Announcing, in a letter from 1971, that she planned to teach a seminar at Harvard “on ‘Letters’!,” Bishop described the subject matter as “Just letters—as an art form or something.”

Rather than generalize further, she sketches a syllabus, demonstrating her idea for this course by examples: “I’m hoping to select a nicely incongruous assortment of people—Mrs. Carlyle, Chekhov, my Aunt Grace, Keats, a letter found in the street, etc. etc.” The list’s “nicely incongruous” quality points out that the letter is a genre used not only by literary artists like Keats and Chekhov, but by ordinary people like Bishop’s Aunt Grace, and by women who were brilliant writers in the genre but not published in their lifetimes, like Jane Carlyle, as well as by celebrity authors like her husband, the Victorian polymath Thomas Carlyle who declared that “the History of the world is but the Biography of great men.” Bishop’s list also points out that, once detached from the moment and circumstances of its composition, there is something impersonal and strange about any piece of correspondence. On that level, every letter is “a letter found in the street.”

That Bishop is writing about her letters course in a letter points up other aspects of the form. The informality of her prose in letters is essential: its playfulness, apparent spontaneity, and nonchalance (sometimes even sloppiness, as in that double “etc. etc.”) simulate a voice in conversation, with the aid of writerly tools like dashes, italics, and scare quotes, which make her tones and accents audible. The premise of that informality is the intimacy of her address: typically, Bishop’s correspondent is familiar, indeed a friend, or a friend in the making, rather than the anonymous reader of a book or magazine. The relationship is based on trust, even affection; and the casualness of the communication keeps whatever she has to say fluid, unpretentious, keyed to the particular occasion, and embedded in the performance of a personal style for a select audience.

In this case, she is writing to Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale—duo pianists, authors, and domestic partners with whom she had exchanged gossipy letters since Lota de Macedo Soares, her partner in Brazil, introduced her to them in the early 1950s. Because manners and style are paramount in letters, and much goes without saying in them, letters were an important vehicle for gay sociability in an era when there were strong constraints on speech about sex and sexual identity. Writing to Gold and Fizdale, Bishop does not have to hide or declare the nature of her relationship with Lota; she can simply hand the pen to her, as when she and Lota take turns writing a letter to Gold and Fizdale in 1952, a letter-writing practice something like playing four-hand piano, as Gold and Fizdale no doubt appreciated.

Letters are collaborative. They introduce chains of interaction, soliciting response, as Bishop does when she breaks off her list of letter-writers and asks Gold and Fizdale to help her plan: “But I need some ideas from you both—just on the subject of letters, the dying ‘form of communication.’” There is here, as in many Bishop letters, a mood of mild, amused conspiracy. She is pleased to smuggle into the Harvard curriculum a subject as personal, pleasurable, and therefore trivial-seeming as correspondence; and she is pleased to share the plan with these friends. If letters are “the dying ‘form of communication,’” Bishop and her friends can smirk at the style-less sociological idiom in which this idea is expressed, knowing that, in their case, letter-writing is alive and well.

*

Just how important letters were to Bishop, and what a central place they have in the body of her work, has become clear in stages after her death, as her correspondence has been mined for works of criticism and biography, and edited for publication in books and journals. David Kalstone’s Becoming a Poet: Elizabeth Bishop with Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell (1987) was the first book to draw heavily on Bishop’s correspondence with Moore and Lowell in order to narrate her evolving sense of poetic vocation. Bishop’s letters were a primary source for Brett C. Millier’s Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It (1993), the first biography of Bishop. One Art, the first and still the most comprehensive selection of her letters, appeared in 1994, reinforcing the biographical approach that had begun to dominate readings of her poetry by that time. Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell (2008) presented both sides of her long dialogue with Lowell. Elizabeth Bishop and ‘The New Yorker’: The Complete Correspondence (2011), collected her back-and-forth with Katherine White and Howard Moss, who published the majority of her poems over four decades in their roles as editors at The New Yorker. Editions of Bishop’s correspondences with Marianne Moore and with May Swenson are in preparation. Moreover, a great many Bishop letters have not been published, and new letters continue to come to light.

Advertisement

Bishop’s New Yorker correspondence shows her making friends with her editors, discovering shared points of reference, personalizing their professional dealings, and ultimately creating deep friendships. Something similar happens in the 1960s in her correspondence with Anne Stevenson, who had written to Bishop to gather information for the first critical book about her work (both sides of that correspondence were included in Bishop’s collected Prose in 2011). Bishop’s address to her evolves over twelve months from “Dear Mrs. Stevenson” to “Dear Mrs. Elvin” (her married name) and “Dear Anne” to “Dearest Anne.” Bishop comes to trust Stevenson as they exchange personal information and establish a common idiom, a way of talking easily with each other. In the process, Bishop’s letters get longer and longer, more confiding and at ease, until this famously reticent author has used their correspondence to give a detailed account of her family history, described the development of her poetic career, and meditated on her preferences in music, art, and literature, along with much else.

A passage from the longest of her letters to Stevenson, from 1964, known as “The ‘Darwin’ Letter,” was one of the first pieces of her correspondence to gain attention when it was excerpted in Elizabeth Bishop and Her Art (1983). The passage begins: “There is no ‘split.’ Dreams, works of art (some), glimpses of the always-more-successful surrealism of everyday life, unexpected moments of empathy (is it?), catch a peripheral vision of whatever it is one can never really see full-face but that seems enormously important.” Bishop goes on to talk about her admiration for Darwin, whom she pictures as a “lonely young man, his eyes fixed on facts and minute details, sinking or sliding giddily off into the unknown.” That image directly leads to a summary statement about the nature of art. For Bishop, artist and audience have a parallel and equivalent experience of it: “What one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is the same thing that is necessary for its creation, a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.” The whole passage can be pored over. Rich in imagery that links up to Bishop’s poetry, and rhythmically complex, it is like a poem itself.

But in its excerpted form, which critics have often quoted, the fact that it is part of a letter, written in response to Stevenson’s comments on Bishop’s work, gets lost. Shorn from the excerpt was the beginning of it—“Yes, I agree with you”—and the question Bishop posed at the end of it: “(In this sense it [the experience of art] is always ‘escape,’ don’t you think?).” That question complicates her otherwise final-sounding statement, leaving the idea open-ended, in need of further discussion. Once we restore it to its context, we recognize the passage’s dense, probing, speculative prose as dialogic and specifically epistolary. Bishop’s careful second-guessing and self-questioning are ways of engaging and acknowledging her correspondent. This is not trivial politeness on her part, but an effort to get at an idea by sharing it, even while, or precisely because, the letter’s conversational form keeps Bishop’s thinking unsettled, mobile, incomplete. Her letter gives a “peripheral” rather than “full-face” view of her “enormously important” subject.

There is a purposefully sketchy, offhand quality to Bishop’s thinking in letters, as in her definition of the letter itself as “an art form or something.” We might see the style as imprecise, and find it curious in a poet particularly noted for her precision of observation. But imprecision of this sort in her letters appealed to Bishop because it prevented her ideas from becoming prematurely or permanently fixed, as they would be in print. Letters allowed her to speculate, muse, joke, hesitate, qualify, and change her mind, all in the course of a letter, or sometimes in the course of a sentence. In letters, Bishop could try out sharp, avowedly partial opinions, rather than patiently build up arguments and take reasoned positions for which she would be held publicly accountable, as demanded by the book reviews she struggled to complete. Letters allowed her to mix subjects in meandering association, or with less connection than that, shaped only by the flow of thought and the chance nature of experience.

Each of Bishop’s important correspondences has its own character and dynamics. But the series of letters she wrote to her psychoanalyst, Dr. Ruth Foster, over a few days following her thirty-sixth birthday in February 1947, is unique in its intensity. These letters detail Bishop’s sexual history and its connections to her creativity in an extended reverie, probably written at the suggestion of Dr. Foster as part of Bishop’s treatment. Although unpublished, they can be read in Special Collections at the Vassar College Library, which acquired them after the death of Bishop’s literary executor, Alice Methfessel, in 2009. By now they have been discussed in essays and academic papers, and used as evidence by Bishop’s most recent biographers. Bishop wrote them on a typewriter, filling to the margins more than nineteen sheets of paper and another two pages or so of personal chronology. Begun under the influence of three quarts of whiskey—as she confesses, or perhaps boasts, using drink as an excuse and permission for the outpouring to follow—the letters relate dreams, certain visionary experiences, anxieties, anecdotes, childhood memories, desires, pleasures, sexual habits, ideas for poems, and, above all, Bishop’s loving devotion to and personal trust in her psychoanalyst. The pages have been folded in half, not in thirds as they would be if they had been mailed in a standard-sized letter envelope—which suggests that Bishop presented the letters by hand and as a single document to Dr. Foster, and that Dr. Foster returned them the same way, making the communication hand to hand and that much more intimate and personal.

Advertisement

The Foster Letters, as they are known among Bishop scholars, are shocking in view of the poet’s reputation for refinement, calm, and reticence. Gradually, over the decades since her death, the publication of Bishop’s draft poems and poems she completed but did not publish, including in particular the collection edited by Alice Quinn called Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box (2006), have shown Bishop to be a poet of surpringly frank erotic power and complexity. But the Foster Letters include personal revelations of another order. It is tempting to see those revelations as simple facts that can be extracted from their context and plugged into Bishop’s life story. But that would be to ignore the way that they are embedded in Bishop’s tangled, careening address to her analyst. Statements in a letter always demand interpretation and contextualization—all the more when the letter takes the form a quasi-psychoanalytic monologue in which dreams and hallucinations are under discussion, and conscious and unconscious role-playing prevails. When Bishop tells Dr. Foster she was sexually abused as a child by her uncle, is she exaggerating or underplaying the abuse? What is Bishop really saying when she announces to Dr. Foster, “I have no clitoris at all”?

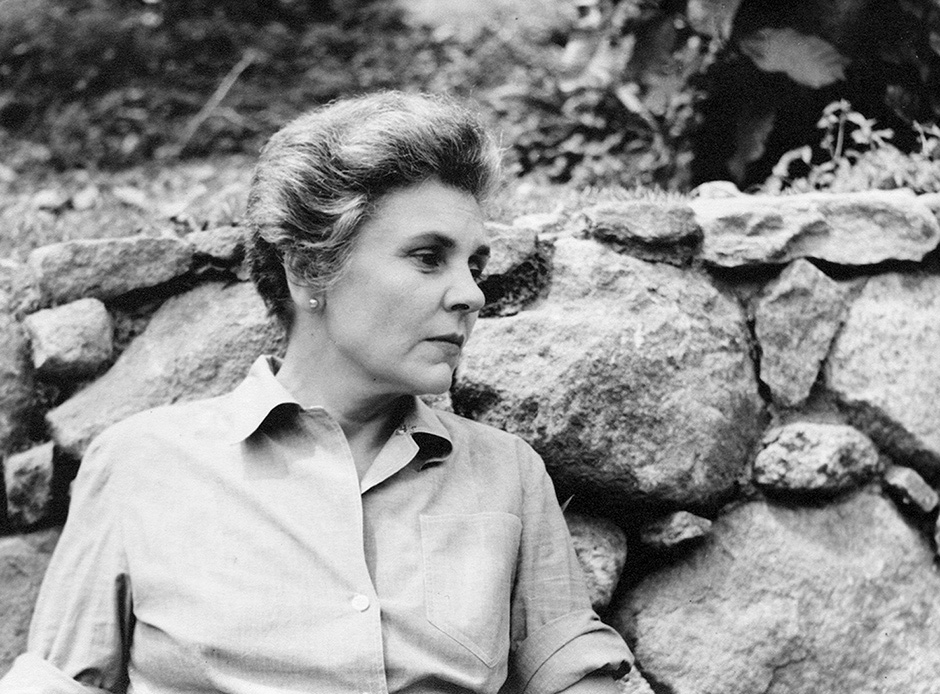

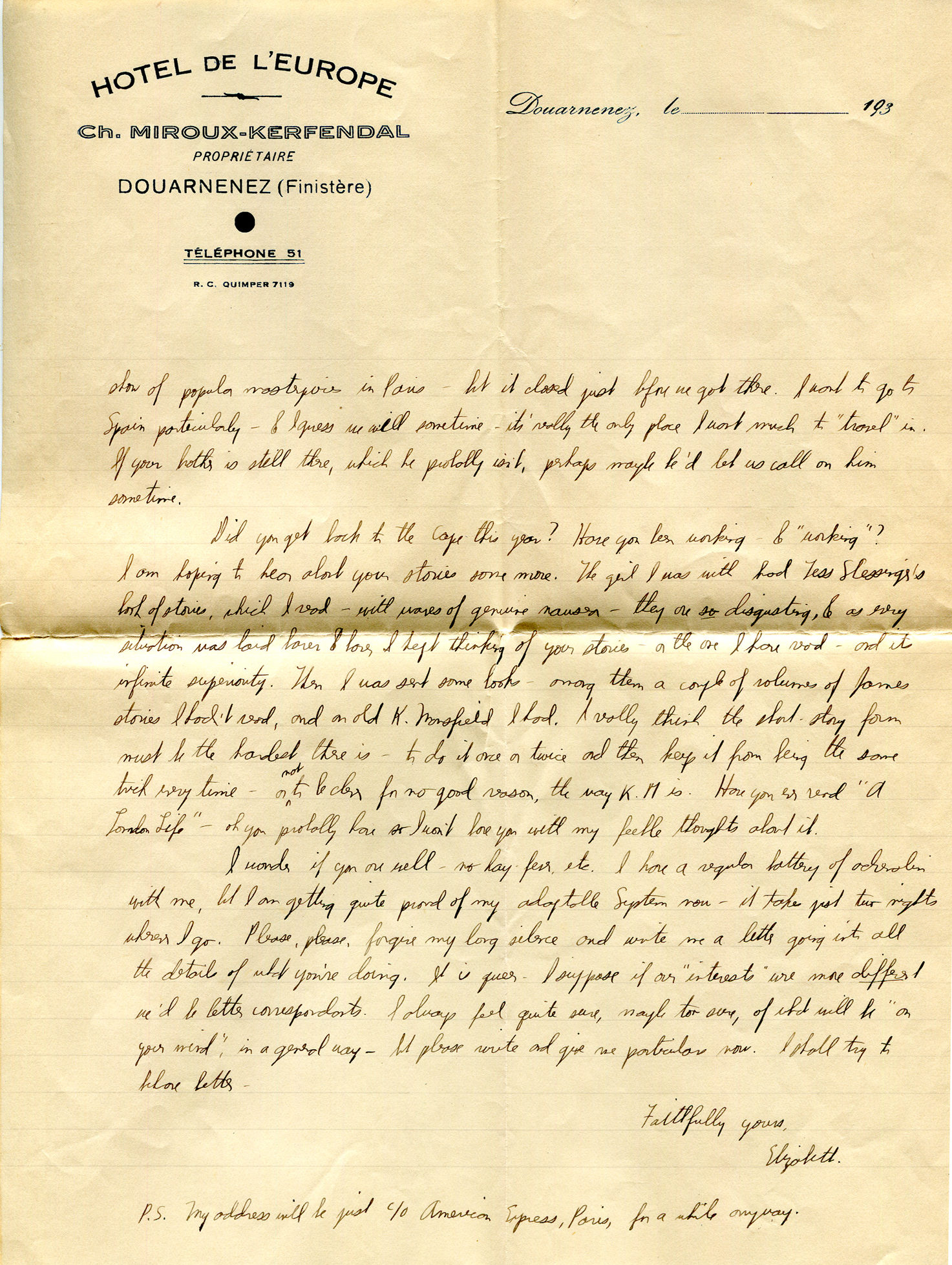

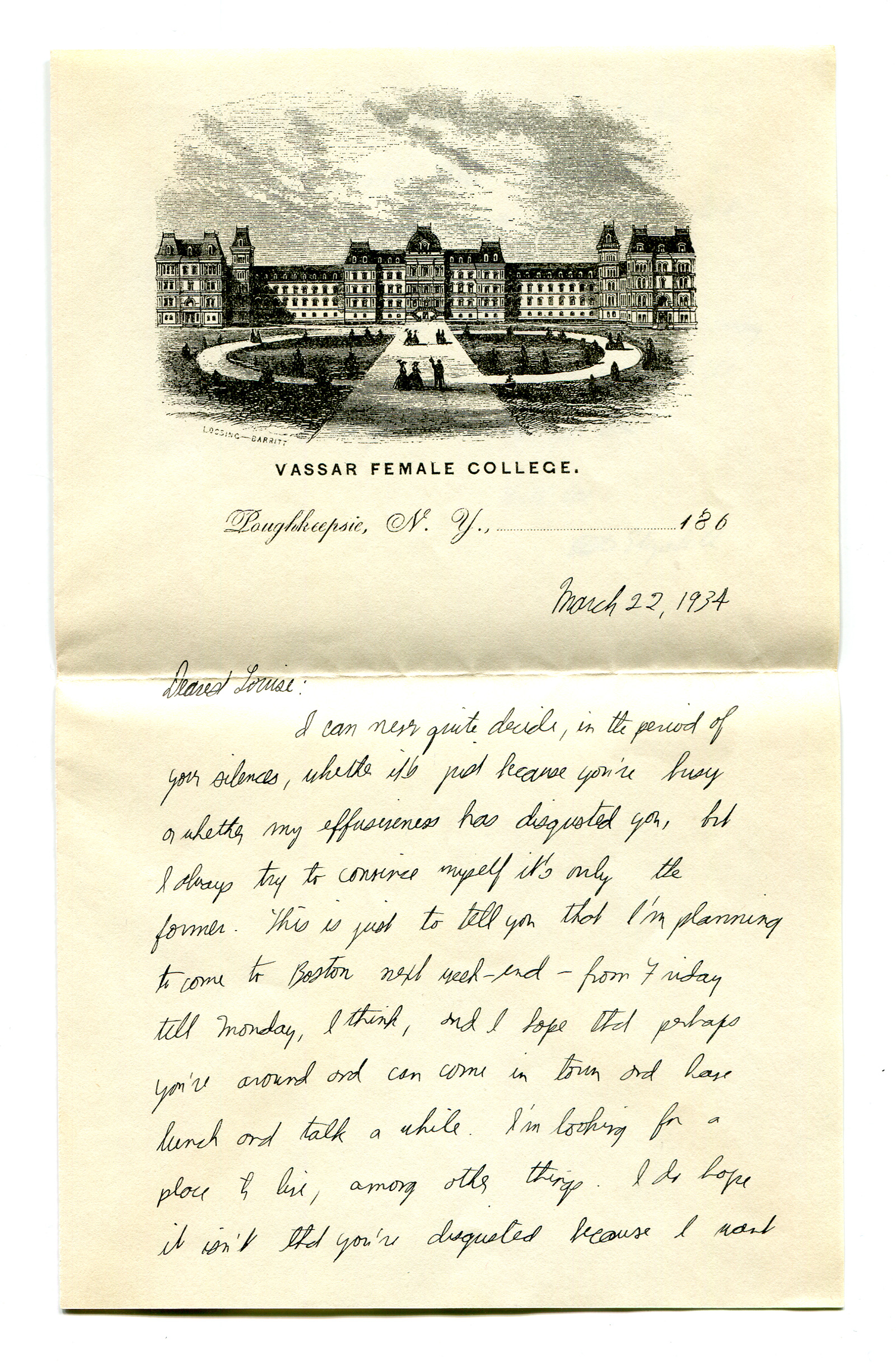

Less sensational but no less revelatory than the Foster Letters are Bishop’s letters to Louise Bradley, another unpublished correspondence. Fourteen-years-old at the time, Bishop met Bradley in 1925 on the train platform in Boston when they were both on their way to camp on Cape Cod. Bradley, three years older and in her last year of camp, found Bishop, a first-time camper, standing among the girls she was greeting. “I don’t know you,” she said to Bishop, “but I’ll kiss you, too,” as Bishop later repeated the introduction back to her in a letter. They became close friends at camp, and, although—or because—they met only infrequently after that, they exchanged letters (over sixty by Bishop) through Bishop’s high school and college years. There are only a few pieces of correspondence dated after 1934, and Bradley’s side of it is almost entirely lost, save for a witty valentine and drafts of a letter she may not have sent.

The gaps in this correspondence and the many questions they raise are typical of the biographical problems posed by letters. How did Bradley think of Bishop? Were her letters to “Bishie,” as Elizabeth signs herself in hers, equally devoted and passionate? To make sense of a correspondence, however complete or incomplete, is to constellate fragmentary evidence, and make surmises about what is missing (including what may not have been apparent to the letter-writers themselves). Even so, a picture of the teenage Bishop emerges here. In her letters to Bradley, she is reveling in the excitement of a same-sex intimacy, gaining the confidence to declare her likes and dislikes, accepting her felt difference from her schoolmates and the adults around her, boldly claiming her ambition to write poetry, and discovering that letters allow her to connect all these developments, and push forward in life.

Bishop’s letters to Bradley sometimes include poems that she has written, or her comments on Bradley’s poems. They are full of intimations of the poet Bishop would become, as well as, crucially, ideas about the style of life she imagined for herself as a poet. These are suggested by a persistent fantasy of travel to an exotic, isolated, usually island locale with her “Dearest Kindred Spirit.” Here are two elaborations of Bishop’s vision, from 1926 and 1927 respectively:

Louise—is it right for a young woman to trail off to the ends of the earth—Norway—India—alone? And live in strange places and do strange things—or two young women. You come with me. When my — — — education is finished. Lets. And then retire to Ireland and raise bees—and live by the ocean in a stone cottage—and write poetry for a living. Oh!! Will you!

I’m going to live in Tahti [sic] or one of those islands with a piano and stacks of books—and the sea and sun—and stars. So you must come with me and bring the Irish harp and we’ll play together—not just music. Wouldn’t you like to live on a South Sea Island—and forget calendars, and church and subways, and doctors, and Logarithms? Say yes or rather, write it to me.

Fifty years later, Bishop published “Crusoe in England,” in which Crusoe remembers his life on the island with Friday. Bishop had by then lived out versions of the idea behind the poem with Louise Crane and then Marjorie Stevens in Key West, Macedo Soares in Brazil, and Alice Methfessel on the island of North Haven in Maine. Her letters to Bradley demonstrate that the idea was coeval with her wish to be a poet and her discovery of romantic feeling for girls, and that it was fully formed as early as her adolescence. The future life that these letters project will include strangeness and domesticity, escape and adventure, solitude and companionship, books and the senses, the sea and the stars. Meanwhile, short of actually setting out for Tahiti, Bishop invites Bradley to join her on the private island constituted by their letters, where love and poetry already flourish. “Say yes,” Bishie begs her friend, “or rather, write it to me.”

*

Bishop stopped regularly writing letters to Bradley after she graduated from Vassar and began to correspond with Marianne Moore. Bishop’s letters to Moore start out as a courtship in which Bishop adopts a deferential tone, produces distinctive gifts calculated to please Moore’s eccentric sensibility (for example, swan feathers), and gallantly proposes to take her mentor to the circus and Coney Island. These topics—swan feathers and the circus—sit in the letters alongside discussion of Moore’s strenuous efforts to improve Bishop’s writing and to help Bishop publish it. But there is no sense of discontinuity in this juxtaposition of the personal and professional. By sharing in Moore’s interests in life, Bishop is cultivating her own sensibility, which is the basis of her writing; she is taking lessons from Moore in both. The focus in their correspondence on the articulation of personal taste in all things identifies writing poetry with a way of living, rather than advancement in a profession, which would associate poetry with the utilitarian and self-promotion. What could be further from the purpose of art as Bishop later defined it for Stevenson: “a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration”?

The Bishop-Moore correspondence in the 1930s has the quality of an elaborate game conducted with rigorous formality. It is four years after they begin writing to each other that Bishop addresses Moore as “Marianne” for the first time, and when she does, Bishop writes her friend’s first name in capital letters lit up as on a marquee with dots for electric lights, making it clear that proper deportment is a bit of a joke between them. Yet the question of what Bishop can and can’t say to Moore remains. Tensions come to a head in 1940 when Moore (and her mother, the formidable Mary Warner Moore, with whom Marianne lived) aggressively rewrote a draft of Bishop’s “Roosters,” censoring the poem’s feminist anger and subtle eroticism, and producing a very peculiar poem in the process, titled “The Cock,” as if to challenge the prurient reader to expose his or her vulgarity by finding something off-color in it. In reply, Bishop stood up for her poem and held to her intention to protest the “the essential basesness of militarism.” But her mock-prim manner in response—“What I’m about to say, I’m afraid, will sound like ELIZABETH KNOWS BEST”—threw Moore’s fussiness back on her, rather than rejecting it. As a peace offering, Bishop ends her letter by asking Moore to go to Museum of Modern Art with her. Their game would go on.

In 1947, Lowell effectively replaced Moore as Bishop’s most important poet-correspondent. A pattern is established in the second letter Bishop writes to him. She begins by thanking Lowell for his insightful review of her first book, North & South. While mentioning a “silly piece” by another critic, she interrupts herself in the middle of a sentence, then starts a new paragraph: “Heavens—it is an hour later—I was called out to see a calf being born in the pasture beside the house.” A description of the birth follows, before she turns back to poetry, praising a recently published Lowell poem. Next comes a paragraph on Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where she is visiting. This leads to a paragraph about Lowell’s appointment as Consultant in Poetry to the Librarian of Congress, a second paragraph about the newborn calf, and a last paragraph about Yaddo, the writer’s retreat, where Lowell is currently working and she is writing to him.

The zig-zag movement between subjects and locations charts Bishop’s effort to position herself not only in relation to Lowell but to the poetry world he inhabits. Lowell is in the United States, thoroughly engaged in the business of poetry: publishing poems, writing reviews, taking an official government job in poetry, enjoying a fellowship opportunity. Bishop will benefit from his professional wherewithal: he will help her win prizes and fellowships, and see that she replaces him as Consultant in Poetry to the Librarian of Congress, and much later, that she replaces him on the faculty at Harvard. She looks to him to advise her about how to get on with her career. She admires his poetry (as she puts it in this letter) “extremely.” But she is perfectly ready to interrupt her discussion of it—and to foreground the interruption, not conceal it, as would have been easy, or even easier, to do in her letter—in order to go outside and see a calf being born.

Clearly, she is at best ambivalent about the life of the poet as Lowell is leading it. About Yaddo, she remarks: “I almost went there once but changed my mind.” Instead of the famous retreat crowded with writers and artists, she is writing her letter from a remote village on the shore of rugged Cape Breton, where she is visiting accompanied by Marjorie Stevens (her lover, whom she doesn’t mention to Lowell) in what amounts to a northern version of her teenage Tahiti dream.

Bishop’s letter constitutes an intermediary space between Nova Scotia and the United States, the everyday doings outside her room in Breton Cove and what is going on in the literary culture Lowell is absorbed in. We might think, when Bishop goes out to see the calf being born, she is avoiding poetry, or the discussion of it; and often in her correspondence, Bishop speaks of her interest in travel and daily life, or even the writing of letters, as an evasion of work. In one letter, she speaks of correspondence as “like working without really doing it.” But that is not necessarily the case. The topics in this letter to Lowell that might seem like a distraction, digression, or even an escape from the literary, show her discovering its materials in ordinary life. In fact, the letter looks forward to several poems in Bishop’s future. The birth of the calf is revisited in “A Cold Spring,” the title poem of Bishop’s second collection. The mountainous landscape and other details mentioned in the letter reappear in “Cape Breton,” another poem in A Cold Spring. And that exclamation used as a transition, “Heavens,” turns up again in “Poem,” a late poem (also about Nova Scotia) that adapts the stylistic features of Bishop’s epistolary prose in colloquial free verse.

Bishop and Lowell’s thirty-years-long correspondence entailed a debate about the power and privilege of the poet. On one side was Lowell, who, inheriting the prophetic stance of modernist poets like Eliot, Pound, and Yeats, tried to write like one of Thomas Carlyle’s great men; on the other was Bishop, who was committed to a skeptical, secular poetry rooted in particulars and a “delicate” (her word in “The Map”) poetics of description. Letters hosted this debate, but they did more than that: they were part of it. This was so not only because letters helped Bishop to establish and refine her poetics and sensibility, and to find phrases, images, anecdotes, perspectives, and above all a way of speaking, that she could put to use in poetry, but because questions about the relation between letters and poetry (what these forms have in common, how they are different, and how they should be valued differently) were a focus for broader questions about the relation between art and life that preoccupied both Lowell and Bishop, individually and in conversation with each other.

The climax of the debate is Bishop’s response, in 1972, to Lowell’s book The Dolphin, a work in which he quoted, or appeared to quote, his former wife Elizabeth Hardwick’s letters, which she addressed to him in states of rage and grief after he had left her. Bishop reproved her friend fiercely:

One can use one’s life as material—one does, anyway—but these letters—aren’t you violating a trust? IF you were given permission—IF you hadn’t changed them . . . etc. But art just isn’t worth that much. I keep remembering Hopkins’ marvelous letter to Bridges about the idea of a “gentleman” being the highest thing ever conceived—higher than a “Christian” even, certainly than a poet. It is not being “gentle” to use personal, tragic, anguished letters that way—it’s cruel.

Lowell’s betrayal of Hardwick’s “trust” by using her private letters in his poem, without her approval, while failing to indicate what was hers and what was his—for Bishop, this was simply indefensible. That she found her moral authority on this subject in a letter by Gerard Manley Hopkins was apt. She believed Hopkins had his priorities straight. A “gentle” person is a higher thing “certainly than a poet.” If letters are “an art form or something,” the addition of that “or something” does not mean any less important. Mere art was not worth what Lowell had done. Letters, being on the side of life and art both, were worth more.

Adapted from an essay that will appear in Elizabeth Bishop in Context, edited by Angus Cleghorn and Jonathan Ellis, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Quotations from Bishop’s unpublished letters to Louise Bradley and to Dr. Ruth Foster appear by permission from Farrar, Straus, & Giroux for the literary estate of Elizabeth Bishop, and the Wylie House Museum at Indiana University, where the Bishop-Bradley letters are held, and Special Collections, Vassar College Library, where Bishop’s letters to Foster are held.