At the National Gallery, Room 1 is tucked away at the front of the building, on the first floor landing. As you turn toward it, you look down at the stream of people climbing the marble staircase, tourists holding floor plans, parties of students and schoolchildren with clipboards. Room 1 is like an eddy beside a flowing river. The small exhibitions shown here may highlight a single work from the gallery, or direct us to an underrated artist, or explore connections with the later visions of another artist—as one did in 2018, linking the stark, industrial landscapes of Ed Ruscha’s Course of Empire (2005) with Thomas Cole’s cycle of the 1830s, on show elsewhere in the gallery.

That kind of connection is the rationale of the current show, “Young Bomberg and the Old Masters.” But it’s a shock, in the gloom of Room 1, to confront the sharp angles and singing colors of David Bomberg’s canvases of the 1910s, and the great figures found in Sappers at Work, of 1918–1919. What are they doing here? They belong in the Tate, and this exhibition is a good collaboration between sister galleries, but still, their presence in Room 1 jolts our expectations. It’s at once exciting and sad: all these early works, in different ways, have undertones of pain and passion, and it’s poignant to think that Bomberg never knew they would be on show here, in the National Gallery he loved.

Bomberg’s life was hard—as Fran Bigman noted in these pages, reviewing the Bomberg show at the Ben Uri Gallery for the NYR Daily in 2018. The fifth of eleven children of a leather-craftsman, growing up in crowded rooms in Whitechapel, in London’s East End, he fought to become an artist, opposed by his father but encouraged by his mother. From the start, he looked to classical works for inspiration, but he had no hope of formal art education until, by chance, in 1907 John Singer Sargent noticed him in the Victoria & Albert Museum, drawing the cast of Michelangelo’s The Rebellious Slave. With Sargent’s help and support from the Jewish Educational Aid Society (later withdrawn in disapproval of his work he went to the Slade, where fellow pupils included Mark Gertler, Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, and Isaac Rosenberg (with whom he walked every day from the East End to save the Undergroundfare).

Shocking his tutors, Bomberg was a blazing radical, influenced by Italian Futurists and by the Cubist experiments of artists he met in Paris on a trip with Jacob Epstein in 1913, including Picasso and Modigliani. Declining Wyndham Lewis’s invitation to join the Vorticist movement, Bomberg set off on his own. The following year, aged twenty-three, in the catalogue of his first solo exhibition at the Chenil Gallery, Chelsea, he wrote with urgent emphases, “I APPEAL to a Sense of Form.” In his work, he explained, “I completely abandon Naturalism and Tradition. I am searching for an Intenser expression… I hate… the Fat Man of the Renaissance.”

Yet he loved that Fat Man, too. Taking his sister Kitty to the National Gallery to see a favorite painting, Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man (circa 1480–1485), he told her how he wanted to draw himself based on this painting, and asked his father “to design a shirt like the Botticelli garment.” Wearing this shirt in his Self-Portrait (1913–1914), his head tilted slightly down but sharing the direct expression of Botticelli’s youth, Bomberg faces us, assured and confident.

Richard Cork, the show’s curator, finds echoes of numerous National Gallery paintings in Bomberg’s work, ranging from Poussin’s Bacchanalian Revel (1632–1633) to Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533). In his eloquent catalogue essay, Cork offers masterly close readings of Bomberg’s paintings, but his conclusions about what the painter drew from particular Old Masters are purely speculative, and while I admire the immersive attempt to see through Bomberg’s eyes, I’m not always persuaded.

Perhaps this is because only two older works—the Botticelli portrait and The Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, from the Studio of El Greco (1590s)—are actually shown in the Room 1 display. (We have to hunt elsewhere in the gallery for the rest.) But it’s more that the intense connections with the artist’s own life and community drown out the visual ghosts. Looking at Visions of Ezekiel (1912), for example, a painting based on the story of the Prophet Ezekiel magically resuscitating a valley of scattered bones with his utterance “O ye dry bones, hear the word of the Lord,” it is easier to link the death of Bomberg’s mother to this dream of joyful resurrection than it is to trace a reference to Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523). Yet Cork does make one think, so that when he connects a pose to the angels’ embrace in Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity (1500), I began to see a similarity of gesture as well as a model of solace.

Advertisement

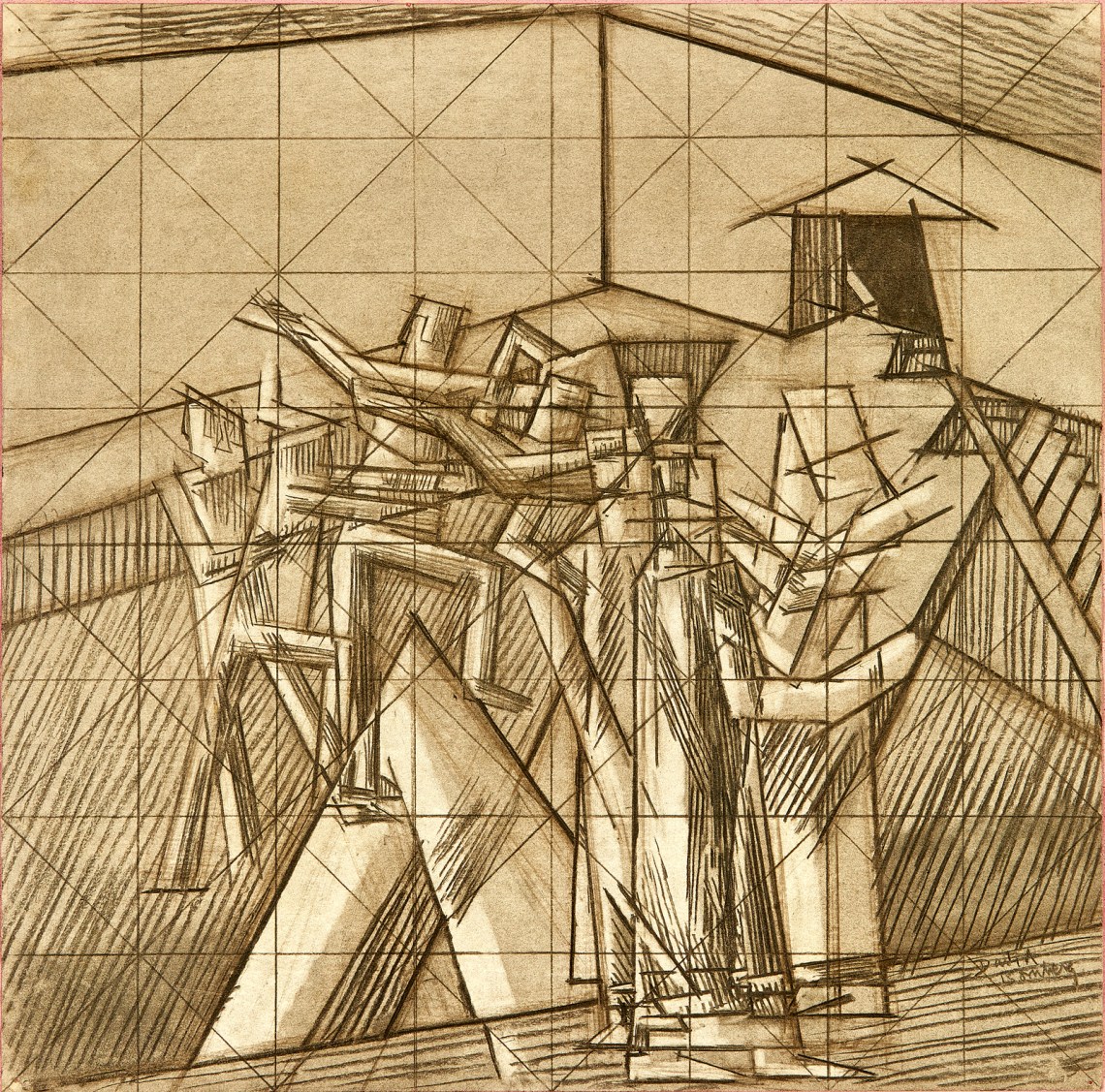

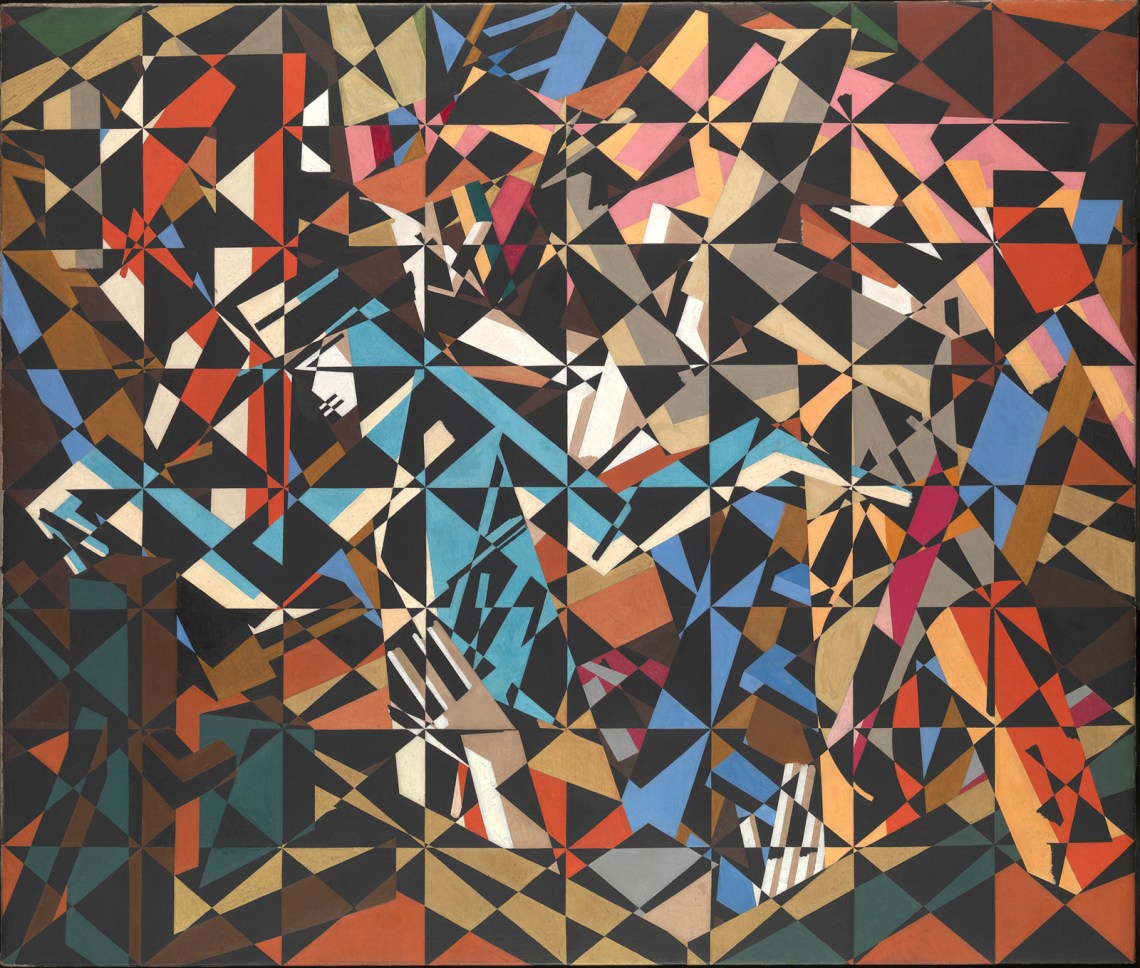

Bomberg took his formal journey further in Ju-Jitsu (circa 1913), spurred by his watching Japanese wrestling in the gym where his brother Mo trained as a boxer. In the charcoal study, one can indeed recognize the raised knees that Bomberg would have seen in Botticelli’s Venus and Mars (circa 1485) and Bassano’s Good Samaritan (circa 1562–1563). Any legible limbs vanish, however, in the grid imposed on the final painting to break up the form.

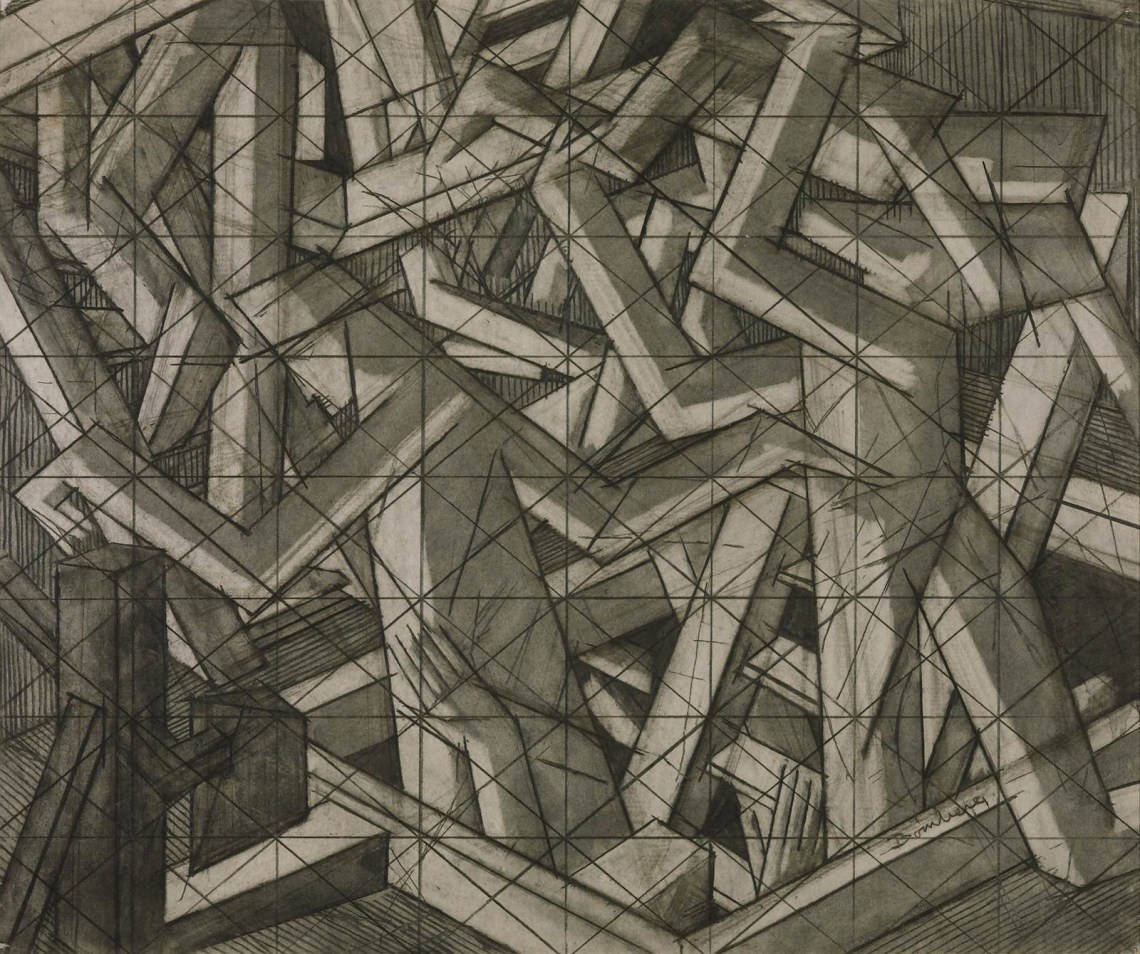

The charcoal study for the next painting, In the Hold (1913–1914), is very moving, with a hatted figure clambering out of the hold, a man holding a child above his head, a ladder descending into the depths, while in the finished canvas the grid’s effect is even more complex and disorienting. The figures are split into a tumult of geometric forms, much as the immigrants coming off the ships must have felt their lives spinning out of control. The grid was a way of holding emotion at arm’s length: art, Bomberg declared, “has too long suffered from what I may call a literary romanticism from which I desire to emancipate it.” Yet it is the transmission of feeling, as much as gesture, that he gleaned from the works Cork cites here: Leonardo’s The Virgin of the Rocks (circa 1491–1492 to 1506–1508), Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaeus (1601) and Veronese’s Unfaithfulness (circa 1575).

His most controversial work of these years was The Mud Bath (1914), an allegory of purification prompted by the popular Schevzik’s Vapour Baths in Whitechapel’s Brick Lane. At Bomberg’s insistence, this painting was hung outside the Chenil Gallery like a flag—or a red rag to the critics. The grid has gone here, and the blue and white forms plunging into and climbing out of their red rectangle have a dazzling zing and movement. We should think, Cork says, of the smiling Hendrickje Stoffels with her shift up above her knees, modeling for Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing in a Stream (1654); of the hieratic forms of Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ (after 1437); and the leaning, straining figures of Michelangelo’s Entombment (circa 1500–1501). (Bomberg took his first wife, Alice, to view the Entombment, telling her only that they were going “to see a real picture,” making her shut her eyes until they reached it.)

In September 1914, the recent outbreak of World War I closed the Chelsea show, after only a month—making the exuberant Mud Bath seem, in retrospect, a prophecy of the mud and death to come. Bomberg himself fought and suffered greatly in the trenches. Then, in 1917, he was commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Fund (started by the newly ennobled Lord Beaverbook, later a great newspaper magnate) to paint Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company. The scene chosen was of a 1916 operation of the Royal Engineers that involved mining beneath German lines at St. Eloi in France, and in this huge canvas, the last in the show, Bomberg turned his back on abstraction. His figures rise gnarled, strained and majestic—you feel their fleshiness—and his paint is applied in thick, sensuous strokes, the colors shining against the blue planks. Here, one can indeed trace debts to works like Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s Battle of the Nudes (circa 1467–1495), and to figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1535–1541), but the painting is imbued with reverence for the heroes of more recent history, a passionate admiration for the sappers themselves.

Once again, Bomberg was rebuffed. His painting was refused on the grounds of its contorted figures and bizarre colors, and he was forced to paint a second, still impressive but more conventional rendering. In his original Sappers at Work, he was already moving toward a new style, and now he turned from the machine age and the darkness of war to nature and landscape, hoping to develop, as he said in an interview late in life, in 1953, by finding again “that the world was round and there was a way out through the sunlight.” In 1915, he and Alice went through all his early material, discarding his experimental drawings and thrusting them into a fire. Together, she wrote, “we spent days destroying years of careful work.”

Advertisement

Life would never be easy, and although Bomberg became an inspiring teacher, as pupils like Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff have testified, his own greatness went unrecognized in his lifetime. The unsold paintings from the 1914 Chelsea show were resigned to storage, never seeing the light again until the Tate bought them in 1957, after Bomberg’s death. It is wonderful to see them here.

“Young Bomberg and the Old Masters” is at The National Gallery, London, through March 1.