This is the current edition in a running series of dispatches by New York Review writers that is documenting the coronavirus outbreak with updates from around the world that began March 17–22 and has continued through March 23–29 and March 30–April 5.

—The Editors

Arthur Longworth in Monroe • Mira Kamdar in Videlles • Christopher Benfey in Amherst • Nathaniel Rich in New Orleans • Ariel Dorfman in Durham • Zoé Samudzi in Windhoek • Dalia Hatuqa in Amman • Hugh Eakin in Minneapolis–St. Paul • Verlyn Klinkenborg in East Chatham

Verlyn Klinkenborg

April 12, 2020

EAST CHATHAM, NEW YORK—Like a lot of people, I’ve been sewing face masks recently, for family and friends. I cut the pieces out of a couple of old cotton dress shirts, and I stitch them together on a sewing machine. Each mask is a little better than the one before it, the seams more even, the proportions more proportionate. I no longer have to replay a few seconds of a YouTube video to know what I’m supposed to do next. And as the construction becomes more effortless, I begin, more and more, to admire the sewing machine I’m working at. It is nearly as old as I am—a Husqvarna Viking 21a, made in Sweden around 1959.

A dozen years ago, when I first started sailing, it occurred to me that it might be useful to know how to repair a sail, or perhaps even make one. It turns out that cruising sailors—the kind who voyage about the world—have a lot to say about sewing machines. Their often strongly worded advice led me to some dependable, all-metal, vintage machines, most of them from the 1950s and early 1960s. They were going cheap on eBay—especially the ones described as “untested” or “as is” or “for parts only.” Soon, I was surrounded by an embarrassing number of them, including the one I’m using these days. I began taking them apart and repairing them, which usually involved little more than cleaning them and removing traces of old oil that had hardened into a kind of varnish. I sewed a new jib for a sixteen-foot dinghy called a Wayfarer, and then I put the machines into storage, where they wouldn’t humiliate me in front of company. Every now and then, I’ve managed to give one away.

The Husqvarna Viking 21a is a sleek, tubular machine the color of the 1950s—a pale, aqueous turquoise. I press the foot pedal and the electric motor begins to hum, and then the needle moves up and down. I know, from having taken it apart, how elaborate the inner workings of this machine are—belts, cogs, shafts, and gears shuttling round and round and back and forth in perfect synchrony. It is really a world of its own, a miniature factory. The internal light gleams down upon the arm, the feed dogs pull the cloth along, upper and lower threads intertwine in a stitch, and there is the harmonious sound of elaborate integration. At low speeds, the 21a sounds a little like a railroad engine moving slowly over the tracks. At higher speeds, it begins to whir. It does exactly what it was engineered to do, and it does it brilliantly.

My mother’s sewing machine was a Singer. I don’t think I ever knew the model number. But as my machine starts to stitch, I can hear hers stitching, too, across the years. I can see her seated at the dining room table in a small town in Iowa—about the time my machine was made—with the pattern for a girl’s dress pinned to the fabric. My mom sewed most of her own and my sister’s clothing, and she taught me how to sew when I was in high school. In my closet, there hangs a green corduroy shirt she made for me in 1969, a couple of years before she died. It was supposed to make me look like Steve Winwood in his Traffic days. It didn’t. I wore it only once or twice, but I’ve always kept it because it’s the only thing I have that was made by her.

Since the first of those vintage machines entered my life, I’ve watched a lot of sewing machine videos on YouTube. There’s a guy, a highly polished machine, a bench crowded with small tools, bobbins, gears, and lubricants. A pair of large hands comes into view, and they fold a piece of denim into eight layers. Then we watch as the machine—a Pfaff 130, for example—punches through the fabric. That’s about all the sewing there is. It’s a little sad that the guys in these videos—and I might well have been one of them—can’t ride their sewing machines down to the local drive-in on a warm summer’s night.

Advertisement

But to make face masks, I’ve been watching some actual sewing videos. And what I see are the articulate fingers of women, nimble and precise, working under the light of a modern, computerized machine. The cloth is adjusted with the smallest of motions. There are no surprises, only a methodical efficiency that comes from years of practice at actual sewing rather than sewing machine repair. This is how my mother’s fingers must have moved. I try to emulate them. I finish another mask and hold it up. It resembles the spinnaker on a tiny sailboat, and I almost forget why I made it. ■

Hugh Eakin

April 11, 2020

MINNEAPOLIS–ST. PAUL—One evening in late March, the state of Minnesota lurched briefly into the national consciousness: as Rachel Maddow described in her opening monologue on MSNBC, the governor, Tim Walz, had gone into self-quarantine. That same day, the state’s senior senator, former presidential candidate Amy Klobuchar, had disclosed that her husband was battling the virus, while the lieutenant governor’s brother, a “tough-as-nails” former marine, had succumbed to it. The number of infections was doubling every seventy-two hours.

“Just… one day in one US state,” Maddow intoned, with the deadpan astonishment she reserves for particularly alarming news.

In St. Paul, the state capital, however, it was hard to detect much disquiet. People were out in force with their dogs, kids, and friends; after a long winter, spring had finally arrived. In any case, the governor wasn’t asking anyone else to stay at home yet. (That recommendation would be made, very gently, four days later, but with few restrictions on activity in the out-of-doors.)

Situated in what Klobuchar likes to call “the heartland,” Minnesota has, in its own way, been at the heart of the American pandemic. In the suburbs of Minneapolis, across the river from St. Paul, several of the world’s leading suppliers of medical equipment, including 3M and Medtronic, are cranking out N95 masks and ventilators at a furious rate. In nearby Rochester, scientists at the Mayo Clinic, the state’s largest employer, are in a race to find a vaccine and to develop more efficient virus-testing technology. Yet few locals have started wearing masks and, throughout the state, testing for the virus has been notably limited. Days before his self-quarantine, the governor was still giving in-person briefings with the press.

Since the first cases here were diagnosed nearly five weeks ago, an obstinate equanimity has prevailed. Schools, universities, and most businesses have closed, lending to the recreation-obsessed metro area an air of perpetual Sunday. And so few seem to be staying home during what has been a particularly beautiful month. While wild turkeys, pileated woodpeckers, and even the occasional northern Goshawk have invaded the urban space, greenways and public parks have been teeming with people. Biking through town this week, I counted two different large groups playing volleyball; there was a sizable line at a popular ice-cream stand. This past weekend, as the number of verified Covid-19 cases in the state rapidly approached a thousand, friends of mine went kayaking.

Minnesotans—at least the ones I have met—tend to be a tough, outdoorsy, dog-owning, all-weather crowd, and the threat of a deadly virus has done little to change that. With offices shut, some city residents have escaped to lake cabins in the north, a favorite local tradition; others are taking advantage of the home-time to do lawn and garden work, causing unusual traffic jams at the neighborhood yard waste depot. (Nurseries and garden centers were added to the list of “essential” businesses this week.)

The governor, while expressing mild concern at the throngs that have been turning out along the Minneapolis lakes, has recently closed several city streets to traffic to serve the high demand from bikers and runners.

To almost any recent arrival, the Scandinavian sensibility is unmistakable: a can-do calmness; an aversion to controversy; a certain social reserve; an obsession with seasons and love of nature. But while the rugged individualism may have more in common with Norway than Sweden, the state’s unperturbed approach to the pandemic has sometimes felt closer to Stockholm than Oslo: if not quite to the degree of their controversial Swedish counterparts, Minnesota’s leaders seem to feel that people are intelligent enough to act responsibly, without the total lockdowns that have been imposed in Norway and elsewhere.

“We already self-isolate for four months of the year, so we know what to do,” a neighbor remarked this week, from a safe distance across the street. Despite evidence that the virus is spreading far more widely than official numbers suggest, and current projections showing a peak that is still weeks away, officials have already announced plans to allow some businesses to resume “normal operations” in the coming days.

Advertisement

But there is another similarity to Sweden, as well: social problems, such as they are, tend to get obscured. There have already been large-scale corporate furloughs and pay cuts, including for 20,000 employees at Mayo itself.

In vulnerable neighborhoods, auto thefts and robberies have spiked; on the depleted shelves of a discount supermarket this month, there was evidence of shoplifting for basic goods. Gun purchases have broken records.

Although St. Paul recently became a majority-minority city, there has also been little discussion about how the crisis is affecting the Twin Cities’ economically fragile communities of Hmong, Somali, Vietnamese, and other groups—including Native Americans, who make up a disproportionate share of Minneapolis’s large homeless population. And as in other parts of the country, members of the Asian-American community have reported rising hostility and racist attacks.

If the governor’s wager is correct, Minnesotans may yet emerge from the crisis in full vigor. Or we may find that our lakes, woods, parks, and river walks have become, through a kind of Bergman-esque transformation, as dangerous as the schools and offices we abandoned them for. ■

Dalia Hatuqa

April 11, 2020

AMMAN, JORDAN—It was late February when things seemed to change. I was going across the Allenby Bridge from Jordan to the West Bank, and as soon as I reached the Israeli side of the crossing, I noticed workers were wearing surgical masks. Passport control officers were asking visitors if they’d recently visited China. Everyone seemed on edge.

How on earth would this novel virus reach the West Bank, I thought. We were already living under Israeli military rule: under lock and key, surely we didn’t need to worry.

And we didn’t, at first. I saw friends, and we embraced with the kiss-on-each-cheek routine as usual. Ramallah was vibrant and alive. We ate and drank at busy restaurants late into the night. Every café and bar was bustling with people.

Even when, a few weeks later, seven Palestinians were diagnosed with Covid-19 after interacting with a group of tourists in Bethlehem, I didn’t think much of it. But within days, the seven became nineteen, Bethlehem was locked down, and a curfew was imposed throughout the area.

At the best of times, the West Bank is notorious for its creaking health infrastructure; preventive care is virtually unheard of. As a result, the ratio of providers and hospital beds to patients is inadequate. Many established physicians eventually emigrate, looking for a place to practice that’s not under military occupation; those who remain behind are often less experienced, or simply less competent. My own father was misdiagnosed by a Palestinian doctor two years ago. It was prostate cancer, but the doctor kept treating him for UTIs. By the time we took him to Amman, Jordan, and started chemo- and radiotherapy, it was too late. My dad passed away last July.

In March, as the number of those infected with Covid-19 in the West Bank grew, so did the rumors and conspiracy theories: the coronavirus was concocted by the Americans to bring China to its knees; the virus can somehow be fought by gargling water and salt ; and of course—because many people here are devoted to astrology—things should resolve after March 10 when the Mercury retrograde astrological cycle ends.

Not far away, Palestinians in the West Bank village of Taybeh—known for its brewery—were said to be spraying themselves with their local version of arak, the popular aniseed-flavored Middle Eastern alcoholic spirit, using the 104º-proof liquor as sanitizer.

Even at the height of the second Intifada, in 2002, Ramallah managed to keep some of its restaurants and cafés open. A friend and I would wait for the Israeli-imposed curfew to lift, a humanitarian window of sorts allowing us to go and replenish our grocery supplies, so we could make our way to a place called Sangria, our favorite watering hole. Then the owner would close the shutters and dim the lights, and under the glow of many candles, wine glasses in hand, we would toast each other as Israeli jeeps roared past outside, with soldiers yelling in Hebrew-accented Arabic “Mamnou’a altajawol!” or “curfew imposed!”

But today, Ramallah is a ghost town. The Palestinian Authority, which manages the West Bank, announced a month-long state of emergency, closing schools, nurseries, and universities. Public gatherings and protests were banned. Directives went out to PA employees to use email instead of paper for correspondence. Gyms and wedding halls were closed. Banks were instructed to operate for shorter hours; cemeteries even can operate only under new restrictions.

As Christian, Muslim, and Jewish holidays approached, Palestinians and Israelis alike mulled the celebration of Eid, Easter, or Passover, respectively, as indoor events, with only immediate family members. I also learned that the Hajj pilgrimage may be canceled this year; the last time this happened was two centuries ago. Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, too, closed its doors (for the first time since 2002); eventually, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher followed suit. If God had had to close his houses of worship, what hope did the rest of us have, I thought.

I left the West Bank for work before the border crossings closed, so now I am stuck in Amman, while my sixty-eight-year-old mother is left to fend for herself in Ramallah. The other day, she called me on Facebook Messenger, as she does every morning. I saw she had a bandage above her eyebrow: she’d fallen as she was vacuuming her bedroom, landing flat on her face.

A neighbor had helped clean up the cut; another was buying her groceries; a third paid her electric bill. It was a blessing that people were out to help each other. But that did not diminish the guilt I felt for leaving behind my mother at the height of a pandemic. ■

Zoé Samudzi

April 10, 2020

I flew out of Windhoek on Saturday March 21: the thirtieth anniversary of Namibia’s independence. As more than four hundred Namibian statesmen and foreign dignitaries (including heads of state who were discouraging their own citizens from international travel) assembled for the re-inauguration of incumbent president Hage Geingob, the government, encouraging social distancing, had officially forbidden public gatherings of more than fifty people in an attempt to curb the spread of the coronavirus. One press image showed Namibia’s founding president, Sam Nujoma, cheerily bumping elbows with Police Inspector General Sebastian Ndeitunga, as though that offset the health hazard posed by hundreds of people congregating.

While I had been obsessing over the latest epidemiological research, carefully tracking the number of new cases across Africa and within Namibia, where there are now sixteen confirmed cases, and slowly stockpiling sufficient food, many people in my neighborhood seemed not to share my urgency. For the time I was in Namibia, I stayed in a middle-class suburb named Kleine Kuppe, “small hilltop” in German.

From the balcony of my apartment, I could see Grove Mall, the popular shopping center where I bought my groceries. When I went in for food or the allergy medicine I needed, I saw people still trying on clothes, browsing luxury luggage and expensive cookware.

Going for what would be my last shop, after schools and museums had been closed and people were being encouraged to stay home, I asked the cashier if it had been busy, and how she was doing. She responded by asking where I lived: “The people who live around here aren’t bothered,” she said, “but people who live in ‘Tura are panicking.” ‘Tura referred to Katutura, the township in which most of Windhoek resides.

The social stratification in Windhoek stems from a bloody history, beginning with German colonial settlement in 1884 and the subsequent 1904–1908 genocide against the Herero and Nama peoples. What had been German South West Africa was eventually absorbed into apartheid South Africa before gaining independence in 1990 amid interrelated liberation struggles—called the Border Wars—in the settler colonies in Angola, Zambia, and what is now Namibia. The aforementioned Nujoma, a co-founder of the revolutionary party SWAPO, became the first president of the black majority-ruled Republic of Namibia.

It is no surprise that people’s abilities to respond to the pandemic would follow the same contours as apartheid. Much of the country’s wealth is still held by white people. As in South Africa, it seems that many black people in Namibia have only become poorer since independence. Anecdotally, the overwhelming majority of the people I saw preparing for isolation were white. Some of them were shopping as though they’d never cleaned their own homes before: one woman I saw at the checkout counter next to mine was purchasing nearly a dozen bottles of toilet cleaner, as though Covid-19 had the same exaggeratedly diarrheal effects as cholera or dysentery.

After the first two cases on record arrived in Namibia on March 14, via a pair of Romanian tourists, President Geingob announced the closure of schools and museums, social-distancing measures, and cancelled incoming and outgoing flights to Germany, Qatar, and Ethiopia (the latter two being major hubs for international travel from Europe and North American to the African continent) for thirty days. Social distancing and working from home are difficult to impossible for informal laborers living hand-to-mouth, as well as for the sizable population that lives in townships and for the essential workers who rely on the public taxi system of small, packed buses.

Thanks to the legacy of apartheid urban planning, the further north you live in Windhoek, the fewer resources you have access to and the less infrastructure and services become available. The Katutura township was created in 1961 when black residents of a neighborhood in southeastern Windhoek called Old Location were forcibly relocated about five miles away to the northern part of the city. In otjiHerero, “Katutura” means “the place where people do not want to live.” A sizable proportion—more than half, according to urban sociologist and University of Namibia professor Ellison Tjirera—of the city’s population lives in Katatura. Many are people who cannot afford to miss a day’s work or who cannot afford the now-inflated prices of medicines. Many live far too close to each other to socially distance, their domiciles may be too small to store multiple weeks’ worth of emergency supplies, and they may not have easy or dependable access to water.

After declaring a state of emergency, the government deployed the Namibian Police to help enforce lockdown. I worry now about the use of excessive force (especially against poor people), informal traders, unsheltered people, and others who out of necessity cannot comply with the new rules.

When I left, before the mandatory lockdown, Grove Mall shoppers did not seem particularly worried about the virus, perhaps because they believe the medical care they can access will protect them if they do fall ill. But, as the cashier said, many Katutura residents seem to understand how devastating it will be if the virus arrives, especially in the wake of the Hepatitis E outbreak in the city that has heavily affected townships and informal settlements. These are people for whom the government does not seem to have a plan. ■

Ariel Dorfman

April 10, 2020

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA—As in so many places across the world, the coronavirus has exacted a heavy toll on the people of Chile. It is not only the 6,501 cases of contagion and the sixty-five dead—expected to increase exponentially in the coming weeks and months—nor the havoc inflicted on an economy that was already sinking into recession.

When my wife, Angélica, and I left Santiago on the last day of February, after an almost three-month stay in our native land, the one collective concern was how intense the popular political mobilization would be in the upcoming month of March—whether the social revolt that had been gripping the country since October 2019 could be sustained, perhaps with even more fury than before. Citizens had protested in such colossal numbers that the rightist government of Sebastián Piñera had been forced to agree to a plebiscite that, on April 26, would define the contours of a new Constitution. And the demand for radical changes in salaries, pension plans, and the educational and health systems were expected to be unrelenting and extremely difficult for the besieged and inept president to contain.

The virus changed all that.

The plebiscite has been postponed till October, the streets that were thronged with fearless activists victoriously confronting the police are now empty (“First we have to stay alive,” is the explanation given by those most militant), and the government that, just a month ago, was held in utter contempt by a vast majority of Chileans must, in this moment of dire peril, be obeyed and relied upon to offer policies and guidance.

And yet, the class frictions and social inequities that initially provoked the revolt have only become more starkly evident: the rich in their privileged enclaves are offered more protection and care, while the less prosperous sectors of society receive second-hand treatment. Millions of Chileans live on the edge of an abyss, facing perilous conditions in the congested parts of many cities, as well as in the cramped public transportation they need to get to work. And their indignation grows when they see their more fortunate compatriots driving off to the beach to enjoy vacations, risking yet more contamination—although the government just ordered police checkpoints to stop such flagrant trips.

President Piñera has continued to be tone-deaf to the mood of the country. For the last six months, he dared not set foot near the iconic Plaza Italia that had been permanently occupied by protestors and renamed Plaza Dignidad. The other day, he used the fact that social distancing had forcibly freed that space of militants, to have a photo snapped there, as if to crow, “Look at me, I can now triumphantly loll around where just a short time ago agitators were demanding I resign.” Even so, he had to beat a hasty retreat when hundreds of residents of nearby buildings began banging pots and pans and shouting that he was a murderer.

Another faux pas came from the need, for health reasons, to reduce the occupants of Chile’s overcrowded jails. Piñera’s right-wing coalition tried to use the occasion to send home some of the elderly and infirm prisoners who had committed gross human rights violations—including extra-judicial executions, disappearances, and torture—during the Pinochet dictatorship (1973–1990). This attempt at undoing justice was met with a general uproar and is, for the moment, on hold. But it indicates how the wounds of the past keep festering, and how Chileans, even at a time of isolation and fear, will not cease to struggle for a more just country where nobody should be above the law.

Despite these and other abiding tensions, foreign observers have, on the whole, praised the government’s handling of the crisis. Opinions I have collected from friends and associates in Chile (all of them, admittedly, on the left side of the political spectrum) have responded with less generous assessments: Piñera acted tardily and only when usually supportive right-wing mayors joined the opposition to push him to take more drastic measures. My correspondents use such words to describe his conduct as “erratic,” “bumbling,” “favoring the powerful,” and even, from the youngest of them, “a blasphemy.” Word comes from another, as I write, that in its official statistics the government has included those who have perished from Covid-19 among the “recovered”—on the Orwellian grounds that the dead can no longer infect the living.

My own view—pieced together from our self-quarantine in North Carolina—is somewhat milder, perhaps because I do not need to endure the daily sensation that the dream of structural reforms was within reach and now may be slipping away. Or perhaps it is because I live in the United States, and compared with the anti-scientific, criminally neglectful, and confusing mismanagement of President Trump, the Chilean government seems to be acting with far more composure, efficiency, and appropriate concern. Chileans themselves also tend to be disciplined and responsible, as well as firm believers in solidarity in times of catastrophe (it is, after all, an earthquake-prone country).

I am only too aware, though, that there is much I cannot experience from afar, especially whatever may mitigate the dread, the pain, the loss that my compatriots there are suffering. The jokes that are, in fact, arriving in abundance display typical Chilean gallows humor. I am told that people back home are enjoying the pure air and blue skies as the pollution that habitually ravages our valleys has markedly diminished. They look in wonder as pumas descend from the mountains to the bare streets and condors that were all but extinct circle around high rises and drink from abandoned fountains.

Yes, there is much agony and frustration in Chile, but the country is also teeming with everyday acts of heroism and selflessness that whisper to me that the land I continue to recognize as my own seems to be very much alive in the midst of death and disease. ■

Nathaniel Rich

April 8, 2020

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA—The headline the other day on the front page of the Times–Picayune/New Orleans Advocate reads: “Orleans Parish Death Rate Highest in US—By Far.”

What I do with the newspaper: I remove the plastic wrap and place it in the outside trash can, careful to grip the lid of the can with the plastic that I am discarding. I carry the paper into the house and set it beside the stair, to begin its forty-eight-hour self-isolation. I approach the sink with hands raised, as if affirming a field goal, and give my hands the OR treatment. I’ve found it’s healthier—for the mind—and takes less time, to read the newspaper a few days late. In the pantry a row of boxes wait out their periods of self-isolation.

New Orleans has felt less like New Orleans. In disasters here usually the opposite is true: the storms bring people together, encouraging displays of fortitude, madness, resiliency. New Orleanians are trying—they are. There have been two-person second lines; front-porch trombone concerts; coordinated, appropriately distanced street dances. Chefs have converted restaurants to meal delivery services for hospital workers. Local distilleries produce hand-sanitizer. Face masks are being sewn by artists, dressmakers, and just about everyone else (New Orleanians have dedicated costume closets).

And yet… this is a city in which strangers feel like old friends. Now old friends are strangers. People don’t say hello in the street as often; more commonly they avert their eyes. It makes a New Orleanian feel guilty, the physical avoidance, the awkward detours—the performance of a sudden whim to investigate something of great interest across the street—required to avoid sharing a narrow sidewalk. It goes against the city’s nature.

Disasters, however, do not. Yes, New Orleans knows how to endure hurricanes, but it has also suffered a grotesquely disproportionate quantity of catastrophic fires and outbreaks—smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, malaria. In September 1918, a United Fruit Company’s steamer arrived from Colón with eleven soldiers infected with the Spanish Flu aboard. It was allowed to unload its bananas but none of its passengers were permitted to leave, save the sick soldiers, who entered an ambulance. On Tchoupitoulas Street, having just left the wharf, the ambulance crashed into a streetcar, tossing the sick patients onto the sidewalk with various streetcar passengers and passersby. The first New Orleanian died from the flu eight days later, a sixteen-year-old named Morris William Maurier. Two months after that, 350,000 Louisianans had been infected.

This new plague, as always with disasters, has laid bare the city’s monstrous inequalities. The death rate appeared, to a significant extent, to be a reflection of the city’s poor public health system, housing conditions, employment opportunities—or, to put it another way, the generational legacies of crudely institutionalized racism. About 95 percent of the early mortalities had underlying conditions. What percentage of New Orleanians have “underlying conditions”? Many have the foundational one: poverty. On Monday, after increasing pressure from local reporters, the state agreed to release the racial breakdown of deaths. In a state that is about two-thirds white, more than 70 percent of victims have been black.

The city has been united, at least, by outrage at the national perception that New Orleans failed to lock down the city fast enough, permitting Mardi Gras to go on. It’s probable that Mardi Gras doomed us to an early spread. But at the time, there were fifty-three cases in the nation, most traceable to international travel, and none in Louisiana. South Korea hadn’t yet announced its stay-at-home order and no major US events had been cancelled. As Jeff Asher, a local data analyst, pointed out, “There were 189 NBA games played between Feb 9 and Mar 11. At an average attendance of 17,750, that comes to about 3.3 million people going to an NBA game after the governors apparently should’ve known to shut down their economies.” Our governor, John Bel Edwards, and mayor, LaToya Cantrell, took aggressive action early; we are first in the nation in testing. The curve shows signs of flattening.

For three weeks, my wife and I have been preschool teachers. A week into isolation, my three-year-old said, “Dad, my body tells me that I’m sick.” He said his “neck hurt.” Horror bloomed like the jasmines and magnolias that sweeten the streets. My wife and I experienced shortness of breath, extreme fatigue, crushing headaches. A day later, our nine-month-old came down with a fever. He was sick three days. His pediatrician tested him for the virus. We had all felt fine for several days by the time we received a negative result. By then, we were disappointed: no antibodies.

When writing some years ago about a major gas leak in Los Angeles, I learned that psychiatrists who study environmental disasters have retired the terms “hysteria” and “psychosomatic.” They prefer “somatization” to describe the phenomenon by which people who falsely believe themselves to have been exposed suffer the same symptoms as those infected. Fear makes you sick.

We have little time to ourselves: it took me nearly three weeks to write these sentences. We fear for our isolated parents. We’ve washed our knuckles bloody. Just last week, our city led the nation in death. And we’re the lucky ones. ■

Christopher Benfey

April 7, 2020

AMHERST, MASSACHUSETTS—Two SUVs, dark green like the surrounding pines, were parked by the trailhead in the morning fog, marked “Massachusetts Environmental Police.” Two men in uniform, one of them wearing a protective mask, stood by the road talking. “Everything okay?” I asked. “A moose,” the taller man said. “Just hauled the carcass away. Your dog will smell it in a minute.” The shorter one said, through his mask, “Guess it didn’t get the memo on social distancing.”

The previous day, our governor, Charlie Baker, had issued the order to shelter in place. Had the moose felt safe on the suddenly quiet road, on the eastern edge of Amherst? Allie, our Australian Shepherd, indeed picked up the scent, just at the moment that I saw the thick red swoosh of blood crossing the no-passing line and extending thirty feet or more.

I felt some ritual was in order, some way to acknowledge the terrible thing that had happened here. I’d been reading the historian Bernard Bailyn’s The Barbarous Years, with its vivid chapters on the European invasion of New England during the seventeenth century. “Respectful of animals’ spirits, Penobscot hunters would not eat the first deer or moose they killed each season,” I read, while the Micmacs of Nova Scotia “refused to eat the embryos of moose for fear of their mothers’ retribution.”

The enterprising English colonists, by contrast, thought moose might make good draft animals, like oxen. Hitch a pair of them up to a plow, or drag some felled logs to the sawmill.

Instead of moose-powered, our own marauding vehicles run on fossil fuel, mercilessly laying waste our animals and our future. In Elizabeth Bishop’s great poem “The Moose,” a bus traveling south from the Maritimes to Boston encounters a moose, “grand, otherworldly,” in the road. The moose “approaches; it sniffs at the bus’s hot hood.” After this peaceful encounter “on the moonlit macadam,” the bus moves on, leaving behind “a dim / smell of moose, an acrid / smell of gasoline.” That’s our choice for the planet’s future: life for moose and other animals, like us, or death by gasoline.

“A Wounded deer leaps highest,” Emily Dickinson wrote. What about a wounded moose? This from the Encyclopedia Britannica: “In Siberia, hunters armed with muzzle-loading guns feared wounded moose far more than they feared the large brown bear. Due to the thick skin on its head and neck and its dense skull, an attacking moose could not be readily stopped with a small, round rifle ball of soft lead.” It could be readily stopped by a speeding car, though.

Dickinson lived two miles north of where the moose was killed. She must still hold the Amherst record for sheltering in place. “I must omit Boston” was a characteristic RSVP from the “Queen Recluse,” as a friend called her. “I do not cross my father’s ground to any house for town,” she explained.

Later in the poem about the wounded deer, Dickinson writes, “A cheek is always redder / Just where the hectic stings!” The hectic is tuberculosis, a disease greatly feared by the Dickinson family, who believed it was inherited. Her anxious father was convinced she had “consumption” as a baby, and yanked her out of Mount Holyoke for a month when she developed lung congestion and a bad cough. (Amid the global spread of similar symptoms, students were ordered to leave Mount Holyoke, where I teach, in March.) Doctors were consulted and medications prescribed. “Father is quite a hand to give medicine,” she wrote, “especially if it is not desirable to the patient.”

Dickinson thought that a different kind of infection was spread by slapdash writing. (A congressman’s daughter, what would she have made of our mendacious presidential briefings?) “A Word dropped careless on a Page / May stimulate an eye,” she wrote, but over the years, she believed, it could do lasting harm.

Infection in the sentence breeds

We may inhale Despair

At distances of Centuries

From the Malaria—

What other poet would risk rhyming despair with malaria? And are we not living in a time, right now, when we are in daily danger of inhaling despair along with mala aria—the bad air?

On our way back home, Allie and I passed the place where the moose was killed. The fog had lifted. The pine-green SUVs were gone. The scarlet blood remained until the next day, when it was washed away by a heavy rain. A rescue dog from Alabama, Allie is standoffish with other dogs. My wife and I joke that she has been practicing social distancing for a very long time. Emily Dickinson had a beloved dog, too, a Newfoundland named Carlo, whom she referred to as her “shaggy ally.” When Dickinson was asked why she avoided men and women, she replied, “they talk of Hallowed things, aloud—and embarrass my Dog.” ■

Mira Kamdar

April 6, 2020

VIDELLES, FRANCE—It’s been three weeks since I’ve seen my husband. It will be at least another week, more probably a month or more, before I see him again—if I ever do. A doctor working in Paris, he stubbornly continues to make house calls to elderly patients who depend on him, waiting an hour and a half in one man’s home for a special Covid-19 ambulance team to take him away. The man died a few days later.

The other day, my husband announced he’d volunteered to be on-call at three Paris hospitals treating coronavirus patients. “It’s my job, my vocation, and my duty,” he told me. That’s the kind of man I married. Damn.

Should he, a sixty-four-year-old heart patient himself, get the virus and require hospitalization, I would not be able to visit him. The thought of his dying alone and my never seeing him again haunts me day and night, even as I tell myself: No way could Covid-19 take him from me, he of the crinkly-eyed laughter and amorous hands, a side sleeper like myself, so French in his passion for soccer and good wine. No way.

Because of his job, we decided to stay apart when President Macron announced a national quarantine on March 16. His ninety-three-year-old mother lives alone in Paris and is entirely dependent on us. Should he get sick, we figured I could take over. So I collected my daughter and her boyfriend, temporarily cohabiting in her tiny, fifth-floor walkup studio, and drove us down to a house we bought last year in a village of six hundred people an hour south of Paris. My husband would join us on weekends. By the end of the first week, we understood that would not be possible.

At least I have my daughter with me. The rest of my family are scattered all over the world. There is no fleeing one blighted place for another, safer one, as my family did during World War II, leaving Burma for India. My father, an Indian immigrant to the United States, worked in aerospace. International jet travel was our way of commuting, and our standby escape plan.

Last week, for the first time since it opened in 1918, Orly Airport outside Paris closed. I worry about my son and his fiancée in Manhattan. I worry about my ex-husband, my children’s father, diagnosed with probable Covid-19 in Brooklyn. I worry about my elderly parents in Oregon and California. I worry about friends and family in India. Borders are closed, flights grounded. I am stuck here, they are stuck there.

There are no businesses in tiny Videlles. The post office, the elementary school, and the town hall are closed for the duration. Yet the roosters crow, the church bell sounds the hour, a dog barks somewhere, spring birds twitter in song. I cannot imagine empty streets and subway cars in Manhattan, where I lived for so many years. I cannot imagine Paris, the city that invented the restaurant, with its sidewalk cafes closed, rattan chairs stacked up, steel security curtains slammed shut. But here we are, quarantined in a little village in France without the French husband who is the reason I live here, in my adopted country.

The virus has thrown into stark relief the inequalities in France that sparked the recent Yellow Vest protests and the injustices long suffered in France’s poor, immigrant banlieues. In Pantin, the Paris banlieue where I usually live, many families are confined to small apartments. They cannot go out to a garden, as I do here, ripping out weeds until I am so tired that none of the worry can keep me tossing awake at night, and planting seeds to grow in a post-coronavirus world none of us can yet imagine. ■

Arthur Longworth

April 6, 2020

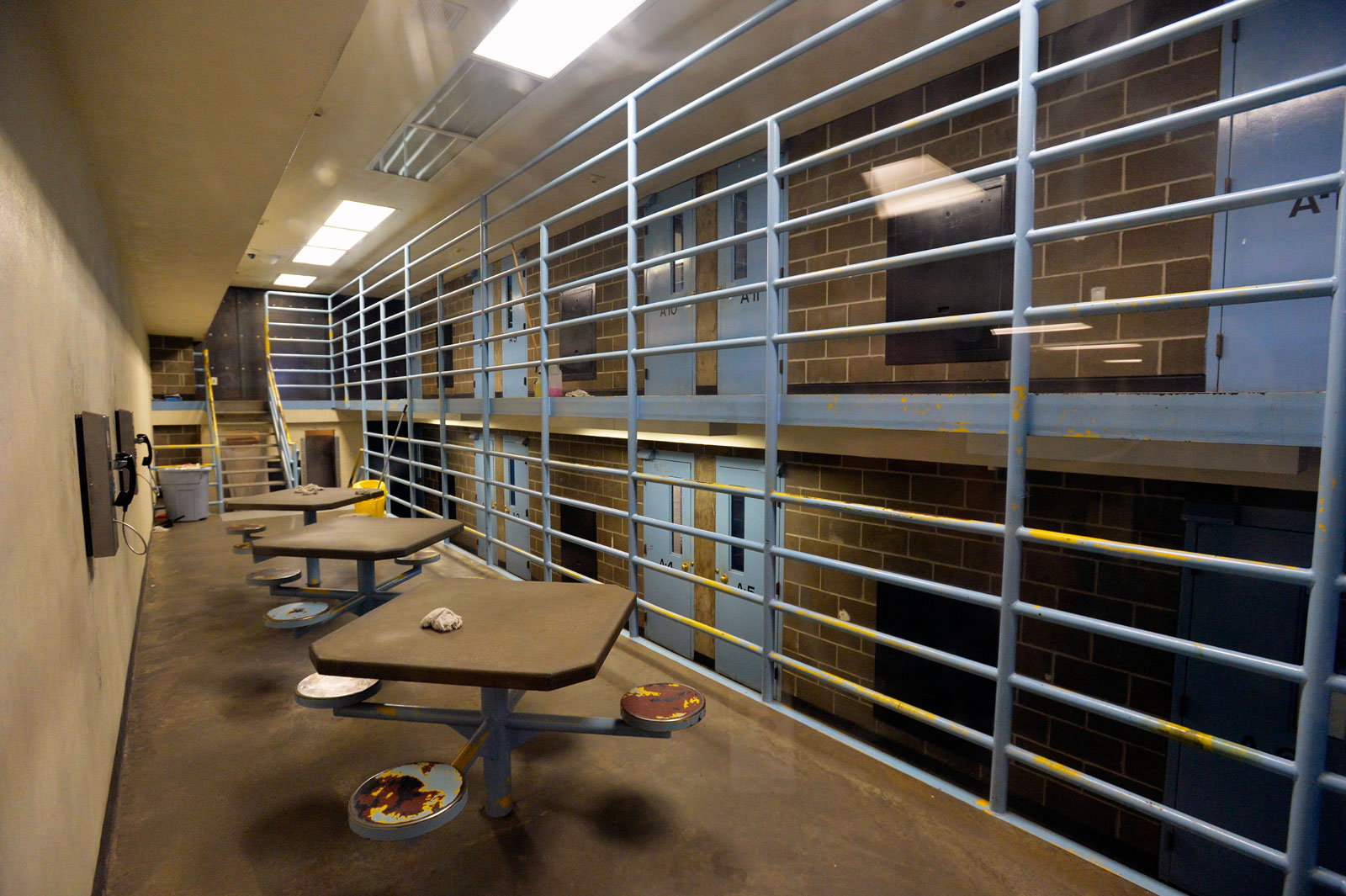

MONROE, WASHINGTON—The cellblock I live in looks like every movie you’ve ever seen about Alcatraz: a towering wall of a hundred and sixty barred cell-fronts, four tiers high and forty cells long. But the cells here are older than the ones at Alcatraz; Washington State built this prison one hundred and twelve years ago. And each of these six- by nine-foot cells are double-bunked—after all, this is the age of mass incarceration. The cellhouse comprises two of these cellblocks, three hundred and twenty cells in total.

The pulse of the prison passes through this cellhouse. I see it and hear it in a way that only someone halfway through their fourth decade of incarceration can.

“You guys are off lockdown.”

That was the announcement over the PA system on Monday March 23, at 9:32 AM, letting us know the quarantine was lifted. I knew—or at least hoped—the announcement was coming, because medical staff had ceased to make rounds and check our temperatures days earlier.

The cell doors racked open and we poured out of the cellhouse en masse— all of us who had spent the preceding two weeks confined in cells hardly big enough to turn around in, doing everything we could not to touch or brush against one another, not to breathe one another’s air.

We wandered out into a different prison to the one we knew two weeks prior, before a guard showed up to work infected with the coronavirus and got our cellhouse put on lockdown. Now, groups and organizations are no longer allowed to meet, and volunteers and sponsors (i.e., free people) aren’t allowed in the prison. All educational activities and courses are cancelled. Religious services are discontinued. And friends and family can’t visit, until further notice. Prison, even at its best, doesn’t feel tolerable—this unmitigated prison feels less so.

I can’t help but notice that a long line of prisoners still queues up in the morning at Gate 7. These are workers waiting to be processed through to their work stations in Correctional Industries. This doesn’t surprise me, nor should it surprise anyone. If the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement weren’t enough to abolish the kind of labor exploitation that still happens inside these walls, there isn’t any reason to believe a pandemic, or even an apocalypse, will.

On Tuesday March 24, in an attempt to implement the social distance protocol, prison administrators put a hundred-and-fifty-person limit on how many of us can go to the Yard. Which, of course, created a press of several hundred people in the courtyard shoving and fighting to get to the Yard gate. Those who made it had to place their hands—with whatever virus may be on them—on the bars of the turnstile in order to push through and get into the Yard. Everyone in the Yard shares eight phones that are situated eighteen inches apart.

On Wednesday March 25, in another attempt to social distance, guards directed us to sit one person to each four-person table in the chow hall. However, they still make us line up in close single-file order, forty to eighty prisoners at a time, to pick up a tray at the serving line window. And before we leave the chow hall, we close ranks again to drop off the trays and grimy plastic eating utensils at the dish pit where prisoners wash them by hand. The prison removed the dishwashing machine several years ago to save money.

On Thursday March 26, administrators reopened two antiquated cellblocks comprised of former disciplinary-segregation cells (also known as “the Hole”). They have sat vacant since our state built a $50 million long-term solitary confinement facility here nearly twenty years ago. An undercurrent of grumbling circulated through the population when guards moved parole violators into the cellblocks because local county jails—trying to bring down their populations in preparation for the onslaught of the virus—now refused to house them. All of us inside these walls know that if anyone is going to bring the virus in, it will likely be one of those prisoners plucked fresh off the streets.

Tonight, word spread through my cellblock—I heard the news pass from cell to cell, until finally it reached mine—that another guard and a prisoner had tested positive. ■

From March 30–April 5: Ian Johnson in Beijing and London • Tim Flannery in Sydney • Liza Batkin in Rhinebeck • Carl Elliott in Auckland • Edward Stephens in Athens • Jamie Quatro in Chattanooga • Ali Bhutto in Karachi • Nicole Rudick in South Orange • Andrew McGee in New York • Danny Lyon in Bernalillo

From March 23–29: Sylvia Poggioli in Rome 🔊 • Jenny Uglow in Cumbria • Minae Mizumura in Tokyo 🔊 • Hari Kunzru in Brooklyn 🔊 • Rachael Bedard in Brooklyn • Lucy Jakub in Northampton 🔊 • Alma Guillermoprieto in Bogotá 🔊 • Nick Laird in Kerhonkson • Caitlin L. Chandler in Berlin • Yiyun Li in Princeton • Lucy McKeon in Brooklyn • Dominique Eddé in Beirut • Zoë Schlanger in Brooklyn • Ursula Lindsey in Amman • Nilanjana Roy in New Delhi • George Weld in Brooklyn • Richard Ford in East Boothbay • Eula Biss in Evanston • Martin Filler in Southampton • Ben Mauk in Penang • Michael S. Roth in Middletown 🔊 • Sue Halpern in Ripton • Ivan Sršen in Zagreb • Tom Bachtell in Chicago • Adam Foulds in Toronto 🔊 • E. Tammy Kim in Brooklyn • Keija Parssinen in Granville • Yasmine El Rashidi in Cairo • Merve Emre in Oxford • Tolu Ogunlesi in Lagos • Verlyn Klinkenborg in East Chatham • Rahmane Idrissa in Naimey • Aida Alami in Paris • Raquel Salas Rivera in San Juan • Michael Greenberg in Brooklyn

From March 17–22: Madeleine Schwartz in Brooklyn 🔊 • Anne Enright in Dublin 🔊 • Joshua Hunt in Busan 🔊 • Anna Badkhen in Lalibela • Lauren Groff in Gainesville 🔊 • Christopher Robbins in New York • Elisa Gabbert in Denver 🔊 • Ian Jack in London • Vanessa Barbara in São Paolo • Rachel Pearson in San Antonio • A.E. Stallings in Athens • Simon Callow in London 🔊 • Mark Gevisser in Cape Town 🔊 • Sarah Manguso in Los Angeles • Ruth Margalit in Tel Aviv 🔊 • Miguel-Anxo Murado in Madrid 🔊 • Tim Parks in Milan • Eduardo Halfon in Paris 🔊 • Anastasia Edel in Oakland 🔊