This running series of brief dispatches by New York Review writers will document the coronavirus outbreak with regular updates from around the world.

—The Editors

Anastasia Edel 🔊 • Eduardo Halfon 🔊 • Tim Parks • Miguel-Anxo Murado 🔊 • Ruth Margalit 🔊 • Sarah Manguso • Mark Gevisser 🔊 • Simon Callow 🔊 • A.E. Stallings • Rachel Pearson • Vanessa Barbara • Ian Jack • Elisa Gabbert 🔊 • Christopher Robbins • Lauren Groff 🔊 • Anna Badkhen 🔊 • Joshua Hunt 🔊 • Anne Enright 🔊 • Madeleine Schwartz 🔊

Madeleine Schwartz

March 22, 2020

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK—I am a reluctant biker, but on Monday night I rode from downtown Brooklyn, where I live, to upper Manhattan, where my mother claimed to be having trouble downloading Skype. The road was empty. Two finance bros discussed going to “Nick’s aunt’s townhouse in South Beach.” A few joggers retreated into their AirPods. There were no children on the street.

The western length of Manhattan is lined with thousands of apartments worth millions of dollars, most of them built with big glass windows facing the river. I did not see a single face looking outside. At 34th Street, I craned my neck to try to see The Shed, the Michael Bloomberg-backed performing arts space inside a luxury mall. It had occurred to me that it might serve as a good makeshift hospital, with its $27 million skylights letting in the sun. (The next day, Bloomberg pledged $40 million to coronavirus relief efforts.) In the West 60s, a single FedEx truck was driving along the road formerly known as Trump Place.

Since the beginning of the year, I have been editing a site with dispatches from every 2020 election that isn’t the United States’. Over the past few days, a number of my writers have emailed to reluctantly pull out: the elections in their countries have been delayed or postponed, occasionally indefinitely. Coronavirus is the reason given. We see pictures of police across Europe ready to fine citizens for unauthorized walks, while the hospitals complain of a shortage of personnel.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the federal government, which has done little to implement life-saving tests, is entering talks with the data analytics and intelligence contracting company Palantir about coronavirus-related surveillance. A friend of mine was recently told to go back to China. Should we be surprised if this illness leads to further cruelty? Already, we see it as an excuse for increased authoritarianism around the world. Any historian will tell you: after the plague, the pogrom. ■

Anne Enright

March 22, 2020

DUBLIN, IRELAND—On March 11, the day Donald Trump addressed the nation about Covid-19, I was in the middle of a book tour (the show must go on!) in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. I’d made the decision to travel from Ireland when there were six reported cases of the illness in New York State, and the odds seemed good to me.

The situation changed as I traveled, but not much. I was less than enthusiastic about the man in New Hampshire who attended a “mixer” party after testing positive, and actively disturbed by the news from Dublin, my hometown, that employees of Biogen in Ireland had been urged to empty its office there, after the company’s conference in Boston had been linked to dozens of cases. The morning after Portsmouth I was due to go read in Cambridge, Massachusetts, four miles from their conference hotel, so I had the odd feeling that I was moving in the wrong direction.

After my reading, I went back to the hotel and wasn’t bothered watching Trump, so it was forty long minutes before I realized that he had switched from denial to what seemed, to me, to be an arbitrary act of xenophobia: he had just banned all travel from Europe to the United States. I did not yet know that when he said “Europe,” he did not mean the English-speaking countries of Great Britain and Ireland; perhaps they were not, in his mind, “foreign” enough. I picked up my European passport, went down to the bar and ordered a glass of wine and looked up flights to Ireland on my laptop, with one ear on the TV screen and another on the three people sitting near me on high stools. A local couple and a lone female traveler; they had been brought together by the immediacy of the subject, and they had views. I can’t remember what these views were.

Their conversation now seems to belong not just to another time but to another model of the world—one in which, among other things, people thought their opinions mattered. I deal in words for a living, but I have had difficulty forming them, since that moment, whether to describe or analyze. I don’t really understand them anymore. I understand touch, breath, contact. I understand plane tickets—I booked one as the price rose under me, the morning after Trump’s address. I took a car toward Cambridge and turned left for Logan airport. I understand the word “home.”

Advertisement

I had considered the numbers, as though they were real and meant something—I forgot you have to collect them first. The US was not testing people, because America values private medicine over communal health. That is why the numbers were low, because Trump said, “I like the numbers being where they are.” I don’t even have the wherewithal to feel stupid about all this. I cannot find a tone. ■

An earlier version of this post misidentified the date of the author’s visit to Portsmouth and President Trump’s address to the nation; it was March 11, not March 12. The post has been updated.

Joshua Hunt

March 22, 2020

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA—Sometime around the end of the first week in February, I woke up to a familiar sort of buzzing from my cellphone—a distinctive burst of noise and vibration that brought to mind the mobile alerts for an earthquake in Japan, where I worked for several years as a foreign correspondent. In this case, the buzzing signaled a different kind of disaster: new Covid-19 infections.

The first one was distressing, but for days afterward, the slow trickle of alerts that followed it was almost reassuring: stray noises, disconnected from the steady, destructive rhythm of the virus, which had by then infected well over 50,000 people in China. If the buzzing signaled anything, I thought, it was that Covid-19 had found no momentum in South Korea.

Then, on February 18, these intermittent alerts started coming in constant, angry bursts. In Daegu, a city just north of Busan, a member of the Shincheonji Church had tested positive for the virus; the dozens of people she’d infected at her church and at buffet-style restaurants where she dined had subsequently infected hundreds more, who in turn infected thousands of others. In a matter of days, the alerts were coming so frequently that the noise faded into the background of daily life, like the sound of cicadas in the summer.

I soon disabled these emergency notifications, but by then the entire city was a warning. At the grocery store, a sign posted at the entrance warned shoppers that an infected person had been there days earlier, and that anyone who had been in the store on that particular date should be tested. Few people left their homes without wearing a surgical mask, and aside from pharmacies and grocery stores, most businesses were left empty.

When I ventured to a nearby restaurant for takeout, I paid by passing cash through a small hole in a clear plastic sheet that hung from the ceiling to the floor. Afterward, I cleaned my hands using the sanitizer that sat on a table near the entrance, and on my way home cleaned them again using the bottle of sanitizer that had been placed in the elevator of my building.

This upending of normal life happened almost overnight, and with very little prompting from the government. There was no need for curfews or lockdowns, and I had little sense that people were afraid. What was it, if not fear and panic, that had motivated so many people to dramatically alter their daily routines? The answer, I think, is quite simple: information.

South Korea’s government, which learned many hard lessons during the deadly SARS outbreak in 2003, launched a swift investigation into Covid-19’s progress in Daegu. The subsequent flurry of government testing for the virus allowed investigators to quickly identify and quarantine infected people and screen everyone they’d been around. Instead of inducing helplessness and complacency by telling the public what to fear, the government produced a steady stream of data that told them what they could do to protect themselves.

By the time I left for work in Tokyo a few weeks ago, things had improved so dramatically that I felt uneasy about leaving South Korea. But the assignment was important, so I switched the emergency alerts on my phone back on, and boarded my flight. So far, Japan seems to have outrun the virus, but in the absence of widespread testing, it’s hard to say for sure. For now, all I can do is wait for that familiar sound. ■

Anna Badkhen

March 21, 2020

LALIBELA, ETHIOPIA—I came to Ethiopia for book research that has to do with displacement and Eden, and tracing our beginnings as humans. How could I have known that the trip I had meticulously planned for months would be so ill-timed, that the world would be so anxious about endings?

I left the United States when coronavirus cases seemed localized in California and New York, but hand-sanitizer was already gone from shops. The day I landed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia confirmed its first case of coronavirus.

A bellyful of worry increasingly accompanies my quest to contemplate our origins, the history of our relationship with place, and human movement, ancient and modern. On my second day in Ethiopia, at a paleontological site, I stood over the place where researchers had found the fossils of a 4.2-million-year-old Australopithecus, who preceded Lucy by a million years. I moved on to the nearby fossil field of homo sapiens remains dating back 160,000 years, where passing camel herders draped their arms over their Kalashnikovs and asked news of the coronavirus. So did the women in the nearest village, where I overnighted in a reed hut. I fell asleep wondering: What did the Herto Man, our direct ancestor, who had lived here once, fret about?

News from America: my child’s university transitioned to virtual classes, and the students, displaced, must leave their dorms. I drove northward, past posters warning in Amharic against the perils of illegal migration. Thousands of impoverished Ethiopians try to reach Arabia and Europe each year, often by sea: the exodus from Eden continues. I spoke to young men my child’s age who had crossed the Gulf of Aden to Saudi Arabia and were deported, even younger men who say they will try to make the crossing again, others whose friends have died on the journey. I could not reach my child: my US phone has no cell coverage here. When I stopped for the night at a roadside hotel, there was no Internet, and the bellhop explained that it had been turned off to contain coronavirus rumors.

The disease is spreading quickly; panic spreads quicker. The government has confirmed more Covid-19 cases, and the US embassy in Addis has posted a security alert: foreigners in Ethiopia have been violently attacked because they are believed to spread coronavirus. In coffee shops, men watched coronavirus standup comedy on their cellphones. I drove through towns where health workers were demonstrating hand-washing techniques to passers-by at busy intersections. All schools have closed for fifty days. In America, my child has found shelter at a friend’s home.

In Lalibela, where a twelfth-century Ethiopian king hewed churches out of mountains, twelve pilgrims died this week in a bus accident, and I arrived in a town flooded by thousands of mourners in white. My worries felt petty. Then I learned that it was unclear how much longer Ethiopian Airlines, the only transportation by air still available, would be operating international flights. I was supposed to stay for three weeks but changed my ticket, losing a week of research. I panicked and tried to rebook for an even earlier flight, but the Internet connection was too slow.

What to do? I hiked up to Asheten St. Mariam, a monastery carved into the face of a cliff, 13,000 feet above sea level. The monastery church is older than the Black Death, older than the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima. I think of how the pandemic exposes our aspirations and dread. I think of the entire history of human strife and how we navigate the frightening and the unknown. I think of how I will get back, but the concept of “back” feels vertiginously spectral. ■

Lauren Groff

March 21, 2020

GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA—This is the seventh day of our self-sequestering in Florida. Our antique neighborhood, normally swarmed with children on bikes and on foot, has gone eerily still. From the porch, thick with pollen, we hail our neighbors walking their dogs, and over a safe distance from sidewalk to porch, we shout about catastrophe, pandemic, toilet paper, stock markets. People in this section of town are mostly affiliated with the University of Florida and have taken radical precautions, but we hear from those who still go out to work that other parts of town are nearly as normal.

I find I have to run very early in the morning to avoid the crowds of blithe young people who cluster on the grass in the parks, exposing their flesh to the sun. I am not their mother, so I don’t yell at them to protect themselves the way I want to. At the same time, I find myself sympathetic; we are all dreading the heat that we can feel gathering itself, about to crash down in a week or so. Too soon we will be forced to estivate, to draw the shades against the sun searing through the windows and live our days in gloom; we will go out only when it’s cool, in the early morning or after sunset. Pandemic claustrophobia will arrive.

My normal life is the life of a shut-in, as a writer with no other job, and for me this time has been disconcertingly social. One of the concessions my husband granted in exchange for making me live in Florida is that I can go straight to my work in the morning without having to deal with, hear, or even set eyes on my children. Now that they are away from school, I find myself with company all day, scrambling to keep my boys busy. I have been leading a daily writing workshop on Google Hangouts for the neighborhood kids, and I’m struck by how easily the under-twelve crowd picks up ideas that are hard for graduate students to understand.

I wake every morning to an email by a group of beloved writers, each taking turns sending poems they have recorded in their own voices, to keep morale up. Different clusters of friends have daily cocktail hours online. I’m reading Don Quixote in a book club with two brilliant novelists. My days, generally empty of others until my boys come home from school, have become nearly too full with other people. Perhaps I am over-sating myself, in fear of loss.

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

The only thing to do to escape the prison of these fears is to immerse myself in other people, to pull the bodies of my boys close, to sink into the minds of the writers I’m reading, to love the faces of family and friends visiting by computer screen. And to sit in the relative coolness of the morning, now, listening to the birds newly arrived from South America in the magnolias, knowing it’s the last of the gentle weather we will be having for a very long time and trying not to think about the misery to come. ■

Christopher Robbins

March 21, 2020

NEW YORK CITY—How do you tell New Yorkers to forget about the culture and booze and laughter and food and people that make this city worth living in, and go back to their tiny, overpriced apartments and stay there, alone? Some wind or snow would help, but last Saturday there was nothing but vague warnings from politicians that we should keep a safe distance from one another, which sounds like advice from someone who has never been to New York.

“I’m waiting for the government to tell me I should be more concerned,” one woman standing outside of a bar told me that night. Who was being absurd: the person going out for a drink in Lower Manhattan on a Saturday night or the reporter standing six feet away, wearing gloves, wincing at every tiny fleck of spit arcing out of his subjects’ mouths?

Less than twenty-four hours later, the government spoke, shutting down schools, restaurants, bars, and cultural institutions. A second wave of panic-shopping ensued. Men with sheepish grins noisily lugged boxes of beer away from bodegas and Trader Joe’s cut their hours for everyone’s safety.

Now, five days into the de facto quarantine, us lucky ones sit at home, sharing graphs and charts that map out New York’s rising number of cases and deaths against those in China, Italy, Iran. “I am the ghost of Christmas Future,” I texted my friends and family in Virginia. “This is not a joke. Tell your parents to stay inside.” My mom, who used to make me open doors at the mall for her, called to ask if she could take a walk with a friend who had been exposed to someone who had tested positive for Covid-19. It was “at a huge party,” and she assured me they would walk in the road, six feet apart. “Please don’t,” I told her. A few hours later, I’d be in a grocery store, exposing myself to the outside world for some chocolate and fresh produce.

On a normal day, my job as a reporter for Gothamist is to take in reams of information from interviews, social media, and public officials, and synthesize it in a way that is readable and understandable. Now there is too much information to process, and nearly all of it is almost comically depressing. Nurses call and tell you how their hospitals are overwhelmed. People with loved ones in prison describe confusion and fear. People in hospital gowns post videos to Twitter describing their symptoms. Your friends in the service industry lost their jobs. The owners of a local bar say they may not be able to reopen if and when this all passes. The governor tells me that everything has forever changed. I take my temperature a few times a day, re-reading the thermometer’s flimsy paper instructions to give myself some semblance of control, still unwilling to submit to a more accurate, rectal application, but it’s early yet.

Much has already been written about the rejuvenating effects of taking a walk, and this is partly true. There is the sun, here are delivery workers unloading mountains of packages or flying down avenues on electric bikes to bring someone food. A man behind the wheel of a slinky Mercedes waits for his fare on the Upper East Side wearing sunglasses, gloves, and a mask. The J train still clangs across the Williamsburg Bridge. New York City is still here.

But these same signs can feel ominous, or ridiculous. Why are some people risking their lives ferrying goods on the street while others are snug, forty floors above? Are those people in the park really playing Quidditch right now? A playground writhing with children in sixty-degree-weather feels downright sinister. I walk up six flights, rub disinfectant on my keys, scrub my hands, and fire up the Metropolitan Opera’s free stream. I’m told there’re too many people trying to access it now, and I have to wait in line. ■

Elisa Gabbert

March 20, 2020

DENVER, COLORADO—I haven’t left our apartment, except for the occasional walk or run outside, in twelve days. I haven’t been in a public indoor space. The Sunday before last, my husband heard that someone at the high school a few blocks away had tested positive for Covid-19; the school is across the street from our gym, and it’s full of students when I usually go, in the late afternoon. Well, I said, I guess we have to stop going to the gym. He had a few writing classes he still needed to teach in person, so every time he left the house he stopped for more groceries.

Even so, he worried that we didn’t have enough, so on Monday he got up early and went to Whole Foods right when it opened. He came back visibly shaken by the experience, the atmosphere of panic. The store was so crowded people kept bumping into him, so at home he immediately threw all his clothes in the wash and got in the shower. Unpacking the groceries, I felt like crying. He’d gone without a real list, since we didn’t know what they would have. I felt like I was opening Chopped baskets full of random, exotic treats—bison steaks, miso broth, fresh halibut. He even thought to get tomato paste and a backup jar of mayonnaise.

Cooking is the only time I feel normal. I made a curry with the halibut, and topped it with the last of a bunch of fresh mint we had in the fridge. The next night I made pork chops, grits, and kale, and the following night I made a hash with the leftover pork. There’s something pleasurably game-like about figuring out what to cook every night, starting with whatever’s most perishable, limiting what I take from the freezer or pantry, incorporating scraps or a bit of sauce from previous meals, recursively. We’ve been eating well, so far, at least.

Last summer I heard the writer Chris Castellani talking about a character in his novel that he’d based on a friend. This friend was known to talk to his parents every day, and when people asked him why he did that, he’d say, “Because they’re still alive.” I’ve thought about that a lot, and in the past several weeks, I’ve started talking to my parents every day. My mother turns seventy this year, a few days after my parents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary; we were planning a family trip this summer to celebrate. We’ll probably have to cancel it, but we’re waiting until the last minute. My mother is about as high-risk as it gets, so I’m relieved that she is taking the virus seriously. Unfortunately, my father, a doctor, is still seeing patients. He feels that he can’t just abandon them. Many are elderly; a few have begged him not to retire before they die. Today he finally agreed to shut the office for two weeks. It will certainly have to remain closed longer.

I’ve been having a feeling, on and off, that I can’t describe—my inability to name it is its most distinguishing feature. I can’t decide if the symptom is confusing or confusion is the symptom. I feel it mostly in my head, but it isn’t a headache. It doesn’t exactly hurt. I sometimes say, My nerves are bad, as in The Waste Land. It’s appropriately vague. I sometimes say it hurts because that’s easier. I wish it were pain, in a way—being able to describe how I feel is a comfort, while not understanding produces a meta-anxiety. In a way I’m expanding my idea of pain, to include this new namelessness. ■

Ian Jack

March 20, 2020

LONDON, ENGLAND—“One doesn’t normally take seriously what Boris Johnson says, but on this occasion there may be something in it,” my friend wrote earlier this week, canceling a party for his seventy-fifth birthday. Those of us above seventy are all self-isolators now. Johnson has told us we can expect to “lose loved ones,” the loved ones in question being mainly our elderly selves and people with—a now familiar phrase—“underlying health conditions.” He doesn’t say, “Some of you are going to die soon,” presumably because it sounds too frightening and medieval, like Death in The Seventh Seal. I have to admit that Johnson doesn’t look too good himself. Frankly, he looks scared and out of his depth. Being prime minister wasn’t supposed to be like this. It was meant to be a kingly occupation in which he could forever exercise his irony and good cheer and make his subjects laugh.

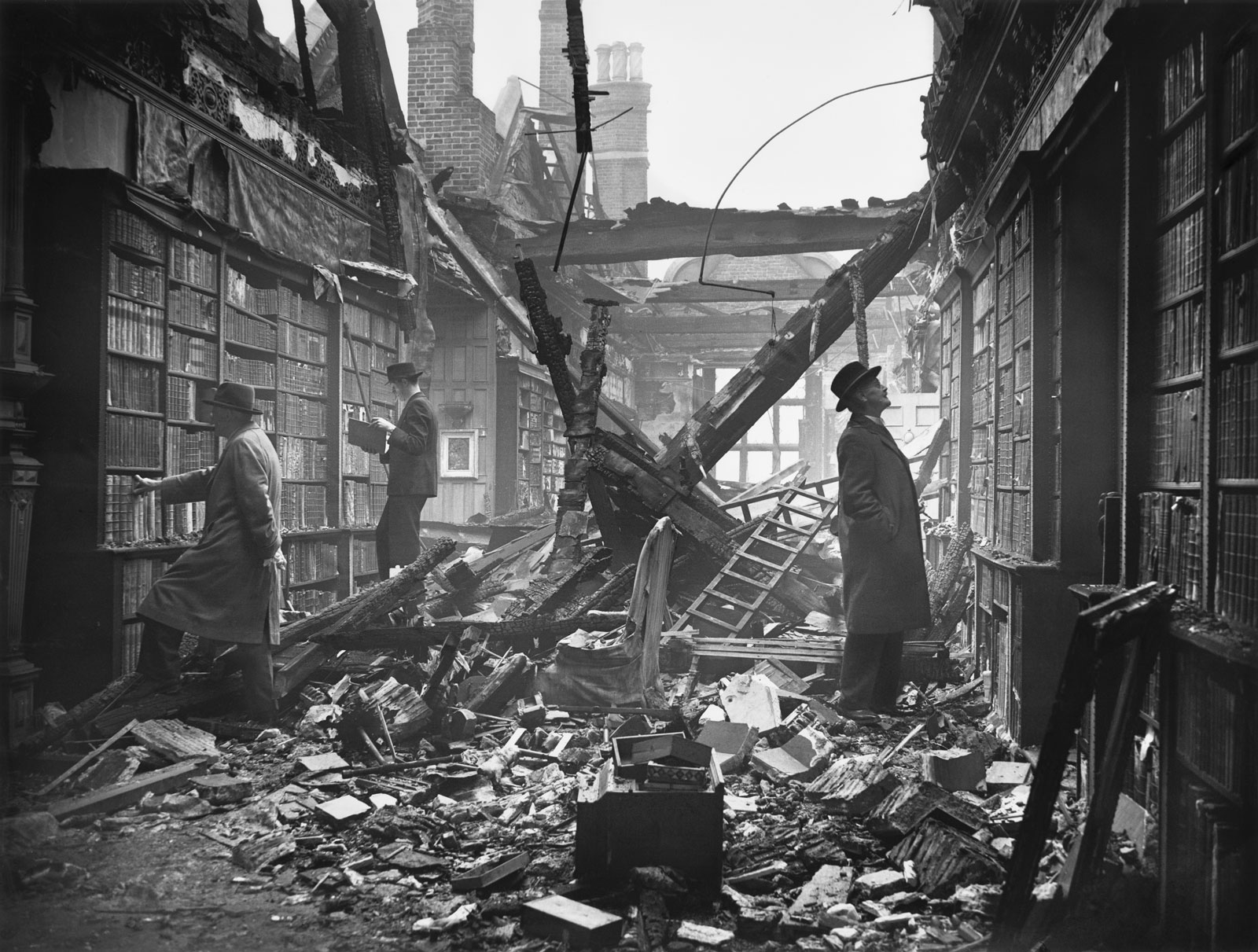

Inevitably, the spirit of the London Blitz has been invoked. On a recent news show, an American professor spoke generously when he said the stoicism that flourished in wartime Britain would surely see us through a pandemic. Americans, of course, were the audience for which the Blitz spirit was bottled and labeled. Humphrey Jennings’s brilliant ten-minute documentary London Can Take It! made the leading contribution, with its portrayal of ordinary people coping with terrors of aerial bombing in the autumn of 1940—old people sleeping in air-raid shelters, commuters picking their way through the rubble, scenes that were prefaced by the tell-it-like-it-is voice of the American broadcaster Quentin Reynolds: “I have watched the people of London live and die… I can assure you, there is no panic, no fear, no despair in London town.” The US had yet to enter the war. The film was finished in ten days and swiftly dispatched across the Atlantic, where a private screening was arranged for FDR. In the estimate of Jennings’s biographer, Kevin Jackson, it remains “one of the few films that have played some small part in changing the course of history.”

London wasn’t quite as heroic as the film suggested. Londoners were scared: Why on earth wouldn’t they be during a bombing campaign that killed 20,000 of them in the space of eight months? But it isn’t hard to believe that there was then a greater sense of public order and personal restraint—behavior that seems to have receded in the eighty years since. Panic-buying over the last week has emptied the shelves of British supermarkets for no good reason (there is as much food as ever), prompting squabbles in the aisles and the introduction of special opening hours reserved for the old and less fit. How shaming, then, at least for a certain British generation, to learn that in the virus’s new epicenter, Italy, citizens have behaved impeccably, buying no more than they need and singing Puccini from their Florentine balconies to entertain their quarantined neighbors.

A puzzle in all this is the mania for toilet-paper rolls, purchased in bulk, not by large hotels and prisons, but by people who look as though they live like the rest of us—in one house with, at most, two lavatories. Pictures show supermarket trolleys heaped high with them; disappointed customers complained that they couldn’t be had “for love nor money.”

It may be that some folk memory of an intimate difficulty has been awoken: the great toilet-paper shortage of 1944. An obvious benefit of self-isolation is that it gives you much more time to read, and this week I’ve been reading Norman Longmate’s account of civilian life in World War II, How We Lived Then, published fifty years ago and perhaps never read properly by me before. Longmate records that the shortage was severe enough to be raised as a question in the House of Commons, and for out-of-date office files to be commandeered as a substitute. A Surrey housewife said that she “loathed the indignity of entering a public lavatory and being asked whether I needed paper. I always tried not to need it and so appear mutinous.”

Many shortages persisted, and in several cases worsened, in the years after the war, but toilet paper was not among them. I grew up in a well-provisioned household, unlike my wife, who remembers pages of the Newcastle Evening Chronicle hung from a nail. We talked about this the other night: the reveries of self-isolation. ■

Vanessa Barbara

March 20, 2020

SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL—Over the last week, a powerful virus has been circulating among the toddlers in my daughter’s public nursery school. She spent two nights with a high fever and many others with a persistent cough that caused occasional vomiting. (She’s twenty months old.) But this happened a few days before the coronavirus started to spread locally in Brazil, so her pediatrician guessed it was common flu or something similar. Besides, many schools here are registering a number of H1N1 and Influenza B cases, which are also possibilities. I was eventually infected, too. We didn’t take any tests.

At that point, the country had registered two hundred confirmed cases of coronavirus and almost two thousand cases under suspicion. There was no countrywide confinement.

On Monday, when my husband went by the nursery school to deliver a sick note, the teacher casually mentioned that there were three confirmed coronavirus cases there. He immediately went home and broke the news. I was alarmed. My daughter apparently found the word funny and she couldn’t stop repeating it: “Co-ona-visss! Co-ona-visss!” while running in circles in the living room. (She was feeling a lot better.)

To be completely sure, I called the school. They said those were only suspicious cases. We stayed home, as we’ve been doing for a while now. My husband went to work, wondering when he would be allowed to do his job remotely. (He’s a tax inspector for the city hall.)

In Brazil, denial and confusion are the current official strategies to deal with the pandemic. President Jair Bolsonaro has been downplaying the crisis for weeks; he had called concern over the virus “oversized” and said that “other flus kill more than this.” On March 15, the president joined a pro-government street rally in Brasília, ignoring medical recommendations of social distancing. He shook hands and took selfies with supporters. More than fifteen members of his recent delegation to Florida have now tested positive for the virus.

On Tuesday, against all better judgement, a few of my friends gathered to play volleyball as if nothing was happening. Meanwhile, health officials reported Brazil’s first death from Covid-19. By then, the country already had three hundred confirmed cases. But we know these statistics are unreliable: almost no one is being tested for anything, after all.

On Wednesday, my friends decided to play volleyball again. Seriously. The death toll rose to four people, all of them from São Paulo. The mayor ordered the shutdown of all commercial establishments—including volleyball courts—with some exceptions such as supermarkets and drugstores. My husband was finally allowed to work from home. I had a low fever. My daughter seems to be recovering well.

On Thursday, I received the news that my daughter’s best friend, from the nursery school, is also on the path to full recovery—we only don’t know exactly from what. In Brazil, against the recommendations of the World Health Organization, only patients with severe symptoms of coronavirus are being tested. Streets are finally starting to empty out a bit. Death toll: seven.

It seems that the denial phase is almost over. Now we can concentrate on isolating ourselves with confusion as company. ■

Rachel Pearson

March 20, 2020

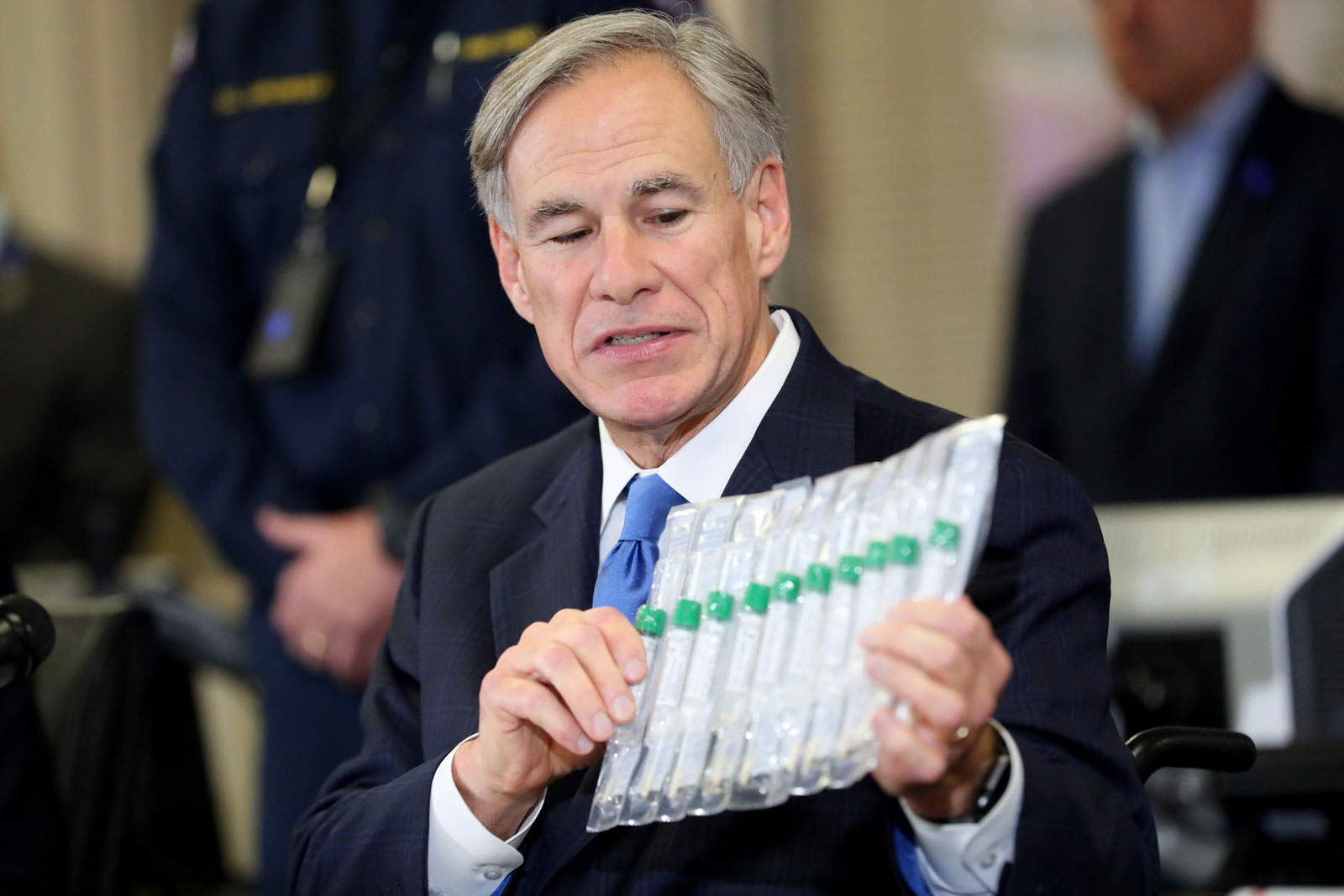

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS—Today they began checking our temperatures on the way into the hospital. Two women in scrubs and masks stand at the entrance to the skybridge that connects the employee parking garage to the hospital, brandishing forehead thermometers. “97.2,” one tells me. My temperatures have been running a little lower than average, because I’m pregnant. I walk on, and a colleague of theirs (also in a mask) asks if I have had fever, cough, or shortness of breath, or if I have been exposed to anyone known to have Covid-19 “outside of work.”

I haven’t.

It is Texas, and we’re civil, so I thank the screeners for their work and one says, “Oh my gosh, thank Y’ALL!” and the other asks if she can touch my belly before she puts the sticker on my hospital badge indicating that I’ve been screened today.

“Go ahead,” I say. “My scrubs are clean.” I have just begun to feel my son kicking, but you can’t feel the kicks from outside. Even so, the lady smiles when she touches my body.

“Your first?” she asks.

“My first,” I say. We both use hand-sanitizer before I move off down the skybridge, pulling my white coat on. At one time, I imagined that I would hate being touched like that, or stared at, but now I am glad for the moments of joy that spark off around my pregnancy. The pandemic is mounting, and we doctors who practice in the cities that have been spared so far imagine that our days of ease are numbered. San Antonio is warm and humid and sprawling, but it is not isolated; the new coronavirus will come for us, too.

Even so, it’s a relief to be inside the hospital, where everyone knows what to do with themselves. The nurses on the pediatrics ward still argue with my residents over which baby needs an IV placed; the pediatric gastroenterologist leads his gaggle of learners, reduced by two since the medical students have been sent home. Infants with jaundice lounge under blue lights, while in other rooms toddlers shiver from flu. We all worry a bit about our patients with medical complexity—the kids with odd-shaped hearts, the ones who have tracheostomies and feeding tubes and seizures that break through all the medicine to leave them shaking on the floor. How will they weather Covid-19?

The normalcy on the pediatrics ward has a summer-camp feeling, as if the sky will break open soon. Soon we may be pressed into other kinds of service—adult medicine, or ICU medicine, or whatever is most needful. I may be sent home for being pregnant; I may be called back. By most estimates, the fatalities will have peaked by July, when my son is due to be born. I will deliver at this hospital, the one that is familiar to me, and the pediatrician who cares for my son in his first days of life will be a friend.

But for all my friends in medicine, especially those in the ICU and adult medical wards, how much suffering lies between us and July? Will we go the way of Lombardy, where an estimated 20 percent of healthcare workers became infected? Or will this country pull it together, get us the masks and gowns and test kits and ventilators and back-up we need to save not only our patients’ lives but our own?

Every hospital has ghostly places, rooms where the dead kids gather to sing from empty beds. I yield little ghosts their swaths of air, but I do not want their song to swell into the hallways, to slip past the lips of my friends and fill their lungs with noise. I want us to all survive through summer, though I know that is probably a silly wish, one any child would make. ■

A.E. Stallings

March 19, 2020

ATHENS, GREECE—It started at the end of February with the unheard-of cancellation of Carnival. Clean Monday weekend in Greece—March 2 this year—marks the culmination of Carnival and beginning of Lent. (Instead of a penitent Ash Wednesday, Orthodox Lent begins with a cleansing meatless feast of pickles, salads, and seafood, punctuated with the flying of kites.) My husband and I and our two kids, now fifteen and ten, usually leave Athens for the long weekend and head to a nearby Saronic island off Aegina, where we rent a place. I thought the island might defy the ban, surely meant for large-scale parades, such as in Patras. But the island had taken it seriously. My daughter’s Pokémon Pikachu costume was never taken out of the suitcase. (I had passed up a child-sized Venetian plague doctor costume at the shop.) Restaurants were still open, and one kite hung in the sky.

We returned to Athens later on Monday only to find our children’s school was connected to a case of Covid-19 and would shut down. We did our online lessons—my son’s high school class even took attendance, while the elementary school had a series of online games and homework pages—with that light snow-day sense of nonoccasion, and then went to play basketball at the empty court in the spring sunshine. Two days later all schools were closed. There were runs on face masks and anti-bacterial wipes. When my friend John Tripoulas, a poet and surgeon, was preparing to operate at the public hospital where he works, he discovered all the face masks were gone—no doubt flogged on the black market. Luckily, a nurse had kept a private stash.

As anxiety and the number of cases increased, I was somewhat appalled to discover that my elegant and redoubtable but rather frail eighty-eight-year-old mother-in-law had gone to the hair salon to get her hair done. In retrospect, maybe it was foresight; salons were shut indefinitely the next day. Having lived through the German invasion, famine, civil war, and the Junta, she planned to be well-coiffed, whatever came next.

Now—just as the Greek economy was turning around—cinemas, bars, restaurants, museums, archaeological sites, and seasonal tourist accommodations are closed and cruise ships forbidden. The country’s land borders with Albania and North Macedonia have been closed and all borders are entirely shut to non-EU nationals, flights to Spain are halted, and other arrivals to the country must self-quarantine for two weeks. Church services for all religions are suspended, except the necessary—that is to say, funerals, with limited attendance.

Rumors swirl that an internal travel ban will be next, closing roads out of Attica toward the countryside and sea routes to the islands. (Athens is the major disease vector—just ask Thucydides.) Not wanting to be stuck in town, my family absconded on March 13 (Friday the 13 is not unlucky in Greece—that’s reserved for a Tuesday), including the rabbit and the cat, back out to the island, where we can wait out the virus with a view of the sea, the main nuisance being gangs of feral peacocks and slow internet connections for online lessons. The grocery stores here are still open, although a new law requires that customers stagger their entrance, and we’ve stocked up on essentials: lentils, beans, pasta, and wine. We ferried quantities of olive oil, milk, and eggs from Athens; in a pinch, we know people here with laying hens.

Of course there are drawbacks to our remoteness. While Athens hospitals were already stretched thin by brutal austerity before this new crisis hit, the island does not even have a doctor. Islanders rely on the pharmacist to dispense medical advice, veterinary and human, when they cannot reach Aegina or Piraeus. If one of us fell ill, would we be able to get back to the mainland? I write this during an island brownout, sure to become more frequent, hoping my computer will hold its charge till electricity comes back on. Our car broke down yesterday; luckily the island repairman thinks he can still order the part from the mainland. What if we run out of vital prescription medication? How long are we hunkering down for? For the moment, the wild irises, the sea breeze, the nightingales, the bees in the rosemary bushes, the green breathing of the forest seem to outweigh these risks. ■

Simon Callow

March 19, 2020

LONDON, ENGLAND—Only literature can help us get a handle on the present pandemic—we have no personal experience to guide us. We vainly scan the pages of Camus, whose plague is metaphorical, and Defoe, in which it is an ingenious daily, hourly enemy. But this one is different, more like a transparent fog, leaving its traces everywhere and anywhere, to be accidentally picked up and passed on, until it finds its ideal destination in the elderly and ailing, whom it steadily, unerringly destroys. And short of sealing ourselves up in plastic bags and never setting foot outside our disinfected homes, we can do nothing about it.

One’s every instinct as an actor is to provide relief, to offer an alternative, to remind people of their common humanity, to get ’em laughing. But the direst aspect of this, our plague, is that we performing artists cannot contribute the greatest gift we have to offer, at exactly the moment when everybody needs us most. The theaters are closed, as are the studios and the concert halls and the museums. In Britain, the national ur-myth remains our stoical heroism during World War II, and self-delusory though much of that particular narrative may be, it is true that during the Blitz and throughout the war, the great pianist Myra Hess gave regular lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery. The actor Donald Wolfit and his company played the classics through the Battle of Britain, in 1944 Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson led the Old Vic company at the New Theatre as the flying bombs exploded all around it, while the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, featuring Margot Fonteyn and Robert Helpmann, toured the country regardless of the air raids on the great cities where they danced.

Even in living memory—in my memory, during my lifetime as an actor—throughout successive waves of IRA aggression, the theaters and the concert halls never closed, nor did the art galleries or the museums. Now they have, every last one of them. The evil, mocking cunning of this virus is to have rendered all those temples of delight and enlightenment potential death traps. We all of us—actors, musicians, poets, trick cyclists, prima ballerinas, curators, stage managers and master carpenters—feel grounded, cut off at the knee, hopeless and helpless to contribute. The whole point of the theater, since the Greeks, at any rate, has been to gather the citizens together, to remind us, as Shakespeare so incomparably put it, that “we are not all alone unhappy.” I’m afraid Mr. Johnson’s daily press conferences and Mr. Trump’s addresses to the nation can’t quite achieve that. Let’s hope that the time when the professionals can take over is not far off. ■

Mark Gevisser

March 19, 2020

CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA—By the time our housekeeper Daisy Nyathi (not her real name) walked into my home at 8:45 on Tuesday morning, she had been in close personal contact with a hundred people already. These included: the husband and toddler she shares her room with; the ten other people who are other tenants in her rent-by-the-room township house; the women and kids at her daughter’s creche; the dozen people who crowded around her in the long line for a minibus taxi to town and the thirty people jammed into the taxi; the same again on a second taxi ride to my suburb.

Shamefully, I first thought of the risks Daisy needed to take to get to work only the night before, when I stumbled upon a tweet. It was a photograph of the thousands of people crammed into Johannesburg’s Bree Street taxi rank, waiting for their rides home to Soweto or one of the other black townships. Of the scene, the tweeter drily observed: “a gathering more than 100 people.”

This was a reference to an announcement made the previous night by South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, when he declared a “national state of disaster” to combat the coronavirus epidemic. Among its terms was the prohibition of gatherings of more than one hundred people.

South Africa does not have an epidemic, yet. But today, there were one hundred and sixteen confirmed cases (though no deaths), up from sixty-one on Monday. There’s a notion that’s taken hold in the townships that Covid-19 is a “rich man’s disease.” This has created an odd inversion of the ideas about poverty and disease that pertained under apartheid, when the state used the canard of “slum clearance” to move black people out of the city and create the segregation that still makes it so difficult for someone like Daisy to get to work.

At the moment, the truth is that someone like Daisy is more likely to catch the virus from a jet-setting employer than from a fellow minibus taxi commuter. Most of the cases, to date, are people who have travelled abroad, but this is changing. And the consequences of this could be catastrophic—given a large population with immunity already compromised by HIV and tuberculosis, an already-strained health system, and the impossibility of social distancing in densely packed townships and rural villages. Nearly half of young South Africans do not have a job, and many live in impossibly crowded situations without running water or toilets.

And then there is my country’s singular history of othering. Last week, a local newspaper led with the headline “W[estern] Cape Covid-19 suspect,” identifying the province’s Patient Zero (albeit not by name). The word “suspect” would be suspect anywhere, but even more so here. In South Africa, for example, AIDS remains more stigmatized than in most other African countries: it began, under apartheid as both “the gay plague” and “Black Death” (the latter a racial epithet).

In China, social distancing is compulsory, but we South Africans are tjatjarig, an onomatopoeic word (CHA-cha-rikh) meaning “mouthy” and connoting disrespect for authority—not so surprising thanks to recent decades of official kleptocracy and inefficiency. For the first time since his 2018 election, though, Ramaphosa looked like a real leader when he made his somber address to the nation. South Africans —already facing energy and economic crises—heaved a sigh of relief that the people in charge were doing their jobs. But the nature of South African society is such that no one is going to be able to enforce the social distancing rules, unless we do it ourselves. And so we will need to exercise another vaunted South African value: ubuntu, “I am because you are.”

This unpredictable pandemic plays on both personal anxiety and civic responsibility, and is establishing new moral conundrums: If I flee the city, will I put the old folks back home at risk? When should we self-quarantine? In our household, we are watching the unfolding situation carefully, and doing our best to follow the rules.

Daisy will not come into work, but still get paid, until things are clearer. Tonight, my partner and I are working out the cleaning roster. ■

Sarah Manguso

March 19, 2020

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA—At the pharmacy, a young man wearing a gray hoodie, cargo shorts, flip-flops, and an expensive-looking, black air-purifying mask leans on the crowd-control barrier, rubs his bare hands listlessly back and forth across it, then wipes his eyes. Then he puts his hands back on the barrier. The mask muddles his voice, and the pharmacist can’t understand what he’s saying. My screenwriter friends would flag this scene for being a bit too on-the-nose.

The cashier calmly answers my complicated insurance questions. Despite the protestations I made to my insurance provider, I will run out of pills in twenty-seven days. Because I am immunocompromised, I am particularly troubled by the sinus infection I haven’t been able to clear for the past two weeks. In my jollier moments I imagine collecting wagers on what will take me first, my autoimmune disease or the virus.

When I ask the stocker where the thermometers are, he looks straight ahead, not at me, and barks, We’re out! A bit too on-the-nose, again. Everyone in the pharmacy is suddenly a stock character, myself included. It’s a movie everyone in the store is collectively making, but no one will want to watch.

I’ve been thinking about books written by those in hiding or relegated to confinement by the state. I would be creating a record of this time myself if I weren’t suddenly homeschooling a second-grader. He seems to have taken on the full weight of the historical moment and writes obsessively in his own pandemic journal. He doesn’t want to share what he’s writing. Already he conceals a complex emotional life.

Squirrels and stray cats run all over the streets, now that the cars and the children are gone. The crows are uncharacteristically quiet. My son and I see the same people and dogs every day. We keep our distance, across the street and down the block, but we always wave at each other, our shared acknowledgment the equivalent of a friendly touch. ■

Ruth Margalit

March 18, 2020

TEL AVIV, ISRAEL—On Monday, the second day of a countrywide closure in Israel, I took my children to the Tel Aviv beach, thinking: “There. Not so bad.” As I opened my laptop to write this, I was even a little smug, noticing the empty roads, the Yom Kippur–like stillness. Maybe it will teach us to slow down.

Then, moments ago, the Israeli Health Ministry released urgent new orders. Public parks are from now on forbidden. So are beaches and nature reserves—forget about museums or cafés, which have been closed for several days. Walks are to be limited to ten minutes at a time: one parent and one child only. There are to be no playdates. No congregations of more than ten people. No medical services except for emergencies. A world the size of our living room.

“Is there kindergarten today?” my son asked this morning, bleary-eyed, at 6:10. I told him there wasn’t. “Oh.” He thought for a moment. “We’re changing prime ministers today?” Call it the result of three election cycles in a year, tossed in with a global pandemic. What do you tell a boy who is beginning to grasp that his life is dictated by colossal failures outside of his control?

His sister, at eighteen months, has taken to scolding me (“nu, nu, nu!”) whenever I touch my face—which, I’ve come to realize, I do obscenely often. Where did she pick that up? What else is taking shape in their young consciousness? Will they forever resent washing their hands? Being in enclosed spaces? Will they be the “corona generation,” much as those who came of age during the Great Depression still stuff bills under the mattress?

News broadcasts here are filled with the schedules of people who have tested positive for the virus. It’s a surreal sight: doomsday anchors reading out the trivialities of a person’s day.

8:30 AM: ATM on Yehuda Maccabi Street. 9:50 AM: Shufersal (a popular supermarket chain) in Yahud. 12:30 PM: Zion falafel joint.

“Live your life as if each day will be plastered on social media,” a joke circulated on WhatsApp the other day. Other bleak jokes have been circulating, too. “On Saturday, weather permitting, we’ll tour in the footsteps of Patients 37 and 148.” “People are advised not to hug or kiss. Ashkenazim carry on as usual.” “If you feel feverish, lightheaded, sweaty—You’ve just realized you’re stuck home with the children.”

You get it.

The pandemic feels both futuristic and biblical, eschatological and utterly banal. Some friends are using the time to potty-train their kid or go through the entire Netflix documentary catalog. Another suggests that you “move through your home with mindfulness.” Tell that to my son who figured out that our bookshelves, once emptied, can make a great ladder for moving his sister.

I saw a picture from a NASA satellite the other day. It showed an aerial view of China, without its cauliflower of pollution. The skies were blue again. Now there’s something to look forward to. ■

Miguel-Anxo Murado

March 18, 2020

MADRID, SPAIN—We’re now on the fifth day of our confinement. This is a watershed: five days is the average for symptoms of coronavirus to appear after an infection. It’s not a guarantee, but it’s a reassurance in an almost superstitious way, one you can cling to. Since the Spanish government ordered the whole country to lock ourselves up in our homes for—in principle—two weeks, this has been in the back of many minds, and certainly mine: What if we are already infected?

The stern robotic voice on the radio announcement constantly repeats that, in that case, we shouldn’t go to a hospital. Hospitals are at breaking point. Many doctors and nurses are infected. There are not enough intensive care units, not enough beds, not enough face masks even. Every evening, at eight o’clock, everybody—the whole country—reaches for the windows to give a resounding ovation to the healthcare workers. We want to cheer them up and show them we know they’re risking their lives for us.

But in the hospital, doctors have to decide which patients get to intensive care and which are left to die. It is as simple as that, there’s no way to gloss it over. If you fall ill at home, you have to call a phone number and, you hope, they will come and test you, and then monitor you from the hospital. But testing kits are running out, and the phone, they say, is overwhelmed and busy at all times. So we know we can’t expect much help.

Not far from here, at least twenty old people have died in just one nursing home before anyone could give them any assistance. Yesterday, across Spain, almost two hundred people died. Today, at least another hundred will do so. We are to expect worse in the days to come.

Our family is three at home: my wife, my four-year-old Martín, and me. We have enough food to go for two weeks. We’re okay. We’re lucky, since my wife and I can both work from home. Entertaining a kid for so many hours a day is tougher than I thought, but it’s nothing compared with the hardships I imagine all around us, perhaps in this same block of flats.

I’ve been a war reporter, so I’m no stranger to curfews or dangers. But I had never experienced anything like this: a simultaneous curfew of a whole country—perhaps, soon the whole planet—and a danger that is minute and invisible. In war, fear is noisy. Here, it takes the shape of an eerie silence.

I’m concerned, not scared, and yet I’m being pedantically strict with my precautions for fear of being guilty of causing someone else’s infection. Epidemics are also special in this: they threaten not only your life but your conscience, too. That’s why I venture outside only to throw out the garbage.

Yesterday, on my way out, I stumbled upon a neighbor, a girl I don’t know. We both stopped at a distance to figure out how to pass each other while keeping the recommended six-foot distance, but we did it so clumsily that we actually touched one another. Would that be the contact to do it? Nonsense, I told myself later in bed, trying to sleep. I touched my wife’s body under the blanket and it felt warm. Too warm? Then I fell asleep. ■

Tim Parks

March 18, 2020

MILAN, ITALY—March 8. We started with the best intentions. We had gotten over the irritation of seeing all the things that enrich life in Milan closed down. The restaurants, concert halls, theaters, cafés. My gym. Her yoga. We rather appreciated a new feeling of community on the streets, here on the edge of town. A new awareness, in particular among the various ethnic groups. It boded well. We knew that the special problem with this illness is that some 5 to 10 percent of those with symptoms will need an extended stay in intensive care, and that places are scarce. It was our duty not to fall ill and be a burden.

We hunkered down.

After all, how different was this from our normal day? Sitting home writing, translating.

We smiled when the media told us about people singing on balconies. There was no singing around us.

It did seem a little excessive to be asked to download and print a form to fill in and sign every time we went out of the house to do some shopping. Couldn’t they trust us to be responsible? But so be it.

More understandable was being asked to line up outside the supermarket, yards apart, so that only ten would enter at once. The man behind us shifted his mask occasionally to take a drag on his cigarette. My partner whiled away the time checking smoking-related fatalities in Italy: 80,000 a year.

We have been unable to find masks. Anywhere.

We decided to take advantage of the extra time at home to play the piano, to read, to watch movies. Ten days on, it hasn’t happened. We had reckoned without the pull of the media. The relentless narrative of rising levels of contagion, the daily body count, stories of coffins stacked in churches, dwindling places in intensive care. This reinforced, as it was no doubt intended to, our resolve to stay indoors.

The pleasant new community spirit that so impressed me in the early days began to morph into a more energetic patriotism. Public radio played the national anthem and invited us to open our windows and sing. Italy is a model for the world to follow, our prime minister says. Much talk of being at war.

Meantime, I study the figures from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità. As of March 13, 1,266 deaths. (633,000 people die each year in Italy, an average of around 1,700 a day.) March 17, 2503. Average age of death: eighty-plus. “Two victims without serious preexisting pathologies.” Most with two or three.

“But do you want to be the one who’s ill when they run out of beds,” my partner asked. “After all, you’re sixty-five.” She is from Taranto, in the far south of Italy, home of ILVA, Europe’s biggest steelworks—notorious for its unacceptable levels of pollution. She showed me a study calculating that in an eight-year period this had led to just short of 12,000 deaths. But ILVA is too important to close.

Until coronavirus came along. On March 16, they decided to close down half of it, reducing personnel from 8,000 to 3,800.

There are seventeen cases of coronavirus in the entire province of Taranto.

I contemplate another day indoors, filling out forms to line up outside the supermarket. The weather is beautiful in this country I love where I’m presently writing a book in honor of Garibaldi and the Risorgimento movement. But yesterday, the newspaper La Repubblica tells me, the police charged almost 8,000 people for being “away from their homes without good reason.” In forty years here, I’ve never seen the like. The economy is shot. The social repercussions will be enormous.

I’m not sure all this adds up. ■

Eduardo Halfon

March 17, 2020

PARIS, FRANCE—Today was the first day of the lockdown in Paris, or as the French call it, le confinement. From my window, as I write this, I can see a completely empty rue de Fleurus (where almost a century ago, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas received so many artists and writers). There are no pedestrians. All shop windows are dark, all restaurants and cafés now closed, their tables and chairs neatly stacked inside.

From today on, and until further notice, anyone outside must carry with them an official document called Attestation de Déplacement Dérogatoire, duly filled out and signed, asserting the explicit reason for any excursion. Only five possibilities: movement between home and place of work; movement to buy things of première nécessité (such as food) in authorized establishments; movement due to medical reason; movement due to a pressing family situation, assistance to vulnerable persons, or childcare; and movement linked to limited individual physical activity, and the needs of pets.

One must not, we were warned, go outside for any other reason, nor leave the house without this document. In other words, a safe conduct, as in a war zone.

The lockdown was to start at noon, and so, with a few minutes to spare, I decided to hurry out to the boulangerie across the street, one last time.

The glass door was now kept open. There were big blue crosses on the floor—made with duct tape—leading up to the counter. I walked in and stepped on my blue cross and thought that the bakery itself was a kind of theater stage, and we clients, well-distanced from each other, were the actors hitting our marks. I slowly made my way up to the counter, in front of which they’d placed a long series of tables, to keep the gloved and masked employees at a safe distance from us.

I ordered a baguette and a pain au chocolat for my son and said to the lady that I’d miss coming there every morning for the duration of the lockdown. She scoffed loudly and said that of course they would remain open throughout, and at regular hours. More than baffled, she seemed insulted. And so I apologized and just handed her some coins.

As I was walking out, taking care not to accidentally touch anybody still standing on their blue cross, I realized that all else in Paris could fail, all else could collapse and close, all pharmacies could run out of hand-sanitizers and masks and even medicines—but there would always be a baker making bread at four in the morning, and there would still be Parisians walking around with a fresh baguette tucked under their arm, the end chewed off, a safe conduct in their pocket. ■

Anastasia Edel

March 17, 2020

OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA—By Thursday afternoon, downtown San Francisco, already void of tourists, had turned ghostlier still. On street corners, people who, less than a month ago, had been lining up to spot Keanu Reeves shooting his new Matrix movie were now loading computer towers and monitors into their Uber and Lyft rides; they’d been told to work remotely.

From behind the glass door of a shuttered Illy café on Battery Street, the Italian manager waved at me, his hand in a blue disposable glove, with an apologetic smile. For days, his parents, quarantined in Florence over the coronavirus epidemic, had been imploring him to stay away from people. It seemed as if they got their wish granted.

Boarding a bus east in the eerily empty Salesforce Transbay Terminal, a couple of hand-sanitizers as a parting gift from my colleagues at the bank where I work—or worked?—as a contract writer, I took the first row of seats, to the right of the driver. I didn’t know when I’d be riding home from work again, and I wanted to get an unobstructed view of San Francisco Bay, obliviously magnificent on this spring day.

The bridge traffic was light. It took us less than ten minutes to get down to the lower span, from where I could see the white cruise ship docked at an Oakland pier, a lonely helicopter hovering above it. “Princess death,” the driver muttered as we pulled off the bridge and began weaving our way toward the Oakland maze. My neighbor’s parents had been on that ship; they were now at Travis military base, awaiting the results of their testing.

I spent the weekend oscillating between “this can’t be real” and asking myself myriad odd questions, such as whether to explain to the kids, at least to the sixteen-year-old one, how to claim our life insurance. I raided the rapidly depleting grocery aisles, picking up things I never thought I’d need, like pinto beans or soap in a twelve pack, all the while feeling the futility of the effort. If growing up in the shortage-ridden Soviet economy taught me anything, it’s that you can’t outsmart malfunctioning lines of supply and demand: you never knew what would disappear next, and even with things you guessed right, you’d eke out your supply as you might, but eventually run out.

The one thing that’s worth stockpiling is decency, that silver lining of our lives back in the USSR, with its near-permanent state of national emergency. Today, in America, where decency has taken a beating over the past four years, it might mean something as straightforward as not buying both of the last two loaves of bread, not forwarding that doomsday chain email, and not going out even if you are healthy.

Tomorrow, our challenges might not be so simple. Since I started writing this, a shelter-in-place order for six Bay Area counties, including mine, has been issued. Decency won’t save us, but it will make our altered lives more tolerable, come what may. ■