On January 24, 1848, miners found gold in Coloma, fifty miles east of Sacramento, but it wasn’t until May 29, when a local newspaper published an editorial about a country “resound[ing] with the sordid cry of gold! Gold! GOLD!,” that the California Gold Rush began.

Later that year—or early the following year, records vary—a Chinese woman from the port city of Guangzhou set sail on a steamboat headed for San Francisco. Ah Toy was only the second Chinese woman to land in San Francisco, the first being the servant of a trader who had arrived a few months earlier. Although Ah Toy had the bound feet of an upper-class woman, she traveled alone, and arrived in San Francisco aged about twenty, with no means of supporting herself other than her own body.

I learned about Ah Toy while researching a story about a prostitution raid in Florida in 2019, during which all the massage parlor workers who were arrested were either immigrants or migrant workers, all from China. Some posted bail and were released; others were transferred to immigration custody, where they waited to be deported. The customers who were arrested were all men, mostly white. All were let go without a citation.

Along the way, I learned that anti-immigration legislation often ends up doubling as anti-prostitution legislation, as it is often women—frequently women of color, including those who are undocumented or in otherwise precarious positions and are locked out of traditional labor markets—who enter into sex work.

Ah Toy’s story is part of this history. I immediately took to her, in part out of professional interest, but also for personal reasons. People of color live in a world that was built without us in mind; whenever we see representation—in history, media, or art—it is hard not to feel intensely curious.

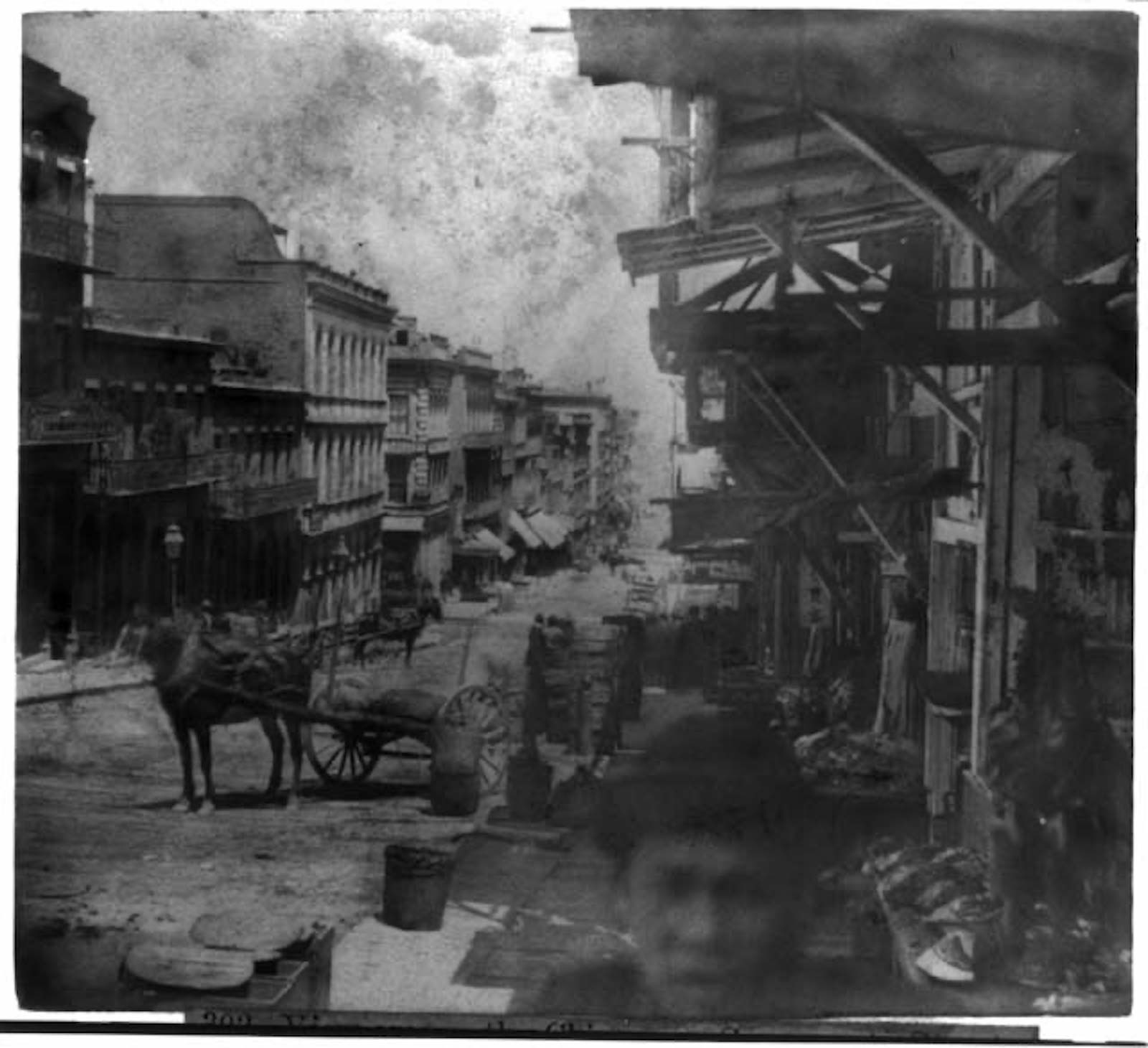

Ah Toy’s aim in immigrating to America, according to Judy Yung’s 1995 book Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco, was “to better her condition,” but options for a single woman speaking no English were limited then, as they are now. Eventually, she set up a shanty on Clay and Kearney Streets, in modern-day Chinatown. This neighborhood would later become known as the Barbary Coast, the city’s vice district, its notoriety stemming in part from the way men and women of different races and classes mixed. There, working out of a shack that was four feet wide and six feet deep, Ah Toy began offering her services to miners, becoming the first recorded Chinese prostitute in the new world.

By all accounts, she was beloved. Miners would “break into a run” for the famously beautiful Ah Toy when they docked in San Francisco, according to a 1964 book by Curt Gentry, The Madams of San Francisco. The French writer and San Francisco resident Albert Benard de Russailh wrote in his journal at the time: “The Chinese are usually ugly, the women as well as the men; but there are a few girls who are attractive if not actually pretty, for example, the strangely alluring Achoy, with her slender body and laughing eyes.” Charles Duane, a “fixer” for California Senator David Broderick, called her “the finest looking woman I have ever seen” in his 1881 memoir.

Ah Toy had arrived in San Francisco just as California was becoming a state, in that interstitial time before the introduction of laws that would establish structural bias against women and people of color, and before the traditional order, religious and social, that pertained elsewhere in the US could assert itself. (The first clergyman of the Bay Area, Timothy Dwight Hunt, did not arrive until October 1848 from Honolulu.) Though their power would diminish with the closing of the frontier, women, and women of color, prospered—for a time.

*

In the rough and rowdy San Francisco of the Gold Rush, women were an uncommon sight, and some were able to use this to their advantage. There are accounts of miners dashing out of saloons to hear a female choir sing at a schoolhouse, and reports of enterprising café owners charging men admission to a dining hall where naked women reclined in “indecent poses.” Women walking alone would find themselves assailed by admirers. A widow, who came by ship from New York after losing her husband at sea, received three marriage proposals within her first week in San Francisco.

This Wild West brand of adulation extended to prostitutes, too. They had begun arriving in San Francisco as early as 1848, but it wasn’t until the following year that they came in meaningful numbers. By the end of 1849, there were seven hundred prostitutes, out of a total population of between 20,000 and 25,000. It was not uncommon to see men at the harborside greeting steamships carrying prostitutes, notes Rand Richards in Mud, Blood, and Gold: San Francisco in 1849 (2008), and then staying for an immediate auction to secure their services: “Gentlemen, what are you willing to pay, any one of you, right now to have this pretty dame, fresh from New York, pay you a very special visit?”

Advertisement

Because news of the Gold Rush spread to Central and South America through Mexico first, most of the first-generation prostitutes were Latina; they set up their own house, known as Washington Hall. White prostitutes worked at a more upscale brothel on Washington Street, opened by a New Orleans madam, and were able to charge a higher sum, sometimes twenty times more. There was, at first, no obvious niche in this market for a Chinese woman.

*

After her initial success, Ah Toy struggled as a single businesswoman, but within her first year in California, she had established herself not only as a prostitute but also as a prominent madam. She opened a brothel on Pike Street (present-day Walter U. Lum Place) and hired Chinese women, who had begun arriving in California’s ports by the mid-1850s, to work for her.

Most Chinese prostitutes in San Francisco worked in groups, either in parlor houses or in street-facing rooms, sparsely furnished with a washbowl, a bamboo chair, and a hard bed. Typically, lower-ranking prostitutes—called loungei, roughly translating to a woman always holding her leg up—worked out of small rooms in alleys busy with other prostitutes soliciting clients among the day laborer and sailor class, for as small a sum as twenty-five cents, or the equivalent of eight dollars today. According to Yung, women “took turns enticing customers through a wicket window with plaintive cries of ‘Two bittee lookee, flo bittee feelee, six bittee doee!’” or twenty-five, fifty, and seventy-five cents.

Parlor houses of the type that Ah Toy ran, in contrast, comprised well-appointed rooms, usually in the stories above ground-floor commercial premises, with teakwood and bamboo furniture and embroidered cushions. The “exotic” atmosphere and the cheap rates of the Chinese establishments (as well as a rumor that Chinese women had vaginas that ran “east–west” instead of “north–south”) attracted many patrons, both white and Chinese.

Ah Toy ran her small business with determination and guile, successfully defending it against legal challenges. Over the course of her working life, according to official documents, Ah Toy appeared in court more than ten times, at first as a plaintiff bringing lawsuits against men who had wronged her, and later, as a defendant against vice charges. (Another tally puts the number of her court appearances at fifty during her first three years in San Francisco.)

Her most high-profile case, in 1849, was a lawsuit against several johns who had scammed her by paying for their time with brass instead of gold. During the trial, Ah Toy wore a bonnet, an apricot satin jacket, and willow-green pantaloons; her hair was in a bun, and her face was whitened using rice powder. When the judge asked her to produce evidence, she left and returned with a porcelain bowl filled with brass shavings. This, as Richards relates, brought “a great shout of laughter from the spectators.” (Nevertheless, the judge ruled in favor of the defendants.)

A couple of years later, Ah Toy filed a criminal complaint claiming that some men had stolen a $300 diamond brooch from her. The trial, which lasted for several days, concluded when the pin was recovered after the thieves tried pawning it for cash. Over the next few years, Ah Toy continued to appear in court, always cutting a figure in clothes of “the most flashing European or American style,” according to Richards, and boldly speaking about the corruption that then plagued the judiciary. That a Chinese immigrant brothel owner so readily availed herself of the court system showed remarkable resolve.

*

In time, however, operating in the San Francisco sex trade became more and more fraught for the pioneering Ah Toy. More Chinese immigrants began arriving in San Francisco in 1849 and the early 1850s, driven by crop failures at home, as well as by the carnage of the Taiping Rebellion and the Opium Wars. By the end of that decade, there were around 35,000 Chinese in America.

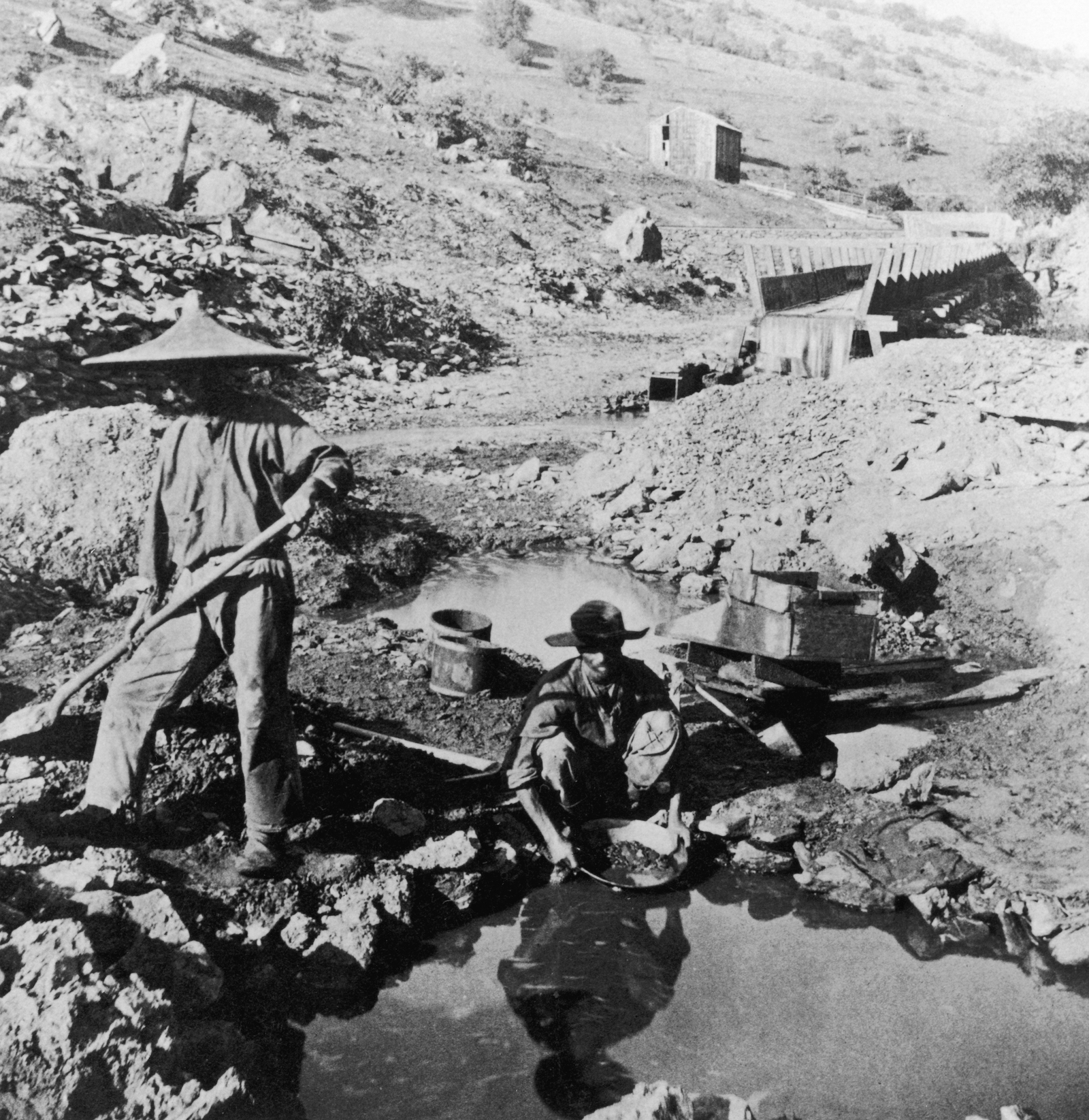

Initially, they were warmly received as much-needed labor, but as the gold ran out, throughout the 1850s, so did the welcome. In fact, anti-Chinese rhetoric had been building for some time, since the 1830s when Chinese immigrants began arriving in other parts of America, but it wasn’t until the 1850s and 1860s that this nativist animus began solidifying into political action and legislation. First came the Foreign Miners’ Tax Acts of 1850 and 1852, which charged foreign miners, most of whom were Chinese, a monthly tax, and accounted for more than half the state’s tax revenue between 1850 and 1870. Other lesser-known special taxes were levied as well, on Chinese fishermen, laundrymen, and brothel owners.

Advertisement

Legislators passed an additional set of local ordinances that did not explicitly single out the Chinese community, but, writes Yung, “obviously were passed to harass and deprive them of a livelihood.” These included the cubic-air law, which prohibited residences with less than 500 cubic feet of air per person; the sidewalk ordinance, which made basket-carrying across the shoulder a misdemeanor; and the queue ordinance, which instructed that hair of prisoners be cut within an inch of scalp, aimed at humiliating Chinese men who, for spiritual reasons, wore their hair in a type of a topknot.

Around this time, Ah Toy began getting called into court, not as a plaintiff, but as a defendant. In 1851, seven hundred “native-born Protestant men” formed the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance to dispense justice outside the government, especially regarding prostitution and other vices, which had previously been unregulated. The vigilance committee was a curious thing, even by the standards of the time. “To law-loving, peaceable, worthy people in the Atlantic States and Europe, it did certainly seem surprising, that a city really of thirty thousand inhabitants… should patiently submit to the improvised law and arbitrary will of a secret society among themselves, however numerous, honest and respectable the members might be reputed,” declared The Annals of San Francisco, a historical document from the time.

The vigilance committee set itself “above all formal law” and “openly administered summary justice, or what they called justice, in armed opposition and defiance to the regularly constituted tribunals of the country,” according to The Annals. Although the committee had no official authority, it received “almost unanimous” support from the respectable San Francisco community, and functioned as a de facto power.

John A. Clark, a surveyor and the son of a former mayor of New York City, was named special patrol of the committee and charged with investigating brothels, with the eventual goal of deporting Ah Toy, who was among the most visible of San Francisco’s prostitutes. But instead of deporting her, he was wooed by her. In return for her affection, he would provide her protection, or so went the implicit contract.

Before long, though, Clark took to beating her. The following year, in 1852, Ah Toy took him to court. She told the presiding judge, Edward McGowan, that Clark had beaten her for telling someone she was his mistress. Judge McGowan dismissed the lawsuit as a personal matter.

In 1854, Ah Toy tried taking Clark to court again for domestic violence, which is when she learned that California had passed a law that year barring nonwhites from testifying in court. Other laws, equally discriminatory, had also been passed, denying basic civil rights to the Chinese community, including the right to be employed in public works, to intermarry, and to own land. All these strictures had existed informally before; now they were enshrined in law.

Also that year, the Common Council, a legislative body that was a predecessor of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, passed an ordinance banning brothels in general—though in practice, it was most strictly enforced against Mexican and Chinese brothels, many of which closed. White brothels, which served the same social function, but were sometimes owned by social elites such as William Ralston, who later founded the Bank of California, were protected from censure.

Eventually, Ah Toy herself was arrested, convicted, and fined for “disorderly housekeeping,” legislation that exists today in the form of pandering laws, which punish those who aid in acts of prostitution. Three years later, in 1857, she left for China, telling reporters that she was leaving for good. She soon returned, however, and was arrested yet again, in March 1859.

*

1860 marked the beginning of their industry’s decline, for Ah Toy and others like her. By then, enough women had immigrated from China to balance out the skewed gender ratio in California, and the demand for prostitutes subsided. (According to Ronald Takaki’s 1989 book Strangers from a Different Shore, in 1852 there were about eleven thousand Chinese in California, only seven of whom were women, but by 1880, there were around three thousand Chinese women in the state.) Politicians began to criticize Chinese prostitution not only as a threat to the “health of white men,” but also in economic terms, because they took away “sewing and other jobs from white women,” according to UCLA sociology professor Lucie Cheng Hirata in her 1979 article “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in Nineteenth-Century America.”

In 1865, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed an “Order to Remove Chinese Women of Ill-Fame from Certain Limits in the City.” The next year, the California state legislature approved an “Act for the Suppression of Chinese Houses of Ill-Fame.” Between 1866 and 1905, eight codes were passed in California targeting Chinese prostitutes and their brothels. Women who were caught would be fined twenty-five to fifty dollars (between $400 and $800 today), and jailed for five days. White prostitutes were exempt from such scrutiny.

What sealed the fate of Chinese prostitutes in San Francisco was the arrival of large numbers of white Victorian women, who started families and formed missionary circles. Margaret Culbertson and Donaldina Cameron were two such who took it upon themselves to “rescue” Chinese women, including those who had been sold into the sex trade against their will, but also those who were working freely as prostitutes. Culbertson is said to have “rescued” three thousand Chinese women, whom she kept in a boarding house and worked toward rehabilitating as she saw fit, while Cameron sent former prostitutes to work in the fields for Northern Californian fruit growers, with whom she had a standing agreement to supply labor. The missionary women, who were ideologically allied with the rising Temperance movement at the time, saw prostitution not as a “necessary evil to be tolerated” but a “social evil to be eradicated,” Barbara Berglund wrote in Making San Francisco American (2007).

“Many white women, perhaps including Cameron herself, were motivated by a sense of moral superiority,” according to Hirata. “The more they saw Chinese women as helpless, weak, depraved, and victimized, the more aroused was their missionary zeal. Saving the Chinese slave girls seemed to have become the ‘white woman’s burden.’” And once Chinese women were cast as victims in need of saving, there was no going back.

At this point, the codification of racist and sexist measures reached not only local and state, but also federal, levels. The first federal anti-prostitution legislation to pass was the 1870 “Act to Prevent the Kidnapping and Importation of Mongolian, Chinese, and Japanese Females for Criminal or Demoralizing Purposes,” which made it illegal to bring any Asian women to America unless there was proof that she was “of correct habits and good character,” according to the 1869–1870 Statutes of California. The enmity against Chinese communities would continue to grow, inflamed by the economic depression that set in following the Civil War and by the Panic of 1873. Chinese laborers were blamed for taking jobs from white Americans.

Then, in 1875, building on the 1870 Act, the Page Act was passed, which aimed to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” The Page Act purported to identify women of questionable character and bar their immigration, but it effectively discouraged immigration of all Chinese women. In Hong Kong, the self-appointed chief enforcer of the act, Consul David Bailey, began charging prospective Chinese immigrants an additional ten to fifteen dollars as graft, before posing such questions as, “Are you a virtuous woman?” The number of Chinese women entering the United States between 1876 and 1882 declined by 68 percent from previous years. By effectively barring Chinese women from entering the United States, the Page Act limited opportunities for Chinese men to bring over their families or start new ones, paradoxically encouraging the very vice—prostitution—it was meant to suppress.

The few Chinese women who did manage to immigrate in the late 1870s and early 1880s found a country that simultaneously placed them a rung below white women socially, while sexualizing them as exotic Orientals. Some, like Ah Toy, capitalized on this; others suffered in silence. Free, sexually liberated women have always been a cause for social anxiety, while the unconventional marital norms of the Chinese—the practice of keeping concubines, for example—were seen as a threat to so-called American values. (As for Chinese miners, all of whom were male, the limitations placed on the immigration of Chinese women meant the men could not form families, and were forced to remain as migrant laborers, untethered to any community, just where their employers wanted them.)

By the time the Page Act was introduced, the legendary Ah Toy had receded from public view. She had retired from prostitution and moved to San Jose in 1868, and three years later, in 1871, married a man named One Ho. Relatively little is known about her later years: reportedly, her husband died in 1909, and thereafter, she took to selling clams. She died in San Jose in 1928, three months before her hundredth birthday.

*

The Page Act, as it turned out, was only a precursor to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first US legislation to penalize a group of people based on race and formalize the concept of illegal immigration in America. The Act banned Chinese from coming to America and restricted the lives of those who were already here by requiring Chinese residents to seek permission for reentry if they left the country, barring them from obtaining citizenship, and making it impossible for family to come and visit. It was repealed only in 1943, and only because Beijing became a US ally in its fight against Japan. At last, Chinese people were allowed to become naturalized citizens, marry whites, own land, and live outside of Chinatowns.

Yet, to this day, we have abundant evidence that racism against Asians exists in this country. The surge of xenophobic abuse and hate crimes that has accompanied the coronavirus pandemic show all too clearly how this ugly history persists. Ah Toy’s story highlights the ways in which American racism and sexism are as old as the country. While Ah Toy worked as a prostitute and madam, customs officials, scamming customers, vigilante men, white brothel owners, and white Christian missionary women persistently tried to yank away her freedom. She refused to let them. In her refusal, we sense a revolutionary spirit that saw America clearly for what it was: a country that legislates oppression, where rights and freedoms must be fought for unendingly.