Merce Cunningham did not like being photographed. Nor was he especially interested in looking at photographs of himself, let alone having photographers intrude while he worked. When I asked him in the mid-1990s for feedback on near-final galleys of David Vaughan’s book Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years, which I was editing for Aperture, Cunningham’s only response was: “Do there have to be so many pictures of me?” Unlike Martha Graham, in whose company Cunningham danced early on, and who collaborated frequently with the photographer Barbara Morgan, Cunningham evaded the camera lens.

This is one reason why Merce Cunningham: Redux, James Klosty’s exceptional collection of over 270 photographs of Cunningham, as well as of the dancers, composers, and visual artists who worked with him, is such a stunning accomplishment. Released the year of Cunningham’s centennial, this reimagined, expanded, large-format iteration of Klosty’s original 1975 Merce Cunningham has been vibrantly redesigned by Yolanda Cuomo and printed in rich duotones by Meridian. Perhaps as striking as the individual photographs themselves is how generously, experienced as a whole, they share the daily life and work of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) during the late 1960s and early 1970s, one of the most fertile periods in its near-sixty-year history.

Performance photographs are rarely thought of as having the interpretive, authorial voice of powerful reportage, portraiture, or other photographic genres. They are often deemed important only as a historical record of another artist’s work, work that is by nature ephemeral. But this is short-sighted. An insightful photographer like Klosty who has viewed the same dance repeatedly, is able to impart a sense of the piece, to translate its very essence into still images, through the phrases he chooses to capture, and the way he chooses to render them. Ultimately, the staying power of any photographic project depends on the photographer’s vision, persistence, and ability to portray the subject with clarity, integrity, and ingenuity. Klosty achieved all three when, over the course of five years, and with unprecedented access, he photographed not just the performances of the Merce Cunningham Company, but also the more intimate, spontaneous, and sometimes goofy moments shared among the dancers and other collaborating artists offstage.

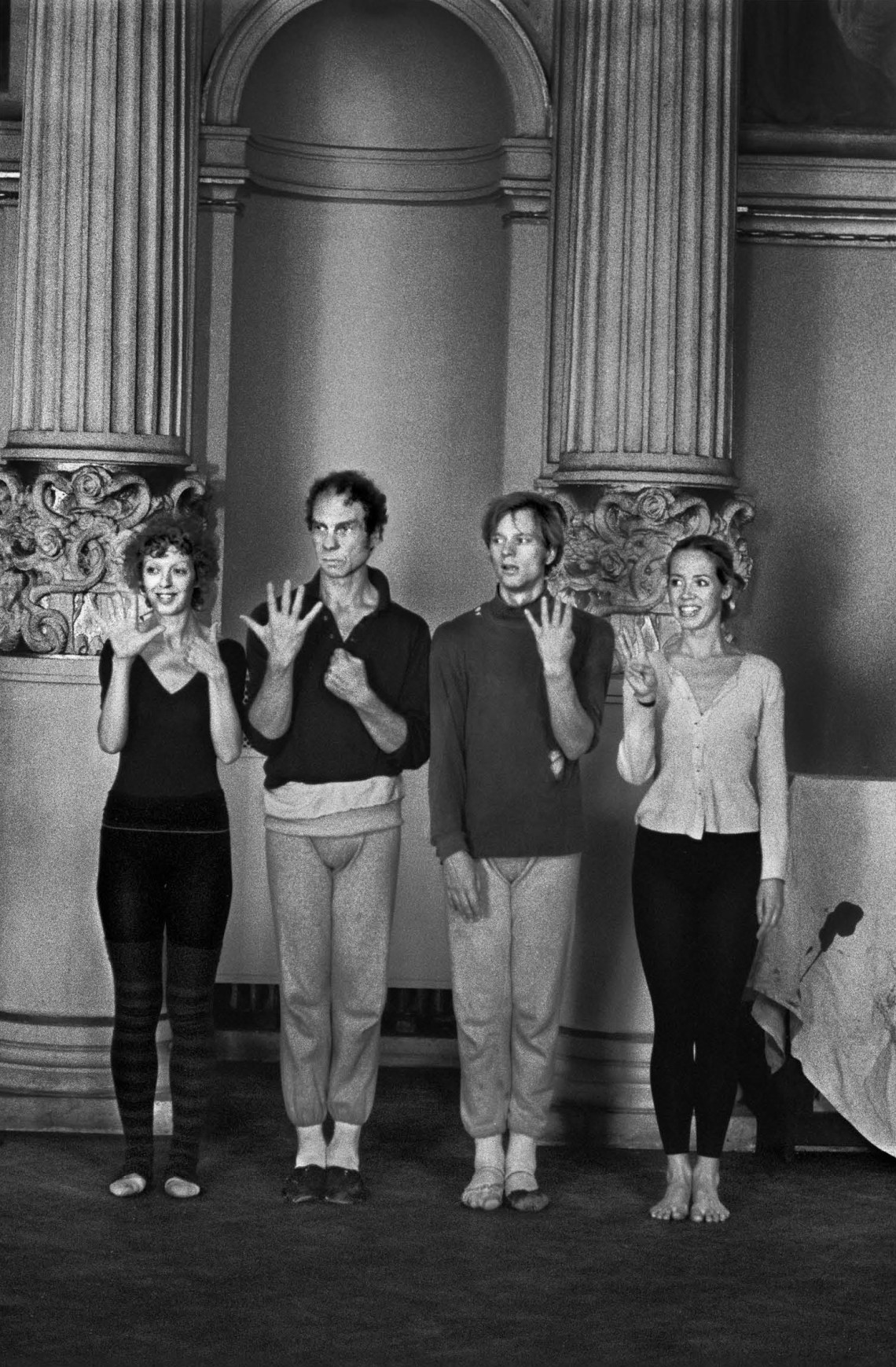

Klosty started spending time with the company when he was dating one of its dancers, Sandra Neels. After they broke up, Klosty began a long relationship with Carolyn Brown, a founding member of the company in 1953 and a principle dancer who performed in about forty pieces over her twenty years with MCDC. In this way, Klosty got to know not just Cunningham and the dancers, but also many of the visual artists—such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns—and composers—such as John Cage, David Tudor, David Behrman, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Gordon Mumma, Pauline Oliveros, Christian Wolff, and La Monte Young—who worked with Cunningham. They are all visually represented in this book—often through pictures of dances on which they collaborated.

Along with the over twenty texts included in Merce Cunningham: Redux, Klosty has contributed a new foreword for this expanded edition. Together, these essays, reviews, interviews, and more offer a deeper sense of both Cunningham and his community of collaborators. One-time MCDC dancers such as Brown, Viola Farber Slayton, Douglas Dunn, and Paul Taylor, write anecdotally, poetically, and personally about Cunningham the dancer, the choreographer, and the man. Particularly amusing is Cage’s account of touring, chance encounters, and meals in his “—Where Are We Eating? And What Are We Eating?” “We descended like a plague of locusts,” he wrote, “on the Brownsville Eat-All-You-Want / Restaurant ($1.50). Just for dessert/ Steve Paxton had five pieces of pie. Merce / asked cashier: How do you manage to keep / this place going? ‘Most people,’ she / replied rather sadly, ‘don’t eat as much / as you people.’” Elsewhere, Oliveros recounts the evolution of her composition “In Memoriam: Nikola Tesla, Cosmic Engineer” for Cunningham’s Canfield (1969) by invoking Cunningham’s liberating mandate that “the music goes its way and the dance goes its way.”

Two reviews of Cunningham’s earliest solo performances in the mid-1940s, by the poet and dance writer Edwin Denby, are prescient in their analysis. “He is a virtuoso, relaxed, lyrical, elastic like a playing animal,” Denby writes. “There is no reason why he shouldn’t develop into a great dancer.” Meanwhile, almost thirty years later, the ballet impresario and visionary Lincoln Kirstein acknowledged his personal fondness for Cunningham and Cage, nevertheless writing that they would be “self-restricted to an audience which is both blind and deaf to the orthodoxy and apostolic succession of four centuries”—in other words, their innovation shattered traditions, but held little hope for a larger public. Betraying his own personal opinion of the work, Kirstein concluded: “I wish John and Merce well, but I am I, and they are they, and never the twain shall meet.”

Advertisement

The years that Klosty photographed, between 1967 and 1972, comprised some of Cunningham’s most mesmerizing collaborations—both new, and those in the repertory at the time. Several of Cunningham’s earlier dances with sets, lighting, and costumes by Robert Rauschenberg (Rauschenberg designed these for the company between 1954 and 1964), were still being performed or were reprised as part of a given tour’s or season’s program during the period Klosty was photographing. These include the playful Antic Meet (1958), which reminds us of Cunningham’s early interest in vaudeville, and the more ominous Winterbranch (1964), which considered, in part, the act of falling, and is set in heavy darkness broken by moments of piercing light.

Equally moody are Klosty’s depictions of Cunningham’s otherworldly RainForest (1968), with Andy Warhol’s helium-filled silver pillows—clouds floating at different heights. The lighting bounces off the clouds, radiant in the otherwise dusky performance area. The dancers wear costumes made by Jasper Johns, the company’s artistic advisor from 1967 until 1980: skin-tight, fleshy leotards and tights, ripped and cut irregularly, which heighten the primeval sensation. Klosty’s pictures of Canfield, with a set by Robert Morris and costumes again by Johns, also utilize the light-play of the set and costumes. Morris’s giant vertical beam traverses back and forth across the front of the stage, shining on the backcloth and the dancers in its path. The backdrop and costumes were “coated with a highly reflective substance, made of minute glass beads, which is often used on traffic signs on highways,” Johns told Klosty in an interview. “At night these signs appear to light up as one approaches them in a car.” In Canfield, the idea was that the dancers and backdrop would be similarly illuminated when touched by the beam’s rays.

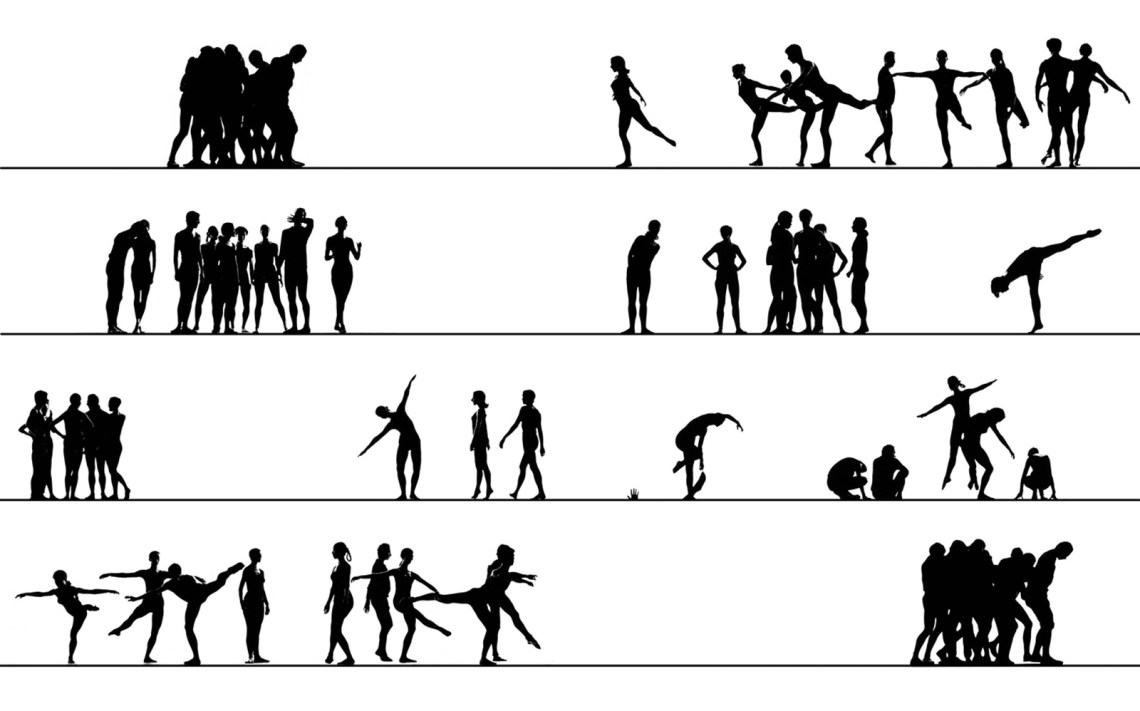

The set for Walkaround Time (1968) was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass. Created with Duchamp’s agreement, Johns fabricated seven mobile, transparent boxes of varying shapes and sizes, painting and silk-screening the images drawn from the original work onto the plastic. A series of black and white images, as well as a gatefold of color images (the only color photographs in the book), blur movement, suggesting how the audience might have perceived the choreography as seen through one or more of the boxes and underscoring the layering effect of dancers and set in motion. Elsewhere, huge industrial fans conceived by Bruce Nauman as the set for Tread (1970), placed in a row, some of them rotating, take on an extraterrestrial feel in Klosty’s images, as the dancers interact with the towering presences. One is reminded of the configurations in a game of Twister in this often comical dance, where the dancers are suddenly all intertwined, or clumped together, before they scatter.

One of Klosty’s biggest challenges must have been how to convey Cunningham’s sensibility and working process. For Cunningham, the choreography, the music, and the set related interdependently—just as movement, sound, and objects coexist in daily life. They are not linked rhythmically—the performers are not dancing to the beat of the music—nor are they working within any kind of traditional narrative. Cunningham generally gave his collaborators some sense of what he was envisioning in terms of duration, as well as kinetically—the experience of making one’s way through a dense forest, for example, or the notion of falling. With these springboards of sorts, the composers and visual artists, unencumbered by the conventions of plotline or character, proceeded independently. This does not mean that the dancers were improvising, any more than Cunningham’s and Cage’s use of chance in their respective processes meant that decisions were not being made. It simply allowed for unanticipated, previously unconsidered possibilities to occur, and it invited a different kind of engagement, even trust, from the audience—as do Klosty’s photographs. Perhaps counterintuitively, his images open up the dances for us, rather than anchoring them, or being reductively illustrative. They don’t tell us how to see or what to think about the dance. They offer us gestures, ambience, interactions—between dancers, between dancers and the set—from which the viewer may make endless associations and interpretations.

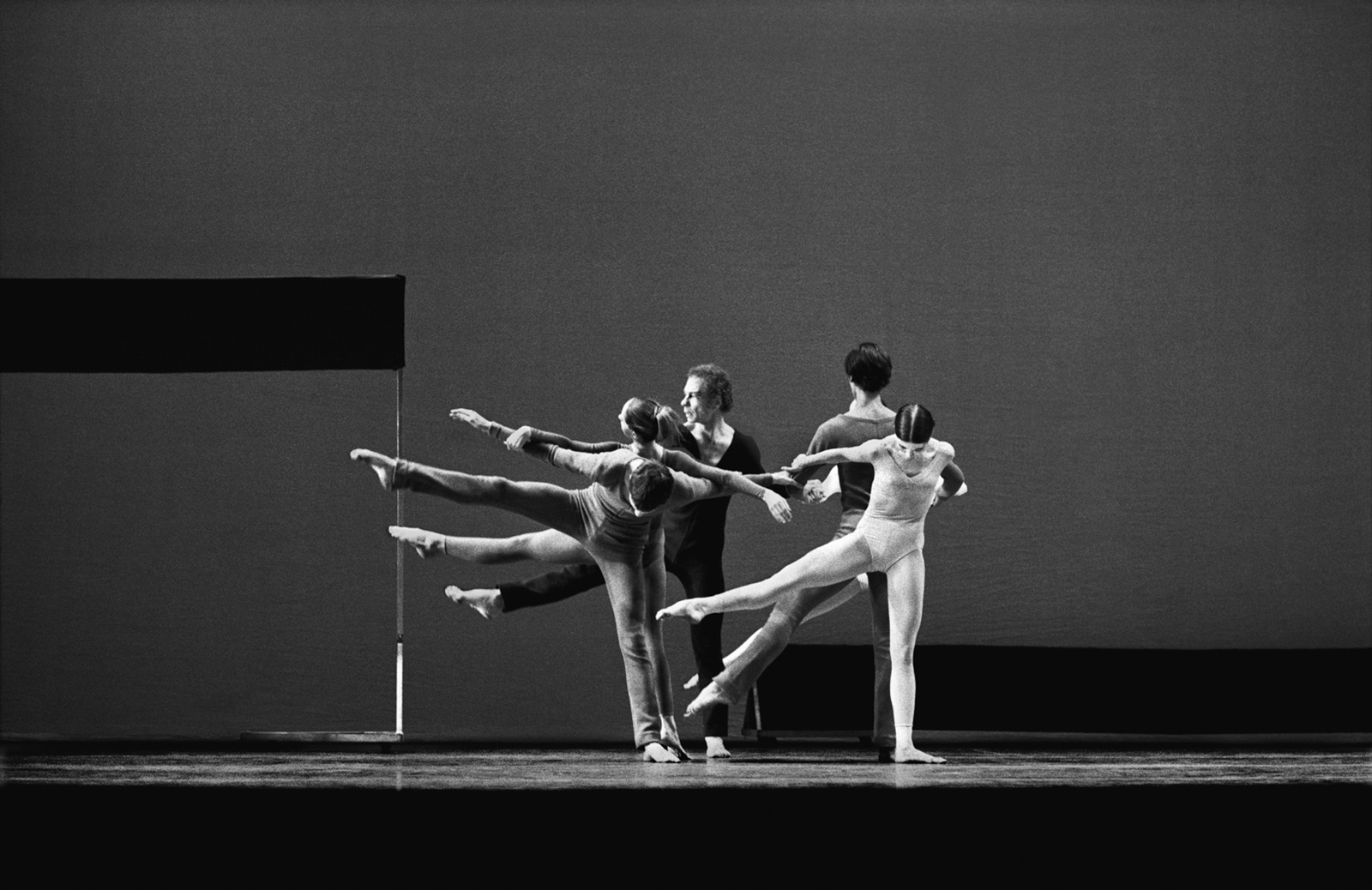

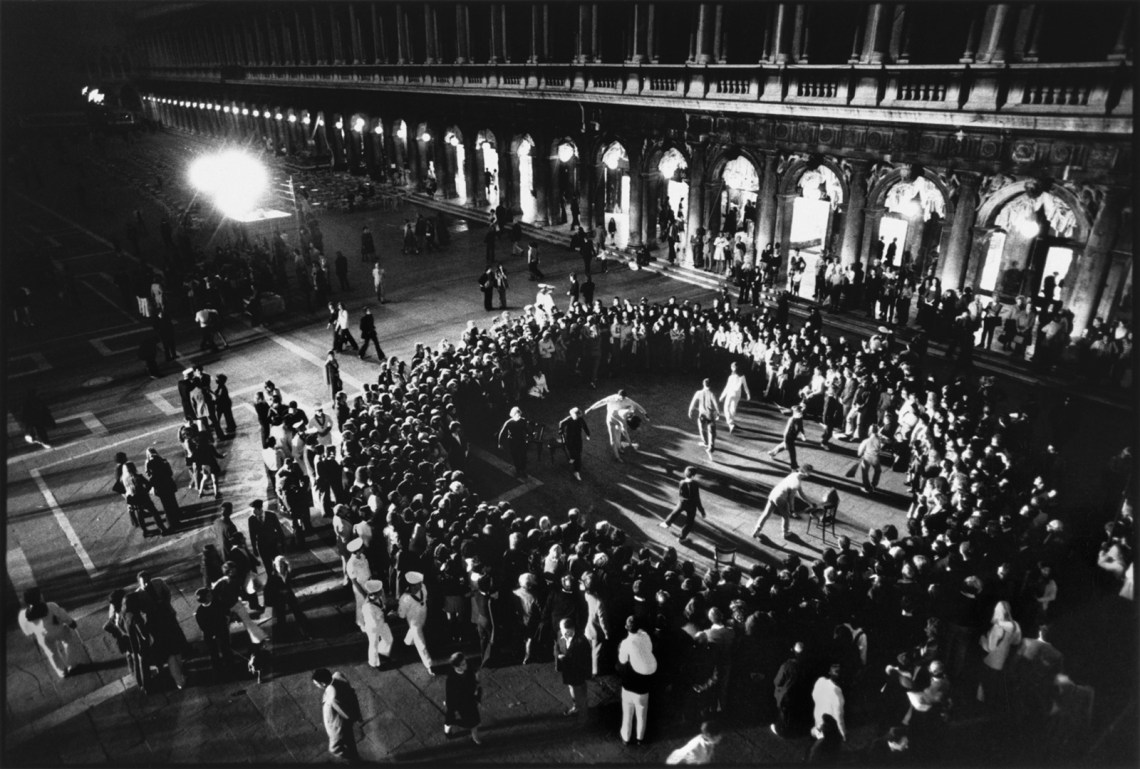

The images of these performances sing with the complexity, precision, and discipline of Cunningham’s vision, and the riveting energy of his presence. When Klosty pulls back, the choreography’s multiple focal points and the nonlinear way the dancers are dispersed onstage is further revealed. Klosty also shows us the often site-specific “Events” that Cunningham orchestrated, culling sequences of movement from various dances and combining them, sometimes with new choreography, to be performed in nontraditional spaces for dance: in Venice’s Piazza San Marco, the dancers seem to variously be moving independently, or partnering—with a person, a broom, or in Cunningham’s case, with a chair (as he did years later in an Event in New York’s Grand Central Station)—as observed from Klosty’s bird’s-eye view; in another, Neels is being dragged across the gallery floor by Chris Komar during a rehearsal for an “Event” in the Belgrade Museum.

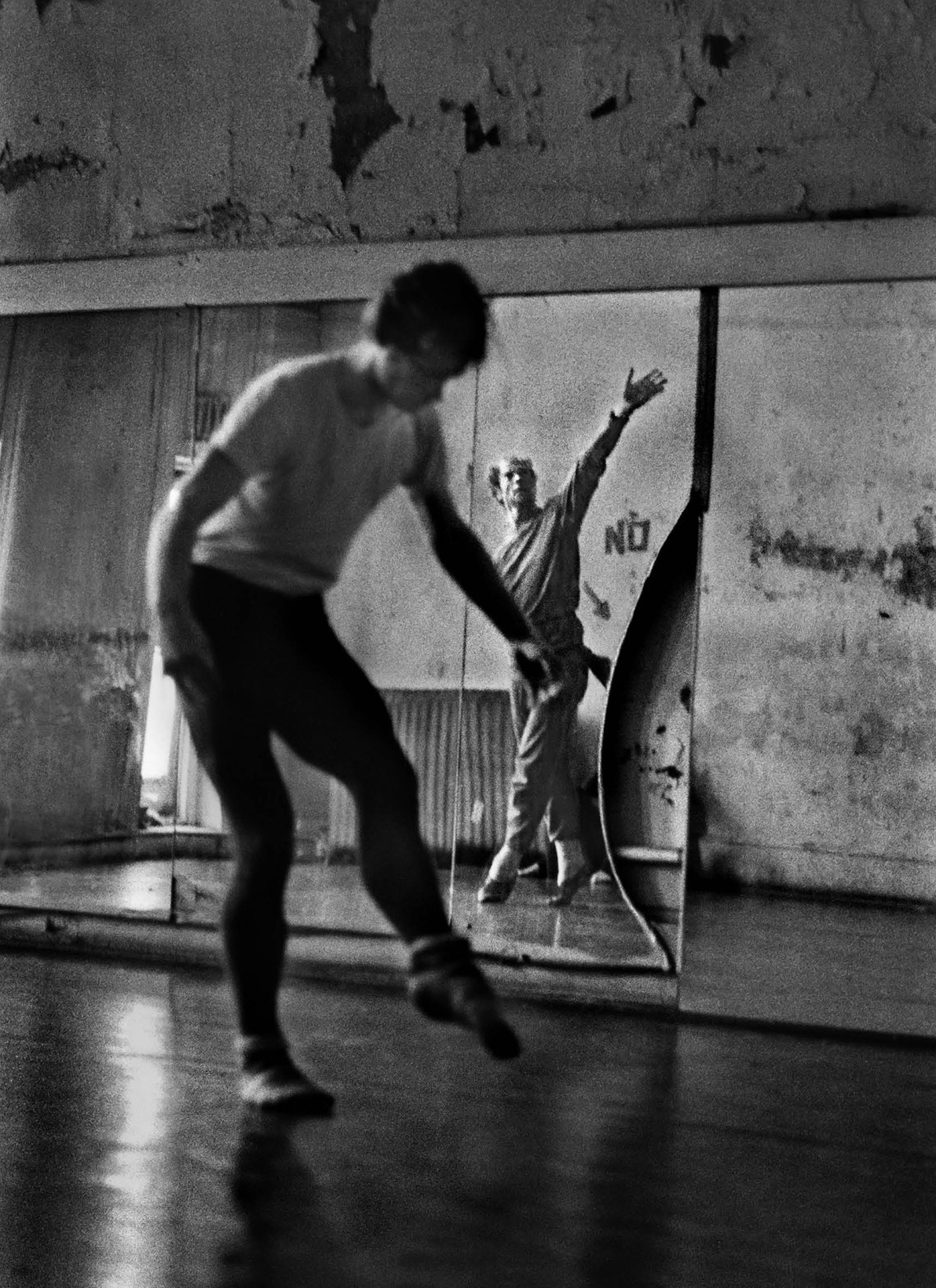

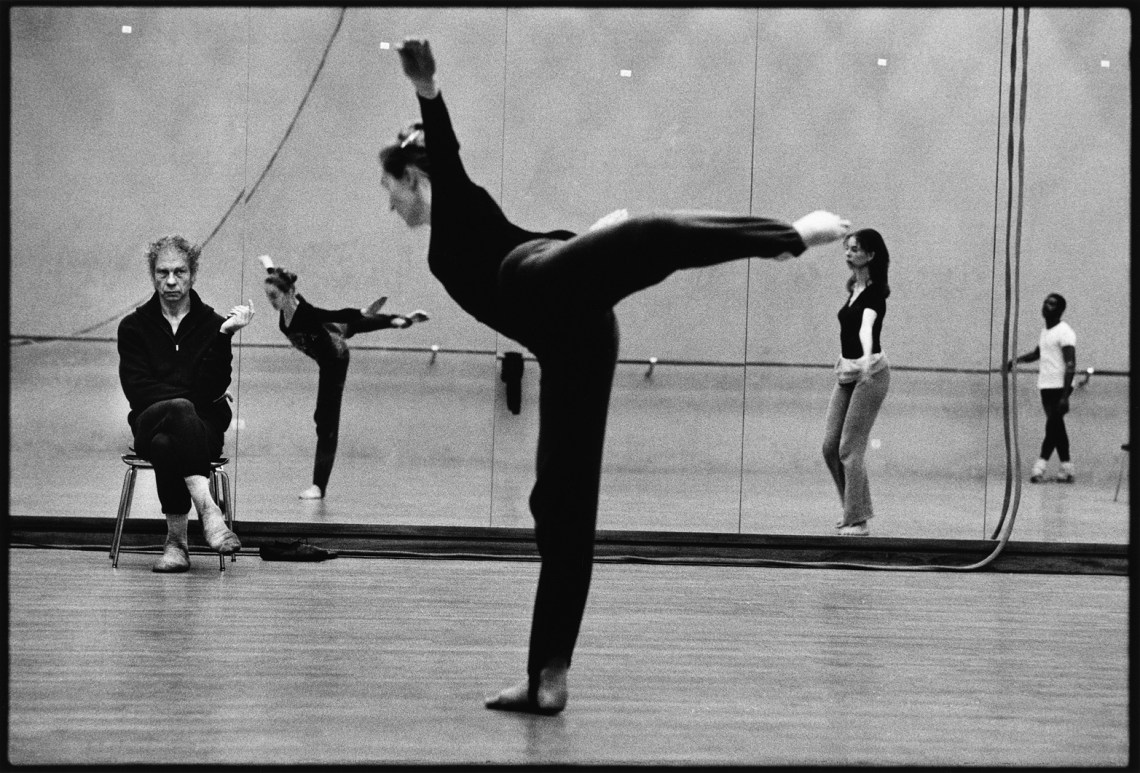

John Cage and Merce Cunningham first met in the 1930s at Seattle’s Cornish School, but it was in 1942, when they saw each other again in Chicago while Cunningham was there performing with the Martha Graham Company, that their lifelong romantic and creative partnership ignited, continuing until Cage’s death in 1992. Cage became the company’s musical adviser from its inception in 1953, but even before that, in April 1944, he and Cunningham put on a joint concert in New York. Klosty’s images of Cage in Merce Cunningham: Redux evoke his intensity, humor, and gentle spirit. (In 2014, Klosty published a large collection of his photographs of Cage made during these same years in John Cage Was.) In one picture, Cage sits at the piano in the company’s Westbeth studio in 1972, looking up somewhat dubiously at Cunningham, who is by his side. Another shows him crouched on the ground in France, also in 1972, bearded with a furrowed brow, cigarette jutting from the side of his mouth, as he harvests mushrooms (Cage was a dedicated amateur mycologist). These kind of candid moments feel especially poignant and telling, as do Klosty’s rehearsal images. Making ingenious use of the studio mirrors, some of the latter convey Cunningham’s laser-like focus, and the intricacies of a gesture or movement being worked through—a spread of six photos show Cunningham rehearsing Neels, Ulysses Dove, Brown, Dunn, Valda Setterfield, and Susana Hayman-Chaffey for the dance Landrover (1972). In another, Cunningham’s exacting and critical eye is trained on Mel Wong and Hayman-Chaffey as they rehearse Signals (1970).

Moving backstage, for example at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, it’s fun to see a seated Johns, who is often described as reticent, smiling as dancer Viola Farber (Slayton), scissors in hand, stands behind him preparing to cut his hair. Elsewhere we see a drying leotard hanging from one of his Target paintings. Other images make clear how unglamorous and exhausting being on tour could be. In one photograph, taken in Holland, the company’s filmmaker-in-residence, Charles Atlas, lies down on the pavement with Mumma, and Mimi Johnson (who would found Performing Art services in 1972—a not-for-profit dedicated to helping contemporary performing artists with all aspects of getting their work produced and presented), perhaps napping, as dancer Carolyn Brown sits against an adjacent brick wall, head tilted back, legs apart, staring into nowhere.

Opposite the opening page of Klosty’s introduction is an image captioned “The photographer and his subject,” in which Cunningham, dressed in dark colors, sits on a chair in front of a wall of mirrors, head facing sideways with one hand covering his nose, eyes, and forehead, the other hand holding the back of his head, his feet crossed. Reflected in the mirror is Klosty, squatting on the floor across the room, dressed in white, holding the camera to his face. Klosty once told me that the image “so perfectly encapsulates” his early experience of photographing Cunningham.

Why did Cunningham permit Klosty the access he did? Perhaps he understood the photographer’s commitment to presenting the company in a nuanced and rigorous way. Perhaps it was because the dancers seemed comfortable in his presence. Or maybe it was a matter of habituation—how a photojournalist, or scientist, studying animals in the wild may, with sensitivity and patience, be accepted, or at least tolerated, over time. Nothing escaped Cunningham’s keen and obsessive observation. Had he not wanted Klosty there—no matter how unobtrusive he was—that would have been that. Or maybe Cage, who was always looking out for Cunningham, as well as considering what might benefit the work in some way, liked and appreciated Klosty and his talent, and encouraged Cunningham to be open to the idea.

Klosty had a profound knowledge of the work and all those in MCDC’s orbit, and had clearly earned Cunningham’s respect. I imagine that Cunningham came to understand not only the value of this kind of in-depth documentation, but the independent strength of the photographs as well. The elemental vitality and spirit of these images will forever celebrate Merce Cunningham’s groundbreaking work, to which he devoted his heart, mind, and body. “You have to love dancing to stick to it,” he said. “It gives you nothing back… nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.”

Merce Cunningham Redux by James Klosty is published by powerHouse Books.