Ever since I began covering labor for The New York Times back in 1995, it bothered me whenever corporate lobbyists and conservative spinmeisters used the term, “Big Labor.” The phrase annoyed me for two reasons. First, it suggests that labor is not millions of individual workers—steelworkers and schoolteachers, hotel workers and homecare aides—but rather some insensate, faceless mass that wields brute power. Second, the phrase “Big Labor” implies that organized labor is still big.

It was certainly big in the 1950s, when unions represented 35 percent of the workforce, when labor leaders Jimmy Hoffa, Walter Reuther, and George Meany were household names, and when threats of a nationwide truckers’ or auto workers’ strike spurred a sense of dread among White House officials. But by 1995, labor was no longer so big, and it is even less big today. Just 10.3 percent of American workers belong to unions, and no labor leader is a household name (except perhaps Jimmy Hoffa—thank you, Martin Scorsese and The Irishman for that). The once-mighty United Auto Workers union has shrunk from a peak of 1.5 million members in 1979 to about 400,000 today.

There’s no denying that labor unions are far less powerful than they used to be; indeed, some commentators suggest that they have become irrelevant and obsolete. But many Republican lawmakers evidently disagree; they clearly think unions are far from irrelevant because they’re doing everything in their power to weaken them. The leading example of this came in 2011 when Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker pushed through legislation to cripple government-employee unions in his state.

In a candid moment in 2011, in the wake of Walker’s effort to gut public-sector unions in Wisconsin, his ally Scott Fitzgerald, the State Senate’s Republican majority leader, admitted that a big goal of Walker’s anti-union law was to take out the unions as a financial pillar of the Democrats. “If we win this battle, and the money is not there under the auspices of the unions,” said Fitzgerald, then Democratic presidential candidates are “going to have a much more difficult time getting elected and winning the State of Wisconsin.”

With the Koch Brothers and other right-wing billionaires backing such efforts, GOP lawmakers have moved in one state after another to further weaken unions. In 2017, Iowa enacted a Wisconsin-like law to eviscerate that state’s public-sector unions, while the Republican-dominated legislatures in Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kentucky, and West Virginia have, in the past decade, passed anti-union-fee statutes—euphemistically called “right-to-work laws”—to undermine unions and their treasuries. These laws allow workers in unionized workplaces to opt out of paying any dues or fees to the unions that bargain for and win raises for their members.

Seeing this Republican war against unions, the political analyst Thomas Edsall observed in 2014:

A paradox of American politics is that Republicans take organized labor more seriously than Democrats do. The right sees unions as a mainstay of the left, a crucial source of cash, campaign manpower, and votes… If Republicans and conservatives place a top priority on eviscerating labor unions, what is the Democratic Party doing to protect this core constituency? Not much.

In his 2019 book, State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Businesses, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States—and the Nation, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez explains that when Republicans win trifecta control of a state—that is, the governorship and both houses of the legislature—their first move has repeatedly been to target and weaken labor unions because they know with that powerful adversary hobbled, it will be far easier to enact other parts of their political agenda, such as cutting taxes on the rich and corporations, gerrymandering, or enacting voter-suppression laws. Hertel-Fernandez describes how conservatives do this through a well-coordinated team effort that includes GOP lawmakers, sympathetic billionaires, corporate lobbyists, right-wing think tanks and groups such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), and friendly media like Fox News. Hertel-Fernandez asks why there hasn’t there been a coordinated, countervailing pro-union push.

While many Americans have some notion of the Republicans’ anti-union efforts, many fail to appreciate the political implications of those moves—implications that went a long way toward securing victory for Donald Trump in 2016. Largely as a result of Scott Walker’s anti-union crusade, union membership has fallen at a faster rate in Wisconsin than in any other state in recent years, dropping by 44 percent, or 177,000 workers, since 2008. Trump won Wisconsin by just 22,748 votes in 2016. In Michigan, the cradle of the UAW, Republicans pushed through an anti-union-fee law, along with several other laws aimed at reducing union membership. Because of that legislation and hard times in the auto industry, union membership in Michigan slid by 19 percent between 2008 and 2018—a decline of 146,000 workers, to 625,000. One study found that as a result of Michigan’s new anti-union laws, that state’s ten largest unions cut political spending by $26 million or 57 percent. Trump won Michigan in 2016 by a mere 10,704 votes.

Advertisement

This may not be causation, but it is powerful correlation. As Grover Norquist, the anti-tax crusader who has a side-gig of warring against unions, wrote in 2017: “If Act 10 [the Wisconsin law eviscerating government-employee unions] is enacted in a dozen more states, the modern Democratic Party will cease to be a competitive power in American politics. It’s that big a deal.”

In a 2018 study, labor experts at Boston University, Columbia University, and the Brookings Institution found that anti-union-fee laws caused the Democratic vote share to decline by 3.5 percent in states that enacted such laws compared with neighboring states without such “right to work” laws. That 3.5 percent decline is far larger than Hillary Clinton’s losing margin in Michigan (0.2 percent) and Wisconsin (0.8 percent).

In Pennsylvania, the story is somewhat different. Republicans there have failed to push through any anti-union laws, but battered by the Great Recession, Pennsylvania’s unions have lost 182,000 members since 2008. Trump won Pennsylvania by 44,292 votes. One union member in Pennsylvania told me during the summer of 2016 that while he didn’t buy Trump’s promises to bring back jobs, he still intended to vote for Trump because Trump showed he cared about the troubles that blue-collar families and communities faced.

If all those former members in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were still in unions, then they and their families would have received many phone calls, flyers, and house visits from union members as part of labor’s 2016 campaign efforts. That might have helped offset Fox News’ pro-Trump propaganda. Those workers would likely have heard lots more about labor-related issues to counter Trump’s demagoguery: that Trump, who viciously attacked illegal immigrants, had himself in 1980 used undocumented Polish workers for demolition work when building Trump Tower and then cheated them out of pay; that a candidate who accused China of “raping” the US on trade had his Trump-brand clothes manufactured in China; that a candidate who campaigned as a champion of workers was notorious for stiffing contractors who did work for him; that a candidate who pledged to provide health care to every American at lower cost was actually pushing to repeal the Affordable Care Act and strip millions of health coverage as well as protections for their pre-existing conditions.

If labor’s ranks hadn’t declined, unions might have persuaded hundreds of thousands more workers about the absurdity of Trump’s promises that he would bring back all the jobs and that no factories would close on his watch. (Tell that to the thousands of workers who lost their jobs when General Motors closed its colossal assembly plant in Lordstown, Ohio, last year.)

Some political insiders told me that labor unions didn’t do nearly enough in the 2016 campaign in the Midwest. When I asked several labor leaders about this, they told me their unions didn’t do more campaigning in the Midwest because they—much like Hillary Clinton and her campaign strategists—were confident, indeed overconfident, that she would hold the “blue wall” states of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. (It’s a mystery to me why anyone would be confident about a Democratic victory in Wisconsin in 2016 after Scott Walker had won there in 2010 and 2014.)

Not all union officials were so complacent. Some Service Employees International Union (SEIU) officials told me they, in contrast, were so worried about losing Michigan that they had a bus with union campaign volunteers head to Michigan, instead of its original destination of Iowa. But then the Clinton campaign said they weren’t needed in Michigan and should head to Iowa instead. Some union members from New York told me they wanted to campaign for Clinton in Pennsylvania, but her campaign headquarters told them it would be more helpful to work in North Carolina. A senior Clinton adviser on labor issues told me he had warned campaign officials that things were looking precarious in Wisconsin and that they needed to do more to lock it down. He told me his advice was ignored; indeed, Clinton never even made a campaign stop in Wisconsin after she was nominated.

In retrospect, it’s clear that Clinton didn’t do enough to win over union voters in the Midwest—something that she clearly needed to do because of blue-collar resentment toward her and her husband for having championed Nafta and other free trade measures. I suspect that one reason Clinton gave short shrift to labor in the Midwest was that she had lined up the endorsements of four of the nation’s biggest unions early on—the National Education Association, the American Federation of Teachers, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, and the SEIU—and therefore felt little need to court old-line industrial unions like the steelworkers, auto workers, and machinists.

Advertisement

Those unions, along with the Teamsters, are still strong in crucial Midwestern states like Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Joan Williams of the University of California Hastings, has argued that Clinton came across, first and foremost, as the candidate of, by, and for the professional class, whether lawyers, doctors, or investment bankers—and that many blue-collar voters sensed this and resented it. (Nor did Clinton help her cause with blue-collar workers, many of whom believe the system is rigged, when she gave speeches at Goldman Sachs for $225,000 a pop.)

In 2016, Trump lost the vote in union households by just eight percentage points, the smallest margin achieved by a Republican since Ronald Reagan trounced Walter Mondale in 1984. (In 2012, Mitt Romney lost union households to Obama by eighteen percentage points.)

During the campaign, Trump focused a tremendous effort on winning blue-collar voters. In a move that many such workers loved, Trump attacked the Carrier Corporation in early 2016 over its plans to close its electric furnace factory in Indianapolis, lay off 1,350 workers, and move the operation to Mexico. A month after his election victory, Trump reached a half-a-loaf deal with Carrier; it would keep part of the plant open, retain roughly 700 workers, and receive $7 million in state tax breaks. Trump boasted about the agreement, but many workers and union leaders criticized him for failing to make good on his promise to save all the jobs. Some 600 workers were laid off. Trump deflected blame by attacking the president of the Carrier workers’ union local, saying he had done a “terrible job” representing workers.

After his inauguration, Trump continued to court union members and other blue-collar voters. He invited coal miners to the White House as he began gutting one environmental regulation after another to help increase coal production and the number of coal mining jobs. (The number of coal-mining jobs has failed to grow under Trump after falling sharply under Obama.)

After promising a $1 trillion infrastructure program during his campaign, Trump also invited in construction union leaders, who had visions of hundreds of thousands of well-paying, new jobs building roads, bridges, and tunnels. But Trump failed utterly to get any proposal through Congress, largely because GOP lawmakers have little interest in such big spending plans.

Trump has also courted Richard Trumka, president of the nation’s main labor federation, the AFL-CIO, inviting him to the White House and promising to heed labor’s pleas to revamp Nafta and get tough on trade with China. Trumka said he would “call balls and strikes” on Trump’s performance as president, so he has praised the changes Trump ultimately won on Nafta, while slamming Trump’s push to kill Obamacare and cut taxes on corporations and the wealthy.

“Unfortunately, while he may not even know what his administration is doing, they’ve done more to hurt workers than they’ve done to help them,” Trumka concluded last September. “Our members are still waiting for the supposed greatness of this economy to reach their kitchen tables.”

*

Anyone paying attention to the 2020 campaign can see that the Democratic candidates have learned from Clinton’s loss. In their speeches and platforms, they have focused on lifting workers, especially blue-collar workers. They have backed a $15 minimum wage. They support free community college to make it far easier for blue-collar kids to go to college. They back paid parental leave, paid family leave, and paid sick days—all of which would improve work-family balance.

This year’s Democratic candidates have also apparently gotten the message about the importance of strengthening unions. Not just Sanders and Warren but Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Michael Bloomberg, Cory Booker, Julián Castro, and Beto O’Rourke have all talked of the need to make unions bigger and stronger. They back a raft of proposals to make it far easier for unions to grow—whether giving union organizers greater access to workplaces or increasing penalties on corporations that break the law to beat back unionization efforts, such as by firing workers for supporting a union. These candidates seems mindful of what Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson wrote in Winner-Take-All Politics (2010): “While there are many ‘progressive’ groups in the American universe of organized interests, labor is the only major one focused on the broad economic concerns of those with modest incomes.”

Unions and their leaders have generally refrained from endorsing a presidential candidate during this year’s frenzied series of caucuses and primaries. Many union leaders love Bernie Sanders’s attacks against income inequality, but fear that Trump will bulldoze him in November because so many Americans are turned off by Sanders’s calling himself a socialist. Many were big fans of Elizabeth Warren and her many plans to fix America, but in the months before she quit the race, unions hesitated to endorse her because polls showed that her campaign prospects weren’t bright. Some labor leaders were hoping that Joe Biden would be a vigorous, forceful candidate whom they could rally behind, but many have held off on backing him because his campaign performance has been so uneven and because of his record of championing free-trade agreements.

I’ve talked to union leaders who are hoping for a deadlocked convention that might turn to a unifying candidate with a strong chance of unseating Trump, someone like Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio—a consistent champion of workers and a Democrat who should have little problem winning back Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. In 2018, Democrats showed that they could still win in Wisconsin and Michigan; they captured the governors’ mansion in those states by campaigning on issues that blue-collar voters care about: preserving Obamacare, raising the minimum wage, improving public schools, fixing dilapidated roads.

Some political analysts will no doubt point out that focusing on economic issues might not be enough to win back many blue-collar workers who embraced Trump. Numerous scholars have found that racial attitudes played a bigger role than economic concerns in moving blue-collar whites into the Trump column. In their 2018 book, Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America, John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck wrote that racial attitudes “shaped the way voters understood economic outcomes.” They described this as “racialized economics,” “the belief that undeserving groups are getting ahead while your group is being left behind.” They added that “throughout American history, the groups considered undeserving have often been racial and ethnic minorities.”

Diana C. Mutz, a political science and communications professor at the University of Pennsylvania, found that what drove many white males to back Trump was “not a threat to their own economic well-being; it’s a threat to their group’s dominance in our country over all.” They felt that their privileged status was threatened—they resented the influx of immigrants, they raged against factory jobs going to Mexico, they feared that China’s rise was undermining America’s economic dominance. They liked that Trump railed against immigrants, Mexico, and China. (And many male voters resented that a strong woman like Clinton was seeking the presidency and taking on macho Donald John Trump.)

This racial resentment and misogyny cannot be ignored. Notwithstanding their own dismaying legacy of discrimination against blacks and women, unions are well positioned to help overcome this problem, at least with some voters. In this era of polarization and immigrant-bashing, it is often forgotten that unions, more than any institution other than the US military, have brought together workers from different races, religions, and nationalities (and sexes) and gotten them to pull together. Unions can play another important role. As Ezra Klein explains in his new book, Why We’re Polarized, one reason the nation has grown so divided is that many Americans have been reinforcing social identities that stoke intolerance and push them further toward one end of the political spectrum.

Let’s say a blue-collar voter is a Fox News viewer, an NRA member, and an evangelical Christian, all reinforcing pro-Trump views. But if that voter is also a union member, the information the union provides might help counter those other identities and broaden the views and perspectives that voter is exposed to. (Equally, those individuals can, of course, also bring pro-Trump views to a union and perhaps push it further to the right.)

Union affiliation can help overcome a normally conservative political identity. After the 2008 election, AFL-CIO officials noted that white men overall had voted for John McCain 57 percent to 41 percent, but white men who belonged to unions backed Obama 57 percent to 40 percent. Moreover, gun-owners overall favored McCain 62 percent to 37 percent, while gun-owners who were union members supported Obama 56 percent to 44 percent.

In terms of Trump-era politics, the nation’s unions can be roughly broken into three groups. The major public-sector unions—the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the SEIU, and the two giant teachers’ unions—are squarely anti-Trump. These unions generally have a higher percentage of women and workers of color than the nation’s private-sector unions, and they are generally further left and more social democratic than those unions. The public-sector unions opposed Trump from the get-go, battling his anti-immigrant policies, his assault on Obamacare, Medicaid, and other safety net programs, and his alliance with Republicans who have made it their mission to declare war on government-employee unions.

Then there are the industrial unions, including the United Steelworkers, United Auto Workers, and United Mine Workers. These unions also have some proud social-democratic traditions—the UAW was Walter Reuther’s union—but many of their members voted for Trump. Like AFL-CIO President Trumka, these unions saw good and bad in Trump once he was in the White House. They disliked, among other things, Trump’s war against Obamacare and his anti-union nominees to the judiciary and National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), but they liked his tough talk on trade, tariffs, and reviving manufacturing and mining. Their approach essentially was to criticize Trump on actions they opposed and to applaud his aggressive approach on trade.

The third grouping of unions, the building trades, got closest to Trump, a long-time real estate developer with whom many unions had worked. They loved Trump’s promises of a $1 trillion infrastructure plan, and were wary of doing anything to anger him and risk having the famously vindictive president retaliate by torpedoing his infrastructure plan. Some construction unions even applauded Trump’s support for building new pipelines and his attacks on the Green New Deal, which some union leaders complained might, for instance, slow construction of future power plants (even though it could also mean building many wind turbines).

Heading toward this election, the public-sector unions dislike Trump as much as ever. They’re angry, for instance, that his Supreme Court appointee Neil Gorsuch cast the deciding vote in the 5-4 Janus ruling that will hurt them and their treasuries by making it far easier for government employees to opt out of paying any fees to the unions that bargain for them. They’re also fuming at the recent revelations by the Times that Erik Prince (brother of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos) hired former spies to infiltrate the American Federation of Teachers.

As for the building trades unions, they are hugely disappointed that Trump has failed to deliver anything on infrastructure. In contrast, the industrial unions are thankful to Trump for his trade battles against Mexico, China, and other countries (even as several of those unions’ leaders quarrel with some of his tactics on trade).

Overall, union leaders remain firmly anti-Trump. They haven’t forgotten that the president mounted ugly personal Twitter attacks against Trumka, as well as against the president of the UAW local in Lordstown and the steelworkers’ president at the Carrier plant in Indianapolis. It’s doubtful that the union rank and file is as upset with Trump as their leaders are, partly because they don’t notice and discuss, day in, day out, as many union leaders do, the myriad anti-worker and anti-union actions taken by Trump’s administration.

*

Beyond politics, the nation’s union scene has been shaken up by a surprising burst of labor energy that has taken two forms: a surge in organizing victories in numerous industries and the greatest spike in strikes since the 1980s. Some call this a “new unionism,” a burst of activism, especially among younger workers.

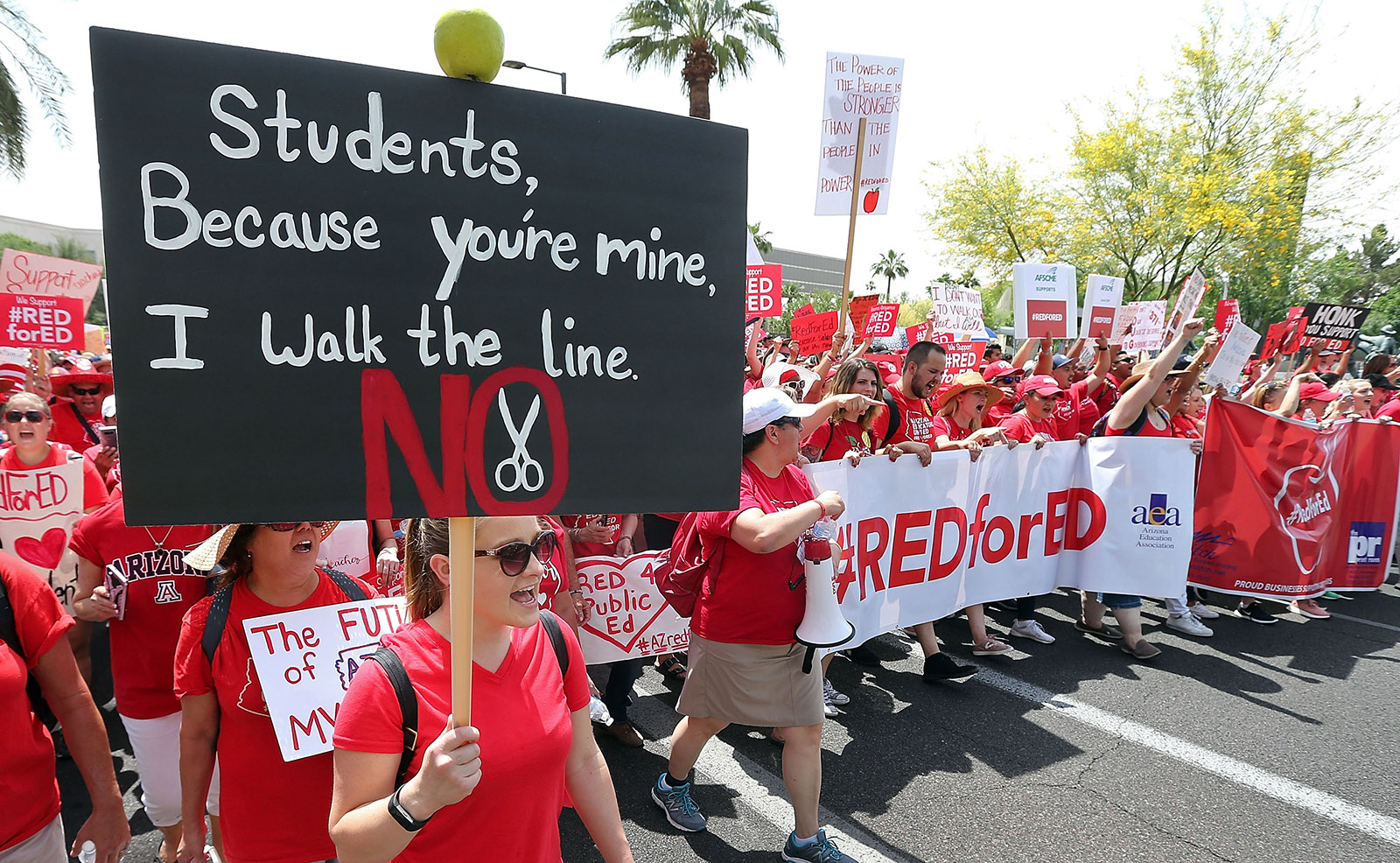

The REDforED educators’ strikes began in West Virginia in February 2018 and soon spread to Kentucky, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Arizona. These walkouts by educators, of whom about 70 percent were women, gave a shot of vigor and inspiration to the broader union movement. REDforED’s successes and fearlessness helped inspire further teacher strikes in Los Angeles and Chicago, along with a walkout by Marriott workers in the fall of 2018, and then, a year later, the six-week General Motors strike involving some 48,000 workers nationwide.

This wave of strikes—especially the REDforED walkouts, which enjoyed tremendous community support—have fueled new excitement about labor, as did the Fight for $15 campaign. This might help explain why public approval for unions has climbed to 64 percent, up from 48 percent a decade ago and at nearly the highest level in fifty years. In other encouraging news for labor, an MIT study found that one in two non-union, non-managerial workers say they would vote to join a union, up from 32 percent in the 1990s.

On a parallel track to the burst of strike action has been an unexpected surge of unionization in fields with little union tradition, among them adjunct professors, digital journalists, museum workers, grad students, cannabis shop workers, even political campaign workers. About ninety contract workers for Google in Pittsburgh have unionized, as have staff at Kickstarter, making it the first well-known tech company to unionize.

All this is promising for labor, but it remains unclear whether these strikes and organizing victories signal a long-awaited reversal in labor’s decades-long slide. Despite the newfound enthusiasm, what’s needed to turn around labor is not just the unionization of ten or twenty thousand workers in nontraditional fields, but the organizing of millions of other non-union workers across the economy. That will be very difficult to accomplish for one main reason: employers in the United States fight harder than employers in any other industrial nation to beat back, indeed quash, labor unions.

Companies in the US repeatedly threaten to shutter plants if workers vote to unionize. They often fire the brave workers who lead organizing drives. They frequently line up friendly workers to spy on organizing efforts and infiltrate unionization meetings. “Employers have perfected the anti-union playbook in the United States in a way that they haven’t elsewhere,” said Jake Rosenfeld, a labor expert at Washington University. Little wonder that unions have pushed the Democratic presidential candidates so hard to get behind legislative proposals that would make it far easier to unionize.

This new burst of labor energy could help make a difference in November’s elections. Much of the surge in unionization, whether at universities, museums, or cannabis shops, is in blue states, so that energy probably won’t make much difference in the presidential election, but it might help keep or flip some Congressional districts blue.

Many teachers’ deep-seated dismay with Republicans—for giving tax cuts to the rich and corporations while clamping down on education budgets and salaries, for championing charter schools while underfunding traditional public schools—helped Democrats capture Kentucky’s governorship last November and Michigan’s governorship the November before. The teachers and other emboldened unions also helped the Democrats win control of both legislative houses in Virginia.

Rank-and-file teachers are so fired up in up-for-grabs states such as Arizona, Michigan, and North Carolina that their energy, their door-knocking, and their phone calls could help flip those states in the Democrats’ favor in 2020 after they went for Trump in 2016. Even so, in bright-red states like West Virginia and Oklahoma, which Trump won by a large margin, it’s doubtful that even an all-out union push would enable the Democrats to capture them.

As I explain in my book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor (2019), to optimize their chances of winning, the Democrats need to formulate a message that appeals to all blue-collar workers, including those who gravitated to Trump, whether out of racial resentment or economic anxiety. If there is one lesson Democrats should take from Hillary Clinton’s loss, it’s that they will have a hard time winning the three key states Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—and with them, the presidency—unless they make a strong appeal to blue-collar Americans of all races, whether it’s a message on trade, income inequality, Wall Street excess, improving health coverage, or increasing workers’ wages.

With blue-collar white voters playing a decisive role in delivering victory to Trump in 2016, Democrats should remember that while it’s vital to fight for African Americans, Latinos, the poor, and immigrants, it’s also important to battle visibly for struggling working-class whites. They, too, need to know that someone cares about them, that someone is trying to lift them up, so that they don’t feel forgotten or left behind.

With Trump bragging that he’s been heroic on trade, unions need to explain that Trump’s much-ballyhooed new Nafta did little to help workers until Nancy Pelosi, prompted by unions, made clear it wouldn’t get through Congress unless the president got Mexico to agree to stronger enforcement of labor rights. Unions can also explain that Trump badly botched his trade showdown with China by going it alone, instead of having our allies—Canada, the European Union, and Japan—at our side to maximize bargaining leverage against China.

Many union members welcome information from their union, even as many resent it if their union heavy-handedly tells them whom to vote for. Unions can play a vital role in the 2020 campaign by explaining to their members that Trump has been not nearly the champion of workers he claims to be—and has, in fact, betrayed workers time and again. Unions can help make clear that while the jobless rate is low and the economy has been in fine shape (at least until the coronavirus outbreak), that’s in large part a continuation of the improving economy that Trump inherited from Obama.

Unions need to trumpet loud and clear how Trump and his appointees have rolled back the Obama administration’s decision to extend overtime pay to millions more workers. Trump has given huge tax cuts to corporations and the wealthy, but peanuts to average workers. He has pushed to strip millions of working families of their health coverage by seeking to repeal the Affordable Care Act. He has made it easier for Wall Street firms to cheat workers by scrapping an Obama rule that required investment firms to act in workers’ best interests when managing their 401(k)s.

His NLRB appointees have moved in myriad ways to make it harder to unionize and to weaken protections for workers who engage in collective action—proposing, for example, to take away the right of graduate teaching assistants at private universities to unionize by declaring that they are not to be considered workers. He has reduced the number of OSHA inspectors to the lowest level in the agency’s five decades. And he has done nothing to lift the federal minimum wage, which has been stuck at $7.25 an hour for over a decade.

Trump is a conman nonpareil who has fooled millions of workers into believing he is their champion. No institution in society is better positioned than organized labor to disabuse workers of that demagogic notion.