At a moment when Britain appears to have retreated into dotty isolationism, at least with regard to the rest of Europe, the Met’s new British galleries situate almost seven hundred decorative objects from the collection within a relatively broad and inclusive historical framework. While the museum has had galleries dedicated to British decorative arts since 1910, this ambitious project, begun by curators Ellenor Alcorn and Luke Syson in 2014 and finished by Sarah Lawrence and Wolf Burchard after their arrival in early 2019, is intended to create a much larger, more immersive chronological experience. The three existing eighteenth-century period rooms from Kirtlington Park (Oxfordshire), Croome Court (Worcestershire), and Lansdowne House (London) are now surrounded by a reimagined suite of ten galleries dedicated to British decorative arts and sculpture beginning with the Tudors and ending with the Victorians, each one intelligently differentiated by the New York design firm of Roman and Williams in its first museum project.

Rather than encouraging the traditional old-school totter through the ancestral knickknacks of various respectfully referenced royal and aristocratic families, though, the curators ask us to consider the essential contributions of foreign artists and craftsmen—immigrants no less—to British artistic culture, figures often equipped with skills and ambitions unknown to the scrappy native workshops. And, further, to examine the objects in terms of the cultural appropriation and cross-pollination afforded by Britain’s expanding mercantile and global empire during this four-hundred-year period.

Britain was, in fact, something of a backwater when the sculptor Pietro Torrigiano arrived from Florence, probably around 1507, and some years before he made the bust of Bishop John Fisher (1510–1515) that presides over the entrance to the new galleries. Torrigiano was only one of numerous talented foreigners who courageously settled in the soggy islands over the course of the next centuries, filling artistic commissions for grand patrons and establishing individual reputations. Britain’s rapid development as the preeminent industrial economy by the end of the eighteenth century, when London became what is described here as a “collaborative scrum of talent, money, opportunity, and competition,” also ushered in a flourishing trade in tea, sugar, coffee, and cocoa from its various colonies.

As the installation of more than one hundred manufactured teapots in towering glass vitrines in a gallery dedicated to “Tea, Trade, and Empire” vividly demonstrates, tea and its accoutrements gradually became the focal point of social interaction in households of every kind. But Josiah Wedgwood’s famous antislavery medallion (circa 1787), showing a kneeling African slave in chains beneath the motto AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER, and Paul de Lamerie’s silver sugar box decorated with a scene of a native man harvesting sugar cane, remind us that the teatime rituals now all but synonymous with British gentility were underpinned by the exploitation of human beings, natural resources, and local industries. The Met’s approach, it should be noted, is consistent with a renewed interest among international scholars in investigating the landed elites and merchants who bought or built their country houses on the profits from slavery (see, for example, Slavery and the British Country House 2013, the published papers of a 2009 symposium).

If the interpretive materials only skim the surface of this subject, however, their spare, direct style also indicates that the new galleries are primarily designed to introduce British decorative arts to a general audience. And in this, they are largely successful, though the range of material is inevitably less broadly democratic than one would expect to see in a dedicated British design museum like the Victoria & Albert. Moreover, the Met’s holdings reflect, for the most part, the conservative and expensive tastes of the well-to-do Anglophone New Yorkers of the second half of the last century, whether donors or curators (although about a quarter of the works in the new galleries, especially for the nineteenth century, were acquired just for them). And while British irreverence and eccentricity are not really favored here either, the selections undeniably provide rewarding glimpses of it: in the eighteenth-century teapots shaped like camels, cabbages, and English houses; in the tiny feet on Christopher Dresser’s otherwise exquisitely austere silver decanter (1879) and spoon holder (circa 1878–1881); in Bruce Talbert’s monumental mishmash of a neo-Gothic cabinet (1866) featuring a scene and quotations from Shakespeare; and in the Martin Brothers’ grotesque bird jar (1888), with its swivel head and deeply unsettling expression.

Some things to look out for (a highly personal selection):

Torrigiano’s bust in polychrome terracotta of the bishop, a Catholic loyalist later beheaded, in 1535, for refusing to help the petulant Henry VIII divorce Catherine of Aragon, asserts the extraordinary level of artistic sophistication brought to Britain by foreigners during this period. Indeed, Torrigiano, a Florentine sculptor and painter, is thought to have introduced Italian Renaissance style to the Tudors. The subtle description and lifelike coloration of the bishop’s sober, sensitive features reflect Torrigiano’s early training in a circle of artists who studied with Bertoldo di Giovanni under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Michelangelo himself was part of the same circle; Vasari suggests that it was Torrigiano’s jealous assault against the young genius, permanently disfiguring his nose, that led Torrigiano to flee Florence in the first place. Under Henry VII and Henry VIII, he established a distinguished career creating similarly refined terracotta sculptures and tomb monuments.

Advertisement

The oak paneling made for merchant-trader William Crowe is among the most lavish of its kind. Ornately carved with flamboyant terminal figures, grimacing masks, and elaborate classical scrollwork, it reflects the emergence of a new class of moneyed consumer after the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558. English workshops began to respond to the commercial opportunities offered by expanded trade with Continental Europe and Asia in particular, and to the artistic and technical standards set by the increasing numbers of foreign artists and craftsmen arriving in England. The paneled room was shipped to America from Crowe’s house in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, between 1913 and 1916 and was acquired by the Met in 1965.

English interiors and furniture at this stage were mostly still somber and heavy. This English oak chair is nonetheless relatively slender and was evidently designed specifically for a female sitter; its splayed seat was intended to accommodate the voluminous layered skirts of the period while its narrow back and outwardly angled arms are based on a French model that came to be known as a caquetoire (from caqueter, meaning “to chat”), or conversation chair. It demonstrates how a foreign style might be adapted by an English maker to native woods and tastes.

The extraordinarily bold design of this tapestry—one of a set of fourteen commissioned by Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese wife of Charles II, as a gift to the Marquis de Fronteira in return for his loyal efforts to repel Spanish claims to the Portuguese throne—represents the high point of London’s role in the manufacture of complex, exuberant tapestries. And it suggests how radically British design and manufacture at the illustrious level had evolved from the gloomy parochialism of the previous century. While the designer is unknown, the production of this set, recounting the story of Don Quixote within a complex design of swirling grotesque ornament and woven in wool, silk, and threads wrapped in precious metal, was supervised by Francis Poyntz, the royal tapestry maker officially known as the “Yeoman Arrasworker of the Great Wardrobe.”

It is worth looking closely at the comic details here: Don Quixote aims his spear at the windmills as if they are actual enemies, a commentary on the arrogance and pomposity of the Spanish nobility. And many of the motifs appear curiously animated, from the ornamental elephant at the front of the vehicle on the left to the feathers of Don Quixote’s helmet that frame the eye of the donkey behind him, the cartoon-like serpent at the center, and the scrolling vine that creeps into every corner of the scene, sprouting not only flowers and tendrils but also the torso of a knight and the snake-haired head of a figure representing the winds, blowing apparently ineffectual puffs of air.

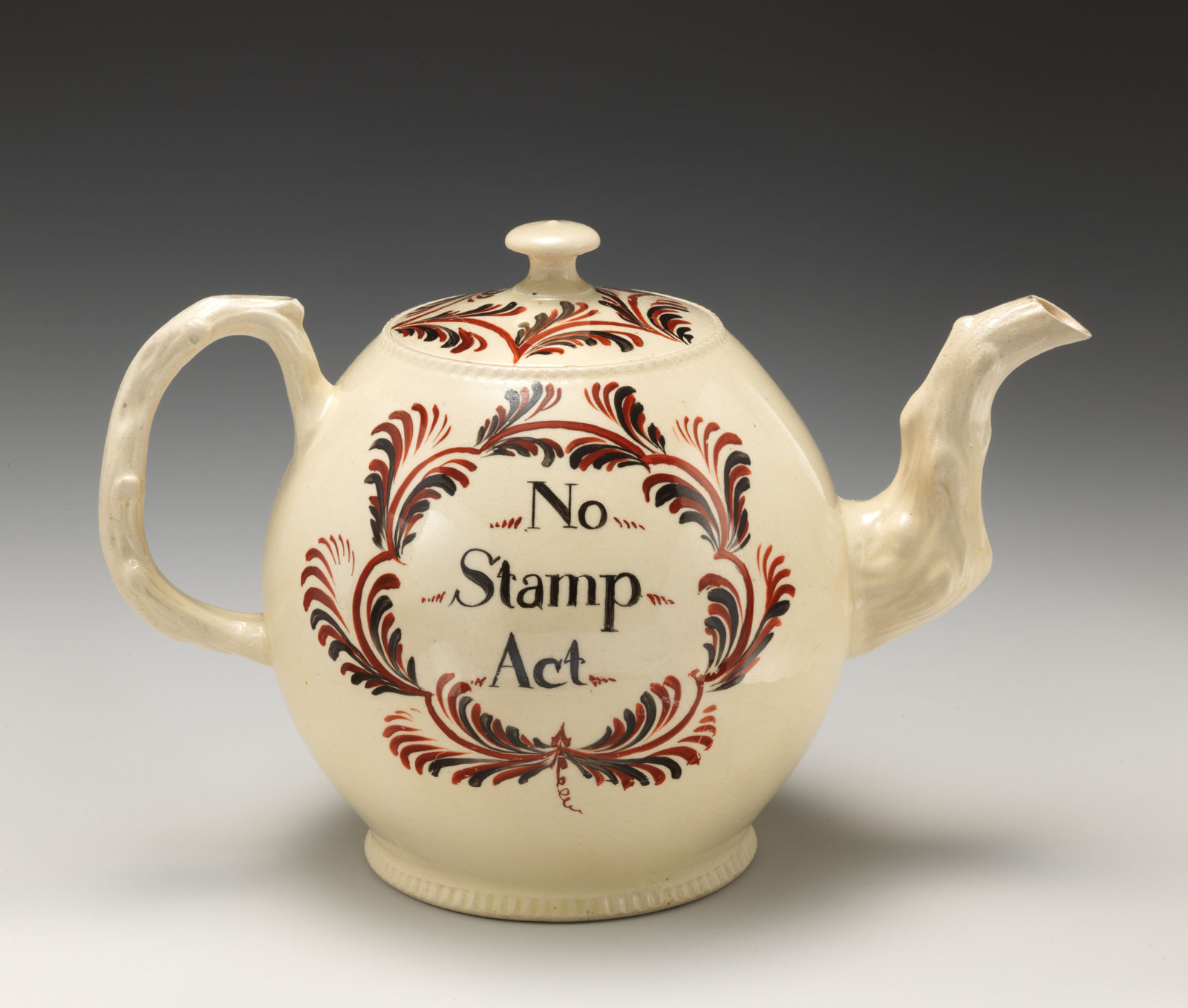

Never underestimate the power of the protest teapot. This version in creamware (an earthenware substitute for Chinese porcelain perfected by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1760s) bears two political legends: “No Stamp Act” on one side and “America Liberty Restord” [sic] on the other. It was one of many items marketed by the Staffordshire potteries to the American colonists after the 1766 repeal of the loathed British Stamp Act of 1765 that forced the colonists to pay a tax on all printed materials (we know how that ended). Like many of the teapots in the display, it is unmarked by the manufacturer’s name (potters before the entrepreneurial Wedgwood do not seem to have considered their products worthy of the distinction). A similar teapot, however, with the same crabstock (molded in the form of a gnarled crabapple branch) spout and handle in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is attributed to the Cockpit Hill Factory in Derby, England. The slightly off-center placing of the second message and the rudimentary style of the painted ornament in both teapots suggest rapid production, allowing the manufacturer to capitalize on the political moment.

Advertisement

While some of these manufacturers, like Wedgwood, were genuinely sympathetic to the colonists’ cause, others were, inevitably, simply cashing in. Like the English ceramic jelly molds emblazoned with the word “REFORM,” the teapot also suggests the ways in which women might use the tools of hospitality to indicate and even inspire a spirit of protest. Such an apparently homely vessel, strategically angled by the teacakes, might ignite all kinds of heated political debate: numerous abolitionist teapots for the English domestic market, for example, reflect the widespread female support for the antislavery cause (and the link between slavery and the sugar that was ubiquitous on British tea tables by the end of the eighteenth century). The British slave trade was abolished in 1807 and slavery itself was eradicated in most of the British colonies in 1833. Protest teapots might well be due for a timely revival.

This lead-glazed earthenware specimen reflects a trend among Staffordshire ceramic manufacturers, mainly in the 1750s and 1760s, for producing charmingly kitsch rococo-style teapots in the shapes of fruits and vegetables. These wacky designs pointed to an apparently insatiable consumer demand for novelty, and referenced both the English obsession with plants of all kinds and some of the exotic specimens that had arrived in England after the expansion of foreign trade in the late sixteenth century. Cauliflowers, pineapples, and melons were particularly popular until suddenly they were not; even Wedgwood made them, noting that he had exported a lot of what he called the “colley-flower” wares to the Dutch. Such frivolities were soon superseded in his factory by exceptionally inventive wares combining a refined classical style and technical innovation. This teapot is in the style of Thomas Whieldon, a successful English potter who partnered with Wedgwood in his factory between 1754 and 1759, chiefly to improve the lead glazes for creamware pieces like this. Like most of Whieldon’s output, it is unmarked.

This Staffordshire figure group in lead-glazed earthenware with enamel decoration, one of many nineteenth-century objects acquired especially for the new galleries, reflects the popular fascination of the period with the story of a British soldier named Hector Munro, who was mauled to death by a tiger near Calcutta in 1792. The incident, recounted by a captain in his party, was soon referenced in any number of British natural histories and cautionary tales for children; in an 1829 stage spectacle in London called The Tiger’s Victim; and, from about 1810, in Staffordshire figure groups similar to this one. Such groups were probably inspired more directly by “Tipu’s Tiger,” an almost lifesize wooden semi-automaton seized by the British army in 1799 from Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore. This contraption was later transferred to what became the Victoria & Albert Museum, where it continues to transfix visitors.

This plate, first produced in 1849, is an icon of the English Gothic Revival and one of Pugin’s best-known commercial designs. In this and his other most celebrated ventures—decorative designs for the new Houses of Parliament (from 1844) and the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition of 1851—he championed the Gothic style on moral, religious, and practical grounds. While the connection to bread is established by the stylized ears of wheat radiating from the central circular motif, a moralizing tone is set by the Gothic-inflected lettering around its perimeter: “waste not want not.” This injunction references the Hungry Forties, a decade of intense poverty and famine in Britain and mass starvation in Ireland created by potato blight, bad harvests, protectionist laws, exploitation, and economic depression.

The Minton factory produced a few ceramics like this one using the encaustic coloring technique widely practiced during the medieval period and more commonly used in the production of tiles. It involved inlaying colored clays into a recessed or stamped ground. This is the basic three-color version of the bread plate, but there was also a six-color variant and a version ornamented with opaque maiolica glazes. Pugin’s views on the integrity of the Gothic craftsmanship of the Middle Ages, one that contrasted conspicuously with what he saw as the soulless regularity of classical architecture and the inchoate vulgarity of much Victorian industrial design, had a significant influence on the work of such successors as William Morris and Christopher Dresser; the injunction on his famous bread plate seems to have had far less impact in the first industrial nation and its empire.

The new British Galleries, now closed temporarily due to the Covid-19 pandemic, opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on March 2.