This running series of brief dispatches by New York Review writers will document the coronavirus outbreak with regular updates from around the world.

—The Editors

Sylvia Poggioli in Rome 🔊 • Jenny Uglow in Cumbria • Minae Mizumura in Tokyo 🔊 • Hari Kunzru in Brooklyn 🔊 • Rachael Bedard in Brooklyn • Lucy Jakub in Northampton 🔊 • Alma Guillermoprieto in Bogotá 🔊 • Nick Laird in Kerhonkson • Caitlin L. Chandler in Berlin • Yiyun Li in Princeton • Lucy McKeon in Brooklyn • Dominique Eddé in Beirut • Zoë Schlanger in Brooklyn • Ursula Lindsey in Amman • Nilanjana Roy in New Delhi • George Weld in Brooklyn • Richard Ford in East Boothbay • Eula Biss in Evanston • Martin Filler in Southampton • Ben Mauk in Penang • Michael S. Roth in Middletown 🔊 • Sue Halpern in Ripton • Ivan Sršen in Zagreb • Tom Bachtell in Chicago • Adam Foulds in Toronto 🔊 • E. Tammy Kim in Brooklyn • Keija Parssinen in Granville • Yasmine El Rashidi in Cairo • Merve Emre in Oxford • Tolu Ogunlesi in Lagos • Verlyn Klinkenborg in East Chatham • Rahmane Idrissa in Niamey • Aida Alami in Paris • Raquel Salas Rivera in San Juan • Michael Greenberg in Brooklyn

Previous journal entries: Madeleine Schwartz in Brooklyn 🔊 • Anne Enright in Dublin 🔊 • Joshua Hunt in Busan 🔊 • Anna Badkhen in Lalibela • Lauren Groff in Gainesville 🔊 • Christopher Robbins in New York • Elisa Gabbert in Denver 🔊 • Ian Jack in London • Vanessa Barbara in São Paolo • Rachel Pearson in San Antonio • A.E. Stallings in Athens • Simon Callow in London 🔊 • Mark Gevisser in Cape Town 🔊 • Sarah Manguso in Los Angeles • Ruth Margalit in Tel Aviv 🔊 • Miguel-Anxo Murado in Madrid 🔊 • Tim Parks in Milan • Eduardo Halfon in Paris 🔊 • Anastasia Edel in Oakland 🔊

Michael Greenberg

March 29, 2020

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK—A roving, low-wattage panic prevails on the streets of central Brooklyn. There are the scrupulous citizens who solemnly keep their distance, the flouters who dance with death like the calaveras of Mexico, and those who live in perpetual crisis and don’t believe that the virus has presented them with more to lose.

At my local liquor store, the bulletproof glass, behind which an elderly Taiwanese couple toils, is now more of a germ barrier than a protection against robbery. The perennial loiterers thoughtfully try to suppress their perennial coughs, as I join them on line to await our bottles of potable disinfectant, theirs a mini shooter, mine a relatively luxurious quart of whiskey. It’s spring, the sun is warm for a few hours, and they laugh and roar and slap each other’s hands. The civic duty of social distancing is a hard sell to this crowd.

I exchange greetings with one of the regulars. During normal times, he might be found hanging around the hardware store down the street, offering his services to old or handicapped customers with mildly clogged drains or chirping smoke detectors they’re unable to reach. When I lost my keys last summer, he voluntarily searched the streets with me for half an hour till we found them. To celebrate, we bought an instant lotto ticket and won twenty dollars. A joyous hour. Now I wonder if, with his running bloodshot eyes and general self-disregard, he would survive a bout with coronavirus.

Never mind the super-rich or even the less spectacularly well-off. This pandemic makes sharpest the divide between those who have a little and those who have nothing. The chasm separating the person with, say, $7,000 in the bank or a family member or partner financially secure enough to offer a sustaining infusion of money from the person with no savings who rents a room or even just sleeping rights to a couch or stretch of floor somewhere in the closest of quarters, with no hustle to ply now, no job to go to, is scarily wide. Help from unemployment insurance and the stimulus package that Congress has just passed will not reach thousands of members of New York’s vast “informal economy,” as economists call it: cash-only nannies, house cleaners, home health aides, pickup musicians, kitchen workers, artisans, and day laborers who exist under the radar of acceptable documentation.

A psychiatric nurse I know in Canarsie worries about the undocumented immigrants from her home country of Jamaica who bunk, for a small fee, in her house and garage. On one of my walks, I run into a young friend who lives with four siblings, two parents, and various extended family members in a modest-sized apartment. We compare our situations: I am wandering out of loneliness, he out of a need to be alone. He is almost in tears as he frets about the increased probability, in his current confinement, of normal domestic quarrels turning into violent crimes.

There are small changes, too. Wrinkled latex gloves have taken the place of used condoms on the littered sidewalks. The avid ganja smokers who hang out on the stoop a few doors from where I live have taken to wearing matching bandanas around their faces like bandits, in lieu of surgical masks. They lift the bandanas to toke on a blunt that is passed around from one mouth to the next.

Advertisement

Self-preservation is most people’s instinctive response to a pandemic. The obviously sick become like lepers, mortal threats, criminals in a way, because they have been struck with the curse the rest of us dread. “Stay away from our door!” we say, as if with the blood of a slaughtered Passover lamb. On the other side of this fear is the bracingly humanitarian fact that our entire city (and large swaths of the world) has banded together, in isolation, to protect its most physically weak citizens, even though the health risk to the majority is minimal. We live with these contradictions naturally and without shame.

And yet, it’s riveting to behold the world veering from a consumerist to a monastical existence. On Friday evening, we stood outside with our neighbors and, in a planned citywide tribute, cheered New York’s health workers endangering themselves to keep the fabric of something precious from tearing apart. At night, indoors, we gaze across at our neighbors from afar. Everyone is home, every window lit up, side by side, each of us emitting our worried beacon in solitude. ■

Raquel Salas Rivera

March 29, 2020

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO—Since Hurricane María, our closets have changed. Many Puerto Ricans have moved our funeral clothes to the most accessible racks. Still, when I need new clothing, I keep buying prints that have the brightest colors, flowers, palm leaves, and anything that makes me feel intensely alive.

This month, three people close to my chosen family have died, none from complications related to Covid-19. They were already fighting sickness and grief. Two died during the pandemic, and being confined inside during curfew has made arrangements all the more painful. How does one say goodbye without ceremony or any communal gesture? As things get worse, we will have to find new ways to grieve.

Puerto Ricans work out how best to protect each other despite contradictory messages. The governor has extended the curfew. The government has also established new curfew rules, which feel as arbitrary as the old ones we faced after María. Back then, we weren’t allowed to drink (there was no explanation from the government). Now, we can only leave the house by car to go to buy food or medical appointments if we follow a numerical rubric: license plates with even numbers can use the roads on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and those with odd numbers can travel on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday.

Many people have noted that zero is both an odd and even number. This observation suggests that some people can break an absurd rule that claims to protect us, but being in the zero space of colonialism also means we are doubly punished: every time a zero leaves to go to the supermarket or pharmacy, they are at the mercy of an individual police officer’s interpretation of that mathematical distinction. My mother says, “El cero, sálvese quien pueda.” (Zero is at the mercy of God.)

On the other hand, much tourism has continued uninterrupted, despite government efforts. The police finally began asking tourists to leave the beaches. One newscaster asked a couple biking in Condado, a tourist area of San Juan, if they knew there was a curfew. They answered, “But your island is so beautiful!”

Because I live with my partner, Sofia Gallisá Muriente, in Old San Juan, we are both exposed to tourists, who always seem lost, wandering the old Spanish colonial streets seeking taxis or open restaurants, which they fail to find. One day, wearing gloves and a mask, I withdrew money from an ATM as my mother waited in the car. When I returned, a woman was standing between me and the door. She was confused, thinking my mother was a taxi driver offering her services. I waited until the tourist moved far enough away that I could get in the passenger seat.

Nearby, a few cruise ships remained docked at the port. Their silent girths weigh on us as a reminder that we have already been exposed to the virus in unknown numbers. Vacationers no longer seem simply intrusive; they now feel deadly.

Like many in my position, living on the north side of the island, I’m experiencing anew the familiar survivor’s guilt that followed María. There are thousands of people in Puerto Rico’s southern half who are still living under tarps because they lost their homes after the earthquake swarm hit the island in January. How can they be expected to #quédateencasa or #stayathome when they still lack homes? Sofia tried to describe what we are feeling:

Advertisement

After María, there was this feeling: you would sit at home wondering how people were doing in Jayuya, Adjuntas, Ponce, and everywhere else on the island. You also tried to imagine places you loved changed by the storm. It became a kind of exercise to imagine the disaster’s effects. Now it’s similar, except now it’s the whole world. ■

Aida Alami

March 29, 2020

PARIS, FRANCE—A few days ago, we all became soldiers. French President Emmanuel Macron said in a televised speech that we were at war. At war against a virus that spread exponentially, causing an unprecedented public health crisis across the globe and shutting down one country after the other. So that’s how it went. We collectively accepted the order of the day to stay at home, to buy food, avoid contact even with loved ones, and surrender our freedoms in the name of an overriding civic duty to vanquish the monster.

Only, Macron isn’t my president and France isn’t my home.

Over two weeks ago, before the crisis rapidly escalated, I was in Paris on a short trip. I knew, we all did, that we were days away from a shutdown similar to Italy’s. As my attention was on Europe, I failed to see the signs back at home in Morocco. On Friday March 13, rumors started floating around the Moroccan media that flights to the North African kingdom from Europe were going to get cancelled. I quickly booked a flight back home, but on that same day, Morocco banned flights coming from and going to France. For the next three days, every time I tried to book through a new route (via Lisbon, Dublin even), my flight got cancelled. After the third time, and hundreds of dollars wasted, I had no other choice but to stay in Paris.

“Let the confinement begin,” I wrote in a WhatsApp group to my Columbia friends from graduate school: a chat group made of journalists confined in several parts of the world like Italy, Jordan, the United Kingdom, Mexico, Australia, and Colombia. We were all getting hit by the same reality, one after another, actively keeping each other informed on what measures were being taken in our countries, and also, trying to get some mental relief from the onslaught of negative news by sharing funny memes and not-so-funny videos of people fighting over toilet paper.

A couple of days after starting to settle in an apartment that wasn’t mine, in a city where I no longer lived, I woke up to a message from my brother that said, “look at Dad’s Twitter.” There it was, a selfie taken in a café in the center of Marrakesh: he was out of the house—despite several messages from me and my siblings begging our parents to stay home for the weeks to come. I got angry at my parents again, and I told my mother that if something happened to them, none of their three children would be able to get to Morocco (my brother lives in Cameroon, my sister in Paris).

Our parents’ nonchalance seemed to capture the general state of fighting the virus in Morocco: keeping people indoors would be a huge challenge in a country where people tend to trust fate more than anything to take care of them.

As I remotely observed the events unfolding at home, a mixed picture started to emerge. Videos of deserted streets and closed shops, sending the message that people understood the gravity of the situation, were contradicted by videos of police officers violently cracking down on those who didn’t follow the rules and who refused to stay home. Friends who once fervently fought for the rule of law and human rights were suddenly sharing videos of cops calling them “Moroccan heroes.”

In spite of this cognitive whiplash, I am amazed myself at the volunteers who are going around the country telling people to stay home and explaining the danger of the virus. I am thankful that the Moroccan government decided to react quickly, but I worry nevertheless.

The number of cases of people infected is officially still not high, but years of neglect of the health-care system means that the country does not have the means to deal with a crisis of this scale. But that’s not all. While these emergency measures are necessary, this moment also carries the painful risk of empowering authoritarian governments. Moroccans have suffered for years from a lack of access to public services and also lack of freedoms. Though I have no idea when I will be able to return home, I have never felt closer to it. ■

Rahmane Idrissa

March 29, 2020

NIAMEY, NIGER—Late March is unusually balmy. By this time of the year, the fiery Sahel heat should have long been upon us. The other day, there was a rainy-season downpour, with thunderclaps and large puddles in the aftermath, as if it were a day in August. This adds to the sense of oddity and things being out of whack now transpiring in the syllables “corona,” unknown here just yesterday (the beer brand isn’t popular in Niger, which is Castel and Flag country). I left the Netherlands at the end of February. The day before I took the plane for Niger, I joked with my favorite French fries seller in Leiden that “eventually, we’ll all get it,” but I did not imagine one minute that in only ten days “it” would get me stuck and stranded in—fortunately—my own country.

It seemed to come by stages. After a week working in Niger, I flew to Burkina Faso, a country next door, to meet a documentary filmmaker. That’s where I heard a boy announce to all present the momentous news he’d just heard, “Corona is in Ouaga” (“Ouaga” is shorthand for Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina). It was brought back by a local pastor who had been in a megachurch gathering at Mulhouse, in Alsace, one of the starting-points of the epidemic in what has turned into France’s coronavirus hot spot, the “Grand Est.” After the news broke, a physician was interviewed on television about the potential impact in Burkina. He said, with the reassuring tone of a family doctor, that Burkina lacks the resources to cope, many will die, and what could be done would be done.

Niger was then still “corona-free.” The day I returned to Niamey, Niger’s capital, there was a tense citizen demonstration against a huge war-profiteering and cover-up scandal involving the top brass of the ruling party. Three people died in the repression. The Corona Effect was immediately visible in the fact that the international media—especially Radio France Internationale, an influential outlet in French-speaking countries—barely registered the event.

When the president made a speech forbidding all gatherings of more than fifty persons, the main reaction in the public opinion was that he was battling the citizens’ anger, not a virus. And when a first case was announced, people were skeptical because someone had the idea of a viral social media prank, broadcasting on WhatsApp a message in which he claimed to be the so-called “corona-patient,” that he was healthy and that his “case” was all a government plot.

Eventually, the sense of menace sunk in, but in slow motion. Cases are coming in a trickle. No one I know has got it and I know no one who personally knows anyone who’s got it. Yet the continuous flood of startling information from abroad has persuaded general opinion that this is real, like the stench of something odious that’s on its way.

So, what to do with the mosques and markets? Many can’t see why they should not pray shoulder to shoulder in the mosque, as Islam prescribes, apart from the fact that the police may raid. For some, praying the right way has become a black-market affair. Information is whispered that in such or such place, people are still doing it, so let’s go there.

Markets are to close early everyday so that they can be washed. In a village market, not far from Niamey, some young men arrived yelling “the soldiers were coming” to shut down the place. This was much before closing time, but terrified buyers and sellers—military and police can be a brutal lot in Niger—frantically ran around to pick their stuff and leave. In the chaos, the young ruffians pilfered freely and made away with a small fortune.

The day before writing this, new measures were announced. Niamey was “closed” and subject to a night curfew. Instead of confining the people within the city, the city itself was confined. The president explained that this was because it was the only place in Niger touched by the epidemic, and that, in the seventh century, the Caliph Umar had once cancelled a trip to Syria when he heard that it was hit by the plague. I wondered how one could close a city that has no walls. ■

Verlyn Klinkenborg

March 29, 2020

EAST CHATHAM, NEW YORK—The other night, I realized that the sentence-maker in my head was working again. It had been out of whack for a few weeks. Suddenly, about three in the morning, an old-fashioned planetarium projector seemed to rise out of a trap-door in the base of my skull and began casting words and phrases onto the dark inner dome of my mind, as if they were stars and constellations. I tried out a couple of sentences, simple ones like, “I heard the spring peepers singing tonight,” and “I hope a merganser lands on the pond soon.” They led to other sentences, which carried me, one by one, far away from where my body lay, ready to sleep again.

I’ve spent a lot of time recently urging the young writers I’ve worked with to be patient if they find themselves unable to write. A certain kind of cognition seems to have slipped away temporarily. My brother says he finds it hard to play chess, though I watched him doing so with his son—both of them lost in meditation—only two weeks ago. The kind of cognition I mean involves holding an idea in mind while picturing its consequences as they unfold in a short-term imaginary future. Writing can sometimes feel a little like chess that way. But mentally chasing sentences in the darkness of early morning isn’t like that at all, though it is a kind of writing. The sentences move haphazardly, often without rule or connection, and that kind of movement feels surprisingly reassuring, if only as an alternative to the feverishly connected kind of thinking that should really be called worrying.

There’s something else I say to the young people I talk to. I tell them about my parents. My dad was born in November 1926, my mom in January 1928. In other words, their young lives occurred almost entirely during the major international crises of the Depression and World War II. They’re both gone now—my mother died in 1971, my dad in 2008—but I know they hoped their children would never experience the kind of cataclysms they were forced to take for granted. I try to think about the differences between their worlds and mine, and I conclude that it’s almost easier to count the similarities, because there are fewer of them.

I keep returning, of course, to the most demoralizing difference of all. During most of those terrible years from 1929 to 1945, this country was being led by a person—Franklin Delano Roosevelt—who understood the extraordinary value of the public good—and the public means of ensuring it—and who knew how to communicate clearly with a nation that was listening for encouragement and reassurance. Thanks to polio—which struck him in 1921 and was one of the great medical specters of the twentieth century—he also knew a great deal about sacrifice. Not, perhaps, as much as a poor farming family like my mother’s, but enough to imbue him, despite his privileged upbringing, with an almost instinctive empathy for ordinary people living ordinary lives.

I remember as a child the fear that polio still caused among adults, even as an effective vaccine was being administered across the country. The vaccine was a triumph of science, medicine, and public policy, and it made it even likelier that I would live a life of the kind my parents might have hoped for their children. When I talk about these things, I never have to draw a moral. The young writers I know understand it intuitively. They realize, as so many people do, how much worse this pandemic has been made, in fact and in their own minds, by our sickening, if still unsickened, president.

It’s not the news about Covid-19 that frays my thoughts at night. It’s the condition of the public good in this country—the recognition that things have been turned upside down, that what matters most now, above all, is the private good. I have to ration my anger, not because there’s a limited supply of it but because it’s so damaging to my mental state. So I try out a sentence here and there in hopes that others will follow. “Today, three geese and a pair of mallards were floating on the pond.” “A red-winged blackbird made its buzzing, clicking call from the top of an ash tree.” “The red stalks of peonies are pushing upward.” ■

Tolu Ogunlesi

March 28, 2020

LAGOS, NIGERIA—Because of my work in digital communications (social media, less fancifully) for the federal government, I have in the last four years divided my time between Lagos, which I consider home, and Abuja, the federal capital. It’s now clear, however, that I will spend the next few weeks in Lagos—my longest stretch here in years—obeying the #StayAtHome message that now seems to encapsulate the fastest and surest way to defeat this stubborn virus.

That message has been the eureka! for me in Lagos in the last couple of days. It’s where all the public information energy should go, for a viral disease for which there is really no treatment, only the management of symptoms. As a poster I came across online put it: “For the first time in history you can save humanity by sitting at home and doing nothing!”

Sitting at home doing nothing means I have all the time in the world to imagine phantom symptoms of the coronavirus infection—and then I realize, to my great relief, that I’m not alone; social media appears to be full of people stuck at home assuming the worst.

I drove out to buy grilled fish on Friday night. A typical Friday night finds Admiralty Way on Lagos’s Lekki Peninsula jammed with cars, parked and moving. This night was very different. It felt like the evening of an election day, when the mandatory curfew has finally ended, but not the inertia it brought along. The typically crowded restaurant was empty; the colored lights were on display, but there was no music: takeouts and deliveries only. A swanky new restaurant directly opposite had only its drive-through section open. Down the road, the tables in the KFC were missing their chairs. The message was clear: no sitting, no congregating.

But there is no restriction of movement in this mega-city just yet; simply an admonition to stay at home as much as possible. That’s different from the city of Kaduna, five hundred miles the north, where there’s a twenty-four-hour curfew “until further notice.”

As of Saturday, Nigeria had only ninety-seven confirmed Covid-19 infections. Most of our cases have been from Nigerians returning home from abroad. Accordingly, the testing is reserved mainly for those who meet certain conditions—that is, people who have recently returned from a high-risk country, and are showing symptoms; or have had contact with a confirmed case, and are showing symptoms.

Today, though, one high-profile Nigerian musician tweeted about getting himself, his fiancée, and thirty “close associates” tested, despite none of them showing symptoms (though the fiancée came back positive, sadly). Most of the responses have been kind and supportive, but there are also those asking questions similar to those I saw on British Twitter as news emerged that Prince Charles was able to get the sort of expedited testing denied to multitudes of National Health Service workers who need it. How melancholy that it is taking the coronavirus to show us the world is actually a single country?

A century ago, the Spanish Flu came to Lagos, arriving by ship. At first, the city authorities were able to isolate all infected persons aboard these ships, but before long, they lost control. As the infections spread across the city, claiming lives on a huge scale, panicked Lagosians began to flee to the hinterlands, taking the disease along with them, to places even less prepared to deal with it. By the time the 1918 pandemic was done with Nigeria, more than 2 percent of the population lay dead.

To avoid a repeat, we must learn from the distant past and resist the urge to move. Stuck at home, however, most of us are not really coping well—even if we’re far less likely than Americans or Canadians, it seems, to defy “Stay Home” orders. As a Nigerian-American friend of mine living in the US told me recently, “You know, you can’t tell Americans what to do.” From Canada, another friend, Canadian-Nigerian, messaged me: “When you have people who have grown up [being told] about the inalienable rights of man, how do you tell such people to stay home if infected?”

Who knew a limitless sense of freedom could have any downside? ■

Merve Emre

March 28, 2020

OXFORD, ENGLAND—Living as Americans in England these past two years has prepared us for isolation better than anything else could have. We live in a cottage in the wall of a medieval fortress. My office at Oxford, where I teach, is off a staircase no one seems to climb. The days I would talk to another human being, other than my husband or children, in person were already rare. “Things are different in the north,” said my friend Paula, the only person we spent time with in any regular way before she moved away. We soon resigned ourselves to the fact that we would see no one, and no one would ask to see us.

Our weekday routine in isolation is no different from our typical Saturday. From 9 AM to 1 PM, I go to my office, which is a thirty-second walk through the college grounds, to read and write; from 1 PM to 5 PM, my husband goes to my office to work, while I take care of our boys. They are two and four, both curious, roguish, and inventive, dedicated playmates to each other and to me. With the college now nearly empty, they roam the grounds on treasure hunts, following maps my husband and I draw with them every morning—a new ritual to perform now that we no longer need to pack their bags for school. We stop by the lake and watch its two swans work to build this year’s nest, the male testing the reeds for slack before snapping off weaker ones, the female patting them into place, performing a short, inelegant dance to reposition herself. Last year, the pair had six gray cygnets, and only one was mauled by a fox—a death rate of 16.67 percent, which I fail to stop myself from calculating. My boys snap their own reeds and do battle with trees.

For a long time, our homesickness made us turn on each other; then, we began to turn on others. My husband and I had always joked that England would be a wonderful country without the English. In the first week of our isolation, my husband noted an increase in our quality of life. Since everyone is working from home, I no longer see my colleagues, and since I no longer see my colleagues, I no longer walk into rooms where people fail to look up, to say hello in return, to say they are well, thank you, and how you are doing; sometimes, it seems, as a matter of principle. Since the boys left school, I no longer ride the bus to drop them off in the mornings, and since I no longer ride the bus, I am no longer assailed by pale, choleric, ardently trembling women of indeterminate age, some in pleated slacks, some in leather pants, for jumping a queue that I simply cannot believe exists.

I once asked one such woman what confronting perfect strangers over trivial things did for her. She looked taken aback, as did everyone else who was just then pretending not to listen to us. “It’s about civilization,” she replied. “We are a civilized people.” This was two days before the electorate voted overwhelmingly for a Conservative Party that had spent the last decade reducing public health funding, leaving hospitals and caregivers terribly exposed during a crisis. It was four months before the Conservative government, in its initial, misguided attempt at managing the pandemic, announced that they would build “herd immunity” by putting hundreds of thousands of lives at risk; the lives of people already vulnerable and already isolated by age, illness, and poverty.

That night, I walked the empty aisles of the supermarket—no pasta, no beans, no peanut butter, no paracetamol. I came home and watched a video of an NHS nurse who had worked for forty-eight hours straight crying in her car because she couldn’t find fresh fruit or vegetables after her shift ended. Even so, I knew it was even worse back home, in the United States, under the staggering incompetence and utilitarian cruelty of a leadership that had long denied people health insurance, a universal income, sick pay. Far worse than our initial feeling of homesickness has been feeling that home was not now a place to which we wanted to return.

Initially, once keeping your distance became a government order, once everyone seemed to feel isolated and unhappy, my husband and I felt less isolated and unhappy by comparison; less alone in our loneliness. The self-pity we had nursed since being here was largely converted into an aura of smugness, a sense of mutual congratulation that the two of us had figured out how to make do with only each other back when no one else had to. This was, of course, a defense mechanism, secured with much false bravado and nervous laughter. We tried to convince ourselves that life before and life after we went into isolation were the same; that living far away from the people we love was no different from anticipating that the people we love—my mother is a pulmonologist, my father is a surgeon, my middle sister is the chief resident in an intensive care unit, my husband’s sister is a nurse—would be exposed and might fall ill or die out of our reach. Pretending we had already perfected self-sufficiency worked—until it didn’t.

Today, I watch my children fight the trees, and I think about my old isolation; how clear its presence is now and what its sudden absence makes visible, the good here and the bad back there. I realize that antagonism is a form of relation; maybe, for a critic, an especially energizing kind of social entanglement. It brings home not only who you can rail against, but, more important, what you want to change. There are days when I miss those silent men, those pale, choleric women who scolded me. “Bitch,” I think to no one at all. “Come back. Fight me.” I hope—for their sake, and for all of ours—that they stay at home. I hope that when it is finally safe to come out, we can all be better at figuring out how to care for one another. ■

Yasmine El Rashidi

March 28, 2020

CAIRO, EGYPT—Revolution is my immediate reference point. Shops shuttered, businesses closed, desolate streets under 7 PM to 6 AM curfew. Sirens blare insistently in the hours before and after lockdown, those of police cars patrolling streets. As elsewhere, or everywhere, there is no sense of when normality might resume.

The numbers of Covid-19 cases in Egypt are still low—by official figures (as of Friday), five hundred and thirty-six confirmed cases and thirty deaths. But we all know that numbers here are deceptive. Most Egyptians with symptoms are likely going untested. Capacity is limited, and few can afford the implications of what a positive test might mean. Egypt’s economic divide dictates in part how the coronavirus is addressed. The privileged are social-distancing, staying home, stocking up, taking walks in near-desolate residential neighborhoods. My mother has not left her house in some ten days, which itself has been disinfected. Those friends and relatives who can have retreated to beach houses on the Red Sea coast.

People I know have given their salaried house-helps paid leave, but the majority of the country’s blue-collar workers can’t afford time off. At my apartment, which has been under renovation, construction workers insist on coming in, even with the offer to suspend work with daily wages paid two weeks ahead. The calculus for them is straightforward: if they don’t work this week, they will have to work next. “In the end, work leads to more work,” my painter tells me. Plus tips, he notes, “add up.”

This informal Egyptian economy makes up earned income for more than 50 percent of the population, and its line of separation is felt when simply crossing from one part of town to another. In the residential enclave of Zamalek, where I live, the days are quiet and the streets mostly still. I walk my dog with the sense that the city is my own, that everyone is being cautious. But over the bridge on the other side of the Nile, and as I turn onto Ramsis Street in downtown Cairo, pedestrian traffic is many times higher. Mechanics’ workshops are still open, people crowd around small stalls selling wholesale housewares and produce, and the main train station that connects the entire country is teeming. Standing there, I feel suddenly conscious of my facemask and gloves, when only one in every fifty or so people there are wearing them.

The only thing that unites this country of almost 100 million is the curfew, imposed on us with the threat of heavy fines. As I take hours-long walks around the city, I stop at pharmacies and find that rubbing alcohol is now hard to come by. Yet I see litter in the form of hospital masks and plastic gloves everywhere—these seem still available in abundance. As I’ve been following the international news—most closely of New York, where loved ones live—I take this garbage of ours to mean that our turn has not yet come. ■

Keija Parssinen

March 28, 2020

GRANVILLE, OHIO—I was at an artist residency outside of Chicago when the country began to shut down. In early March, the twelve other artists and I arrived from across the country in a state of low-level dread, with our tiny bottles of airport hand-sanitizer and sardonic plague quips. We were strangers who talked about our work at communal dinners and hosted post-dinner professional development workshops about Scrivener or the publishing industry.

Within a week, the tone changed, an indelibly swift lurching from dread to panic. The residency’s office staff disappeared. One of the neighboring residents took off for home in the middle of the night, his 2 AM shower startling me awake. Bulk hand-sanitizer and rubber gloves appeared as if delivered by nightmare fairies.

We were never told to leave—we were not told much, which led to jokes about feral writers taking over the property—but, one by one, we departed for places remade by the virus. I missed my family and could not sleep, but my husband and I agreed I should stay to try to finish my book, because it might be the last opportunity to do good work if Ohio schools shut down. Our group dinners became smaller, berserk with laughter.

One day, a red fox paused in front of a window, the elegant fact of his body familiar and reassuring. I listened to a resident named Kevin play “I loves you, Porgy” on the piano in his studio, and I thought about the singing Italians, playing guitar on their rooftops and clarinet from their balconies. I thought of a line from Kaveh Akbar’s poem “The Palace”: “Art is where what we survive survives.”

I cancelled my flight home and rented a car with a resident named Ariel. We decided it would be safer for her to fly home to New York City via the small Columbus airport, rather than facing the chaos of O’Hare. When we walked into the rental place in our rubber gloves, prepared to be thought ridiculous, we were relieved to see the attendant also wore a pair. The three of us laughed ruefully as we wiped down the car’s interior together. The man was conscientious and kind, and before we drove away, we all made little heart shapes with our hands, à la Taylor Swift, told each other Stay healthy, be safe. Once on the road, Ariel and I snacked aggressively and listened to a podcast about Tom Hanks that made us cry.

When we stopped at a small Indiana town close to the Ohio border, we could not find an open restroom. Finally, we located one in a shabby gas station, where the woman working the register was openly hostile, sneering at our rubber gloves. Her expression brought to mind the cannibals in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Maybe that’s unfair, but disaster lands differently with different people. Look at those doctors reportedly now hoarding potential Coronavirus medication for themselves and their families, or Lt. Governor Dan Patrick of Texas telling older people to sacrifice themselves on the altar of the economy.

Once home in Granville, I felt feverish. I took my temperature: 99.1. Shit. I took my temperature fifteen more times that night; it fell to 97.6. Maybe my body was just purging the worry I’d held inside in order to make the journey home.

“Look out the window!” my husband shouted from upstairs the other afternoon. I grabbed my two young sons and we stood on the couch to look. There was a social-distanced dance party happening in a neighbor’s driveway. Quickly, we donned shoes and coats and raced outside. It had been several days since we had seen anyone but ourselves. Someone had parked in the street and was blasting music from the car stereo and dancing with her kids while our neighbor and her daughter jammed along from a balcony.

For a few blessed minutes, I bopped with my three-year-old, and we waved and chatted to our neighbor. When the other woman drove away, she promised to return. She’d honk next time, she said, so we’d know she was there. ■

E. Tammy Kim

March 27, 2020

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK & TACOMA, WASHINGTON—In late February, I went to Oakland to report on the homelessness crisis for the NYR Daily. From there, I flew to my parents’ house in Tacoma, Washington, to write and rest and eat Korean food.

My parents and I had been tracking the spread of the coronavirus in Korea, but we didn’t expect it to migrate so quickly, and dramatically, to the US. Mom works for the state agency that regulates elder-care facilities, and in early March, Covid-19 was detected in a nursing home just north of her jurisdiction. Our household absorbed the growing panic.

When I boarded my flight back to New York, on March 11, I felt uneasy. Would Mom be all right, continuing to work alongside inspectors? Who would take care of her and Dad if they got sick? Could my brother and I fly out West, last minute, if needed? My mother shared these worries, on top of her usual parental concerns.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve exchanged dozens of emails, text messages, and calls, mostly in Korean. What follows is our correspondence, translated, edited, and condensed.

March 11

Tammy: 잘 도착했어요! Landed safely!

Mom: 고맙다! Thanks!

Tammy: 사무실엔 별일 없어요? Everything okay at work?

Mom: 그렇지 뭐. 두 직원 오늘 부터 paperwork는 집에서 하게 돼서 한 시름 좋았지. I guess. I got two of my employees approved to do their paperwork work from home starting today, so one thing down.

Tammy: 수고 Good job. [two gold medal emojis]

March 12

Tammy: 미안. 지금 친구 집 Sorry [missed your call]. Friend’s house.

Mom: 끝나는대로 전화해. 한국은 안되 When you’re done, call me. You can’t go to Korea [for reporting].

Tammy: 괜찮은데 But it’s safe.

March 13

Mom: 태미야 팽이버섯 먹지 마. 미국에서 4명 죽고 30몇명이 아프데… (Tammy, do not eat enoki mushrooms. Four people died and 30 something people got sick in the US…)

Tammy: 오!! ㅇㅋ Oh!! OK

Dad: See attached file! “미국서 ‘한국산 팽이버섯’ 먹고 4명 사망 … 한국인은 멀쩡, 왜” “In America, 4 die after eating ‘Korean enoki mushrooms’… so why are Koreans okay”

March 14

Mom: [article link] “문 대통령, 오늘 대구-경북 특별재난지역 선포” “Today, President Moon declares Daegu-North Gyeongsang a special disaster zone”

Tammy: 이 달 말경 한국을 방문할 계획… 대구 At the end of this month, planning to go to Korea… Daegu.

Mom: 안 갔으면 좋겠는데… I really wish you wouldn’t…

March 16

Tammy: 엄마 출근하지 마십시오!!! Mom please don’t commute!!!

Mom: 한국에 갔다가는 돌아오는 비행기 없어 If you go to Korea you won’t be able to catch a flight back.

Tammy: 출근은?? What about your commute??

Mom: ㅌ 식당 어제 밤까지 일했는데 오늘 부터 닫았대. 집에 오라고 그랬는데 모르겠어 Your brother worked at the restaurant until last night, but it’s shut down as of today. I told him to come home but I don’t know if he will.

Tammy: 네. 저한테도 연락이 왔어요. 사무실에 갔어요? Yes. He told me. Did you go to the office?

Mom: 모든 field manager가 다 출근을 하고 있고 그 어느 때보다 책임이 막중한데 나만 집에서 하겠다는 게 좀 그래서 아직 말을 못하고 있어. All the field managers are in the office, and we have more to do right now than usual, so I feel like I can’t ask just for myself.

Tammy: 애고 그래도 Argh, come on.

Mom: 너무 걱정 마. 주말에 7마일씩 걸었어. 건강을 유지하려고 하니까. ㅌ 일도 걱정할 거 없어. Don’t worry so much. We walked 7 miles Saturday and Sunday. We’re taking care of ourselves. Don’t worry about your brother’s situation either.

Tammy: 네. [heart emoji, mask-wearing face emoji] 엄마 근데 나이도 있고 은퇴하신 상태니까 work from home 할 수 있는지 물어봐도 돼요. Sure. But Mom you’re older and you’re technically retired so it’s okay if you ask to work from home.

March 17

Tammy: ㅇㅋ?? OK??

Mom: 조금 아까 M한테 내일 부터 집에서 일해도 되냐고 이메일 보냈어. I emailed M a bit ago to ask if I can work from home.

Tammy: 고마! Thx!

Mom: 그렇게 하라고 답장 왔어 [thumbs-up rabbit emoji] Got permission to go ahead.

Tammy: Wow!@! 다행이다. What a relief.

Mom: ㅌ가 집에 안 오는 게 낫겠다고 해. 이제까지 식당에서 expose 됐는데 우리 나이가 많아서 자기가 가면 우리가 위험해질 수 있다고 Your brother thinks it’s better if he doesn’t visit. He said he probably got exposed at the restaurant and because we’re older it could be dangerous.

March 19

Mom: [article link] “美 여행금지 경보 전 세계로 확대… ‘어기면 무기한 미국 밖에 머물러야 할 수도’” “Warning not to travel to the US, worldwide spread… ‘if not, you might get stuck outside the US indefinitely’”

Mom: 밖에 나가지 마. 거긴 동네도 사람들 많이 다니잖아 Don’t go outside. So many people on the streets in your neighborhood.

Mom: 별일 없지? 우리도 괜찮아. All good? We’re fine here.

Tammy: 네! Yes!

March 20

Mom: [article link] “Why is the New Coronavirus Different?”

Tammy: [alarmed-looking duck emoji]

Mom: [two photos of magnolia trees]

Tammy: Wow!! 그 나무들 Those trees.

Mom: 걷는 길에 목련이 드디어 폈어! The magnolias on our walking route finally bloomed!

March 23

Mom: 태미야, 별일 없니? 밖에 나가지 마 Tammy, you doing well? Don’t go outside.

Tammy: 네! 엄마는? Okay! What about you?

Mom: 오늘 6일째 아직 괜찮아. 이달 말까지 별일 없어야 될텐데. 그동안에 노출됐었으니까. It’s day 6, and I’m fine. I just need to stay fine until the end of this month. Since I may have been exposed while at the office.

Tammy: 괜찮으시겠죠. I’m sure you’ll be all right.

Mom: 그럴거야. Yeah.

Mom: 여기 effective immediately stay at home order 나왔어. We got a stay at home order here effective immediately.

Mom: 한국행 비행기는 3배가 올랐고 살 수도 없데. 유학생, 교민들이 가려고 난리라네 Flights to Korea have tripled in price and are basically unavailable. Foreign students, Koreans living abroad are scrambling to get back.

Tammy: 아 그렇군요 Ah, I see.

March 24

Mom: 태미야, 수퍼마켙에서 비닐봉지 못사용하게 하다가 다시 한데. 개인 재활용 백은 사용 못한데. 바이러스때문에. Tammy, grocery stores weren’t allowed to give out plastic bags but they can again. People aren’t allowed to reuse bags. Because of the virus.

Tammy: Ok!

March 25

Tammy: 집에 별일 없어요? 사무실엔 계속 난리? 뉴욕은 난리 Anything new? Is work still chaotic? New York is chaos.

Mom: 별일없어. 거의 모두가 집에서 전화로… infection control 나갈땐 PPE 갖추고 나가고. 시시각각으로 변하니까. Nothing new. Almost everyone is making calls from home… and when staff go out for infection control, they wear personal protective equipment. Things are changing by the minute.

Tammy: ㅇㅋ. 맛있는 것 드시고. 내일 통화해요. [animated smiling-and-waving bear emoji] OK. Be sure to eat something good. Let’s talk tomorrow.

Mom: ㅇㅋ. 잘자 [emoji of same bear, tucked under covers, asleep, and drooling] K. Sleep well. ■

Adam Foulds

March 27, 2020

TORONTO, CANADA—I go out for what may be my last haircut for some time. The old Italian man I usually see has sensibly shut up shop. Instead of his narrow, sun-faded interior with its few family photos tacked to the wall, landline, and small TV playing sports, I go to the hipster version nearby. This place bristles with manly Canadian bric-a-brac, stuffed fish, mounted deer and moose heads, old advertisements, beer bottles, Playboy centerfolds, painted seascapes. The two barbers are tattooed and bearded and wear leather aprons. All this showy masculinity doesn’t preclude good hygiene, however; they are diligent with their hand-washing and sanitization of equipment. The chair is squirted and carefully swabbed before I sit down. One other customer is here, discussing with his barber prospects for business and the reports of panic-buying in supermarkets. “It’s just selfish, eh? You wouldn’t want to go to war with these people.”

For the first time, I see someone walking past outside wearing a mask.

I attend a Zen meditation via Zoom. Sittings are suspended. The sounds of the wooden mallet and bells are flat, compressed through my laptop speakers. Once the resident monk, or roshi, is seated, he is out of shot and the feed is of a silent and apparently empty meditation hall, the cushions neat and unoccupied in their places along the walls.

The flat blue-gray expanse of Lake Ontario. My gaze races out to an indigo line of horizon at the base of a sky of unbroken pale cloud. Newly arrived wild ducks—buffleheads and hooded mergansers—circle in small groups near the shore. The first signs of spring, though everything is still leafless. Beautiful irrelevance. The virus is a human problem; nature feels more than usually tilted away from us.

Along the boardwalk there are people walking, jogging, walking their dogs, singly or in couples. They are sensibly spaced, intentionally or not. I keep my own distance: all of them are potential carriers. It feels new, this very old way of looking at the world and fearing the unseen, suspecting dybbuks and devils inside people, lurking on door handles, hovering in the air. Only, we know what our devils look like—innumerable translucent orbs surrounded by brush-like protrusions—and we know that they’re real.

Ontario declares a state of emergency. Scrolling for new news, articles, information, clicking through, clicking back. Maybe now, though, after five years of this, I can stop. I have briefly the abstract sensation that our lurid reality has been thickening and thickening and has now solidified into this one thing, this situation, general paralysis, everyone immobilized in their homes.

Also reaching critical mass is a feeling of obsolescence. Writers have been complaining for some time about a reality that’s too rapid and extreme. One of the witnesses to nuclear disaster in Svetlana Alexievich’s Chernobyl Prayer comes to mind: “Sometimes I have a blasphemous thought: what if our entire culture is nothing but a chest full of old manuscripts? Everything that I love…”Last week is a long time ago. Italy has shut down the region of Lombardy. Our surprise at that is now quaint.

I wake up from a nightmare in which I arrive at the moment of death. I’ve been having these now and again for some time, since well before the pandemic. The theme of the nightmares is suddenness and implacability. It is always violent death at human hands. Attempts to hide or fight back are useless. There is no time to be ready in any way. I understand that I have to die in the middle of everything, of life, leaving so much unfinished, unrealized, and that this is the nature of death.

Lines outside the supermarkets. At least half the faces masked. Many people wearing surgical gloves. It is frustrating to be in the opening minutes of a disaster movie unable to fast-forward to see what happens, what is coming to London, to New York, to Delhi. ■

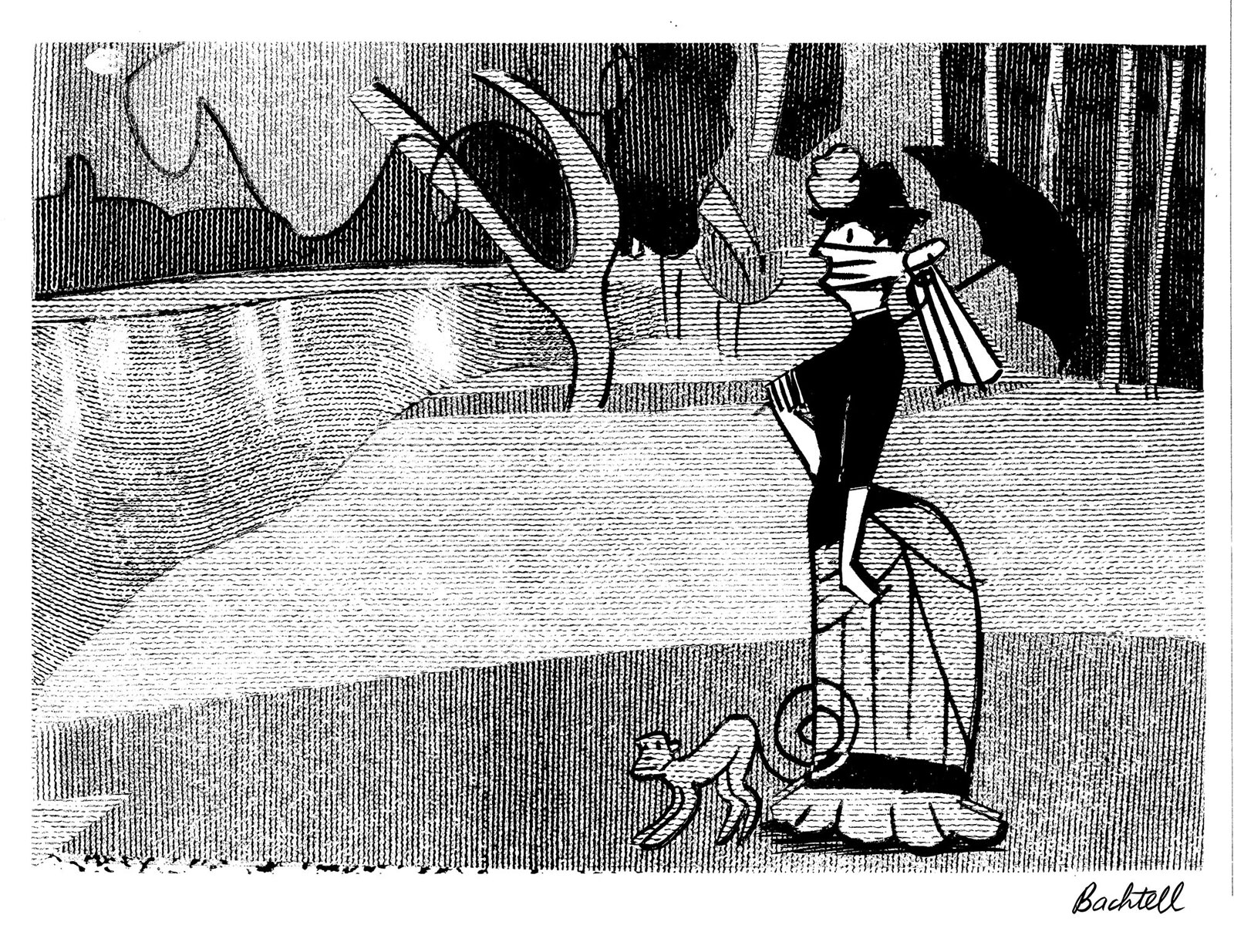

Tom Bachtell

March 27, 2020

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS—Illinois governor J.B. Pritzker and Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot have asked the state’s residents to shelter in place, practice social distancing, and do solitary exercise. The reassuring, thoughtful manner of their radio addresses suggest those of FDR and LaGuardia in their reach and gravity and sense of community—they describe both what government is doing for its citizens and what is expected of citizens by government.

I’m grateful I’m still allowed access to my office, where my drawing equipment is. The el trains, the streets, my office building—all are relatively empty. I spend a lot of time checking in with friends and family, writing and receiving messages. Every communication resonates with some degree of anxiety. I realize that people count on me to maintain my sense of humor and good cheer. I worry about my livelihood, about everyone’s livelihoods—not least the artists, musicians, dancers, and others whose ways of securing an income have suddenly been upended with the closure of museums, galleries, and performance spaces.

I’m not surprised that I miss close physical proximity to others. I used to go swing dancing to The Fat Babies at the Green Mill every week. Now I put on Fats Waller and do sit-ups and planks and stretch alone. I think about all the different ways I try to connect with people—through my drawings, through reading, through humor and ideas tossed around with friends. I can feel myself and others trying to hang on to a world we love and recognize, and wonder what it will look like when the pandemic is over. ■

Ivan Sršen

March 27, 2020

ZAGREB, CROATIA—I woke up with a strange feeling that something was missing, but after a couple of seconds I realized that my breathing was too shallow. I felt as if someone had sat on my chest and wrapped their fingers tightly around my throat. The next thing I remember is the corridor of the Dr. Mladen Stojanović Hospital, and a few nurses wheeling me into the ward. A doctor prepared a large syringe with sedative while two nurses held me down. My resistance slackened as soon as the injection was administered, and the nurses put an oxygen mask on my face.

This scene rushed back into my memory, when I heard about the first confirmed case of Covid-19 in Zagreb on February 25, and I was taken by that same icy fear of death that I experienced as a four-year-old boy, back when I used to get fits of allergic laryngitis, whose occurrence doctors could never predict. Even though I hadn’t had a single episode since the age of seven, I have never forgotten my sense of powerlessness in the hard grip of an illness that almost made me stop breathing.

A month had passed and Zagreb was completely deserted. All unnecessary going-out was banned, as well as any kind of group gathering; everything was shut except for food shops and gas stations. The police patrolled the streets, sending home those who did not obey the rules. People queued outside pharmacies, punctuated by two-meter gaps. We had internalized the problem: we had accepted the rules as the norm and a necessity.

I stood on the balcony of my flat, on the sixteenth floor of a high rise, where we had recently moved, and watched the empty crossroads below and the long avenue that had not a single person on it. I felt my affliction had returned. It would try to sit on my chest and grab me by the throat again. But I couldn’t say anything to my wife and my sons. Would they even understand? No, I couldn’t spread my panic.

So I decided to externalize my problem. I’d keep a diary. The last time I kept a diary was when I was a student. My notes were swallowed into oblivion by my old PC286 and could never be recovered. On the Friday, I agreed with my colleagues that we should work from home, and I felt relieved like one might feel relief before the final battle: I’d stay home, self-isolate, and I’d face my fear—I’d write about it.

I got up energized that Saturday; it was a beautiful, luminous day. I spent the day writing and sending emails to all those whom I’d not been in touch with over the past week, and in the evening I made an omelet with cheese, my sons’ favorite dish. They weren’t too dismayed at school’s being cancelled. We played a board game and watched the news, which informed us that, of all the European countries, Croatia was seeing the slowest spread of the coronavirus. We went to bed almost joyous.

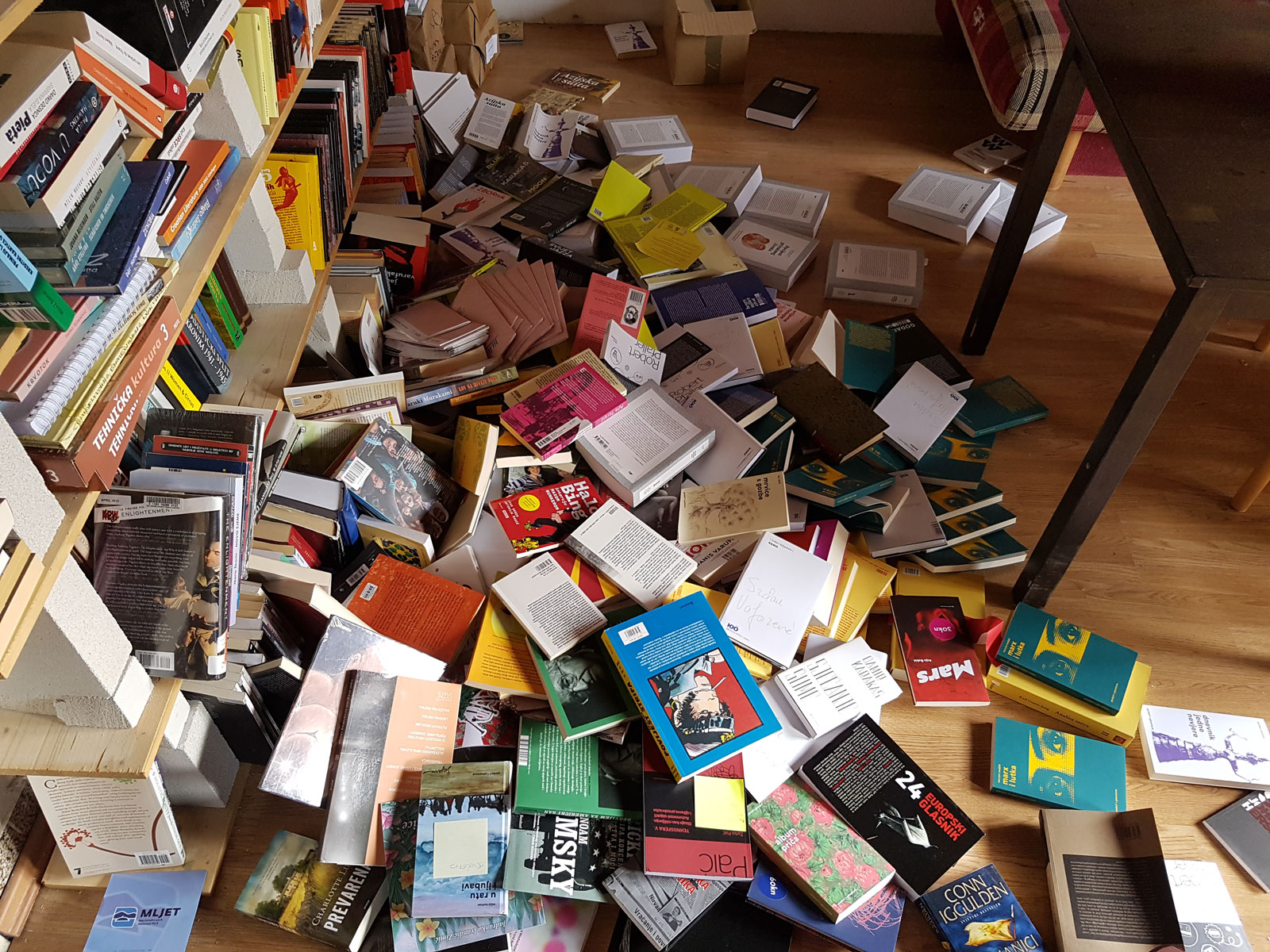

The next morning, I woke up shivering with panic, unable to breathe. I thought that it had come to get me and I was being held in its deadly grip. But then the whole room was shivering. My wife got up and I, paralyzed with fear, watched her standing and swaying together with the furniture in our bedroom. I thought I was dreaming, and concluded that since it could not kill me in my sleep by suffocating me, it had come to kill me by knocking down the entire building. But then the shaking stopped and our high rise, along with the ninety-nine apartments at its core, softly swayed for another ten seconds, like a dandelion in a gentle breeze.

Following the first tremor, we saw dust clouds rising from the nearby collapsed roofs, and we raced down onto the street just before the second, equally powerful quake hit again. In contrast to the previous days, the streets were full of people. They tried not to get too close to each other while keeping away from the tall buildings, which everyone feared could crumble upon them.

A friend from Athens, a poet and nurse who has been working in a hospital ward treating coronavirus patients, sent a message to check how we were, because she had just heard the news about the earthquake in Zagreb. I replied that we were OK, but that everyone was feeling desperate. She responded, saying: “It’s pretty normal for people to be desperate.” ■

Sue Halpern

March 27, 2020

RIPTON, VERMONT—It’s sugaring season here, and most days someone from our household walks through the woods to our neighbors’ sugarbush to collect sap. We have done this for years, but this spring’s haul had special significance: some of that sap was to be made into maple syrup and given to the guests at our daughter’s wedding. There is no way to know if the wedding, scheduled for August, will have to be canceled—or, if it’s safe to proceed by then, who, among the guests we imagined would be there, will no longer be alive. It’s a grim thought with a certain statistical truth to it. We watch the curve of infections soar upward, we hear doctors from Italy and Spain explain that they have had to triage anyone older than sixty—triage being a cursory way to say “let them die”— and we marvel at our own hubris: Who were we to assume that the world in August 2020 would be a world we knew? In that old, familiar world, it made sense to book a venue more than a year in advance, hire a band, and debate pies versus cake. In that world, which still existed less than three weeks ago, we could spend an hour talking over details that seemed important then and forgettable now. It’s almost embarrassing.

One day last week we roasted a turkey, and from the turkey we made stew and sandwiches and stock. It fed us for days. Afterward, I saved the wishbone and let it dry out until we could do the thing we did as children: make a wish, break the bone, and believe that whoever got the bigger part would have theirs come true. There are so many things to wish for right now: that the curve flattens, that we don’t get sick, that no one we knows gets sick, that no one they know gets sick, that there will be enough ventilators and ICU beds, that a vaccine will be developed, and on and on and on. I offered to break the wishbone with my daughter, but she would not humor me. “There are no bad wishes right now,” I said, though we had just been talking about how Donald Trump was hoping Americans would stop self-isolating and get back to work, public health be damned.

Still, we comfort each other by acknowledging how lucky it is to be in a beautiful place where we can go outside, walk for hours, and not encounter anyone—a place remote enough that it’s not “self-distancing,” it’s just the way it is. We live in the mountains, where we are always prepared for weather that knocks out the power or washes away roads, cutting us off from the larger civilization. (It did not take a pandemic to introduce us to dried beans.) When that happens, neighbors check in on each other, often walking through deep snow or picking their way over blowdown to do so. Something like that is happening now. A Google doc is circulating through our town of 523 people, to identify who needs help and who can give it. It’s a reassuring antidote to those photographs of big cities, where people are lining up to buy guns.

My daughter wants to know if I think the wedding will still happen this summer, and I have to tell her that I have no idea. No one knows what’s coming. ■

Michael S. Roth

March 27, 2020

MIDDLETOWN, CONNECTICUT—In early March, at a faculty meeting, the coronavirus was third on my list of agenda items, after facilities improvements and fundraising progress. I mentioned a colleague’s suggestion that Wesleyan, where I am president, should cancel the upcoming Spring Break so as to finish the semester early. The room erupted in laughter, and I joined in. Students have their theses, professors their research—ridiculous to contemplate disrupting everyone’s plans.

But within days, I found myself seriously considering suspending classes for the semester. Students caught wind, and I was bombarded with emails and petitions urging me not to panic or cave into a “mob mentality”—my normally leftier-than-thou students sounding almost like Fox News in urging against over-reaction to an illness “quite like the flu.” They mounted a letter campaign urging me to take a “moral stand” against “mass hysteria.” Parents of student athletes angrily protested the prospect of cancelled events. But the threat of an overwhelmed health care system in our small city, the fact that residence halls resembled cruise ships as sites for contagion, kept me up long into the night.

On March 11, we suspended in-person classes. A week and a half later, 90 percent of our students have left campus, the library and classroom buildings are closed, faculty are preparing to teach online, and all but a small number of employees are working from home.

Moving to an online mode addresses only a fraction of a university’s concerns. An undergraduate writes me to say she has a real connection with a psychiatrist in town, is on a new medication—how can I ask her to leave campus? Hundreds of our students have underlying health conditions that put them at risk. About 20 percent of them are from low-income backgrounds, and they depend on the school for housing and food. Many more rely on us for jobs, and now we don’t have nearly as much work on campus to do. We have responded by adding resources to our Emergency Fund to help with travel, housing, and food, but how to respond to every need? A group of students started a GoFundMe page. Lots of fear on top of anger at how inequality intensifies suffering.

Some parents have written to me because they don’t know how to keep their adult children amused. Some students write because they don’t know where their next meal is coming from.

Wesleyan is a residential school, one with a strong sense of engaged and community-based learning. Now, faculty are giving seminars and singing lessons at a distance, but we all know that the fabric of liberal education here comes from mutual entanglement. I wrestle with the fact that our obligation to our students doesn’t go away when we move to online classes, but our ability to take care of them changes. We will face the educational cost of social distance.

This past weekend, students still on campus picked up meals from the dining hall to bring back to their rooms. A undergraduate from China reassured me that he would be okay, while another sent me a message about my health after hearing me briefly cough on a webinar. I crossed paths with some of the last people preparing to leave campus. I met an African-American dad packing up the belongings of his second child at Wesleyan. He said that he had waited eight years to see his youngest walk up at Commencement. We shook our heads.

My own daughter, Sophie, is not so far from college-aged. Last week, my wife, Kari Weil, who also teaches at Wesleyan, picked her and her partner up from Brooklyn, so that they could “isolate” with us on campus. Sophie is a first-year elementary school teacher, accustomed to spending days with sniffly kids. Her immunity, she says protectively, is a lot stronger than that of her sixty-something parents. I haven’t seen much of her, as we live together yet apart, but I can hear her down the hall, chatting online with the children back in Brooklyn. We wash our hands and wait to be together again. ■

Ben Mauk

March 26, 2020

PENANG, MALAYSIA — Our train pulled into Butterworth at dusk, two hours behind schedule. We walked with the other passengers (half without masks, at least one or two coughing lustily) to the ferry launch across the water from George Town. Although there couldn’t have been more than twenty people waiting to board, there was somehow a crush at the gate. Once on deck, however, social distance was restored. The strait was calm and sunset pink. On our port side was Jerejak Island, where they tore down the old leprosarium to build a beachside resort.

C and I had spent February in Malaysia’s rainforests, visiting outposts of hunter-gatherers and autonomous Temiar villages. When we left for Penang, on March 10, we had just finished three days of research in Ipoh, an old tin mining boomtown. With its covered arcades and concubine alleyways, Ipoh was picturesque but eerie, like the photos going around of the Great Mosque of Mecca’s empty white floor, or the clarified, unsedimented canals of Venice. We assumed the restriction on flights from China was the reason shops were quiet. Wheelbarrows of durian had no buyers. But reality had not really set in. We were sharing our hostel with a suntanned family of five from Perth, halfway through a vacation they seemed grimly determined to enjoy. On the ferry, I remembered the young mother coughing into the kaya jam one breakfast, and instinctively felt my lymph nodes. Nothing.

Some writers are already shut-ins. At the moment, I envy them. Last December, I signed a contract to write a book about communities in extremis—refugees, nomads, smugglers, separatists—people living literally at the furthest reaches and in the shadow of the state. It would involve six months of travel across Southeast, South, and Central Asia. We sublet our apartment in Berlin and flew to the Philippines on January 10, eleven days after the World Health Organization announced the discovery of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan.

Two days later, Taal Volcano erupted outside of Manila, coating the parked cars in Poblacion with a gossamer of white ash. Thousands living around the caldera were evacuated and N95 face masks were sold out for weeks in pharmacies as far south as Zamboanga, 500 miles away. What a disaster, we thought at the time. On January 15, as we met with a veteran political prisoner in the Cordillera, the crater was still smoldering and the head of China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention was declaring to the world that “the risk of human-to-human transmission is low.”

Disembarking the ferry in George Town, we hailed a taxi using an app called Grab. Our driver was wearing a blue surgical mask and listening to “Memories” from the Original Broadway Recording of Cats. Later, C made the observation that this was the last piece of music we would hear ambiently, in public. The cab dropped us at our home stay: a studio apartment on the twenty-ninth floor overlooking other mostly vacant high-rises and mazes of stilted homes by the shoreline. Rich atop poor. It’s a view we have come to know well.

The next day, we went to see the Chinese clan jetties, built a century ago to house migrant dockworkers along Weld Quay. Men in gas masks walked along Chew Jetty with disinfecting guns that looked like leafblowers, blasting hot air and chemicals into open living rooms. We got back to the apartment and begged our host to extend our stay through the end of March, self-quarantining that very night. A few days later, lockdown began. Security guards ushered stragglers off the beach. The army was deployed to enforce road blocks; just today, C received a text message in Malay: “Photographs showing ATM / armored vehicles on the road are fake news that is intended to cause public anxiety.” The local news channel ran a video of a cardiologist in George Town arguing with a cop over the right to jog.

Still, we took a walk by ourselves to the fisherman’s wharf two days ago. No one stopped us. There was no one to stop us. As we walked, I found all the usual travelers’ exotica transformed into apocalypse porn: packs of wild dogs, crumbling piers, weatherworn temples. Normal wildness and rot was suddenly portentous. The world had retreated to the furthest reaches. Everywhere is in extremis. Malaysia’s Movement Control Order is set to end on April 1. Friends in George Town warn us it will probably be extended. Either way, we don’t know where to go. ■

Martin Filler

March 26, 2020

SOUTHAMPTON, NEW YORK—In the back of my mind I’ve always considered the small Shingle Style house my wife Rosemarie and I bought twenty-five years ago in the village of Southampton on Long Island’s South Fork to be our safe haven if anything catastrophic ever happened to New York City. Such a disaster occurred on October 29, 2012, when Superstorm Sandy caused the East River to flood and rendered our Upper East Side apartment building uninhabitable for six weeks, during which we decamped to Southampton, grateful to have that refuge, unlike the many far unluckier victims whose sole dwellings were destroyed.

This February, we visited our son and his wife in Honolulu and comprehended the gravity of Asia’s Covid-19 pandemic because travel from Japan—which accounts for nearly 20 percent of Hawaii’s tourism industry—had plummeted. We reckoned that globalization would make it only a matter of time before the contagion hit the mainland US, and, upon our return, began making plans to ride out the danger in Southampton, since both our age and my fraught medical history put us at increased risk. I can write anywhere and Rosemarie can happily garden for hours on end as Spring commences, so what could be bad about a protracted Long Island hiatus? Though what if this turns out to be a much longer siege than the aftermath of Sandy?

Once we arrived in Southampton on Friday, March 13, we could see that we were hardly the only second-home-owning New Yorkers who’d decided to outlast the plague in these less confined surroundings. It initially feels like a premature, unusually chilly summer season, and local real estate offices report a sudden spike in house rentals for immediate occupancy rather than beginning as usual on Memorial Day weekend.

Although we’ve always preferred to think of the Hamptons as being inhabited not just by gazillionaires but also people like us—writers, academics, artists, and curators—the ugly truth is that this is Trump country. The fact that our Republican US congressman, Lee Zeldin, is a fervent Trumpist reflects the unlikely coalition between the region’s disgruntled white working-class residents, whose pickup trucks and utility vans are often plastered with Trump bumper stickers, and plutocratic New York businessmen who use their part-time Hamptons domiciles as legal residences and vote via absentee ballot.

The latter contingent includes several protagonists of the Trump administration, among them Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross. His third wife is a third-generation Southampton socialite, and their house is a three-minute drive—but a universe away—from ours. Last summer, a multimillion-dollar fundraising event that Trump attended at the Southampton estate of the New York real estate developer Stephen Ross (the prime mover behind the dreadful Hudson Yards) spurred a social media-driven rash of membership cancellations at Soul Cycle and Equinox, two fitness chains that he owns.

The other side of this high/low equation is the shocking depth of race hatred among working-class whites in Suffolk County, many of whom descend from families who fled the increasingly multicultural outer boroughs of New York City from the 1950s through the 1970s. And the pandemic seems to have exacerbated class conflicts that have long simmered just beneath the surface in the Hamptons.

At the start of every summer, it seems, The New York Times runs a laughably inaccurate Hamptons-envy article—a rote rehearsal of the same dated celebrity names (Calvin Klein, Stephen Spielberg, Christie Brinkley) with cartoonish memes of Lamborghinis and Maseratis clogging the roadways and yachts three-deep in the marinas. But last week the Murdoch-owned New York Post published a prime specimen of socially divisive invective: an opinion piece by Maureen Callahan headlined, ‘“We should blow up the bridges’—Coronavirus leads to class warfare in the Hamptons.” Callahan alleges that the city’s Covid-19 refugees were bringing the virus with us and polluting the year-round community, as if there hadn’t likely been enough pre-symptomatic exposure to ensure the spread of the disease out here already.

Nonetheless, we continue to witness the expected grotesqueries that exemplify life in the Hamptons of the so-called 1 percent. The Chase Bank branch in Southampton lately caused a stir by refusing to cash a check for $30,000 because they feared they’d run out of ready money at the start of a weekend and so limited withdrawals to $10,000 per customer. What one could possibly want with that much paper money beggars the imagination, unless it was meant for very high-stakes poker games or to pay a big staff of off-the-books servants at one of the colossal oceanfront mansions on Dune Road.

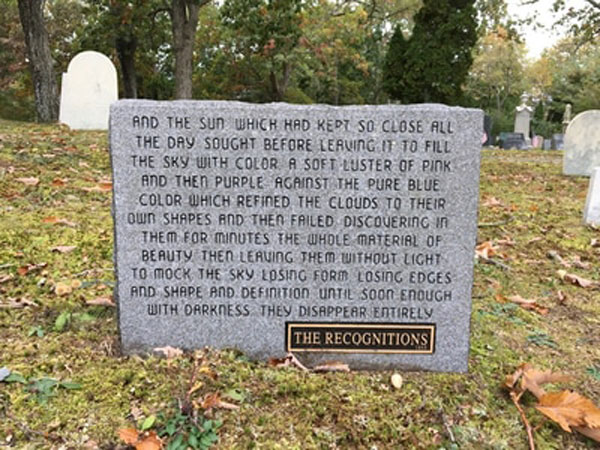

For years I’d fantasized an updated Decameron scenario like the one we’re now living though, with ourselves in the role of the Florentine aristocrats who fled from their city palazzi to their villas in Fiesole to escape the Black Death. However, I doubt that any present-day Hamptons literati—now that so many of the best ones, including our reliably mordant and cheerily fatalistic friend William Gaddis, are dead—will produce anything approaching Boccaccio’s plague-time classic.

If worst comes to absolute worst and all our precautions have been for naught, our designated burial plot is contiguous to Gaddis’s in Sag Harbor’s historic Oakland Cemetery, a few miles northeast of Southampton. Not far from his tombstone, which is inscribed with an excerpt from his masterwork, The Recognitions, lies the grave of the incomparable George Balanchine. Further away are those of two more of our favorite artists, Gordon Matta-Clark and Stephen Antonakos. I consolingly consider them our cosmic cocktail party, though I’m not eager to join in anytime soon. ■

Eula Biss

March 26, 2020

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS—There aren’t many cars on the road, but the proportion of Amazon delivery vehicles feels ominous, my husband says. “If there’s going to be a junta,” he jokes, “it will probably be led by Amazon.” This is our first week under the Stay at Home order, and our second week staying at home with our son. I take him outside for mandatory exercise every morning. Today we jog a couple blocks to the high school to run sprints on the track, but the chain-link fence around the track is locked with a padlock, so we run sprints on the empty parking lot. My son was born in 2009, a month before the first novel H1N1 influenza infections were reported to the CDC. The possibility of hospitals becoming overwhelmed and essential medical supplies becoming scarce—the possibility that has now become a reality—is what made those early reports of a novel H1N1 virus, the subtype that caused the 1918 pandemic, so alarming to experts in infectious disease.

“This is not unprecedented,” I said to a friend last night on the phone. Maybe the scale of the worldwide response to Covid-19 is, but the global spread of a devastating disease is not. And neither are the strategies we’re employing to slow that spread. Quarantine is an old word, and Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year, a fictional account of the 1665 epidemic of bubonic plague in London, reads like a prologue to this pandemic. The numbers reported in the weekly Bills of Death were low at first, Defoe writes, but then grew exponentially. The rich fled the city, and the sick were forced to stay in their houses.

“Pest houses,” I thought when I read the first reports of the temporary facilities in China where people with symptoms of Covid-19 were being held. In nineteenth-century America, a pest house was where people with smallpox were forcibly isolated. The historian Michael Willrich writes in Pox: An American History of children who were dragged away from their mothers to be taken to pest houses, where they most often died.

The playground two blocks from our house is almost always full of children, even on a cold March day like today. I’ve seen children on that playground in freezing rain, in polar vortexes, and in searing heatwaves. But today it’s empty. My stepmother tells me about a summer during her childhood in the Bronx when she wasn’t allowed to play in the sprinklers in the public parks. There was a polio epidemic that summer. What polio has in common with Covid-19 is that people can carry and transmit it without showing symptoms. About 70 percent of people infected with polio show no symptoms and another 25 percent have mild symptoms such as a fever and a sore throat. One in two hundred infections leads to paralysis. My stepmother knew a boy across the street who was in a wheelchair and a girl at school who walked with a limp.

The forbidden sprinklers stood at the center of large concave circles of concrete where they sprayed showers of cooling water. “Was that summer hot?” I ask my stepmother now. “Summers were always hot,” she says. Eventually, she stood in line in the gymnasium of her school, where something that looked like a gun was used to give every child a shot in the arm. That was the Salk vaccine. Later, she would line up again to receive a sugar cube on her tongue. That was the Sabin vaccine. We now use only the Salk vaccine in the US, but the Sabin vaccine, which is less expensive and easier to administer, is used in other countries. “You got both?” I ask her. “Oh yes,” she says, “I got both.” ■

Richard Ford

March 26, 2020

EAST BOOTHBAY, MAINE—I think these times feel stranger elsewhere than here in small-town Maine, where I live. Life here feels familiar—perversely, almost easy, if admittedly factitious. Just not bad on an hourly basis.

My wife does her best to curry a useful sense of danger and threat. (I don’t mean this as I see it reads: I’m not complaining, I need reminding.) But I don’t feel threat strongly—even as I wash my hands, steer clear of others (not her), disinfect my car-door handles and grocery items, and avoid the president’s daily rants.

In the way in which there’s no such thing as a false sense of optimism, that trees falling in the forest haven’t fallen, that the worst sex is still good, there may be no danger to one’s self if one doesn’t feel it. This is, admittedly, an old-person’s existentialism (although it may be a young person’s, too). Still, danger, all by itself, seems inert; it’s the consequence of danger that causes trouble. It’s like falling: the fall’s nothing, it’s the sudden stop at the end that’s to be feared.

How we manage our sense of consequence is the task at hand—and it’s not an unwriterly task. On the one hand, of course, it’s what we do (wash, avoid, ignore) that matters; but it’s also what we say and think and write and notice and make ourselves willing to hear that—assuming we don’t croak—will matter surprisingly much to us when this is all over and done with. ■

George Weld

March 26, 2020

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK—On Friday, March 13, at least one owner on a restaurant-industry message board was still making jokes: “The mayor says to keep the restaurant half empty? I’d be happy to see it half full!” All week business had been abysmal. For us at Egg in Williamsburg, it had been the worst five days in at least twelve years. Our servers were on edge from making no money; the cooks were bored. We’d tried to drum up business by Instagramming the details of our cleaning protocols. We gathered excitedly around our new sanitizer dispensers and marveled at being rich in toilet paper. We were all aware that there was a disaster brewing, or already afoot, but I hoped it would ask no more of the restaurant than any disaster does: simply that we stay open, tough it out, feed people, and let them feel normal for at least the duration of a meal.

On Saturday, the restaurant was buzzing with life. Aside from the 50 percent capacity rule, it was almost business as usual: hangovers to soothe, reunions to host, babies to feed. Customers seemed unconcerned. Our staff was happy to be back in action. If there was darkness creeping around outside the restaurant, inside it was—mostly—normalcy and joy.

But on Sunday morning, the sight of crowds no longer cheered me up. Something had changed overnight. It’s hard to say what was different: a little more news of contagion and death, a little more evidence of governmental incompetence, a few more warnings against contact with others.