Incarceration has reshaped my family and my hometown in southwest Ohio. Countless relatives have been arrested and detained; some have been convicted and sentenced, while others have been held indefinitely and then let go. One cousin was held in a county jail for several months without any charges ever being filed. Some of us have been profiled by police and falsely accused of crimes. Others have been convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to long periods in prison. The same month that I graduated from college, two of my closest cousins were convicted and sentenced for involvement in the death of another young man from our community. There has never been a time in my life when prison didn’t hover as a real and present threat over us.

I originally started working on Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration—a survey and analysis of visual art and creative practices among incarcerated artists, as well as art that responds to mass incarceration, which accompanies an exhibition that was scheduled to open at MoMA PS1 on April 5, but has been delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic—as a way to deal with the grief about so many of my relatives, neighbors, and childhood friends who were spending years, decades, or life sentences in prison. It was also an effort to connect with others who are separated from their loved ones by prisons, parole, policed streets, and other forms of institutional and quotidian violence.

My family lived in a mill town that had experienced the woes of factories closing. The unionized manufacturing positions that had sustained our working-class and lower-middle-class black community for a couple of generations were no longer available. Studies of mass incarceration and the carceral state offer insightful explanations and historical accounts of what many of us witnessed and experienced in our communities: the mass removal of family members, neighbors, and friends, along with the permanent stigma on imprisoned people and their families.

As I came of age, in the 1980s and early 1990s, people around me, mainly young black men but also older women and men, were being shipped off to prison at such a frequency that their sudden disappearance and long-term absence became the norm. Boys my age who went to elementary and junior high school with my cousins and me were there and then gone, some never to return. They became invisible to us and hard to reach because of all the mechanisms the carceral state uses to separate imprisoned people from their families and communities. We had no words to describe the utter devastation, the despair.

Investigations of prisons from historical, legal, economic, and many other perspectives have analyzed the range of causes and implications of the rise in prison populations. Attacks on the radical movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the War on Drugs, adverse consequences of the War on Poverty, the War on Terror, deindustrialization, neoliberal policies, law-and-order policing, segregated and punitive education, unemployment, the criminalization of poverty, austerity measures, and longstanding discrimination against nonwhite, queer, and gender-nonconforming people—all contributed to an increase in the US prison population of more than 500 percent since the 1970s. This confluence of circumstances has resulted in the United States’ having the highest rate of incarceration in the world, with almost 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 1,852 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, and eighty Indian Country jails, as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, and state psychiatric hospitals.

In popular entertainment, journalism, and documentaries, images of “life behind bars” fascinate, horrify, and titillate. They also offer a familiarity with prison as a cornerstone institution of modern life, but one that the majority of people never enter. The nonincarcerated public comes to recognize prison and the people in prison almost exclusively through a set of rehearsed images created by the state and by nonincarcerated image-makers—images like arrest photos, mug shots, the minimal furnishings of the prison cell, fortress-like walls, barbed wire, bars, metal doors, and the executioner’s chair. About this familiarity with the visual representation of prisons, Angela Davis writes:

The prison is one of the most important features of our image environment. This has caused us to take the existence of prisons for granted. The prison has become a key ingredient of our common sense. It is there, all around us.

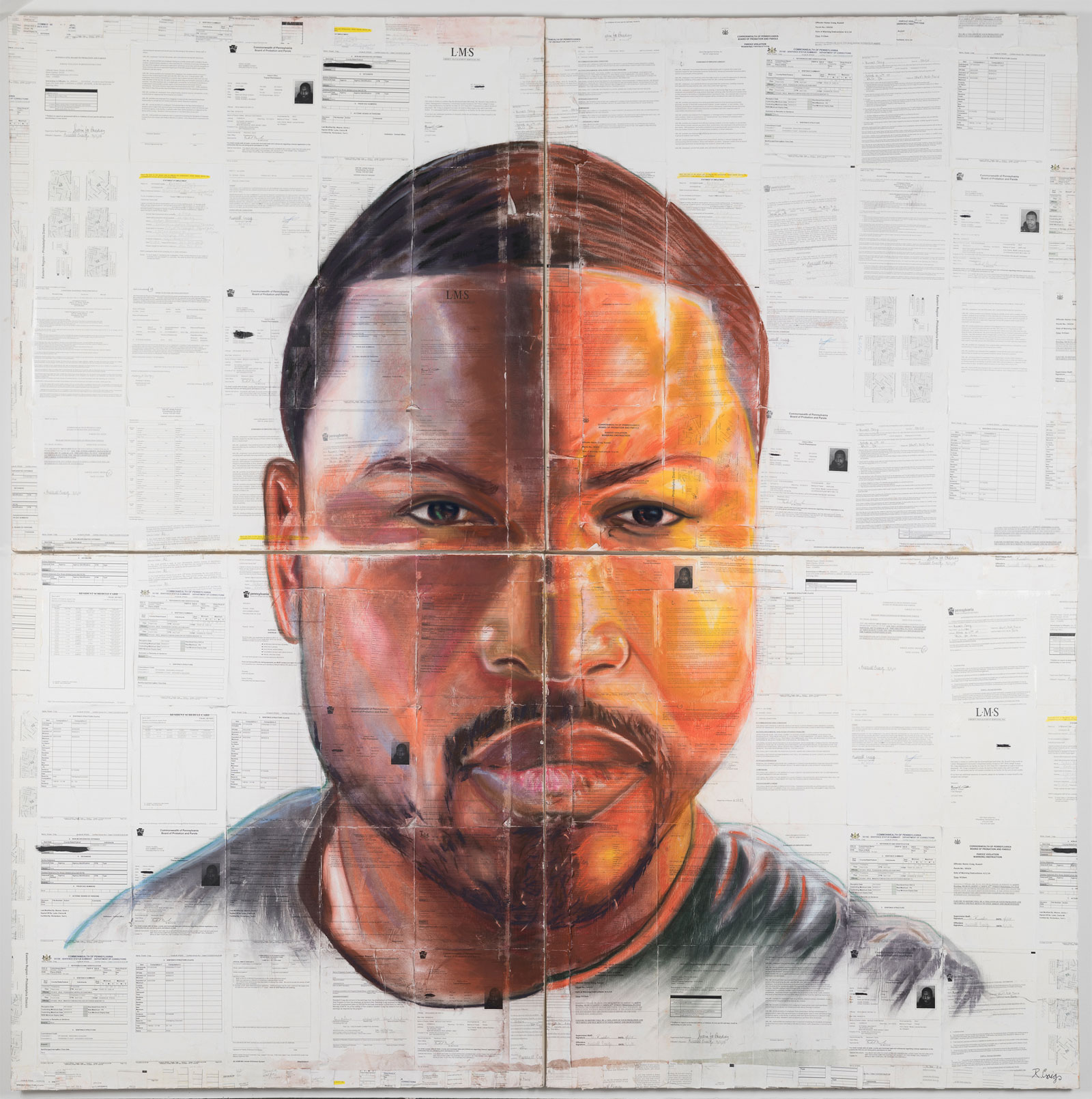

As prisons made more and more people invisible in the communities they came from, images were employed in communities like mine to justify mass incarceration. Pictorial representation was an essential tool used to support tough crime policies and punitive sentencing. Hostile and dehumanizing images, such as “wanted” posters, arrest photographs, crime-scene images, and mug shots circulated constantly in local and national media, and reinforced the practices of aggressive policing and dominant notions of black criminality. Stories circulated of the rampant devastation of the crack era, portraying young street dealers as monsters.

Advertisement

Opening our local newspaper was often cause for pain and embarrassment, as photographs of people we knew seen in handcuffs were all too common. Often, these were images of black children and teenagers, infamously referred to as “superpredators” in the 1990s by journalists and politicians, most notably Hilary Clinton. One of the best-known, most egregious examples was the portrayal of the so-called Central Park Five, now known as the Exonerated Five—five black and Latino teenage boys who were falsely accused and convicted of raping a white woman—as “a wolf pack.”

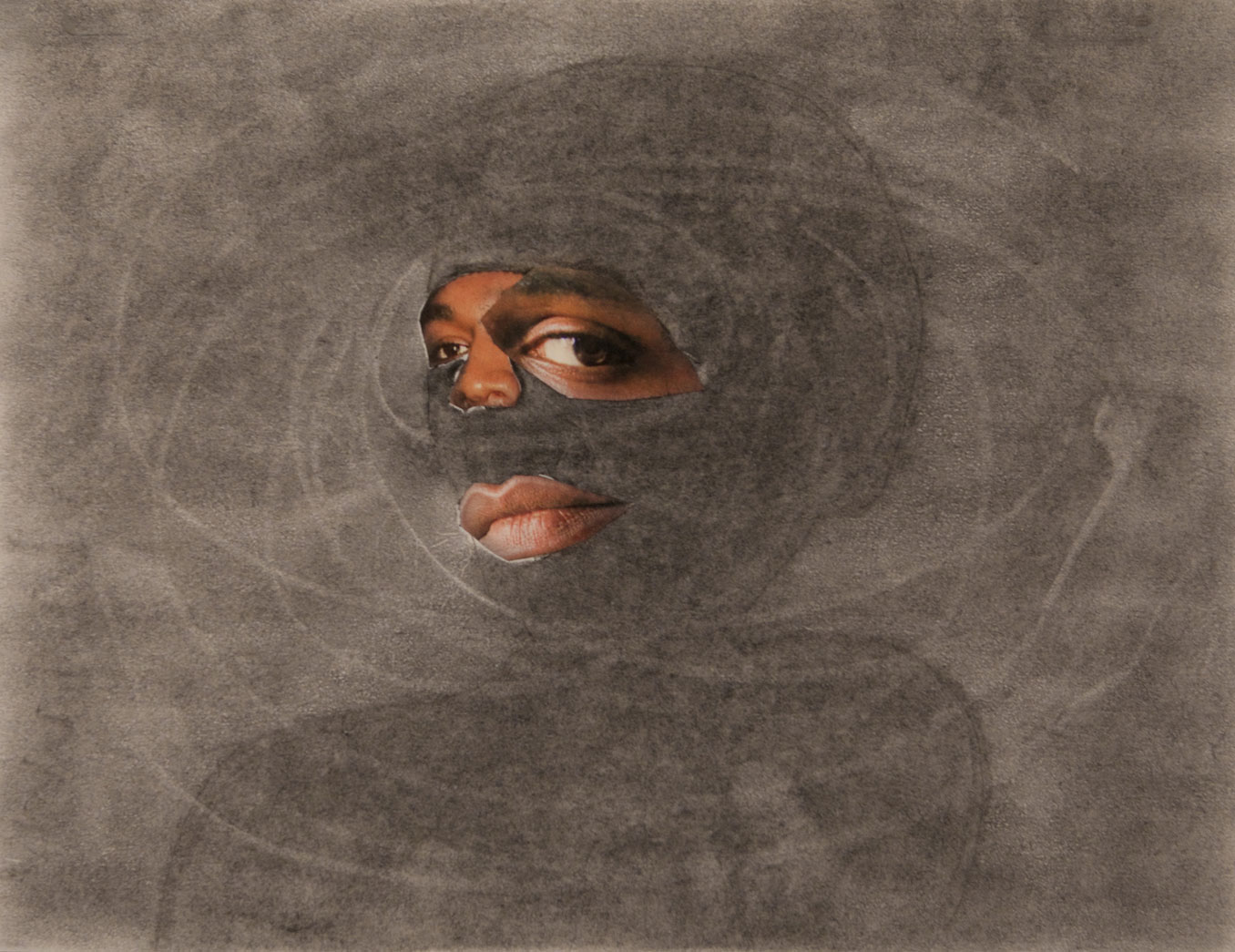

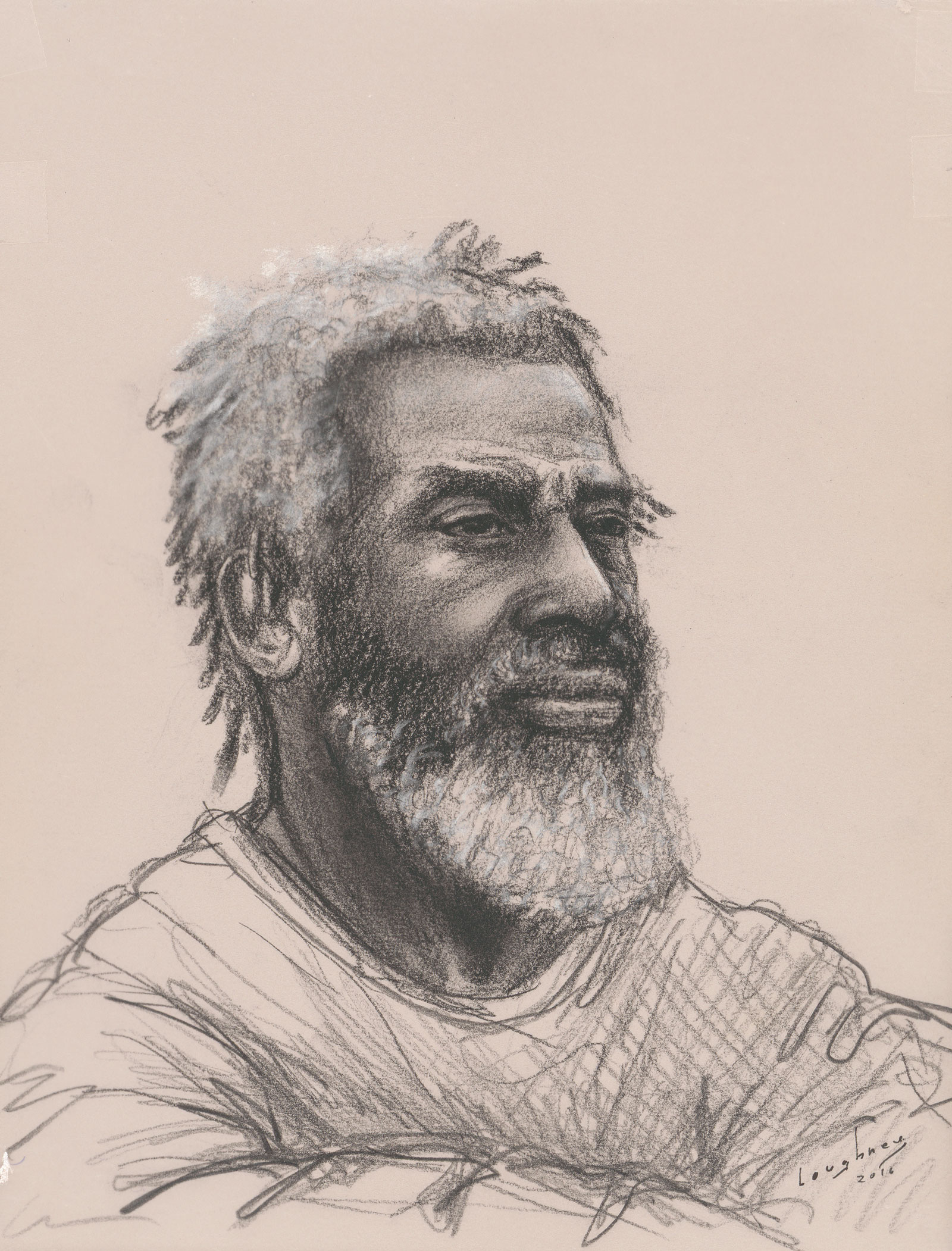

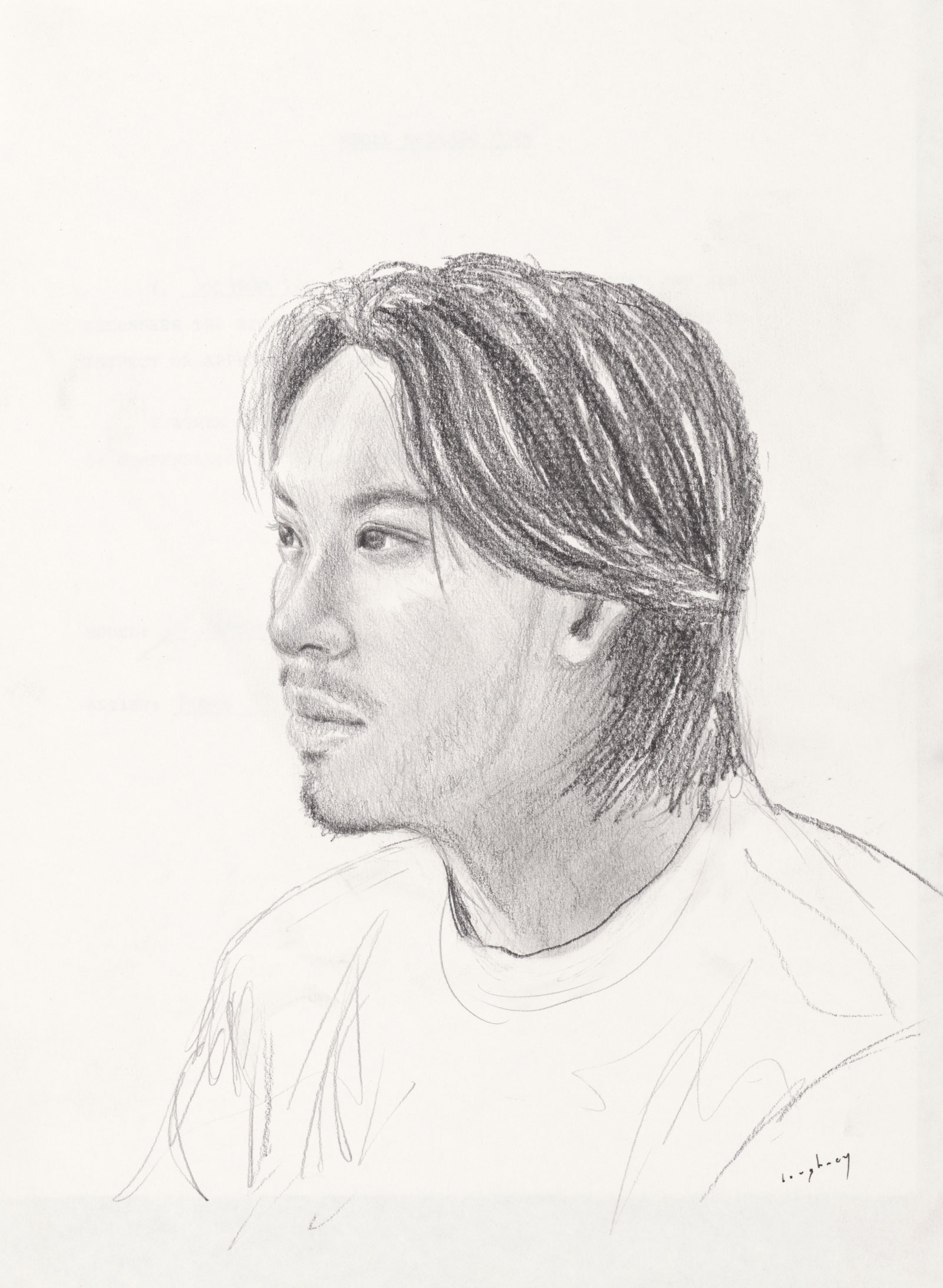

At the same time, there were other images being produced about mass incarceration—images that rarely made the news and had little or no public circulation. They offered different stories about and interpretations of prisons and their impact. These were not journalistic, scholarly, or legal documents. They were a diverse assortment of artworks and illustrations that came from inside the prisons themselves: studio photos, handmade greeting cards, drawings, and other pieces of art made by incarcerated people.

Incarcerated relatives sent home graphite drawings and birthday cards designed by artists in prison. Some prisons permitted us to take photographs together when we visited our relatives and friends. The visiting rooms where we sat with our imprisoned relatives and friends often displayed paintings, miniatures, and sculptures made by incarcerated people. These objects were not new forms of prison art, but as the size of the prison population boomed, the visual culture of mass incarceration grew along with it.

I began what would become Marking Time by displaying photos of incarcerated relatives around my apartment, partly as an attempt to work through my own discomfort with the pictures of them in prison, and to bring their presence into my daily life. At first, I was afraid that it would be too emotionally challenging for my family and me if I focused on a project about incarceration and the visual. But after a first presentation at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey in 2012—at which I spoke about my incarcerated relatives and the visual records of their incarceration: family photos, cards, drawings, and paintings on bedsheets—something unexpected happened, something that would continue to happen over the years of lecturing and doing research on prison art.

People came up to me afterward to describe how they were directly impacted by prisons, how they had been incarcerated themselves or had loved ones in prison. They described the shame and emotional difficulty of talking about these experiences in public. Some shared photos and art that came from prison. This is how the project grew—by word of mouth and by connecting with others. I began to build community around our collective pain and survival, the many millions of families affected by incarceration, the many millions held captive by prisons and other carceral institutions. Under the grief and rage was a sense of solidarity with others who shared the experience of watching their communities devastated by the various tentacles of what we call mass incarceration, the impact of which goes far beyond prisons.

Marking Time grew out of nine years of researching and archiving, and draws on multiple sources: interviews, site visits, personal collections, institutional archives, family narratives, and the growing scholarship in critical prison studies, black cultural theory, and visual culture. I have traveled to several states to meet formerly and currently incarcerated artists. I have interviewed more than seventy people, including imprisoned artists, teachers, nonprofit administrators, prison staff, activists, and the loved ones and relatives of imprisoned people.

Marking Time is about both the centrality of prisons in contemporary art and culture and the robust world of art-making inside US prisons. I set out to engage the politics of this art-making in prisons, and, more expansively, art as politics in an era of extensive human caging and under other forms of carceral power. How has the colossal reach of the prison industrial complex shaped contemporary art institutions and art-making? And how does visual art help to reveal the depth of devastation caused by our nation’s punishment system?

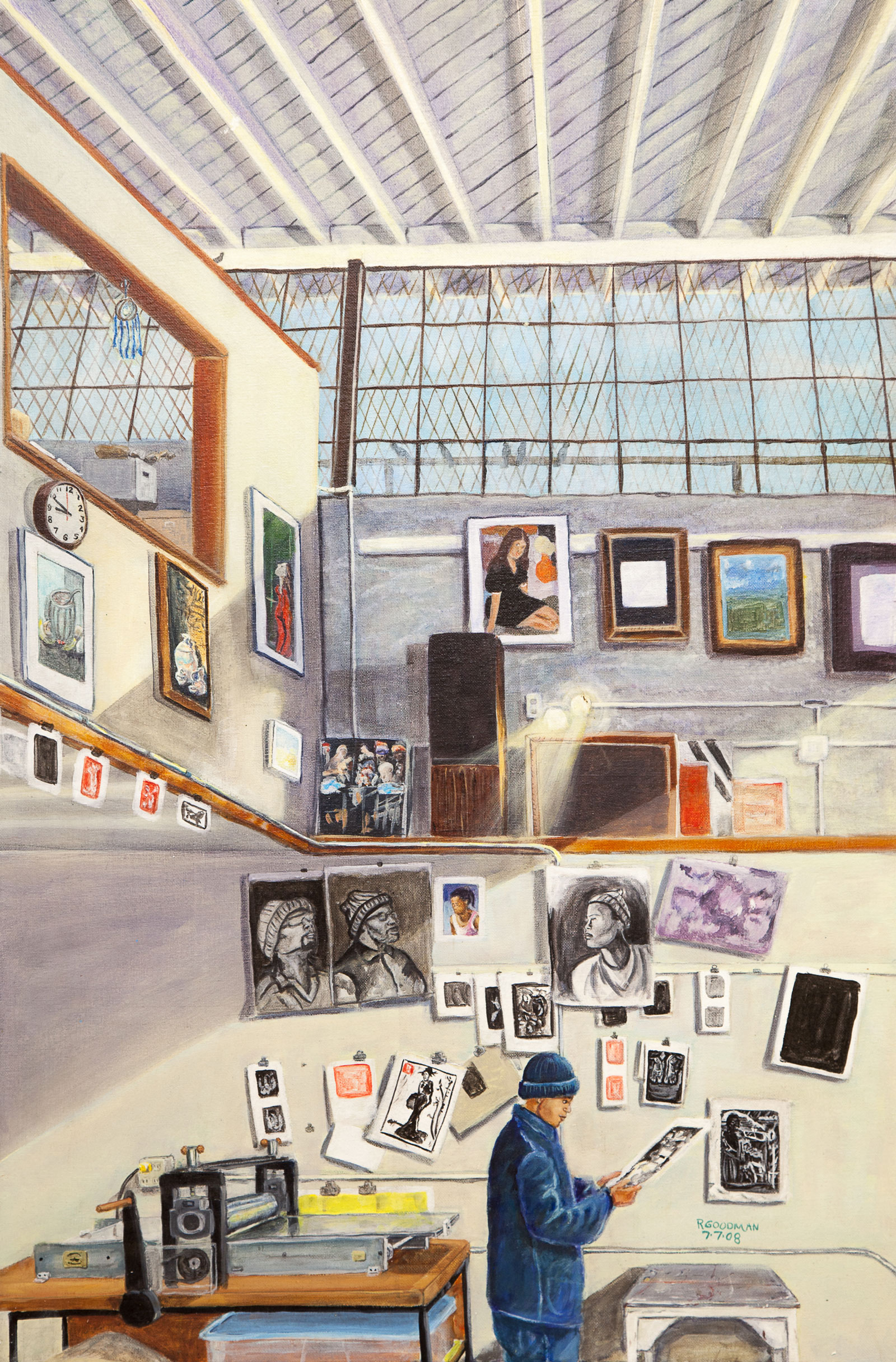

In Ronnie Goodman’s 2008 painting San Quentin Arts in Corrections Art Studio, the artist is alone at work in a studio. The self-portrait shows him inside a cavernous space of multistoried walls and beamed ceilings. We see him in profile, from the knees up, dressed all in blue and bent slightly forward, studying a print. On the walls, dwarfing him and above his reach, are portraits, landscape paintings, and still-life renditions. The details of the workspace—the light, the height, and the open floor plan—all suggest an idyllic scene for the creation of art. Indeed, Goodman’s painting references and inserts itself into a long tradition of documenting the artist at work in a studio, art class, museum, or other institutional setting, such as Samuel Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre (1831–1833) and Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Studio) (2014).

Advertisement

Goodman made the painting while he was incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison and a participant in the Arts in Corrections workshop run by the William James Association, a nonprofit organization that provides art classes in prisons throughout California. The prison studio, in Goodman’s painting, is a space of imaginative possibility, as well as a place constrained by his incarceration and the layered history of the carceral state. His painting is a reflection on the conditions under which art is made within prisons, while also reimagining the space. It foregrounds how art emerges in relation to institutions, whether ones commonly associated with art, like ateliers, conservatories, museums, and galleries, or sites like primary schools, subway stations, public streets, and even prisons.

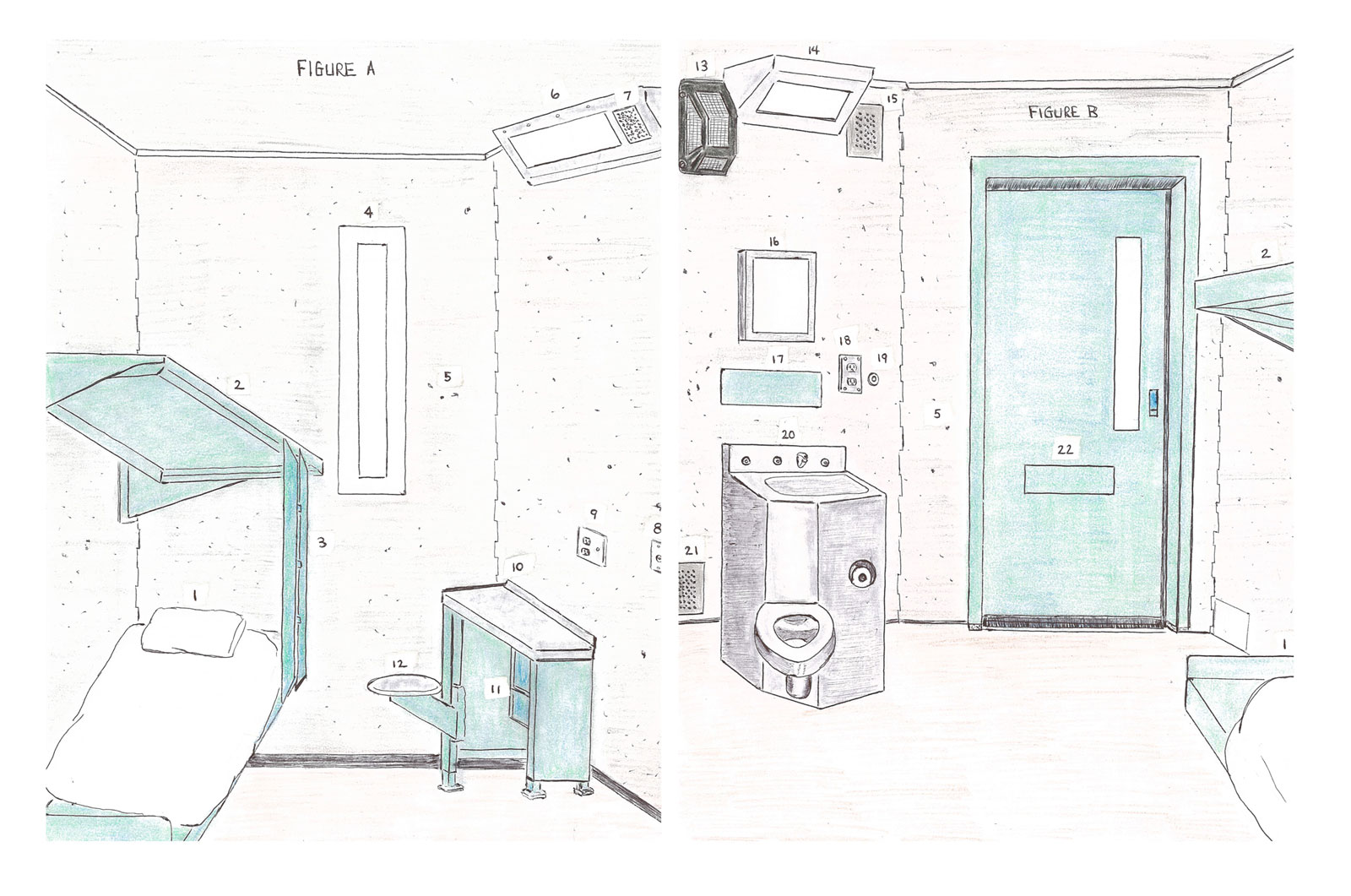

Goodman’s work is an example of what I call “carceral aesthetics,” ways of envisioning and crafting art that reflects the conditions of imprisonment. Every year, incarcerated people create millions of paintings, drawings, sculptures, greeting cards, collages, and other visual materials that circulate inside prisons; between incarcerated people and their loved ones; in private collections of people in prison, prison staff, teachers, and others; and more recently in public domains and institutions like museums, libraries, hospitals, and universities. The majority of art-making in prisons takes place in cells and prison hobby shops, where incarcerated people improvise and experiment with numerous constraints.

One of the challenges of writing about this has been that many of the artists, whether currently or formerly incarcerated, do not have possession of their art, nor any documentation of their work, nor knowledge of how and where their art has circulated. For reasons that have to do with the inequality and exploitation that incarcerated people suffer, art made in prison may be sent to relatives, traded with fellow prisoners, sold or “gifted” to prison staff, donated to nonprofit organizations, and sometimes made for private clients. There are people I interviewed who described their work and practices to me but had nothing to show.

Art made by people in prison can even be lucrative for some institutions, and art workshops and education can function as ways of managing people held captive so that they do not challenge prison authority. At Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, prison art is sold at the biannual rodeo show, bringing in significant profit to the institution, with a percentage for the incarcerated people, who can use it toward commissary or send it home to relatives.

Art made in prisons is commonly described under the rubric of “outsider art” or “folk art.” Other studies have focused on art programs and workshops based on models of art therapy, which grow out of the disciplines of psychology, education, and criminology and which promote exploring creative outlets as forms of healing and rehabilitating people. My main concern about a rehabilitative framework is that in its primary focus on changing the individual, it does not offer an analysis or critique of how the carceral state relies on producing criminal subjects. My engagement with art is through an abolitionist perspective, and while I do not write about prison art as necessarily therapeutic or rehabilitative, I do acknowledge and respect that many incarcerated artists use and understand art-making as part of their healing and coping inside prisons.

Prison art practices resist the isolation, exploitation, and dehumanization of carceral facilities. They reconstitute what productivity and labor mean in states of captivity, as many of these works entail laborious, time-consuming, and immersive practices and planning. Art-making in prison is also important to consider as part of the larger contemporary art world, although prison art rarely appears in public galleries or museums. But like art made in other arenas, prison art exists in relation to economies, power structures governing resources and access, and discourses that legitimate certain works as art and others as craft, material object, historical artifact, or trash. And visual art, the focus of Marking Time, is of course just one form in a broader world of cultural production in prisons, including literature, music, and theater.

Prison art can shift how we think about art collections and art collectors. The primary collectors of art made in prison are other imprisoned people and their loved ones. Substantial collections exist inside cells, storage units, and classrooms of carceral facilities. Prison staff are also collectors of art made inside. Employees of prisons often deliberate with incarcerated people to make art on their behalf and agree on rates within the prison economy, deals made off the books and between people occupying very different positions of power. For this reason, “commission” and “negotiation” are fraught terms to describe arrangements in which unfree artists are asked by people who hold authority over their livelihood to make art in exchange for money, goods, or special treatment.

Generally, when discussing artists, I do not state why an artist was sentenced and imprisoned, unless the artist has requested that I include this information or these details are primary to their story as they tell it. I am not invested in categories of guilt and innocence, which are perilous because they can reproduce carceral logic. My intention is not to play into binaries about good versus bad prisoners, innocent versus guilty people, or those who are deserving of sympathy and recognition versus those who are not. At the same time, not to acknowledge the claims of innocence and eventual exoneration or release of some would be to betray these artists who have entrusted me with their stories and art.

At least four of the artists in my book identify as being wrongfully convicted. Two of them have, in fact, been exonerated by the Ohio Innocence Project, and two were released for time served, negotiated by their attorneys. For each of these artists, their imprisonment for crimes they did not commit propelled their art-making and their political consciousness and critique of prisons, so I speak of their wrongful conviction, exoneration, or release in this context.

I credit my methodology in creating Marking Time to the practices of care and collective survival among black women from whom I have learned my entire life. I recall the Sunday visits with my mom, when I was a young child, to see my uncle, who was locked away in a prison thirty minutes from our hometown. Looking through files after my grandmother died, I was struck by how many times she had borrowed on the surety of her modest home in order to bail out a relative.

My aunt Sharon and cousin Cassandra also exemplified a steadfast commitment over the twenty-one years they spent visiting and supporting their son and brother Allen during his imprisonment. What that entailed for them was laborious, and financially and emotionally taxing. Their care, to which I cannot do justice in these few sentences, included paying monthly phone bills, which sometimes amounted to thousands of dollars because of the exorbitant rates charged by prison phone vendors; ordering an endless array of goods for Allen, again from exploitive vendors; hiring attorneys to review his case; helping to support his daughter, who was only a couple of months old when he went to prison; and journeying at least monthly to wherever he was housed to sit in a prison visiting room across from him. They did it together. They supported each other. They listened to each other and cried when they needed to. This is the foundation of the contemporary movement that is working not only to end mass incarceration, but to do away with prisons and caging entirely.

Adapted from Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, published by Harvard University Press. On April 28 at 8PM, a conversation between Nicole R. Fleetwood, poet and scholar Fred Moten, and artists Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter and Jesse Krimes will be hosted on Zoom to celebrate the book’s publication. The exhibition by the same name will be rescheduled when MoMA PS1 reopens.