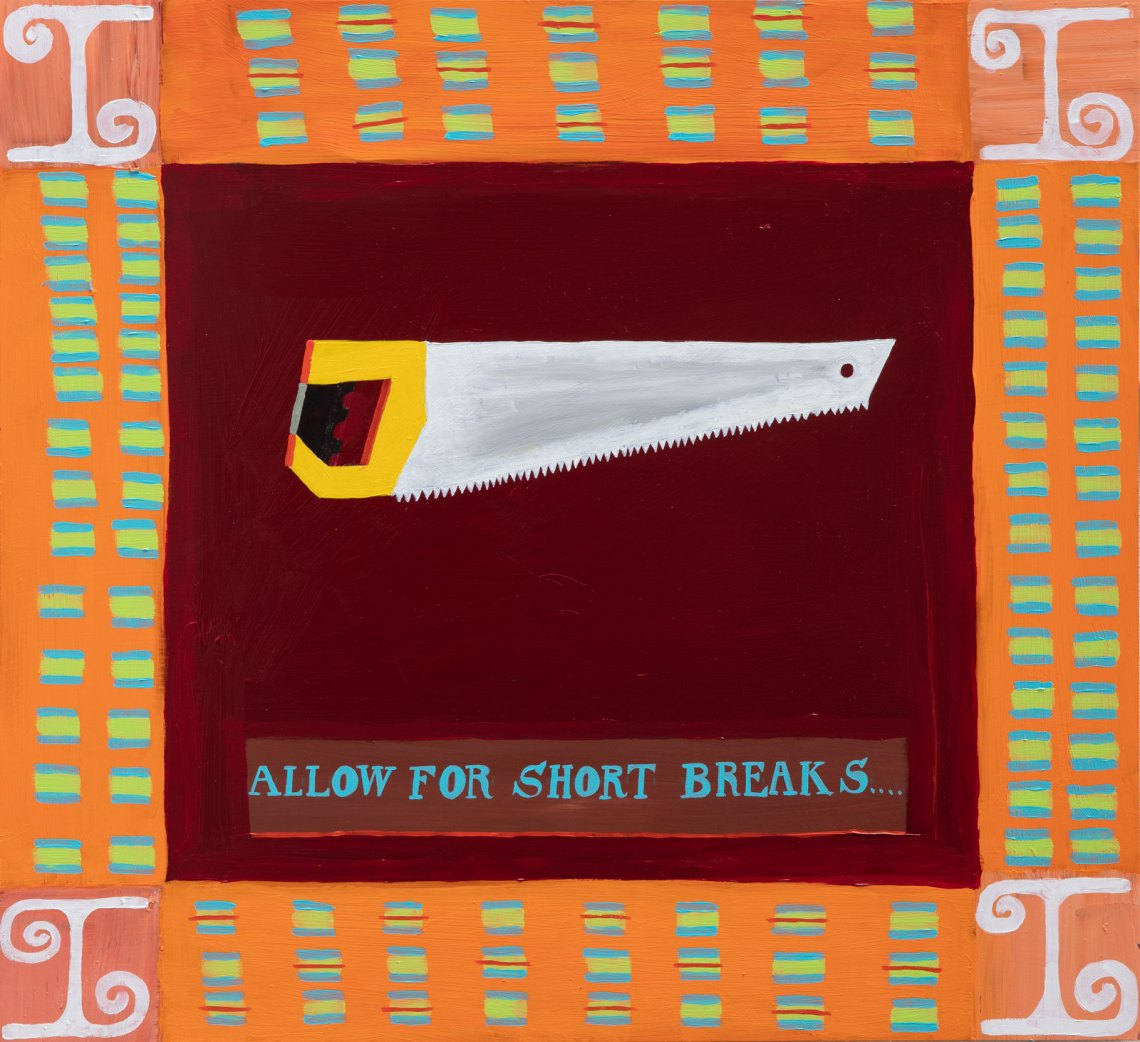

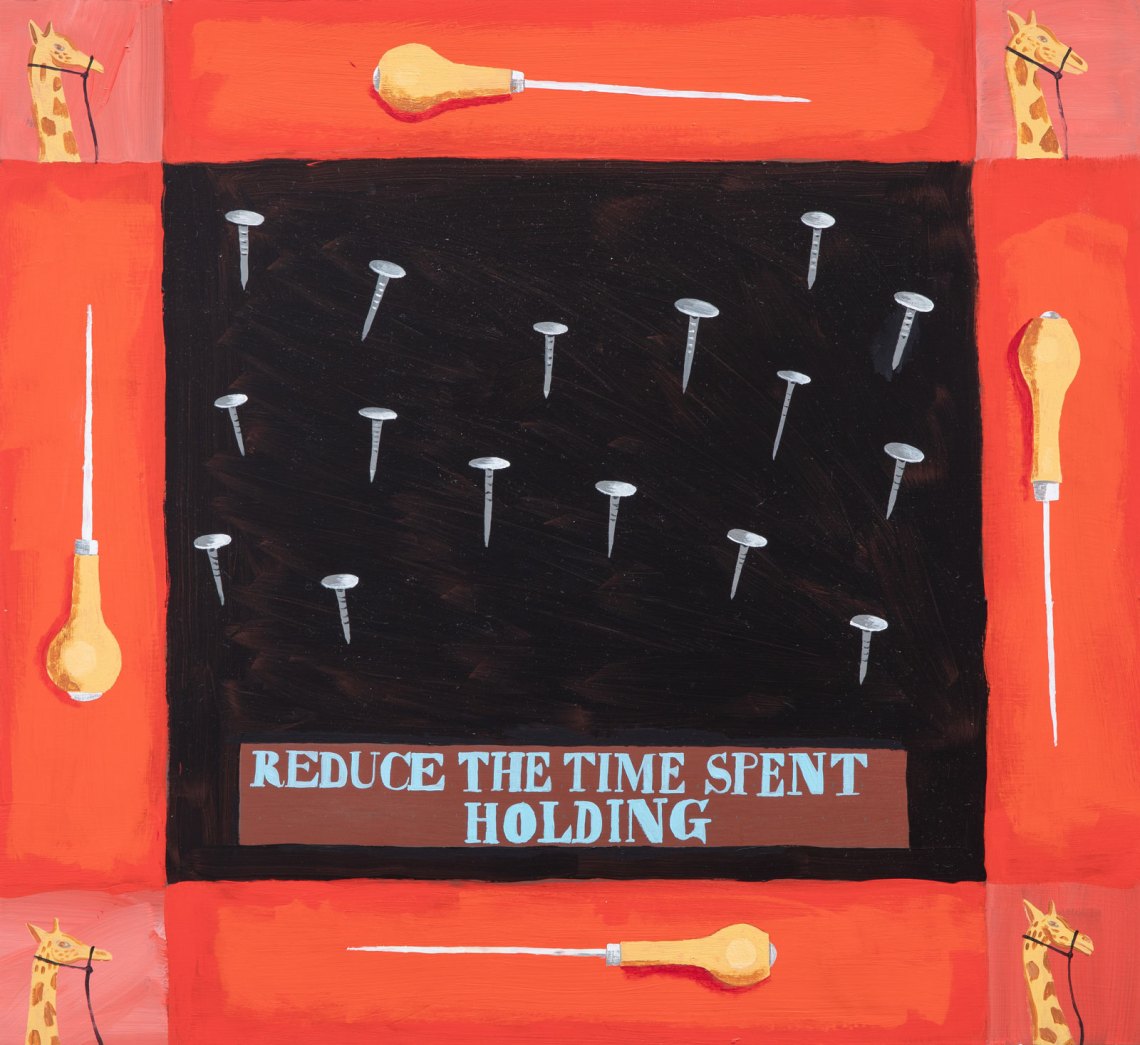

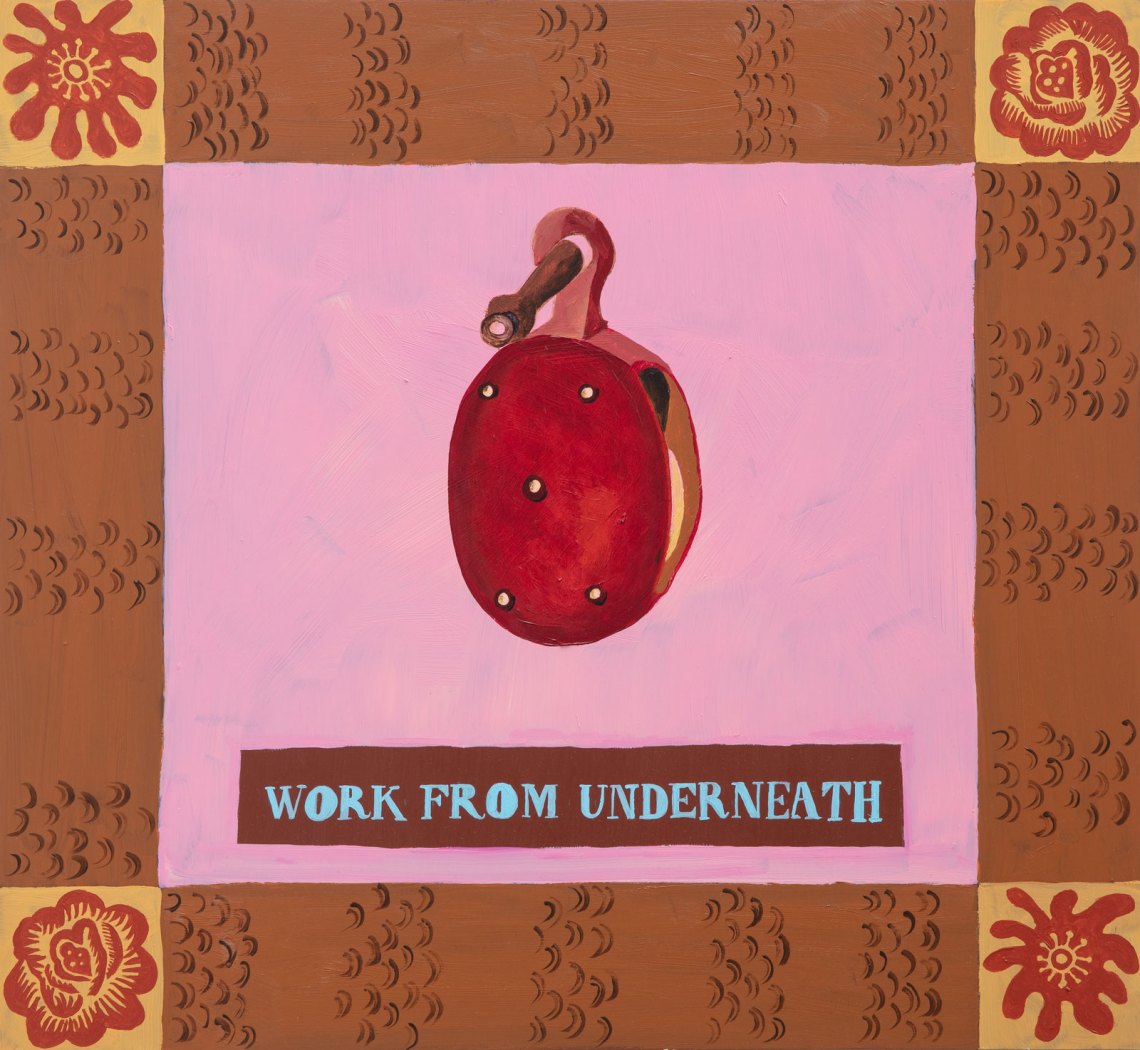

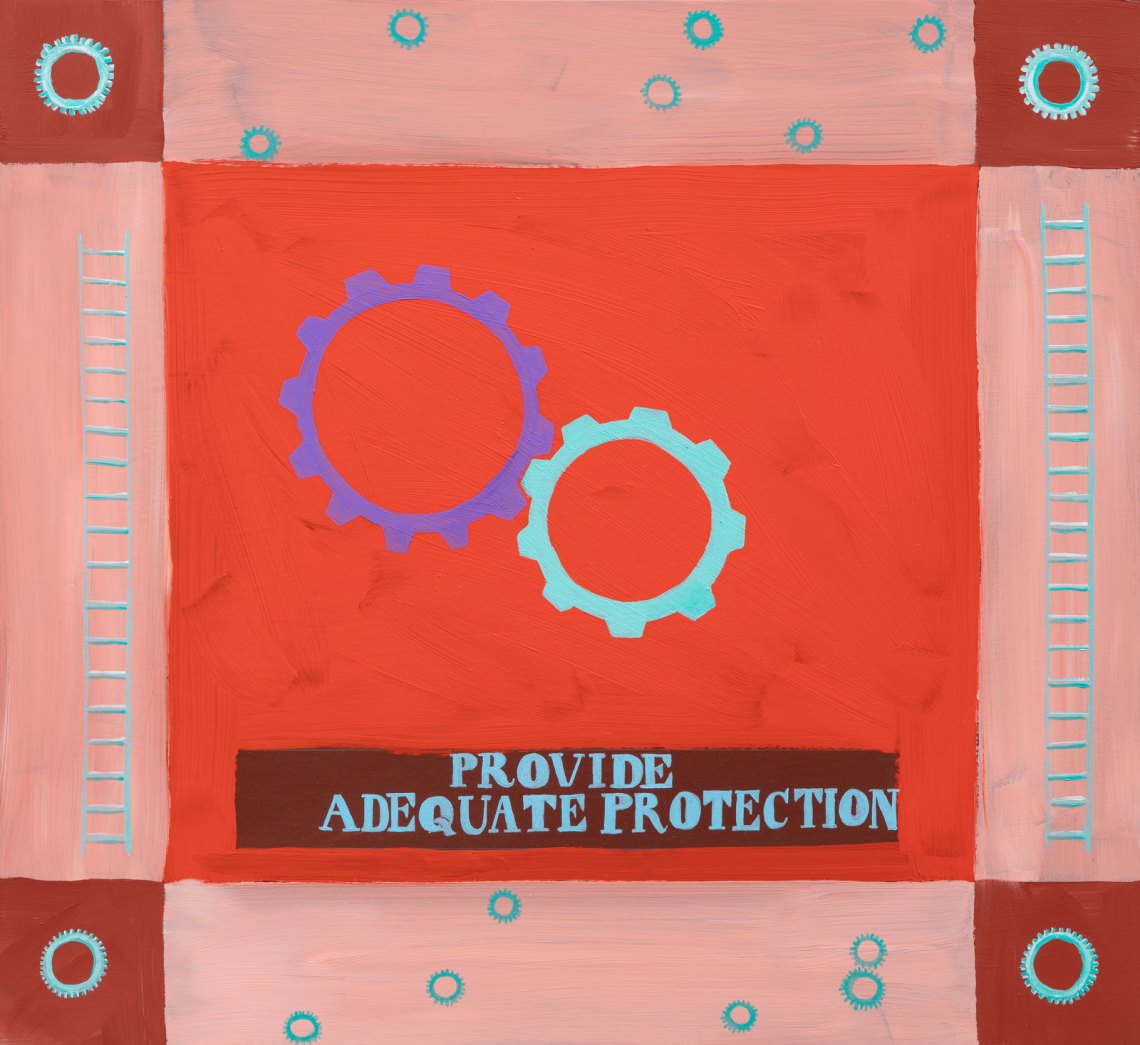

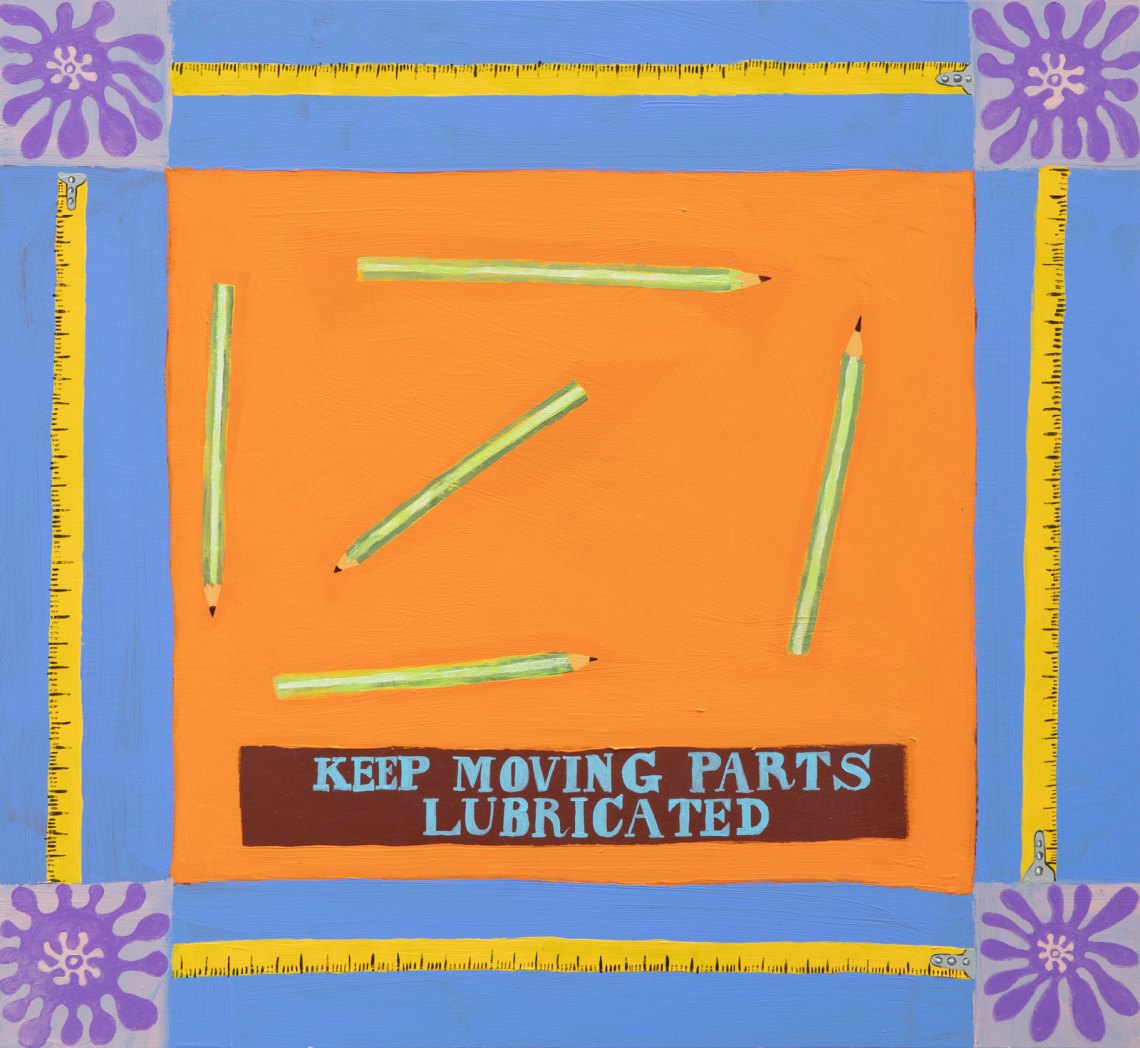

On a separate wall at the New Museum, Himid hung a series of nine small works called Metal Handkerchief (2019), depicting the tools of the manual laborer—a hammer, a saw, a hinge, a set of nails—on multicolored metal sheets, accompanied by phrases she found in British technical manuals and health and safety guides: “give warning of undue strains,” “reduce the time spent holding,” “allow for short breaks,” “provide adequate protection.” The texts paired with the hardware appear at once as humorous abstractions, working-class aphorisms, and a litany for survival. For Himid, the works provide a balm for this moment: “I’m interested in how you can extract something very beautiful from something that needs to have a very practical clarity in order for people to remember it,” she said in a conversation with curator Natalie Bell. “It’s a bit like understanding how rich and varied gray can be…It’s to take something that seems to have no poetry and make poetry out of it, and then to start again.”

Himid’s use of grayscale in her work communicates a deliberate placelessness. Two of the walls of the airy gallery were painted in a dark gunmetal shade, which filled the room with a feeling of disillusionment. When gray appears in her work—whether in her oceans, or in the far-left figure in Six Tailors, or in the shirt of another of the tailors, or in the hammer, saw, and nails of the Metal Handkerchief series—it establishes mood and the psychological fatigue of her figures. They seem to have worked to the point of exhaustion in order to claim identity and memory in an insecure and forgetful present. The poet and scholar Fred Moten put it this way in an essay in the exhibition catalog: “The world always forgets what earth and air and water won’t forget.” In Himid’s work, the beautiful and ugly parts of heritage are inescapable. Remembering is the necessary work of justice, and Himid both roots her subjects in a rich past, alluded to in vibrant ochres, siennas, and cyans, while reminding us of their complicated inheritance with her sly use of grays.

Advertisement

Himid immigrated to England from Zanzibar, Tanzania, with her mother in 1954, when she was four months old. She developed an affinity for the leaden hue as a child. On visits to London’s museums she saw that color in the art of British modernists like Lucian Freud and noticed it in the streets because, as she told Bell, “gray is the color of the country”:

The sky is very often gray, the sea is gray—there are very few coastal places in Britain where the sea is blue, and very few days of the year when the sky is blue. I have tried, in my discussions with myself, to understand what being a British painter means in terms of color, and it’s quite often that mastery of gray… Over the years, I’ve understood how I can get a lot of color into gray, and that’s what I’m trying to do here. I’m trying to make an incredibly colorful painting, but in gray. It’s a battle to keep myself from painting orange stripes down the side of each plank. It’s also a challenge to myself: Can an African painter paint like a Northern European one?

When I noticed gray in Himid’s paintings, I thought not of white European painters, but of the postwar Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava. Where Himid strategically uses gray to bring narrative and theatricality to her art, DeCarava used it to communicate emotional and formal power in his black-and-white photographs of mundane street scenes of uptown life, as well as in his portraits of jazz musicians, recently on view in “Light Break” and “the sound i saw,” a pair of exhibitions at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York. In Elvin Jones (1961), DeCarava’s portrait of the post-bop-era drummer, Jones is hard to see, but his artistry is visible. Only his head and torso are pictured, but it is clear that he has worked himself into a vigorous sweat. Ripples of gray record the musical vibration as fuzziness in the image, making visible the sound he made, a visual recording of his gift. Considering the image now, it is not only a representation of how Jones and his contemporaries, like DeCarava and the everyday people the artist captured, were eventually lost to history without concerted efforts of preservation; it also suggests the craning of the neck that is required to really hold him in your mind, protecting the sight of a black man making his art, despite it all, captured by DeCarava’s attentive eye.

In addition to Himid’s recent show at the New Museum, her sculpture installation Five Conversations (2019), a set of life-size portraits of women painted on reclaimed wooden doors, can be seen at the High Line through March 2020. Notwithstanding these displays of her latest work, what Himid deserves is a major retrospective that fully recognizes her not solely as an artist but also as a “political strategist” (her preferred label) who blew open the gates of British art to make space for herself as well as her forebears, peers, and those who will come next.

“Lubaina Himid: Work from Underneath” was at the New Museum in New York City from June 26 through October 6, 2019. Five Conversations will be on view at the High Line through March 2020.