This is the current edition in a running series of dispatches by New York Review writers that is documenting the coronavirus outbreak with updates from around the world that began March 17–22 and continued March 23–29.

—The Editors

Ian Johnson in Beijing and London • Tim Flannery in Sydney • Liza Batkin in Rhinebeck • Carl Elliott in Auckland • Edward Stephens in Athens • Jamie Quatro in Chattanooga • Ali Bhutto in Karachi • Nicole Rudick in South Orange • Andrew McGee in New York • Danny Lyon in Bernalillo

Danny Lyon

April 5, 2020

BERNALILLO, NEW MEXICO—A few nights ago, I phoned my old friend, Ira Churgin. In 1961, we were ancient history students at the University of Chicago. Ira’s roommate was Bernie Sanders. In October of 1962, we all crowded into Mandel Hall to hear Professor Hans Morgenthau explain the Cuban missile crisis, about to reach its climax. That night, we students walked home together in the dark, wondering if a nuclear war was about to start.

There we were, all age twenty, thinking our lives were about to end. In my course on European history, my professor liked to say that the outbreak of World War I was “the end of history.” That summer, I hitch-hiked to Cairo, Illinois, to see the civil rights demonstrations there and meet John Lewis, then a field worker for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). I wanted to be a witness to history.

Two weeks ago, I ended my daily trips to buy The New York Times and my weekly visits to grocery store. Nancy and I are afraid to go to the post office. When a FedEx package arrives, I wipe it off with alcohol wipes. The container came with forty tissues; I have twenty left.

I built this house in New Mexico during the height of the Vietnam War. I was trying to get away from New York City, from my neighbors, and from America. It is built off the grid, two thousand feet from the nearest house and road. Made of adobe and dirt bricks, the walls are two feet thick. I cannot help but feel that, in the extravagance of my youth, I built a house for this moment.

“Danny! You’re still alive,” were Ira’s first words to me on the phone. The subject of our conversation was, of course, the virus.

“What is the meaning of this?” Ira kept asking. “They are going to spend a trillion dollars. That is one thousand billion dollars! I don’t get it. What is the meaning of that? Why not two trillion?”

“They just print it don’t they?” I said. Here in New Mexico, we have been told not to leave the state. Cruise ships have stopped sailing. No planes flying overhead. Last week, prisons began to release inmates.

“No one is immune to this. Everyone is going to get it,” Ira said. “What is the meaning of this?” he asked again. “I just don’t get it. You know there were moments in history, when the world completely changed. Like in the Middle Ages. I think that is what this is.”

“After Berlin had been blown to pieces by the Russians,” I said, “with every building in ruins, the German people came out of the basements, many of them women, and picked up the bricks with their hands and cleared the rubble off the streets. When you walk in Berlin today, the sidewalks you walk on are made of rubble. You look down and you are walking on the broken bricks that the survivors put there in 1945.”

In January, before all the lockdowns started, I visited Congressman Lewis and stayed with him in his home in Washington, D.C. He lay in his bed, buried beneath heavy quilts. He has stage-four pancreatic cancer. On my last day with him, I lifted a small DV camera and made a fourteen-minute recording of our conversation. This was, I knew, the final scene of my film on John, which I have been working on for years. The congressman and I were remembering the generation we’d been a part of, a group that changed history.

“Where are they now?” I said, and laughed.

John looked at me, and said, “They’re on their way.”

“That’s good,” I answered.

“Another group is on their way,” he said again.

“That’s great,” I said. “I’m going to stop this,” and turned off the camera.

When this horror passes, and it will, will the survivors accept a new way to live? The party is over. Our civilization is coming to a grinding halt. Is this the turning point? Will we emerge into a new and better world? ■

Andrew McGee

April 5, 2020

NEW YORK—My father was a thirty-year commercial airline pilot after getting out of the Navy, and I wanted to follow in his footsteps. I got my pilot’s license in high school, and after college I eventually worked my way up to flying for a regional airline. The airline business has always been cyclical, and after September 11, 2001, with few job prospects or opportunities for advancement on the horizon, I made the difficult decision to return to school—and to pursue a career in architecture.

Then, in late 2017, as I was grappling with the realities of a divorce and considering the ramifications of my life choices, I began to hear talk of an industry-wide pilot shortage. Air travel had enjoyed a decade of expansion, which, coupled with unprecedented forecasted retirements, meant that airlines were scrambling to fill seats with qualified pilots. In spite of my ten-plus years away from aviation, I soon learned that I exceeded the requirements for the regional airlines, which would be my stepping-stone to the majors.

I was hired in March of 2019 to fly regional jets, and by the end of the year, I had transitioned to the left seat as a captain, assuming the responsibilities of the pilot in command. I felt I had a new lease on life. I called it my comeback tour.

Less than a year in, in early January, I began to hear about the spread of the coronavirus. My colleagues and I speculated about what this might mean for the airline industry, but—like everyone else—I felt the disease was a world away. Then, in late January, the federal government mandated the cancelation of all flights to and from China. Things just accelerated after that.

I typically work about fifteen days a month, but that means I never have a spell of fourteen days (the prescribed minimum recommended quarantine duration) between trips. Although I haven’t had so much as a cough, I feel “radioactive” when I come back from trips, covered in invisible traces of the international airports I’ve visited in the preceding many days.

In early March, the apartment building where I live in Manhattan sent out an email to all residents suggesting that if anyone has been to any airport, they should self-quarantine for fourteen days. My neighbors know I’m a pilot, so I’ve been reduced to sneaking in and out of my building with my uniform in my bag and changing at the airport.

It’s difficult for the airlines to provide all the necessary precautions to protect “front-line” workers like me. I’m caught between the rational expectation that I should do everything I can to protect myself and my family, and the fact that I still need to go to work. The ground crew is cleaning the interiors more thoroughly and the airline is doling out alcohol towelettes for use in the cockpit, but it feels futile. Even before the epidemic, many pilots (including myself) would wipe parts of the cockpit upon first use, but what I’d need to do to truly sanitize a cockpit is impossible.

The way it works is that a flight crew will typically use a plane for at least half a day; sometimes, a whole day. Then another crew will pick up the plane, and it continues on its way. Aircraft keep moving almost continuously, but the crews swap in and out. The very nature of what we do in the cockpit involves touching things. We have the control yoke, gear lever, flap lever, hundreds of buttons, keyboards, touch screens, and more. And we touch almost all of them constantly: it is impossible to fly an airplane without touching anything, and it would be nearly impossible to truly sanitize every possible surface. Lately, when I pick up a plane, I’ll saturate my hands with Purell and then touch everything I can think of.

I maintain an amicable relationship with my ex-wife, who lives only a few blocks away. We share custody of our eleven- and thirteen-year-old children, who typically spend about half their time with me. But under these circumstances, they have not been to my place in weeks. The kids have been holed up at their mother’s, self-quarantined, practicing safe social distancing while I continue to go to work. Their mother and I have agreed that I will only see them in person out of doors and if we maintain a safe distance.

It’s painful, but things could be worse. Another pilot I know was told by his ex-wife that if she found out he went to work, she would revisit their parenting agreement and would consider taking him to court.

Advertisement

When I went to work last week, I never had more than a half-dozen passengers on each leg. I usually give a “welcome aboard” announcement over the PA, but lately we’ve often had only one or two passengers, so I’ve been introducing myself and the crew personally (from a safe distance). I thank them for their business, and try to make light of the terrible situation, telling them that today they were on their own private jet.

On Saturday, I felt lucky still to be working, but it was a “repo” flight, with no passengers or attendants, to reposition the aircraft and mothball it at a satellite airport until demand returns. As we taxied out of one of New York’s busiest international airports, I saw only one other aircraft moving on the ramp. Instead of the usual constant radio communication with air traffic control—normally, it’s hard to get a word in edge-wise—today it was nearly silent.

I hear about truckers being hailed as heroes for continuing to work in the face of adversity, but there is little mention of the men and women who are flying airplanes in an effort to keep this critical infrastructure in place: flight crews, especially at the major airlines, are carrying passengers and freight that includes vital medical supplies and essential health-care personnel around the country. I’m not disparaging truck-drivers; they’re essential front-line workers, too, but truckers, for the most part, sit alone, self-isolated in their cabs. There’s no social-distancing in a cockpit. Pilots sit right next to each other, inches apart in a confined space. And so it goes: face time with my co-pilot; FaceTime with my kids. ■

Nicole Rudick

April 4, 2020

SOUTH ORANGE, NEW JERSEY—I live each day in a house on a street in suburban New Jersey, about a forty-minute train ride from New York City, the view from the front door changing only by the tiny increments of budding spring (all about a month early owing to another cresting disaster). Aside from weekly trips to the grocery, we’ve hardly left our house in twenty-one days, and there is a sense not only of being shut away from the world but of being out of it altogether—or adjacent to it, somewhere terribly familiar yet not quite the same.

The girls down the street are riding their scooters, and the boys next door are running around and yelling. Here’s a family cycling by, and there’s a runner. Everyone’s doing their usual thing, but they’re not doing it together. They’re modeling life: this is what normality looks like. We’re in the uncanny suburbs of the town on Camazotz, from A Wrinkle in Time: “The children in our section never drop balls! They’re all perfectly trained. We haven’t had an Aberration for three years.”

Over text, my mother has been sharing her memories about the polio epidemic in the 1950s, when she was a child. She spent the summers in the doldrums of reclusion, in Akron, Ohio. It was boring, she told me. Pools were closed, and children were kept home. “As a kid, one doesn’t realize how bad it was, except there was the anxiety of having to be in an iron lung,” she says.

During the same epidemic, my father and his brother were sent to a day camp in upstate New York to get them out of Queens. Their father, a physician, rented a bungalow near the camp, and once, he was called on an emergency to a cabin. He took his medical bag and drove there in the rain with my father, who waited in the car. After a long time, his father returned, looking grim. He had diagnosed a camper my father’s age—eight or nine—with bulbar polio, the most damaging and debilitating form of the virus. Even after the intervening decades, my father can still recall how shaken his father was in that moment, not only by the diagnosis but by the fact that he had been exposed to the virus and so, therefore, had my father.

As the current virus first began to spread around the globe, I thought of “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain,” a story by James Tiptree Jr. from 1969. The biologist Dr. Ain flies around the world, making stops in Chicago, Glasgow, Oslo, Bonn, Moscow, Karachi, Hong Kong, Osaka, and Hawaii, all the while intentionally spreading a deadly virus meant to wipe out the human race. Ain unleashed his virus so that the sickened planet, whom he thinks of as his paramour, might live. “We are all wrong,” he says of humanity. “Now we’re over.” Such certitude, but the great die-out in the story happens off stage, almost banally, with the details left to the reader to imagine.

During this crisis, I’ve donated masks and food and money, I check on neighbors, and check in with friends and family around the country. The irony of this virus is that, for most of us, doing something to help means doing nothing. It requires staying away, staying apart. Simone Weil believed that we should “never react to an evil in such a way as to augment it.” In current parlance: stay home.

My mother suggests that my son, who is thirteen, keep a journal while he’s home and the virus rages. It’s a significant historical moment, she explains, and his daily reflections might be an account he’ll want to remember. But I think it would mostly be a record of his being trapped with his little sister every day and having ham for lunch again.

In the meantime, he is reading Art Spiegelman’s Maus for school, and in our conversation about the comic we’ve observed that death is arbitrary. Even in the case of the Holocaust, an organized mass murder, who lives and who dies on any given day is irrational. The randomness of it may be what is most terrifying.

This is what I think about, too, with regard to the virus: no one has earned living or dying. And sometimes participating in history is really boring, even if the moment in which you’re living is anything but. Sometimes boring is the best you can hope for. ■

Ali Bhutto

April 4, 2020

KARACHI, PAKISTAN—For the first time since the Nineties, when there were fewer people and less cars—and larger cumbersome vehicles—I am unable to hear the hum of traffic from my bedroom window. It has been replaced by silence. The curfew is enforced from 5 PM until 8 AM. But during the day, the streets of Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city, are far from empty.

The older part of town, on M.A. Jinnah Road, is eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns. Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

Law enforcement authorities occasionally stop commuters to ask where they are going. At various points, the street is divided into two lanes—one designated for regular traffic and the other for “healthcare services.”

As of April 3, there were 2,458 confirmed Covid-19 cases and thirty-five deaths reported across the country. But the official figures provide false comfort: thanks to limited access to health-care facilities, many cases will most likely remain undiagnosed and unrecorded.

Social distancing is a bit of an illusion in a country where there is no sense of personal space. There are exceptions. In a line outside a pharmacy on M.A. Jinnah Road, people are made to maintain a distance of three feet between each other. Others, however, huddle together. A veiled woman, begging for money, leans against the lowered window of my car.

In a supermarket in Clifton, an affluent neighborhood, people jostle each other. The cashier’s latex gloves are yellow at the tips. In an aisle, a salesperson without a mask brushes against me while walking past. Parking lots shared by supermarkets and banks are half-full. Bank employees in my neighborhood take a break outside, none of them wearing masks. In the quiet residential lanes, people emerge from gated compounds and go for walks—something they would never do under normal circumstances.

The domestic staff who work in some of the apartments in my building are on leave. But not everyone can afford to self-isolate. For some, starvation is a more immediate concern than the virus. The young man who sweeps the driveway of my apartment block comes every other day. With buses no longer operational, he commutes on a bike from his nearby home in the Postal and Telegraph Colony, one of the many slums located within the well-heeled neighborhoods.

At ten in the evening, I hear prayers being recited in the mosque and seminary behind my apartment block. The children living in the seminary chant after the prayer leader. Mosques across the country have, of late, initiated special prayers at night for protection against the present pandemic..

In February, before the arrival of the virus, a poisonous gas leak at the port killed fourteen people and led to the hospitalization of many more. The government agencies investigating the incident were unable to provide any explanation, and over time the entire episode faded from public discussion. In the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another. ■

Jamie Quatro

April 3, 2020

CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE—This morning, I raise the blinds on our third-floor windows and see snow: white flakes line the curbs and speckle the windshields and hoods of parked cars. But it’s April in Tennessee, and I look again, and the snowflakes are cherry blossoms whipped from branches by the wind on the backside of last night’s rain. The fact that I mistook spring for winter feels emblematic. Snow out of season wouldn’t surprise me. Very little would surprise me now.

Two weeks ago, the bars and restaurants were packed. On March 14, I took a photo of a sidewalk sign in front of the brewery on our block. The sign was a kind of flowchart: “Is Everything OK? Yes or No.” Both answers led to the same bottom line: “Come In and Have a Beer!” I texted the photo to a friend in quarantine in New York City. Here’s the problem with the red states, I wrote.

Things have changed—the bars and restaurants are now all carry-out, for one—but have they changed enough? Governor Bill Lee’s “Safer at Home” order went into effect Wednesday. It isn’t a mandated stay-at-home or shelter-in-place order. I’m not sure what it is. A list of recommendations citizens are strongly encouraged to follow. Lee said he chose not to issue a stronger order because “it remains deeply important to me to protect personal liberties.”

Personal liberties. The man who owns the Airbnb next door to us lives in Atlanta, so I was surprised to see him walking down our street last night. “Georgia’s governor just issued a shelter-in-place,” the man said, “so we figured we’d come up here to ride things out. At least we can walk to get take-out. Some friends of ours are going to come up later this week to stay with us, in case you see them around.” I’m half-angry and half-certain we would have done the same thing.

The couple at the end of our street work in health care. He is an internist, his wife a registered nurse. They’re young, early thirties, and had their first baby in November. The baby, born prematurely, was in the NICU for two weeks before coming home. Last week, I saw them out pushing a stroller and waved. From across the street, I watched as the father reached beneath a pile of blankets to pluck out the baby, lifting him high so I could see his chubby, wide-eyed pinkness.

From my upstairs window, I see another neighbor’s car pull into its parking spot in front of our townhouse. She is a nursing assistant who works the night shift. We often wave to each other in the mornings, when I’m just waking and she’s just getting home. How are things at the hospital, I asked a few days ago—me in my PJs letting the dog out, she in her scrubs.

Getting crazy, she said, walking toward her door. Just crazy.

It’s a beautiful day, sunny and cool. In the afternoon my daughter and I take the dog for a walk in Jefferson Park, children on bicycles veering wide as they approach. They know the drill. We make it a point to smile and wave to everyone we pass. It feels of supreme importance, at this moment in history, to be intentionally friendly in whatever ways we still can.

When we get home I find an email from Chattanooga Mayor Andy Berke, with the subject line “It’s Time to Shelter in Place.” It seems that Mayor Berke is ignoring Lee’s “advisory” and will sign an enforceable citywide shelter-in-place order, to go into effect on Saturday. An hour later, another email: Governor Lee changed course and has announced that he’s issuing a shelter-in-place for the state of Tennessee, effective immediately.

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders?

We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Still, I’m glad we’ll have some boundaries in place this weekend. Last Saturday, my teenage son and I rode our bikes to the Riverwalk park. We took a shortcut through the empty stadium parking lot, where a group of teenagers clustered around the open hatchback of a parked car. They were holding drinks and laughing, speakers whomping out a base line. Tailgating at the end of the world. It should have looked like fun. ■

Edward Stephens

April 3, 2020

ATHENS, GEORGIA—On my day off, my partner and I went to the grocery store. The shelves had been picked over, but at least the aisles weren’t crowded. I still found two bags of my brand of coffee and a nice spaghetti squash, our new comfort food.

The store had affixed glass windows to the checkout lanes as a protective measure for its clerks and customers. They are roughly two feet across by four feet high. “That’s nice,” I said, gesturing to the safety precaution. The woman checking us out was not satisfied, however. “Stand over there, where everyone stands while they wait to be rung up,” she said. I did. The glass barrier doesn’t go as far as the credit card machine, so that there was nothing between our faces. In all, three feet separated us, half the recommended social-distancing protocol. Shoppers usually stand at the pad for two or three minutes; longer now, probably, since they are buying so much more food.

She was right. The glass isn’t enough. Customers are still standing too close, and everyone is breathing on one another. I ran my card before she had scanned everything, which I never do, and took two steps back. She began to tell me I didn’t understand what it was like for her to work in such conditions right now. I interrupted her, because I do.

At the end of January, I started a new job—route sales and service for a snack food company. It was never the ideal thing for me, but it pays well and I hadn’t been close to keeping up with my bills at my old job. At thirty-four years old, with three school-aged daughters, it was past time I put my finances in order. I knew when I took the job that I had bargained away a little slice of my soul. It meant longer hours, leaving even less time for me to read and write.

What I did not count on at the time was that my health, too, might become part of the bargain. The fact is that the proportion of service to sales during my day is greater than nine to one. I spend fifty or more hours a week in the narrow but popular chip aisles of supermarkets, hemmed in by the company’s huge shipping carts and the slow browsing of the recently swelled eat-at-home population. I take measures, of course—gloves, frequent hand-washing breaks, a spray bottle of Lysol.

But there is no way around the fact that the essence of the job for anyone working in the crucial stores that are still open today is hazard. Even in Walmart, where, because it has suspended around-the-clock hours, it’s possible to work for nearly three hours each day before the customers press in on me, I find myself in close quarters with the small army of overnight employees—managers, stockers, proxy shoppers filling special oversized carts for online orders. For me, as for them, there is nowhere to go. I do not intend to stop working because I cannot afford to stop working.

My job takes me to a rural area north of Athens, Georgia, consisting of farmland and a booming truck-stop exit along I-85. I overhear a lot of skeptical conversations about the virus among Walmart’s employees and customers. Some of them are so innocent they break my heart; others, stridently dismissive, make my blood boil. Many of the people I encounter aren’t really worried yet. They don’t realize the virus is here already, even though official infection numbers are still low, that it has or will soon move from the truck-stop convenient stores to the surrounding towns, that somewhere it will take hold and bloom.

Another rural place, Dougherty County in southwest Georgia, containing no part of the Interstate Highway System and with a population of around ninety thousand, has nearly as many confirmed cases as (and more deaths than) Atlanta’s Fulton County, with a population of over a million. Officials have traced the contagion there to the February 29 funeral of a longtime local janitor. Ten days elapsed before one of the mourners, who was admitted to the hospital the night of the funeral when he complained of difficulty breathing, was confirmed to have tested positive for Covid-19. He had traveled 180 miles from Atlanta, where the virus was already beginning to spread widely. On March 12, he became Georgia’s first coronavirus death.

The mayor of Athens and county commission have been ahead of the state government and most of its municipalities in issuing shelter-in-place orders. That is a small relief for me as I set out for much less vigilant neighboring counties in the early hours each day to work in the only businesses that people are still patronizing en masse. I have no doubt that it’s only a matter of time before the virus reveals itself here, both in the city of Athens and the outlying towns. I know that I am not safe, and I am terrified. ■

Carl Elliott

April 2, 2020

AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND—Last week, on March 23, we awoke to an urgent message from the US consulate. The State Department was advising Americans in New Zealand to go back to the United States immediately or risk getting stranded abroad.

Should we stay or should we go? When my wife and I arrived on March 12, New Zealand had recorded only five Covid-19 cases, most of them mild, all of them involving travelers. To stay on was tempting. But our young adult children were still in the United States, and national borders seemed to be closing by the hour. So we began scrambling to exchange the lush, subtropical Eden of late summer in Auckland for the infected Minnesota winter.

I was in New Zealand to work on a book about whistleblowing in medical research. National Women’s Hospital in Auckland was the site of a cervical cancer study that New Zealanders call—with characteristic understatement—“the unfortunate experiment.” Women with a precursor of cervical cancer were left untreated for years. One of the whistleblowers at National Women’s, the cytologist Michael Churchouse, is now eighty-seven. Shortly after we arrived, on March 18, a friend and I had tea with him at his farm south of Auckland. At the age of sixty, Churchouse and his wife sailed around the world for nearly seven years in a thirty-foot wooden boat, escaping pirates in Asia and gunfire off the coast of Yemen. “It’s no wonder New Zealanders were the first to climb Everest,” my friend said. “They’re a bit of a mad lot.” Neither seemed nearly as worried about Covid-19 as I was.

But that conversation came before the epidemic began to escalate. When it did, the New Zealand government acted quickly. Recently arrived travelers were ordered into self-isolation. Airlines canceled flights. Restaurants were shuttered. A looming sense of menace hung in the air, as if anxiety had been aerosolized and sprayed into the pohutukawa trees. One day, my wife and I took a long hike out to Narrow Neck Beach and back to Tauranga/Mount Victoria. In a vine-covered cemetery, we found a gravestone that said, “Annie Turner Webb, who was called by her saviour to join his ransomed throng.” It sounded like Jesus was taking hostages.

The hidden threat of plagues is the way they turn your fellow human beings into objects of mutual fear. Every person becomes a potential vector of disease. Jacinda Ardern, the New Zealand prime minister, seemed to understand this instinctively. “What we need from you, is support one another. Go home tonight and check in on your neighbors,” she said in her address to the nation. “We will get through this together, but only if we stick together. Be strong and be kind.”

New Zealand is a small country that feels like a large village. It was the first place my wife and I lived after we married nearly thirty years ago, when I took up a postdoctoral fellowship in bioethics at the University of Otago, in Dunedin. When friends ask me why I keep returning to New Zealand, my response is always: “New Zealanders.” Kiwis are modest, outward-looking people who value tolerance, good humor and common sense. Their default self-presentation is one of cheerful unflappability. “She’ll be right,” they say. No worries. It will all work out.

We finally found a flight home, but it wasn’t easy. Australia had banned most foreigners from its airports, even passengers in transit to other countries, and most direct flights back to the US had been canceled. On the day of our departure, we packed up early and went to the car. Passersby smiled. A surprising number of bicyclists were on the street.

As we approached the Auckland airport, we saw an illuminated sign. It said: “Be kind. Stay calm.” ■

Liza Batkin

April 2, 2020

RHINEBECK, NEW YORK—After fourteen days of isolation in Brooklyn, I drove with my boyfriend to my parents’, upstate. I’m now self-sequestering in my brother’s old bedroom, not because I think I’m infected but because my dad is over seventy and it’s not worth the risk. This morning, I washed dishes with my mom sitting ten feet away and separated by a high counter.

“Can I use a dish towel to dry this, or should I use a paper one?” I asked her, along with whether I could pet our dog. I wondered whether to wipe down the Lysol wipes container with a wipe I’d pulled out of it. I searched for the spices, normally next to the stove, now moved out of sneezing range. The normal rhythms of drinking coffee and chopping onions and folding clothes are interrupted by second-guessing: If I just washed my hands, but then touched my shirt, should I wash them again before closing the cabinet? Our bodies, I realize, are relearning routines. Easy tasks take close consideration. I’ve lost my bearings in a kitchen I’ve known for twenty-six years.

A few weeks ago (which feel like years), my boyfriend showed me a video of the British comedian Steve Coogan in his Alan Partridge character, demonstrating how to “complete an ablution, entry to exit, without using your hands.” “Drop a thigh,” Patridge begins, bending his leg, then “elbow down to open,” as he clasps his hands and dips his right arm to the phantom door handle. He continues to narrate unusually graceful movements, popping his hip to open the door, spinning on left foot to face the “toilet,” lifting its seat with his right one, and so on.

“It’s funny to imagine getting so good at something so odd,” I think of saying, but stop myself from explaining the joke. It does seem impossible to ever adjust to the awkwardness of avoiding stray particles.

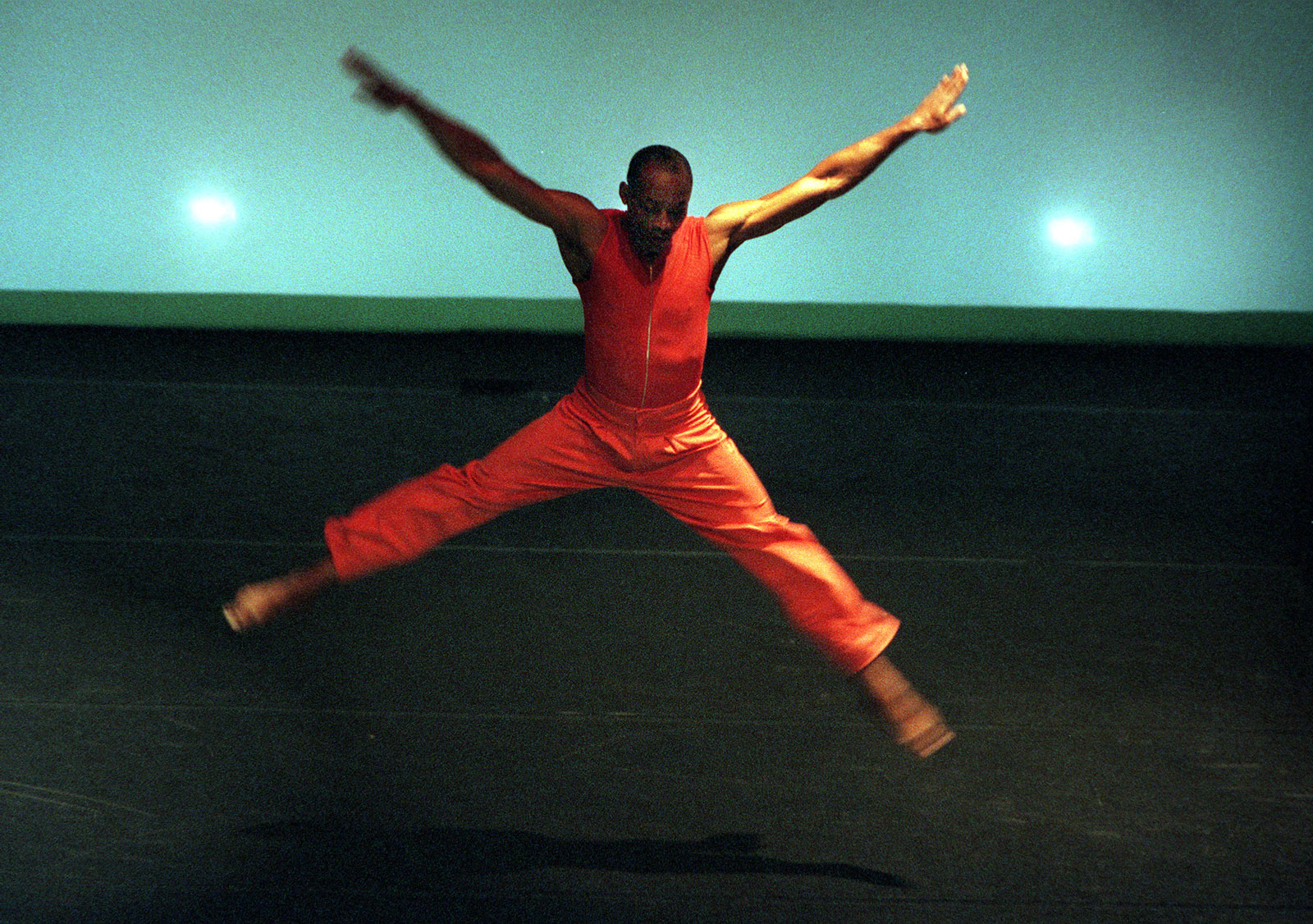

The routine reminds me of my favorite clip of the choreographer Bill T. Jones performing, initially, a short dance phrase, and then the same phrase while describing each movement in as much detail as possible. What was at first marvelously fluid becomes slower and belabored, though still beautiful, as Jones struggles to account for his body’s actions. “As one shifts one’s hip onto the left leg, the left arm breaks over the head, the right leg comes in and proceeds up to a passé parallel position,” he says, as his typically steady leg wobbles uncharacteristically. The task of carefully thinking about what he’s doing appears to unsettle his ability to do it.

Last Saturday, day seven of social-distancing, I tried to learn the choreography of Rosas danst Rosas (1983) by Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, whose West Side Story I won’t be seeing this spring. Her company made a tutorial available as part of a quarantine-inspired project called “Dance in Times of Isolation.” I’d first seen the piece in a year-long dance workshop in my junior year of college. Last week I watched a dancer teach it as I muddled through on my boyfriend’s couch, after finding that the chair—the choreography’s one prop—kept shifting on his nice wood floors.

The dance is full of impulse-like actions and slackened pauses. Sexy movements, like running hands through hair and crossing legs, are done with a staccato precision that nearly de-sexes them. I couldn’t learn the steps well or quickly, but I’m hoping by summer it will feel more natural and that the kitchen steps will no longer have to be. ■

Tim Flannery

April 1, 2020

BEROWRA CREEK, SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA—Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, 2020 was a terrible year for Australia, and in such dark times, humor helps us cope. The triple-whammy began with an apocalypse of smoke and fire. Megafires that created their own weather converged to become the most extensive conflagration ever recorded on any continent, destroying 20 percent of the nation’s forested land. They were finally extinguished in February—by deadly flooding. Then, as the floodwaters were still receding, the Covid-19 pandemic arrived.

I’m not a great reader of the Old Testament, but after our three plagues, I consulted Exodus on the nature of the fourth disaster inflicted on the ancient Egyptians. It was an outbreak of wild animals or flies. Australia’s wildlife being what it is, this fourth plague seems to me to be just a character of our country. So I’m now on the lookout for plague five: diseases of livestock.

Australia’s bushfire crisis was supercharged by climate change, and as chief councillor of Climate Council Australia, it had me working through the holidays. The floods, however, brought a different challenge.

I have a small holiday house on a creek near Sydney. It’s accessible only by boat, and my vessel was already within an inch of going under the floodwaters by the time I reached her. We bailed and bailed until I could get in and turn the key. When the outboard fired up, it felt like a miracle. Then, in conditions reminiscent of the storm in John Huston’s Key Largo, we took her the eleven miles to our house, dodging whole trees that were being carried by the flood.

Covid-19 began to stalk us. Our family had decided to retreat to the holiday house if things worsened, and we started to stock it with essential supplies. I’m glad I got onto the toilet-paper purchase early, for, in an early and strange response to the threat (though not one unique to Australians, apparently), Australians plunged into a toilet-paper buying mania that saw supermarkets stripped of this essential.

The great toilet-paper drought of 2020 was not Australia’s proudest moment: several shoppers were charged with affray after they fell to fighting over the last roll, and toilet-paper thieves have been caught red-handed by CCTV at some stores. Now there are rumors that “the good stuff” can be had, if the price is right, at certain online marketplaces.

Last week, my wife, two sons, and my elder son’s partner decided to retreat to our house on the river. Our first thought was to try to extend our food supply by fishing, but the flood had brought down so much food that the large specimens gambolling around our pontoon ignored our tastiest baits. But we needed a project to occupy us, and our minds turned to a long-deferred one: renovating an old, termite-riddled shed behind the house. With building supplies hard to come by, we decided to see what we could scrounge locally first.

An inspection of the nearby mangrove glades yielded, among other flotsam, a handsome picnic table and benches, much structural timber and planking, a sturdy staircase, a refrigerator in good condition, a tool rack, a forty-four gallon drum full of lubricating oil, and a trash can, miraculously delivered by the waters complete with lid and plastic liner. It was as if the flood had scoured a hardware store and delivered everything we needed at no cost.

As I write, all is well in our isolated retreat. The termites are banished, and we have enough building materials to recreate a habitable scale model of the Taj Mahal should we wish. We and many other Australians seem to be slipping into a new and more organic routine. I just hope that whatever the eventual outcome of the pandemic, we can all find some joy amid the constraints that Covid-19 has placed on us. ■

Ian Johnson

March 31, 2020

I spent the first five weeks of the coronavirus lockdown in Beijing, walking and walking and walking, as if by circumambulating the city I could open it up.

I wasn’t in one of the radically controlled parts of China, where residents became virtual prisoners, able to leave their apartment blocks or villages only with government permission. But friends quickly withdrew to the confines of family life, and their absence eliminated everything that made Beijing home.

I couldn’t keep from walking, and slipped out every day for hours at a time, like a widower mourning the sites of a past love. I regularly walked by the Forbidden City, where I had spent many hours with a friend who researched the immense palace’s geomancy. Usually bustling with tourists, it was now empty and locked tight toward outsiders, as it might have been before imperial China collapsed in 1911.

I entered some of the parks that were still open, such as Beihai. In the past, I had visited it with groups of friends who were believers in folk religion. Every Chinese New Year they would perform martial arts routines here, attracting huge crowds. But on New Year’s Eve this past January, the park was empty and on each visit it seemed sadder and sadder: the banners and flags welcoming the Year of the Rat were still up but the ice on the lake was slowly melting, as if humans had lost control of time.

Each visit was increasingly disorienting. I took pictures but didn’t post them on Chinese social media; it felt as if witnessing the city’s self-induced coma was unseemly.

One day, a friend broke ranks. He lived at the edge of the Western Mountains that mark the end of the basin around Beijing and the start of the Mongolian Foothills. He posted a picture of the old pilgrimage trail that led to Beijing’s holiest site, Miaofengshan—the Mountain of the Miraculous Peak, home to Our Lady of the Azure Clouds, or bixia yuanjun, a Daoist deity who blessed families with children and good health.

The photo was left uncommented upon, but it was clear there was a way to walk the old pilgrimage trail. I immediately booked a rental car and drove over the next day, but the entrance was locked. I turned to go, unsure if I should call my friend, when a guard came out of a hut.

“It’s closed due to the virus.”

“Don’t you remember me?” I said to him. “I made the pilgrimage to Miaofengshan last year by foot. I walked the whole way from the center of the city”—more than forty kilometers away. That part was true, although I didn’t actually recognize this guard.

“My gate is closed,” he said. “You cannot get in this way.”

I caught the hint.

“But other gates…”

“There are three other gates. They are all closed.”

“But a friend was on the trail yesterday.”

“Who can close a mountain?”

I bade him farewell and drove down a side road, stopping at a field before the next village. I could see broken corn husks but it was clear the land hadn’t been planted in years—typical for much of mountainous rural China, which the government was trying to reforest. But toward the back, as in every Chinese field, I still found a trail leading to the next field. It was overgrown but still passable, mainly because it was so rocky.

I ascended along a ridge, through brambles, past another abandoned terraced field, and finally my path joined the main pilgrimage route. An hour later, I was at the peak of this first hill, looking over a valley to Miaofengshan. The temple was tiny under the overcast sky, just a speck on the first of an endless string of ridges that ran to the horizon.

I turned and looked down at Beijing, low, gray, and quiet. Pious people believe that the goddess controls the fate of those down in the city, and maybe that was true. But whether the temple would open and the goddess worshipped—that depended on what went on down below me in China’s cities and towns. ■

From March 23–29: Sylvia Poggioli in Rome 🔊 • Jenny Uglow in Cumbria • Minae Mizumura in Tokyo 🔊 • Hari Kunzru in Brooklyn 🔊 • Rachael Bedard in Brooklyn • Lucy Jakub in Northampton 🔊 • Alma Guillermoprieto in Bogotá 🔊 • Nick Laird in Kerhonkson • Caitlin L. Chandler in Berlin • Yiyun Li in Princeton • Lucy McKeon in Brooklyn • Dominique Eddé in Beirut • Zoë Schlanger in Brooklyn • Ursula Lindsey in Amman • Nilanjana Roy in New Delhi • George Weld in Brooklyn • Richard Ford in East Boothbay • Eula Biss in Evanston • Martin Filler in Southampton • Ben Mauk in Penang • Michael S. Roth in Middletown • Sue Halpern in Ripton • Ivan Sršen in Zagreb • Tom Bachtell in Chicago • Adam Foulds in Toronto • E. Tammy Kim in Brooklyn • Keija Parssinen in Granville • Yasmine El Rashidi in Cairo • Merve Emre in Oxford • Tolu Ogunlesi in Lagos • Verlyn Klinkenborg in East Chatham • Rahmane Idrissa in Naimey • Aida Alami in Paris • Raquel Salas Rivera in San Juan • Michael Greenberg in Brooklyn

From March 17–22: Madeleine Schwartz in Brooklyn 🔊 • Anne Enright in Dublin 🔊 • Joshua Hunt in Busan 🔊 • Anna Badkhen in Lalibela • Lauren Groff in Gainesville 🔊 • Christopher Robbins in New York • Elisa Gabbert in Denver 🔊 • Ian Jack in London • Vanessa Barbara in São Paolo • Rachel Pearson in San Antonio • A.E. Stallings in Athens • Simon Callow in London 🔊 • Mark Gevisser in Cape Town 🔊 • Sarah Manguso in Los Angeles • Ruth Margalit in Tel Aviv 🔊 • Miguel-Anxo Murado in Madrid 🔊 • Tim Parks in Milan • Eduardo Halfon in Paris 🔊 • Anastasia Edel in Oakland 🔊