The Haddad family have moved since I first visited them in Jordan last year in 2018: they’re still living in the same building in East Amman, but this time ten-year-old Saber led me past the door of the apartment I knew and up to the next floor. It was cosier, because it was smaller, and therefore cheaper—150 Jordanian dinars a month (about $210) rather than 250 dinars ($350) for the more spacious floor below. Spacious, yes, but the old one felt more desolate as a result. The furniture seemed sparse, if, on occasion, innovative. The baby’s cradle was a plastic vegetable crate, lined with blankets, hung from a water pipe in the ceiling, free to swing.

The situation was very different when the family arrived from Syria in 2013, when Saber was not yet four. He arrived with his mother, Noor, and father, Omar, in the Jordanian capital, where they joined Noor’s parents and four younger siblings who were already living there with another Syrian family; all of them, 15 in total, sharing just four bedrooms. The extended family is now dispersed according to the lottery that is the UN refugee resettlement program: Noor’s parents and three youngest siblings are in the UK, granted asylum in 2017, her older brother is in Saudi Arabia, but she herself did not get allocated to any other country, along with hundreds of thousands of other refugees in Jordan.

One of Noor’s sisters, Nadine, also remained in Amman, married to a Syrian whose family is even more far-flung—her husband, Ahmad, has one brother in America and another in Australia. (Ahmad himself was in the process of applying to the United States for asylum when Donald Trump was inaugurated and the US refugee resettlement program was abruptly suspended, and subsequently drastically curtailed.) As their original, overcrowded apartment gradually emptied over time, it became unaffordable for Noor’s immediate family, which has to survive on a single income.

Those family members still in Jordan were all here to greet me, and Omar and Ahmad had taken precious time off work to talk, hoping that any article I would write might perhaps change their predicament, maybe even help get them all to the West to rejoin their other family members. This was a version of the first conversation I always have with them: they always show me their UN papers, proving their status as refugees. And I always explain that I’m not a lawyer and have no influence over refugee visas, feeling impotent in the face of their desperation. In the case of my country, the UK, the government’s position has in fact hardened—creating a “hostile environment” is its own description of the new policy’s intention—to all immigration. Doors that should be open to them everywhere have closed.

Syrians do not have an automatic right to work in Jordan, although there are some unrestricted sectors. Both men have taken advantage of this: Omar works in a laundry, Ahmad at a dry-cleaner’s. They both work fourteen or fifteen hours a day, six days a week. They each receive a basic salary of 300 dinars ($420) per month, which could get up to a maximum of 400 dinars ($560) with even more overtime. After rent, electricity, and water, an average month’s work leaves about a hundred dinars ($140) for everything else, from food to medicine, in a country where a Starbucks coffee comes in at four dinars (almost six dollars) or more. Over in affluent West Amman, that monthly budget for feeding a family of five would just about cover dinner for two at some places.

“Our house is just not a healthy place for our kids,” Ahmad told me. “Especially in winter, when it’s cold as well as damp. They have trouble breathing, especially at night.” The medicines for the children’s asthma alone cost about fifteen dinars ($20) a month. (Some medicines are available from international organizations such as Caritas or the UN, but the ones these children need happen not to be covered under either of those programs.) Ahmad’s mother, Bushra, also has medical problems, including diabetes, which they can’t afford to treat at all. With their means, even the most ordinary things are out of reach—even entry to a public park in Amman costs a dinar per person, an unthinkable expense.

They are not ungrateful to Jordan. “It is safe, unlike Iraq, and it works: there are no problems with electricity or water, like in Lebanon,” said Noor. “It is a good country, but you need money, money for everything.” And because of that, “It’s like living in one big prison.” Noor broke off to talk nostalgically of the old days in Syria—of Friday family picnics. “Our friends mostly live too far away to walk to,” she added, sadly, “and we can’t afford a taxi… The phone is the only thing that gives me hope in life, because it lets me talk to my family.”

Advertisement

*

About 6.7 million Syrians have left their country to escape the violence of the civil war. Some have made it to Europe—between 2014 and 2016, nearly a million asylum-seekers, mostly Syrian, were accepted by Germany alone. But Turkey and Lebanon have received an estimated 3.6 million and 1.5 million respectively. Although the part Jordan has played as a war refugee destination has been less publicized, its contribution among Syria’s Arab neighbors has been extremely significant. Some 654,692 Syrian refugees have been registered in Jordan since 2012, after the beginning of the conflict in Syria. But the actual number, including unregistered refugees, is believed to be higher; some estimates put it at 1.3 million. This in a country of just over 10 million people but an economy worth little more than $40 billion a year—roughly the same GDP as a sparsely populated, rural US state like Montana or Wyoming.

According to the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), “Jordan is one of the countries most affected by the Syria crisis, hosting the second highest share of refugees per capita in the world.” The country is familiar with the task from its history of acting as a haven for waves of Palestinian refugees, from 1948 onward, but today, already reliant on international aid, and water-deficient, Jordan has struggled to provide services to so many extra people. The public schools run a split-shift system, whereby they teach different sets of children in mornings and afternoons, meaning both longer days for teachers and less education for children. Prices have gone up and up, leading to widespread economic discontent, the very issue that sparked the Arab Spring across the region in 2011.

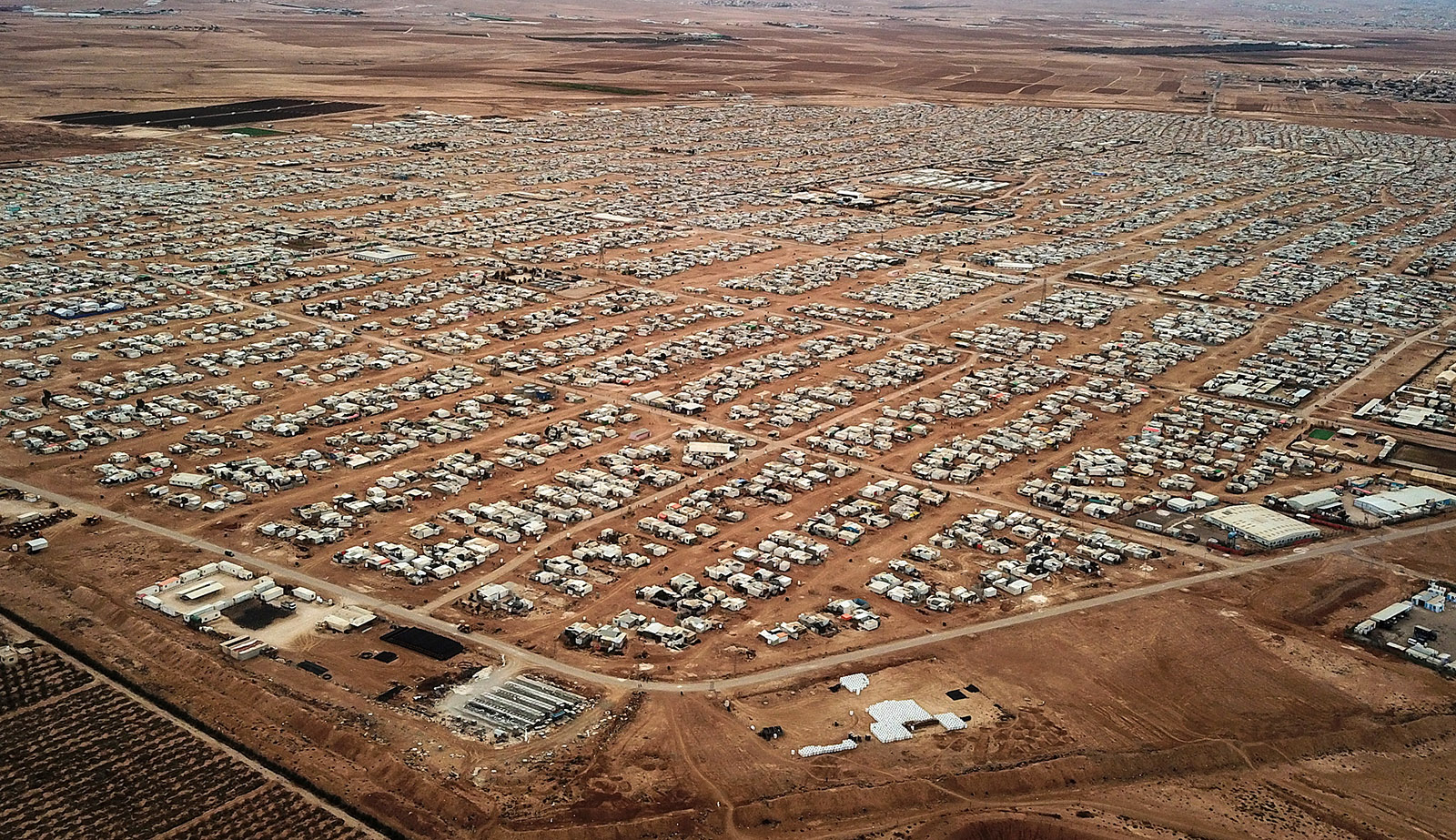

Many of the registered Syrian refugees are living in huge camps: Zaatari, close to the Syrian border in the north, is said to be the largest Syrian refugee camp in the world, with 76,602 inhabitants; just over an hour’s drive away is Azraq, home to another 35,752. These numbers translate into row upon row of regulation white tents, stretching as far as the eye can see; the camps are as big as small towns, grouped into “villages” in order to foster communities. After almost nine years of conflict in Syria, and given the attitudes that prevail among refugees about returning to live under Assad again, it is widely accepted throughout the aid community and diplomatic circles that this is long-term work.

But there are Syrians not just living in the camps, or even, like Noor and Nadine, in the so-called host communities of the cities and towns. There are other groups of Syrians in Jordan who have slipped through the gaps of every system: the UN, government, or charity. These displaced people live a nomadic existence in clutches of tents, moving en masse to follow the seasonal, mostly agricultural, work around Jordan. In the sanitizing jargon of international nongovernmental organizations, they live in what are known as “Informal Tented Settlements,” or ITSs. Because these people all travel together, they are close-knit, existing as a self-contained community often formed of extended kinship groups. Resistant to outside interference, they in turn go unnoticed by many Jordanians.

In the hot summer months, many of these migrant workers move their tents north, with a concentration around the capital, Amman. Some of their tents huddle among the crops along the road to Amman’s airport, in the shadow of a giant IKEA store where Jordan’s elite shop for their homes. I was among a party of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) researchers that went to meet one such group of itinerant workers in July, when there is an abundance of the small cucumbers of the region, which are eaten both fresh and pickled. A tray of them was brought into the tent where the research team was congregating. It felt wrong to take food from people who had so little, but the children, aged between ten and eighteen, trickling in from working in the fields were glad to share what they had: “It’s all we eat,” said one of them, “we’re bored of them.” They were, in fact, delicious and refreshing on a hot day in an even hotter tent, where the flies were thick and bothersome, though seemingly not to the children who do not even bat them away.

UNICEF is the one international agency that has made inroads into this migrant community, and it partners with a local charity named Mateen. In 2011, UNICEF Jordan had under twenty people in its Amman office, working on social issues with a budget of $2 million. With the influx of Syrian refugees, the office saw a surge of staff seconded from other UNICEF offices—people like Robert Jenkins, from the headquarters in New York.

Advertisement

“It was one of our quickest ever expansions, due to the scale of the humanitarian crisis,” he told me a few months ago. After his initial, temporary deployment in 2013, he has since become the agency’s country director, today managing more than two hundred staff, with a budget to match, which is among UNICEF’s largest country offices. And as UNICEF Jordan got to work, it created programs to address the needs of some of the most vulnerable and traumatized children the agency had encountered.

“I don’t go to school,” eleven-year-old Ibrahim told me. “Think of the last time you went to school—was it in Syria?” I asked. “No,” replied the boy, “I’ve never been to school.” He was quick to resist the judgment he felt was coming: “I want to! I want to learn to read, to learn English, to learn everything!” he said. “But none of my family go to school, we can’t.”

The particular issue of how to access the children in these communities, who are often not at school and move around the country with the seasons, had proved challenging for the UNHCR. But UNICEF found a way in, through the members of the informal camps themselves. In each community, they identified a local inhabitant to take responsibility for one extra tent, which they provided and filled with materials to support education and recreation. When the camp packs up to move to another governorate, the manager simply packs up this tent, too, and moves it with his own. The walls pinned with pictures from the children and educational posters, the materials provided by UNICEF carefully looked after—all are packed and go with the group. It might seem an unstable and unpredictable way of life to children who live in houses, but these children feel the opposite: there is safety in owning a tent: “I know that wherever we go, we will always have a home,” one twelve-year-old Syrian girl said to me.

But it’s not just Syrians who live in this tented community abutting IKEA. Pakistani children, too, are coming in from the fields. Some of the Syrian girls are themselves dressed in colorful Pakistani dresses, and the Pakistani children speak Arabic with a Syrian accent. Such solidarity amid poverty is the positive side of social life in these tight-knit communities, where refugee families relax the bonds of kinship enough to incorporate others. But their overwhelming exclusion and marginality from mainstream Jordanian society has other consequences.

In another group I met, there was a sixteen-year-old, Rania, with a baby. She had a toddler she’d left in her family’s tent, she told me, and was pregnant again. I calculated that she must have been married at age twelve and pregnant immediately. This is a very difficult issue for any outsider to address: child marriage is common, relieving the girl’s family of the need to provide for her, and legal oversight of these itinerant groups is effectively nonexistent. This girl seemed accepting of her situation—or perhaps, unlike Ibrahim, had little sense of entitlement to the education she’d missed.

When it came time to leave, a ten-year-old girl named Zahra came up to me, holding a piece of paper that read: “I live without a soul.”

*

Yet here is the future of Syria: the children in these tented migrant communities, in the big refugee camps, and among the host communities of Jordan; and then all those spread across the globe, and those remaining in Syria, of which another estimated 6.2 million have lost their homes and been displaced. In total, more than half the population of Syria has been displaced, either inside or outside the country’s borders. Too many of them are growing up without enough education, support, or even food.

But even in this constrained present, the parents’ hopes are invested in the future of their children. They want their children to study, maybe go to university, get professional qualifications, but there is a haziness about their ambitions for the next generation. It’s like getting to the West: a dream, perhaps a mirage.

Back in East Amman, the men of the Haddad family were preparing to leave, needing to get back to work: every dinar, every hour, counts; they were not even staying for the lunch Noor had prepared—kibbeh (patties made of ground meat with bulgur wheat, onions, and spices). I asked if I could take photos before the men left. “Of course, why not?” came the reply, but then I explained it was for the article and there was instant panic. “No. No, that’s not safe,” said Ahmad. He told me I could publish their photos only if I said nothing about their attitudes to the situation in Syria or about their views on Bashar al-Assad. All of them still have family in Syria, in government-controlled areas, and fear reprisals.

They fled not only the violence of the conflict but also the threat, for any male over the age of eighteen, of forced conscription into the army. Nadine said that she was already wanted for questioning by the Mukhabarat over her refusal to give a television interview in which she was told to lie and say there was no violence in the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta, her home, at a time when missiles were raining down every day. She took flight that same day, hiding first in a family home in Damascus before they all fled for the safety of Jordan.

Putting my camera aside, I asked if they would ever return to Syria. “No. Never while Bashar al-Assad is in power,” said Omar. Indeed, there is so little to go back to: the family home was turned to rubble in the fighting, and other parts of the family have scattered. “There is nothing for us there,” Noor said, mournfully. “My father worked in Saudi Arabia for eighteen years to pay for that house, and nothing to show for it.”

“We would need to see if anything really changes, if the injustice is really gone,” said Nadine. “Without justice, you cannot live.”

Some names have been changed to protect the privacy and personal security of the refugees concerned.