The following text is adapted from “The Death of Human Rights,” the 2019 Robert B. Silvers Lecture, delivered at the New York Public Library in honor of the founding co-editor of the New York Review, who died in 2017.

Though my title fits the grim tone of our age, the truth is that this is a joyous occasion for me. With the notable exception of my father, no man meant more to my life than Robert B. Silvers. Bob gave me my first job, taught me to edit, and then, for nearly three decades, published my writing on Haiti, on the Balkan wars, on the Iraq war, on American presidential elections from Bush v. Gore to Barack Obama to Donald Trump. Whenever I was grinding away at my desk with little result, I would pick up the phone in desperation and dial the New York Review number and, whether it was five in the afternoon, eleven at night, or three in the morning, Bob was always there to pick up the phone. He taught me that, too: the necessity of devotion. Struggling to work these past few years without that telephonic lifeline has been a melancholy business, and it gives me great comfort to address here the many who worked with him and knew him. Bob “has become his admirers”— as Auden said on the death of Yeats—and I like to think that all of us who benefitted from his vision will together conjure Bob for the time we are together. That thought gives me comfort and hope, if also trepidation.

I’ve come to join you from the edge of the continent: golden California, the land of the future, where the forests are parched and crackling and the harsh smoky winds swirl through the towns and blow the tree branches against the electrical wires, causing apocalyptic conflagrations. In one fire, a year ago, eighty-five people, some caught in a great swarming traffic jam as they struggled to flee their town, were burned to death. Now in California, when the wind blows, we turn off the electricity. Our candles flicker and our food defrosts and we sit in the darkness and smell the smoke. Pondering that darkness not long ago, there came to my mind a joke from the final days of the dreaded Ceaușescu regime in Romania, in the late days of the cold war. The joke went like this:

Question: What did the Romanians use for light before they had candles?

Answer: Electricity.

Such is now true, alas, for California. I have drawn from this cutting-edge climate-change strategy a general theory that I’d like to propose to you now: history as we know it has ground to a halt and is now slowly moving backward. In California, always at the cusp of the future, we have learned that the only way to deal with the consequences of our industrial development and excessive growth is to turn off the electricity and light the candles. In Washington, our proud post-Enlightenment democracy has lumbered past the “end of history” that was declared in 1989—when we took pride that all roads had led finally to political liberalism and democracy, that is: to us—and is now slipping back, back, back, into pre-Enlightenment tribalism, cultism, Big Man autocracy. And finally, that grand achievement of the Enlightenment, scientific method and the worship of the fact, has deteriorated into the end of truth, the distrust of proof, and a basic disagreement about what facts are and what they mean. The Paranoid Style in American Politics, which characterized the extreme right when Richard Hofstadter published his famous book in 1964, has now enveloped at least half of our politics—and the portion is growing. Do you find this too sweeping a statement? I offer you as the grand exhibit for this epistemic crisis… the impeachment hearings. No more solemn public ceremony is supposed to exist in our democracy and yet, in the basic schism they exposed between the parties about what constitutes evidence, facts and wrongdoing itself, these hearings quickly transformed themselves into an enervating and emblematic farce.

Human rights, which is my subject today, was perhaps the supreme Enlightenment achievement and a utopian project if ever there was one. Consider for a moment two sentences familiar to every American schoolchild:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure those rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…

The history of the human rights project is complicated, with many turnings, but it would not be wrong to say that for the United States, which—even as it pursued its neo-imperial ambitions—championed the human rights revolution that began after World War II, it all began here, in those two sentences, which identified human rights as natural rights, existing independently; drew the legitimacy of government from its respect for and protection of those rights; and—and this is vital—in its grounding in democratic consent. This vision, firmly rooted in the multilateral United Nations system, as well as in a proactive, evangelicizing foreign policy, was to spread, ever so gradually, from the United States and Europe throughout the so-called underdeveloped world, and would eventuate in universal human rights and democracy, formalized in and bolstered by increasingly elaborated and responsive multilateral institutions. Thus, at the end of time, beneficent world government. Thus the end of war and conflict. Thus: utopia.

Advertisement

It is not enough to say that we are far from that today: such is the reality of utopian visions. For the first time since the late Forties, Americans and their government are demonstrably headed in the opposite direction. It is not simply that a few hours by air to the south at Guantánamo Bay lies a prison, whose forty remaining “detainees,” as we have been taught to call them, are serving in essence life sentences for crimes for which they were never tried and never convicted. It is not simply that many of those prisoners can never be tried because they were “disappeared”—secretly arrested and kidnapped—and tortured: “legally” tortured, tortured under color of law. It is not simply that, as we speak, above half a dozen countries in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones, are flying, hour after hour, day after day, and every week or ten days launching missiles at unsuspecting targets on the ground, killing putative militants and civilians alike, killing even, on occasion, high-ranking generals of other countries—killing, perhaps, five thousand people during the last decade and a half, and counting. It is not simply that assassination has become a mainstay of US foreign policy. It is that these things are the new normal: torture; cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; indefinite detention; assassination; extra-judicial killing. This is not who we are, as President Obama was fond of saying. And yet, it is what we do.

It is not only these things. It is that our current government is the first since World War II to have renounced the human rights agenda altogether. This renunciation, we are told, is in the service of a new “Principled Realism.” The president has delivered several speeches to the United Nations that don’t even include the phrase “human rights”—or rather, in one case, including those words only to announce that the United States is withdrawing from the Human Rights Commission. When a close ally, which depends on the United States for its protection, lures a journalist—an American resident—into its consulate and murders and dismembers him, the American president cannot even bring himself to denounce it and his secretary of state is photographed days after the event smiling as he grasps the hand of the autocrat, who, US intelligence has determined, is personally responsible. Although hypocrisy has long been a vital part of the United States human rights agenda, hypocrisy has now devolved into abandonment. Perhaps, after the torture, the indefinite detentions, the extra-judicial killings, such a final stripping off of the mask was inevitable. But I don’t think so. This was a result of calculated policy.

Hypocrisy, as I say, has been an integral part of the US human rights agenda from the start. Again and again, we saw it feature prominently in the American government’s actions in the years of the Pax Americana. Proudly fashion the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—and overthrow the elected governments of Iran and Guatemala. Sign the Genocide Convention—and collaborate with the Indonesian government in its massacre of hundreds of thousands of so-called Communists. Negotiate the Convention Against Torture—and supply intelligence information and training to the Argentine and Salvadoran armies on whom to torture and how. Crusade for democracy—and meddle repeatedly in elections. When the meddling doesn’t work, help in overthrowing leaders whom you don’t want but the people, alas, do. “I don’t see why,” intoned Henry Kissinger, “we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.” Kissinger, of course, was speaking of the elections in Chile, which had brought to power a leader he and President Nixon would help to overthrow.

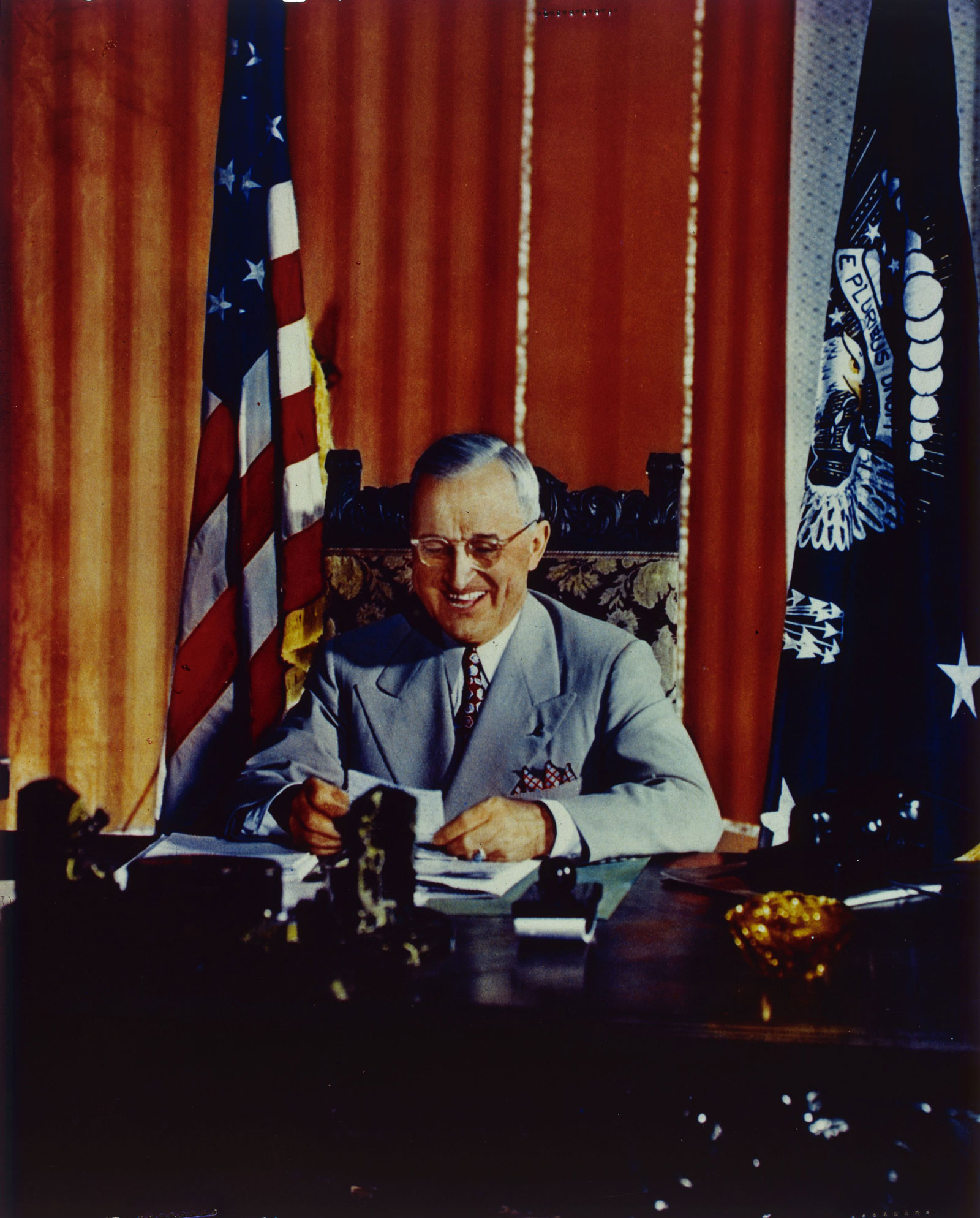

Kissinger’s voice, however sardonic, is the embodied voice of a great power, concerned with high politics between nations, not the paltry aspirations of the people. After World War II, the United States had become not only a permanent great power but the status quo power that saw itself as standing in the way of upheaval and revolution. That this happened was by no means predetermined. It came about during a few weeks in 1947, when British officials of the collapsing empire let US diplomats know that they were no longer able to support the struggle against Communist insurgencies in Greece and Turkey. Would the United States step in? The story is immensely rich and complicated—I’ve written about it in more detail elsewhere—but the result was direct and clear. The United States took on a permanent role in the politics of postwar Europe and in world affairs. This was unprecedented in American history; indeed, the Founders, notably Presidents Washington and Jefferson, had warned explicitly and eloquently against it. To make this commitment, President Harry S. Truman had to convince Congress to vote the funds, and to convince those in Congress, he had to convince the people who voted for them. Or as one prominent senator advised, the president had to make a speech and “Scare hell out of the American people!”

Advertisement

In the event, Truman did just that, but he did something else as well, as we’ll see in these famous words that came to be known as the Truman Doctrine:

At the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life. The choice is too often not a free one.

One way of life is based upon the will of the majority, and is distinguished by free institutions, representative government, free elections, guarantees of individual liberty, freedom of speech and religion, and freedom from political oppression.

The second way of life is based upon the will of a minority forcibly imposed upon the majority. It relies upon terror and oppression, a controlled press and radio, fixed elections, and the suppression of personal freedoms.

I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.

I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way.

As George Kennan, Walter Lippmann, and other alarmed realists within and without the government quickly pointed out, the American president had gone far beyond “scaring hell out of the American people.” He had proclaimed a worldwide ideological mission to “support free peoples”— and, by extension, promote democracies. A limited brief to support Greece and Turkey had become an evangelical call to spread freedom throughout the world. Powerful as the United States was, it didn’t have the power to accomplish that. Where would it stop?

Truman was an able politician. His doctrine was popular. Americans, if they were going to pay for a permanent military establishment of the kind the country had always abjured, wanted it to do something beyond ward off fear. It was reassuring that American power would promote freedom. This mission dovetailed very well with the institutions that came to define postwar American policy, not only the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Marshall Plan but the entire multilateral structure erected under the United Nations. Through these institutions ran a well-anchored idealism that, as we have seen, was prefigured in the founding documents of the country and was replenished with eloquent doses of presidential rhetoric during the great wars of the twentieth century. Such rhetoric confronted a nascent problem that had confounded powerful nations since Athens, which I have called “the Athenian problem”: in a democracy, how do you persuade the people to support an imperial foreign policy?

If they were going to intervene abroad, Americans wanted to do so in a higher cause, and, of course, promoting democracy and human rights was part of every civics class—everywhere, in fact, that the Declaration of Independence was taught. It was an ingrained part of Americans’ self-image. It was, as President Obama so often said, who we are.

As a matter of fact, we are a whole lot more. We are a superpower and the leader of two enormous alliances, NATO in Europe and the Japan–South Korea alliance in Northeast Asia, and since the Forties, we have guarded those alliances with hundreds of thousands of troops. Since then, we have guarded the international sea lanes and perilous choke points like the Straits of Hormuz with hundreds of warships. And if these formidable mainstays of American power were not enough, we backed these guarantees up with tens of thousands of nuclear weapons on constant alert—nuclear weapons that, our doctrine said, and still says, we would be willing to use first against conventional forces in a crisis. As much as those oft-intoned words in our founding documents, these alliances and warships and weapons, too, are “who we are.” And the fact is that over the last half-century and more, when the dire words “national security” were uttered, human rights would come to appear expendable. (In my first book, The Massacre at El Mozote: A Parable of the Cold War, I wrote about a particularly clear and ugly example of this during the Salvadoran civil war of the 1980s.)

Did this subjugation to national security concerns mean, as some claim, that for the United States, human rights were simply a bit of clever propaganda used to pretty up a ruthless empire? I don’t think so. Most obviously, the stated ideological commitments were embodied in institutions, not only the multilateral ones of the United Nations system but also the doctrinal ones of international law with its vast compendium of post-Nuremburg treaties and agreements, and the complementary institutions set up within the American foreign policy bureaucracy to put them into effect. (These secondary institutions, in turn, spawned their own tertiary network of vital non-governmental human rights organizations, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the Open Society Institute, and many, many others.) Fidelity to those commitments varied greatly by administration, of course. Traveling around the world as a young reporter, I met many former political prisoners who believed they owed their freedom to the aggressive human rights policies of Jimmy Carter. There is no doubt the democratic revolutions in Haiti and the Philippines, for which Ronald Reagan later took credit, owed much to Carter’s evangelicism. So, in much more complicated ways and with rather more mixed results, did the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua; and even the Islamic Revolution in Iran, which has been a critical pivot of American foreign policy in the region ever since.

It is notable that, by the inauguration of President Reagan, human rights had become so institutionalized as a bi-partisan American policy goal that even leaders of the right wing of the Republican Party would pay lip service to it. Thus, in Central America, the byword of the Reagan policymakers became: of course, we all agree human rights promotion is a main policy goal in Central America, we just have different ways to promote it. The Reaganites claimed to be doing so not only by supporting the murderous Salvadoran Army but also by pushing for elections—and by insisting that killings of civilians in the war were actually declining, thus making the argument one over facts, not philosophy. (And Americas Watch, as it was then called, rose up in turn to investigate those claims and to challenge them with its own independent human rights reporting.) It is roughly at this point in the late cold war that we see a kind of splitting of human rights ideology between its international humanitarian backers, mostly in the Democratic Party, and the neoconservatives, mostly by then in the Republican Party. The latter promoted human rights through democratization, the former through more direct interventions to protect human life. They were on different sides in Central America. Partisans of these strands would go on competing during the genocidal wars of the 1990s in Bosnia and Rwanda—which produced the ideology of international humanitarian intervention or Responsibility to Protect (R2P)—and finally joined hands over their support of the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

And so we come to the “post-cold war era,” one of those weird expressions, like nonfiction, that defines something by what it is not, or by what it comes after. Let’s rather call the time between 1989 and the present day the “era of predominance.” After the fall of the Berlin Wall, strategists in Washington decided not to end the cold war but, in effect, to continue it with the United States as sole participant. “We must maintain the mechanism for deterring potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role.” So wrote, in 1992, a then little-known Pentagon official by the name of Paul Wolfowitz. And just who were those “potential competitors”? Wolfowitz meant, of course, Germany and Japan, the United States’ former enemies and now its key allies. Instead of being dismantled after its cold war victory, NATO was enlarged eastward, tranche by tranche, until it pushed up, eventually, to Georgia and Ukraine—to the borders of Russia itself, with wholly predictable results. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, in part the result of decades of American support of dictators in the Middle East and a complete failure to promote political development there, the US launched a so-called global war on terror. Defense spending shot up and it has remained far beyond its peaks during the cold war. “America has and intends to keep military strengths beyond challenge,” President George W. Bush declared in 2002, “making the destabilizing arms races of other eras pointless and limiting rivalries to trade and other pursuits of peace.” A couple days after the September 11 attacks, the president had declared his determination to “rid the world of evil.” Thus the Truman Doctrine—on steroids.

In retrospect, the era of predominance holds within it three great catastrophes that delegitimized the American bipartisan elite and paved the way for the rise of Donald J. Trump: the opening to China, the invasion and occupation of Iraq, and the economic collapse of 2008. China’s evolution, of course, has been a direct slap in the face to Fukuyama’s “end of history” theory, that all political economic systems will evolve toward democratic capitalism. Open up China to world trade, the theory went, and the country would follow a slow but certain evolution toward a more open, democratic society in which human rights were increasingly respected and democratic capitalism would be the certain end result. It didn’t work out that way. China became an astonishing example of a kind of ruthless Leninist capitalism, a model that has become increasingly influential around the world, even as the regime cracked down more savagely on human rights with an all-encompassing totalitarian repression that even Stalin lacked the technology to impose. One could cite the Uighur detention camps, a relatively old-fashioned kind of repressive instrument, which hold perhaps a million people. Or the more insidious social credit index, by which, using big data, facial recognition, and other highly developed forms of technology, the regime monitors every individual’s behavior—his or her travel, purchases, traffic tickets, online activity, everything—and the state confers or withholds privileges accordingly. It is a vivid vision of twenty-first-century totalitarianism and it is being implemented as we speak. As Ken Roth of Human Rights Watch put it recently, “With this technology, the regime will no longer even need prisons.”

The dramatic misjudgment of China and the speed with which its ferocious Leninist capitalism “stole our jobs,” particularly in the Midwest manufacturing heartland, form one of the two great foreign policy disasters that destroyed the credibility of the old American elite. The other was the Iraq war, the consequences of which continue to play out in the Persian Gulf as we speak. The dramatic rise of Iran, the shadow war in the Gulf that is being fought right now, the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, all can be traced directly to the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The invasion—a war of choice that its advocates boasted would be a cakewalk and unleash a “tsunami of democracy” across the Middle East—began with lies. Lies about so-called “weapons of mass destruction” that were quite apparent in the discussion during the lead-up to the invasion. When then National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice warned repeatedly that “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud,” implying the Iraqis were about to acquire a nuclear weapon, she was lying. There was never any persuasive evidence that Iraq retained an active nuclear program and very compelling evidence that it did not. The International Atomic Energy Agency published a report in the weeks before the American-led invasion that proved conclusively there was no nuclear program. The New York Times published those results—on page A17. I have no doubt that many in the Bush administration and its hangers-on among supporters of the war, which included many prominent Democrats and many so-called liberals, believed the underlying truth of what they said, even as they spouted dubious assertions about weapons of mass destruction. Other perhaps convinced themselves, in Hendrik Hertzberg’s astute phrase, that they were “framing a guilty man.” But they lied—and those lies did much to destroy the credibility of the old foreign policy elite.

Even more, of course, they were dramatically wrong about the consequences of this war of choice. Five thousand American deaths and perhaps half a million Iraqi deaths is the most obvious consequence. The destabilization of much of the Middle East is another. The rise of Iran as leader of the so-called Shia Crescent stretching from Tehran to Beirut is a third. The besmirching of the United States’ reputation by the Abu Ghraib photographs—photographs that will stand forever as indelible images of American torture and American hypocrisy—is a fourth.

Finally, a less tangible consequence is the identifying, and shaming, of the entire “reality-based community” and the challenge presented to it by those who “create their own reality.” Indeed, if we seek to find the roots of our current epistemic crisis surely this is the place to start: the famous words of an unnamed aide to George W. Bush (widely believed to be Karl Rove, known at the time as “Bush’s brain”) who opined to the journalist Ron Suskind the signal words of the era:

The aide said that guys like me were “in what we call the reality-based community,“ which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” […] “That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors […] and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

Here in a nutshell is our epistemic crisis: truth is a function of power, not of the independent perception and judgment that, it was thought by our Enlightenment founders, could bring power to heel by the use of facts and evidence. Karl Rove’s “history’s actors” turn that idea on its head. George Orwell, who remarked that “from the totalitarian point of view, history is something to be created, not learned,” would have understood.

Iraq and its aftermath had the effect of dramatically undermining the credibility of the so-called Blob, the foreign policy establishment. Both sides of it—for, of course, most of the most powerful Democrats (especially those with political ambitions, like Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, among others)—supported the war. So, it should be added, did many prominent liberal intellectuals. Many of my friends, as well as The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New York Times… you name it. As I mentioned, this was the fascinating moment when the international humanitarian vision of human rights, advanced after the genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda in the Responsibility to Protect movement, crossed paths with the democratization vision advanced by the neoconservatives. Thus, when I argued in various venues against the Iraq war, I found myself arguing not only against William Kristol and David Frum and other neocons but also against Christopher Hitchens and Michael Ignatieff. These liberals were parroting the Bush administration arguments that invading Iraq would advance human rights as well as democracy. Or perhaps the Bush administration, in adopting that argument, was parroting them.

In any event, it is safe to say that no foreign policy masterminds lost their jobs for supporting the Iraq invasion, and neither did any of their journalist and pundit cheerleaders. Indeed, as I myself have found, those who argued against the war were never terribly popular within the precincts of power, in office or out. As Paul Krugman remarked in 2007, “on our national discourse, at least in DC, you’re still considered ‘not serious’ if you were right about Iraq.” Not so in the rest of the country. Donald Trump may have told eighteen thousand lies and counting, but there is a reason he claims that he publicly opposed the war. It sets him apart from the delegitimized elite that cheered on the troops on their victorious run to Baghdad.

Barack Obama was lucky enough to be an unknown state senator in Springfield, Illinois, when the war began and thus in a position to oppose “stupid wars.” No one noticed at the time—why would they?—but that lucky accident of timing would make him president. He came in vowing to abolish torture and to close Guantánamo within a year. Guantánamo remains open, of course, and those who designed and approved and practiced torture remain unpunished. Indeed, the succeeding two Republican presidential candidates, Mitt Romney and Donald Trump, ran on a pro-torture platform.

Obama did withdraw from “stupid wars,” notably in Iraq, and transformed the global war on terror from shooting wars with troops on the ground to the so-called “light footprint,” in which the fighting would be delegated to unmanned drones and lightening quick raids by special forces operators. This is called the strategy of decapitation. Or, less politely, assassination. It has a lot of advantages, the most important of which are political: you don’t put American troops at risk and Americans don’t care about civilians killed on the other side of the world. There is a downside to this kind of warfare, however. Once you decapitate an organization, the head grows back, and grows back again, and again. Very often, the new leader is more militant than his late predecessor. In any case, he will soon demand attention of the same kind. That is why the Israelis refer to a strategy of drone assassination—which they devised, in Gaza—as “mowing the grass.” Once you mow it, the grass grows back, and you have to come back and mow it all over again.

Thus the endless wars that our current president is vowing to end. He came to power talking about the catastrophe of China and the disaster of the Iraq war, and I for one, as a reporter at his rallies, found many, many people who agreed with him. Both of those issues not only discredited the foreign policy establishment but undermined the elite generally and delegitimized the very idea of expertise and meritocracy. Thus those in the reality-based community were shown to be not only liars but also corrupt and incompetent fools, with Hillary Clinton, who voted for the Iraq war and whose husband was the president held most responsible for throwing open the American economy to job-destroying, China-centered globalization, standing as the perfect emblem for all of them.

Trump vowed to take down the former empire and to an astonishing extent he has succeeded. He is not a builder but a destroyer. At each borderland of the former empire—Ukraine, North Korea, the Persian Gulf—fires are burning. NATO, the French president tells us, is “brain dead.” If Trump didn’t make it so, he has pushed it hard toward intensive care. The war largely caused by NATO’s expansion continues burning fitfully in Eastern Ukraine, complicated now by the president’s typically predatory attempt to force the Ukrainians to do his political bidding. In the Persian Gulf, Saudi Arabia runs amok, not least because of Trump’s unabashed enthusiasm for dictators and strong men, which we have seen dramatically play out on the Korean peninsula as well, where the president, in an unlikely coupling, has fallen in love with Kim Jong-un. His lover has continued his nuclear development and his testing of shorter-range weapons.

As always with Trump, one must look first not to ideology but to psychology and personality. His view of life is cruel and rapacious. Life is a tooth-and-nail struggle. One party wins and dominates, the other loses and is dominated—and then, usually, is demeaned and humiliated. Thus alliances, human rights, altruism itself, all these perplex him. He doesn’t believe in them, thinks they are clever covers for something else. He imbibed the American postwar myth with his breakfast cereal: the US won World War II, didn’t take anything or ask for anything in return, generously established alliances, and protected Germany and Europe and Japan out of the goodness of its heart. Trump believed the myth, and to him it proved nothing more than that Americans are suckers. Those allies are getting something for nothing. Because he views the world through the prism of money, he can’t understand the benefits of national power in its essence. Why should we have bases in Japan and South Korea—unless they’re paying us for them?

I mentioned Trump’s failure even to criticize the Saudi crown prince for murdering Jamal Khashoggi. The fact is, the president revels in cruelty because it affirms to him that this is how the world really works. All the rest is hypocrisy from those who won’t admit the truth. We should be clear on this. Though the Saudis likely wouldn’t have dared commit such an overt crime under other administrations, had they done so, other presidents would have denounced the affair but not broken relations. The Saudis wouldn’t have lost United States patronage but there would have suffered damage. It’s possible the crown prince would have been forced out at the insistence of its patron. Eventually, the incident would have passed, relations would have returned to normal. And neither the Saudis, nor anyone else, would have dared do something so brazen and disreputable again. Thus the hypocrisy, and grim usefulness, of US human rights policy.

Trump would see such actions as pretentious—and useless—hypocrisy. He glories in stripping the hypocritical skin off things and his followers love him for it. His “truth-telling,” so loud-voiced and bold, delights them—and the more it appalls the liberals, the better. It convinces his followers that he, unlike his opponents, says exactly what he’s thinking, and what he’s thinking is what they’re thinking. Trump came to power advocating torture and killing the families of terrorists. “You’ve got to go after the families,” he said. He has not done that, to our knowledge, but Trump relaxed the rules of engagement in the war against Islamic State, which probably resulted in the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of civilians in Northern Iraq and Eastern Syria. At the same time, wary of the political costs of endless wars that he ran on ending, he has continued Obama’s “light footprint” and his Afghanistan policies while noting that “If we wanted to fight a war in Afghanistan and win it, I could win that war in a week. I just don’t want to kill 10 million people.” Nuclear threats—“totally destroying North Korea,” as he threatened to do at the United Nations, wiping out Iran, etc.—unheard of with presidents before him are a regular part of Trump’s rhetoric and make one shudder about what exactly he would do in a second term. More recently, he has pardoned convicted war criminals, another unprecedented step, and has insisted that at least one of them should be returned to his active unit. “We train our boys to be killing machines then prosecute them when they kill!” It is an understatement to say that American officers, not to mention soldiers, Marines, and airmen, who regard themselves as professionals, do not agree with the president’s characterization of them as “killing machines.” But here again, many of his followers see the president as exposing the hypocrisy of those who hold to the laws of war.

Finally, the president has directly attacked the United States-led multilateral order and proclaimed self-interest—the new nationalism, or principled realism, depending which document you consult—to be the abiding principle of US and indeed universal foreign policy. “The future does not belong to globalists,” the president declared at the United Nations. “The future belongs to patriots.” He added that “Globalism exerted a religious pull over past leaders, causing them to ignore their own national interests. But as far as America is concerned, those days are over.” And, of course, he has put his money where his mouth is by simply tearing up treaties, most importantly the nuclear agreement with Iran, but also the Global Climate Accord and a number of others, without any legal basis. Thus nationalism in action.

He has proclaimed cruelty as a national interest. His talk about renewing torture as a policy was not put into action, largely because of resistance from James Mattis, his first secretary of defense, but his proud advocacy of it, together with his predecessor’s failure to close Guantánamo, has helped to enshrine torture as an institutionalized blot in American history. Meantime, in moving to relax rules of engagement for drone and air bombardment in the war against the Islamic State, and in his killing of Soleimani, he has inscribed assassination and widespread civilian “collateral damage” as permanent features of American policy. Even more, his periodic flirtation with the idea of using nuclear weapons—against North Korea, against Iran, against Afghanistan—must be taken as a worrying sign of his own preoccupations. This president wears his thoughts always on his sleeve. We are privileged, and burdened, to know what he is thinking, all the time. This is what it’s like to live in the “age of the big man.” His thoughts are our thoughts. And those thoughts, especially when it comes to the country’s nuclear arsenal, are deeply troubling ones.

To acknowledge Trump has stripped away the useful hypocrisy of American human rights policy is not to say that that policy is quite dead. Certainly, the United States’ leadership in human rights has come to an end and perhaps this is as much owed to President Bush’s approval of torture and President Obama’s failure to punish torture as to President Trump’s enthusiastic advocacy of it. In retrospect, American leadership ended when that first prisoner was strapped to the waterboard under color of law. And certainly human rights are dead in the words and actions of our president, the highest symbolic exponent of American values. But the president is not everything. The institutions set up to promote human rights, in the State Department and elsewhere, still exist—and they go on functioning, however feebly, like a limb that still twitches after the brain has died. Multilateral institutions in the United Nations, many of which owe their existence to American initiative, still exist and function. Indeed, even as the United States lays it down, other institutions are taking up the human rights banner. The European Union, for example, has pushed back, however weakly, against Viktor Orbán’s so-called illiberal democracy in Hungary. The Europeans have spoken out against Saudi war crimes in Yemen, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation has done the same against the Burmese regime’s murder of the Rohingya. In Venezuela, we see that the Lima Group, consisting of a more than a dozen Latin American democracies and Canada, has launched a UN investigation and taken Venezuela to the International Criminal Court. And representatives of non-governmental organizations, from Human Rights Watch to Amnesty International to the Open Society Institute and many others less well known, are working hard around the globe. All of these will go on exposing wrongdoers, and sometimes, in the case of the International Criminal Court, even without US participation, punishing them.

The spread of inexpensive new technology has had a decisive effect here. So-called open-source methods—social media searches, geo- and chronolocation of photos and videos, satellite photo analysis and many other rapidly developing techniques—have revolutionized reporting on human rights abuses, allowing, for example, The New York Times to identify Khashoggi’s killers as close aides of the crown prince, even while the Saudis were claiming they were unknown actors. These techniques ensure that, more than ever, horrible acts will be uncovered. It is one of the unmentioned precepts of journalism that once wrongdoing is revealed, those wrongs will somehow be righted—that (as I have detailed before) revelation will inevitably be followed by investigation and then expiation. We have entered an era in which, more and more, that belief—journalism’s secret bias toward optimism—will be put to the test. Increasingly, citizens are taking matters into their own hands, and during the last year we have seen people take to the street, at least in part for human rights causes, in Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Chile. They are demonstrating for the rule of law and for an accountable government and it is safe to say that now that they have started they will not stop. Perhaps that is the simple teaching to be drawn from the era of hypocrisy now passing: that in the end human beings want human rights and are willing to fight for them—whatever the American president does or does not say.