WASHINGTON HEIGHTS, MANHATTAN—When word came on the evening of March 15 that the city was finally closing public schools, my relief was laced with panic. My husband and I still have our jobs, can both work flexibly from home, and share the responsibility of schooling our two kids, first and third graders at a dual language Spanish/English public elementary school. Compared to my brother, who makes his money delivering food on a bike for Uber Eats while parenting, and other invaluable low-paid workers like him, we’re lucky. Our kids don’t rely on the school for food, like a lot of their classmates (whose families may now pick up “grab and go” breakfast and lunch from the cafeteria). We aren’t sick—yet. Yet even for us, the lucky ones, the school closure felt like a grim prognosis.

Our kids’ school needed a week to get its remote learning plan in place. Until then, we were more or less on our own. How the hell would we divide the labor of home-schooling with working remotely from home—in a three-room apartment? How would I, as the mother, guard against shouldering the bulk of this labor? How could we pretend to be satisfactory elementary educators, with no training whatsoever? When would things go back to normal? I took a breath for some perspective; tried to relinquish control. What had we really been sentenced to? Quality time with our own children. The opportunity to cook and eat together, check in with our neighbors, cancel everything we didn’t need to do, including many things we never honestly wanted to do in the first place.

I decided that with this gift of time, we might teach our kids the things we have not yet gotten around to teaching them: how to tie their shoes, ride bikes, and tell time. Here was our chance to teach to their interests, pay them the kind of individual attention they can’t get in their overcrowded classrooms, listen to them, and ease the burden of their overscheduled lives. Maybe, if we slowed down and gave the best we had to give, they would even look back on this as a happy time. That night, the third grader lost a molar and I pretended to be the tooth fairy. I hoped I wasn’t deluding myself.

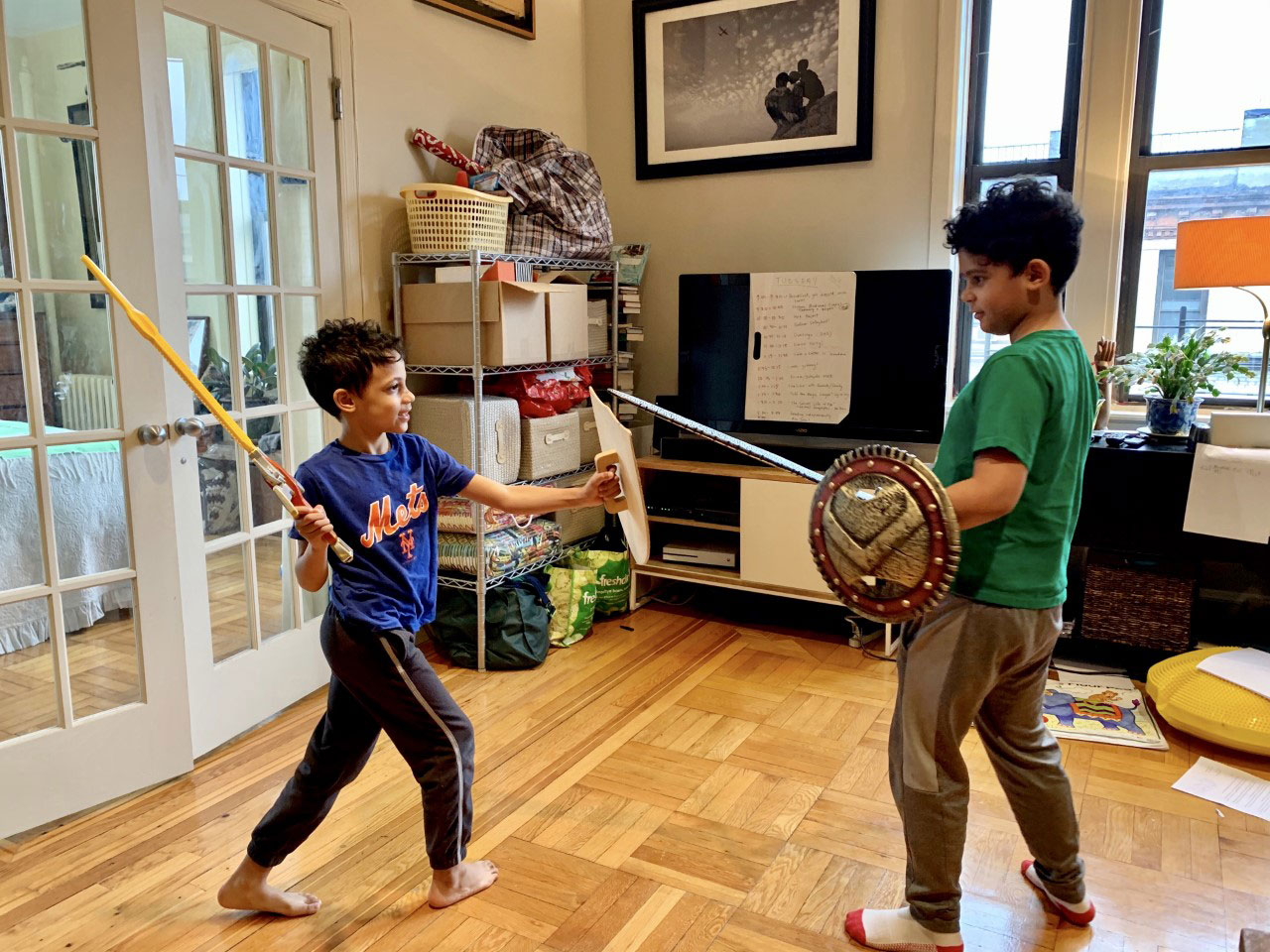

The next morning, we wrote out family rules cobbled from what other parents were sharing on social media, listing why we were isolating, what we couldn’t do anymore, and what we could. Then we asked our children what they wished to learn. The third grader was relieved he no longer had to take the state test planned for the end of the month, which had been giving him anxiety. He said he wanted to know about the civil war, medieval history, and how to become a knight. The first grader said he wanted to know about “how a person runs fast”—and also, hedgehogs.

Taking our cues from them over the course of the first week of home-school, we taught lessons on feudalism, the plague, the value of money, the importance of sharing it—and, of course, hedgehogs. Each morning, we taped a schedule over the TV screen. They wrote letters to each of their grandparents. Their father conducted their daily Spanish lesson on Duolingo. Art class was led remotely by Mo Willems, author of the “Elephant and Piggie” series, during live Lunchtime Doodle sessions out of his studio every weekday afternoon of the crisis, God bless him. On March 19, he drew the date upside down. “Today is March 61,” he said, before talking in simple terms about how waiting is hard.

We disappointed our kids, repeatedly, with reminders that they would have to wait to see their friends. We also made cardboard owls and caterpillars out of the recycling, and bowled using empty two-liter soda bottles as pins in the alley where our building keeps its trashcans. We tried each other’s patience. We grew bored. We played board games. We cuddled and roughhoused. We baked a sweet potato pie.

On Wednesday, during “recess” in a nearby park, we ran into a dad we knew, sipping a bourbon Bloody Mary from a thermos while his kid went in circles on a Segway. Meanwhile, our kids scampered over the boulders near a weeping cherry tree. Through the veil of the tree’s pink-blossomed branches loomed the towers of the local hospital ten blocks away. It did not have enough beds.

On Thursday, I went to pick up the children’s course packets and instructions for the new online curriculum at their school, a ten-minute walk from home. Parents were lined up in the auditorium, then allowed in groups of five to collect the materials, including laptops for those who needed the technology. A few wore masks. Our wait at the edge of the stage felt long, and somber. As we stared at the empty chairs where we’d sat for a recent talent show and the winter concert, one mother shared that she was working from her parked car—it was impossible to get anything done at home with her kids climbing the walls. Another asked about the food supply chain, in Spanish—did anyone know if it was secure?

Advertisement

By Friday, I was exhausted by my new job and convinced that public school teachers should be paid a billion dollars a year. I had taken their service for granted, undervalued their resourcefulness, fortitude, patience, and energy. And while I was struggling to perform a fraction of what they did, they were training hard, still showing up at work at risk to their own health, to learn the online procedures on short notice and set up new platforms for the city’s 1.1 million public school students, with all kinds of hiccups to be sorted out, and for the most part with little guidance. Surely, they were running on fumes, too.

“This isn’t sustainable,” said a neighbor, a single mother of twins. She was working remotely at night, after her girls finally fell asleep at 11 PM. I was doing the same, but didn’t admit that my kids went to bed at 8 PM. Under the circumstances it would have felt like bragging.

There was little to distinguish the weekend from the week, except that we let the kids watch a lot more TV. On Saturday, the third day of spring, we walked them southward along the Hudson River beyond the little red lighthouse under the George Washington Bridge. Amtrak trains sped past, sounding their horns, appearing empty. Everywhere—life. Dogwood. Daffodil. Onion grass. The sun felt magnificent. I pointed out the edible plants they could forage. “You need to know this,” I said, naming every blooming thing.

On Monday, they started online learning, using Google Classroom. The first grader’s teacher, Miss Peggy, conducted a morning meeting. The livestream was glitchy at first, with twenty-odd six- and seven-year-olds talking all at once, their digitized faces shuffling like cards, but the children looked ecstatic to see each other again. Miss Peggy reached out her hands, in greeting. She’d always seemed unflappable, but now, looking at her on the screen in this moment of chaos, she seemed beatific, and I knew there were hundreds of thousands of saints like her on hundreds of thousands of screens across the country. “Good morning, my loves. Today is Monday, March 23rd. I wish that I could hug you all.”

That is when I went into the bathroom, shut the door, and finally cried.